CHAPTER 16 Introduction to inflammatory conditions of the small and large bowel

Introduction

Inflammatory disorders account for a significant proportion of bowel related disease. The two main inflammatory conditions – ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, which are collectively referred to as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – affect up to 1 in 200 of the European and North American population between them (Kappelman et al., 2007). There are also a number of other inflammatory conditions that can affect the bowel, usually as part of wider systemic disease involving other organs, but these occur much less commonly (Table 16.1). This chapter will therefore largely focus on inflammatory bowel disease, although brief reference will be given to some of these other conditions.

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Connective tissue disease with gut involvement |

|---|---|

| Ulcerative colitis | Behçet’s |

| Crohn’s disease | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Microscopic colitis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Systemic sclerosis | |

| Polyarteritis nodosum | |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | |

| Henoch-Schönlein | |

| Sarcoid |

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis, the slightly more common of the two conditions, causes inflammation of the colon, whereas Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth through to the anus. Both conditions tend to follow a chronic relapsing and remitting course and can lead to disabling symptoms and complications.

Studies have shown similar rates of IBD in Europe and North America where the estimated incidence of ulcerative colitis ranges from 8.8 to 13.4 new cases per 100 000 population per year, with slightly lower rates for Crohn’s disease of 5.6 to 8.6/100 000/year. The incidence of Crohn’s disease appears to be increasing, while that of ulcerative colitis is stable (Loftus et al., 2007). Rates of IBD in Africa and Asia are thought to be much lower, although limitations in case definition may have led to some underestimation. All age groups can be affected, although the condition is unusual in infancy, with the peak age of diagnosis occurring between the ages of 15 and 30 years, with a second peak between the ages of 50 and 80. Women and men are affected equally (Gunesh et al., 2008).

Genetic factors

It has been known for a long time that first degree relatives of patients with IBD are between 3 and 20 times more likely to develop IBD themselves and that the risk for twins with IBD was much higher (Thompson et al., 1996). A number of genes have now been identified to explain this observation and a complex picture is emerging with at least 30 different genes involved (Barrett et al., 2008). It seems likely that certain genes confer susceptibility to specific patterns of IBD, which becomes activated if other trigger factors arise. The best example and the gene about which most is known is the IBD1 or NOD2 gene, present on chromosome 16. Mutations of this gene have been shown to be associated with increased rates of Crohn’s disease involving the ileum. The gene itself codes for a protein that is involved in the interaction between the gut’s immune system and gut bacteria and it seems likely that Crohn’s disease can be triggered in an IBD1 individual who comes into contact with certain bacteria that they are unable to deal with effectively. Unfortunately, at the moment, the bacteria or group of bacteria involved have not been identified (Hisamatsu et al., 2003).

Environmental factors

The strongest evidence for an environmental trigger relates to cigarette smoking, which has intriguingly been shown to confer a risk of developing Crohn’s disease, while protecting individuals from ulcerative colitis. The mechanism of this effect has not been identified, but it is also recognized that Crohn’s disease can be more aggressive in smokers compared with non-smokers, whereas the converse is true in ulcerative colitis (Mahid et al., 2006).

Other environmental factors that have been suggested include the oral contraceptive pill and various dietary factors such as food additives, processed fats and refined sugars, although the evidence for most of these is limited (Reif et al., 1997).

Microbial factors

As with environmental factors, most of the early work in this field focused on trying to identify ‘the’ infective cause of IBD. Potential candidates included Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, which is known to cause a Crohn’s-like illness in cattle called Johne’s disease. However, this has always been controversial and, to date, no clear cause has been identified, despite large amounts of research, although it remains possible that M. paratuberculosis may play some part in the IBD story (Freeman and Noble, 2005). Other equally controversial studies have focused on the measles virus and the potential link between measles vaccine and Crohn’s disease (Thompson et al., 1995) but, once again, this association has not been confirmed. Consequently, recent research has tended to move away from looking at specific organisms and has focused on the interaction between the gut and the microflora of bacteria it contains. This shows potential as an area for research, although, like the field of genetics, the area is hugely complex; for example, it has now been shown that IBD patients are more likely to have received antibiotics in childhood (Hildebrand et al., 2008), which is just one of the many factors that could have an impact on gut flora.

Signs and symptoms

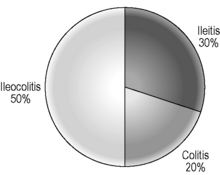

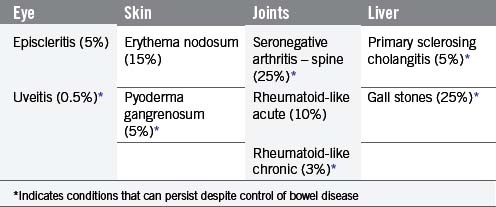

The signs and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease largely depend on the site affected and the nature of bowel involvement at the site. Consequently, the symptoms of ulcerative colitis, which only involves the colon, are more predictable than those of Crohn’s disease, which can occur anywhere within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Figure 16.1). However, a number of patterns can be recognized. In addition, both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease can be associated with a number of symptoms that occur outside of the GI tract (Table 16.2), particularly when the disease involves the colon (Orchard, 2003).

Ulcerative colitis

The relapsing and remitting nature of UC means patients experience symptoms at times when the disease is active, commonly referred to as a flare, interspersed by periods without symptoms. Symptoms tend to build up gradually and often last for several weeks at a time. The severity of symptoms is at least in part explained by the extent of colon affected. The rectum is inflamed in all patients, but the extent of proximal colonic inflammation varies, with approximately 30% of sufferers having disease confined to the rectum, 40% with disease of the left colon and 30% developing total colonic inflammation (Jess et al., 2006). Individuals tend to follow the same pattern with each flare leading to inflammation in the same part of the colon, with only around 15% of patients experiencing extent progression over time.

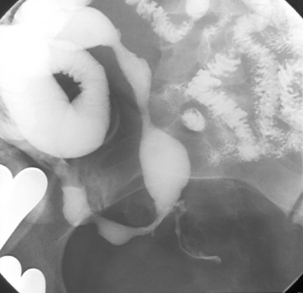

Most patients with proctitis and left-sided colitis present with relatively mild or moderate symptoms with little or no systemic upset and are managed as outpatients, whereas patients with pan colonic involvement (Figure 16.2) often have a more aggressive presentation with malaise, anemia, fever, tachycardia and abdominal pain. A proportion of patients presenting with severe disease will fail to settle despite treatment and, in the past, this type of presentation was associated with significant mortality. However, this is now largely avoided by ensuring that patients who fail to settle have surgery to remove the inflamed colon (colectomy) before complications such as bowel perforation develop. Factors that help predict patients at risk of not settling have been developed and most centers find that about 20–30% of patients presenting acutely with severe symptoms will require colectomy (Travis et al., 1996).

Crohn’s disease

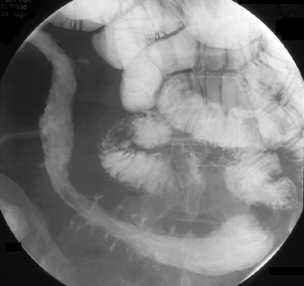

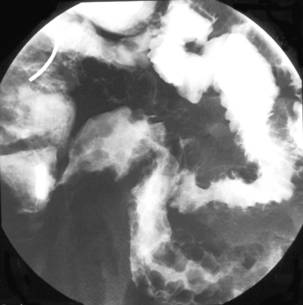

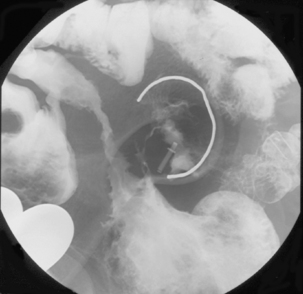

Like ulcerative colitis, the symptoms of Crohn’s disease tend to reflect the site of affected bowel and, as Crohn’s disease can occur anywhere within the GI tract, there is a wider variety of presentations than in UC. The inflammation in Crohn’s disease involves the full thickness of the bowel wall (Figures 16.3 and 16.4) and, consequently, healing with fibrosis leading to scar tissue and narrowing of the bowel or ‘stricturing’ is common (Figure 16.5). Holes in the bowel wall can also develop and these often lead to communication between the bowel and skin or other abdominal structures, known as fistulae (Figure 16.6). Over time, it is estimated that between 30 and 50% of Crohn’s patients will develop fistula, with the majority involving communication between the bowel and the peri-anal skin (Schwartz et al., 2002). General systemic features, such as lethargy and abdominal pain, are also more common in Crohn’s disease.

Colonic Crohn’s disease

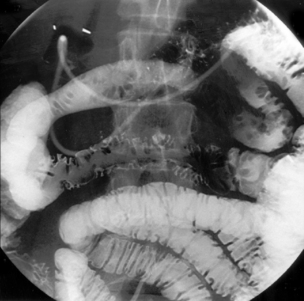

Approximately 20% of Crohn’s patients have disease that is limited to the colon (Figure 16.7). Symptoms tend to be similar to those in ulcerative colitis, although, unlike in UC, the rectum is not always involved – so bleeding is less common.

Ileo-colonic Crohn’s disease

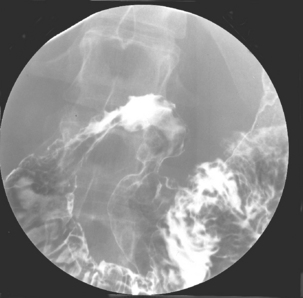

This is the commonest pattern of Crohn’s disease occurring in around 50% of patients. Inflammation involves both the colon and the small bowel, most commonly in the region of the terminal ileum. Symptoms reflect a mixture of colonic related bowel upset combined with symptoms from the small bowel involvement such as abdominal pain and excessively noisy bowel activity (borborygmi). Small bowel strictures commonly occur (Figure 16.8), leading to intermittent episodes of bowel obstruction, characterized by severe colicky abdominal pain, bloating and borborygmi, which classically come on within an hour of eating. Patients with more extensive small bowel involvement will often experience marked weight loss due to a combination of disease activity and reduced absorption of nutrients.

Isolated ileitis or small bowel involvement

This pattern accounts for about 30% of Crohn’s disease. Symptoms can be similar to those experienced by patients with ileo-colonic disease, although diarrhea may be less marked and even absent in some cases. Weight loss and systemic features may predominate.

Peri-anal disease

This can occur in isolation, or in association with any of the other patterns of disease distribution described, although it is more common in patients with colonic involvement. Potential presentations include anal fissure, peri-anal fistula, peri-anal abscess and inflammatory skin tags. Anal fissure involves a small break or inflamed area within the anal margin, which results in extreme pain on defecation. Rectal examination is usually impossible due to pain and resultant spasm of the anal sphincter muscles. Peri-anal fistulae are very common and lead to discharge of bowel content through tracts onto the peri-anal skin. These frequently become infected and lead to peri-anal abscess formation, involving the build up of infected material under the peri-anal skin leading to painful subcutaneous swelling and systemic symptoms of infection.

Upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease

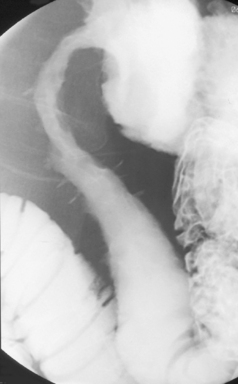

Crohn’s disease involving the esophagus, stomach or duodenum is relatively uncommon and collectively occurs in only 5% or so of patients (Figure 16.9). Symptoms that raise the possibility of upper GI involvement include dysphagia or painful swallowing (odynophagia), ulcer-like epigastric pain and pain occurring immediately or very soon after eating. This form of disease can be difficult to treat and warrants aggressive therapy.

Pathophysiology

Both forms of inflammatory bowel disease are characterized by chronic inflammation of the bowel and, while the exact etiology of the conditions remains unknown (see above), the pathological consequences of the disease are well documented.

The pathological hallmark of Crohn’s disease is full thickness inflammation of the intestine, with associated granuloma formation. Involvement is often patchy with normal areas of intestine interspersed between areas of inflammation. This contrasts with ulcerative colitis where the inflammation is more superficial and always continuous, starting at the rectum and extending proximally to the limit of the disease. Macroscopically, both conditions manifest themselves through ulceration of the bowel mucosa with related mucosal swelling (edema) and loss of the normal appearance of bowel features. The ulcers in Crohn’s disease are typically deeper and more defined than those seen in ulcerative colitis, although there is considerable overlap and, where Crohn’s disease does present as confluent inflammation in the colon, the two conditions can be difficult to distinguish (Williams et al., 2003).

Diagnosis and management

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease relies on a high index of clinical suspicion based on the symptoms, coupled with appropriate investigation to confirm the presence of the characteristic pathological features (Carter et al., 2004). Despite our increased understanding about inflammatory bowel disease, patients still often experience a delay before being diagnosed; for example, a study from the USA found that the average time from symptom onset to diagnosis was over 7 years for Crohn’s patients and just over a year for ulcerative colitis (Pimentel et al., 2000). This most likely reflects the rather non-specific nature and gradual onset of symptoms in some patients with Crohn’s disease and serves as a reminder that clinical vigilance is necessary to make the diagnosis.

Crohn’s disease involving the more proximal small bowel is less accessible to endoscopic diagnosis and diagnosis has tended to rely on demonstration of typical features of small bowel Crohn’s using radiological techniques. This has the limitation of not obtaining tissue for histological analysis, but a combination of typical features in a patient with symptoms suggestive of the diagnosis is usually reliable. The imaging of the small bowel is considered in more detail in earlier chapters and it seems likely that there will be an increasing trend towards using magnetic resonance imaging in this setting (Masselli et al., 2008), although emerging endoscopic tests such as wireless capsule endoscopy and balloon assisted enteroscopy may play a complementary role (Chong et al., 2005).

Management

The treatment of inflammatory bowel disease is complex and, for many patients, involves a combination of medical therapy to control the inflammatory process, emotional support to assist with the impact for the patient from their chronic disease, nutritional support and surgical treatment for resistant disease or where complications such as strictures or abscess develop. Treatment decisions depend on clear identification of the nature and extent of the bowel that is affected (Carter et al., 2004).

Crohn’s disease

Like ulcerative colitis, treatment of Crohn’s disease is dictated by the disease severity and site of bowel involved. Colonic Crohn’s disease is treated similarly to ulcerative colitis, although mesalazine treatment tends to be less effective and, consequently, more patients will end up on immunosuppressive therapy. Small bowel disease usually requires immunosuppressive therapy to control inflammation. Steroids are commonly used in the short term, but have limited efficacy in the long term due to side effects. Conventional immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine and methotrexate, can be highly effective but, like steroids, can be limited by side effects. They also have a delayed onset of action, meaning that other drugs are often needed to bridge the time period until they become effective. Infliximab and Adalumimab are two relatively new drugs that were developed specifically to block tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which is one of the many chemicals (cytokines) involved in triggering and sustaining the inflammatory process in Crohn’s disease. Results have been encouraging with response in up to 70% of patients treated (Figure 16.10) and the use of these drugs is steadily increasing, despite treatment costs averaging around £10 000 per year. However, some concern remains about their long-term effectiveness and safety profile (Peyrin-Biroulet et al., 2008).

Despite the advances in medical therapy for Crohn’s disease, surgery is still required by up to 50% of Crohn’s patients within the first 10 years after diagnosis and, for many patients, close liaison between surgeon and physician is required to enable optimal management (Fichera and Michelassi, 2007). Common surgical procedures in Crohn’s disease include drainage of abscesses with correction of fistula and resection of segments of strictured bowel (Figure 16.11). Carefully planned and expertly performed surgery is essential to minimize loss of bowel, as patients frequently require several operations over their lifetime and the impact of cumulative bowel loss remains a concern for some patients.

Differential diagnoses

The conditions that need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease are largely dictated by the type of symptoms involved and can usually be distinguished based on the clinical history and results of initial investigation. Table 16.3 provides a reference to some of the common conditions that can mimic certain presentations of inflammatory bowel disease.

| IBD symptoms | Common conditions included in differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Acute bloody diarrhea (UC or Crohn’s) | Infective enteritis, e.g. Campylobacter |

| Diverticular disease | |

| Ischemic colitis | |

| Colon cancer | |

| NSAID-induced colitis | |

| Chronic diarrhea (Crohn’s or UC) | Giardia |

| Celiac disease | |

| Bile salt malabsorption | |

| Bacterial overgrowth | |

| Microscopic colitis | |

| Lactose intolerance | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Severe abdominal pain (Crohn’s) | Any cause of an acute abdomen, e.g. appendicitis |

| Chronic abdominal pain (Crohn’s) | Diverticular disease |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Abdominal malignancy | |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | |

| Endometriosis | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | |

| Biliary pathology | |

| Peptic ulceration | |

| Connective tissue disease of gut | |

| Adhesions | |

| Malabsorption/weight loss | Celiac disease |

| Jejunal diverticula | |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | |

| Anorexia | |

| Addison’s disease | |

| Abdominal tuberculosis |

NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Prognosis

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis tends to follow a relapsing and remitting course over time, with about 50% of patients in full remission at any time. Once a patient achieves remission following an attack they have about a 70% chance of having a further flare during the next year. This risk can be reduced but not avoided by use of maintenance therapy. For all patients, the risk of having a colectomy within the first 10 years of diagnosis is in the region of 25%, although this is likely to be lower for patients with limited or left-sided disease (Langholz et al., 1994). The prognosis following a severe attack of colitis has been discussed previously but, with modern treatment, the risk of death should not exceed 1%. Overall life expectancy is thought not to be reduced, but there is a clearly documented increased risk of developing bowel cancer among UC patients, with a likelihood of developing bowel cancer in the region of 5–10% after 20 years. This risk seems to be focused on patients with extensive disease of the colon and it is conventional to offer such patients regular surveillance.

Crohn’s disease

Like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease also follows a relapsing and remitting course over time but, unlike UC, the natural history tends to involve the gradual development of complications such as strictures and fistulae. These in turn lead to the need for surgical correction, with around 50% of patients requiring surgery within 10 years from diagnosis (Solberg et al., 2007). In contrast to UC, surgery is not curative and the disease frequently recurs with about 50% of patients requiring a further operation within 10 years of their first procedure. A proportion of patients have disease that appears to follow an aggressive course, characterized by frequent relapse and rapid development of complications. In the past, these patients were at risk of developing intestinal failure over time but, fortunately, aggressive modern management of Crohn’s disease appears to be reducing this rate. However, most studies still show that average life expectancy is slightly reduced among patients with Crohn’s disease.

Barrett J.C., Hansoul S., Nicolae D.L., et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat. Genet.. 2008;40(8):955-962.

Carter M.J., Lobo A.J., Travis S.P.L. British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl. V):v1-v16.

Chong A.K., Taylor A., Miller A., et al. Capsule endoscopy vs. push enteroscopy and enteroclysis in suspected small-bowel Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest. Endosc.. 2005;61(2):255-261.

Fichera A., Michelassi F. Surgical treatment of Crohn’s disease. J. Gastrointest. Surg.. 2007;11(6):791-803.

Freeman H., Noble M. Lack of evidence for Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in Crohn’s disease regulation of immunity. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.. 2005;11(8):782.

Gunesh S., Thomas G.A.O., Williams G.T., et al. The incidence of Crohn’s disease in Cardiff over the last 75 years: an update for 1996–2005. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.. 2008;27(3):211-219.

Hildebrand H., Malmborg P., Askling J., et al. Early-life exposures associated with antibiotic use and risk of subsequent Crohn’s disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol.. 2008;43(8):961-966.

Hisamatsu T., Suzuki M., Reinecker H.C., et al. CARD15/NOD2 functions as an antibacterial factor in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(4):993-1000.

Jess T., Riis L., Vind A., et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.. 2006;13:481-489.

Kappelman M.D., Rifas- Shiman S.L., Kleinman K., et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2007;5:1424.

Langholz E., Munkholm P., Davidsen M., et al. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(1):3-11.

Loftus C.G., Loftus E.V.Jr, Harmsen W.S., et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.. 2007;13(3):254-261.

Mahid S.S., Minor K.S., Soto R.E., et al. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc.. 2006;81:1462-1471.

Masselli G., Casciani E., Polettini E., et al. Comparison of MR enteroclysis with MR enterography and conventional enteroclysis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Eur. Radiol.. 2008;18(3):438-447.

Orchard T. Extraintestinal complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep.. 2003;5(6):512-517.

Peyrin-Biroulet L., Deltenre P., De Suray N., et al. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn’s disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2008;6:644-653.

Pimentel M., Chang M., Chow E.J., et al. Identification of a prodromal period in Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol.. 2000;95(12):3458-3462.

Reif S., Klein I., Lubin F., et al. Pre-illness dietary factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1997;40(6):754-760.

Schwartz D.A., Loftus E.V.Jr., Tremaine W.J., et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):875-880.

Solberg I.C., Vatn M.H., Hoie O., et al. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2007;5(12):1430-1438.

Thompson N.P., Driscoll R., Pounder R.E., et al. Genetics versus environment in inflammatory bowel disease: results of a British twin study. Br. Med. J.. 1996;312:95-96.

Thompson N.P., Montgomery S.M., Pounder R.E., Wakefield A.J. Is measles vaccination a risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease? Lancet. 1995;345(8957):1071-1074.

Travis S.P.L., Farrant J.M., Ricketts C. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:905-910.

Williams G., Sloan J., Warren B., et al. Morson and Dawson’s gastrointestinal pathology, fourth ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.