Chapter 1 Introduction, summary, the system of care

Introduction

In the UK and in other countries there is a growing shortage of trained clinicians to meet the need for immediate assessment and treatment of urgent medical problems in primary care. Traditionally doctors have been the main providers of this care but already nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals are extending their role to include clinical assessment, decision making, and treatment.1,2 Our aim is that this book will be a useful update for general practitioners experienced in this field and also serve as an introduction to those new to emergency clinical decision making.

Lastly and perhaps most importantly, the book sets the immediate management in the context of the start of the patient’s journey. The key principle (Box 1.1) is – what is right for this patient, in this setting, with my skills, at this time? There is evidence that some pre-hospital interventions may make patient outcomes worse. Just because a particular line of management can be practiced out of hospital it does not necessarily mean that it should be done.

Box 1.1 Key points

Scope

The book outline is given in Box 1.2. This encompasses most of acute emergency medicine. Trauma is occasionally mentioned as it can be part of the presenting complaint (for example, in a collapse with an injury) or a possible cause (for example, in chest pain). However we will not deal with serious trauma as this is well covered in other texts.

The three step system of care

Overview

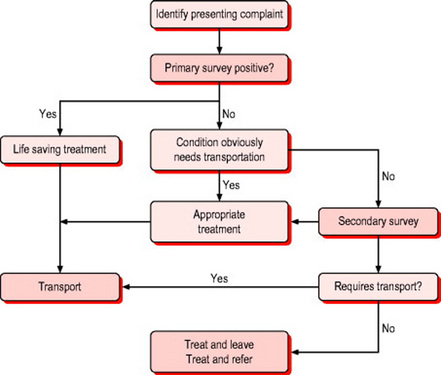

We will use a three step system of care (Box 1.3). The first step is to identify those patients with immediately life threatening problems, the second is to identify those patients who will need to go to hospital, and the third to fully assess that majority of patients encountered in community emergency care that will not require hospital referral. There may be no single ‘right answer’ to the immediate management of each of these problems. The variables in levels of training, distance or time to definitive care will influence the decision on the right management for this patient at this time and in this place (see below).

Box 1.3 The system of care

Step 1 – identify those patients with immediately life threatening problems, provide essential initial resuscitation and transport

Step 1 – identify those patients with immediately life threatening problems, provide essential initial resuscitation and transportStep 1

The first step is to identify those patients who are ‘primary survey positive’. This process will usually take less than 30 seconds. If the patient is talking in full sentences, is fully orientated, the respiratory rate is between 10 and 29 breaths per minute, the pulse rate between 50 and 120, and the patient is not cold and sweating, then it is unlikely they need immediate resuscitation (Box 1.4).

Step 2

The next step is to identify the patient who obviously needs hospital admission, especially if the treatment needs to be given as soon as possible to reduce risk to life or limb (Box 1.5). Examples would be acute myocardial infarction, bleeding, suspected aortic aneurysm or imminent childbirth. In these patients essential treatment should be provided and transport to the appropriate hospital arranged.

Primary survey positive

Which treatment does the patient need now?

There are some conditions that demand immediate treatment. For example, the outcomes of cardiac arrest are dependent on the time to defibrillation; anaphylaxis needs epinephrine, and an obstructed airway requires urgent attention. However, in many other conditions the evidence is not so clear. The principle should be to do the minimum necessary while preparing for transport and to continue treatment en route. Life threatening asthma would be a good example. Starting an oxygen-driven salbutamol nebuliser and ensuring there were no signs of a tension pneumothorax would be the main on scene interventions. Rapid transport to hospital would be the next priority with en route treatment and evaluation as necessary.

Patient obviously requires hospital treatment

Many patients will have conditions requiring hospital care. Box 1.6 lists some that need emergency transfer. However, the patient with a fracture neck of femur requires a brief history, vital signs, pain relief and written notes including a treatment plan. This allows their care in hospital to be a continuum rather than simply repetition of the pre-hospital assessment.

Secondary survey

Patient stable, no immediate reason for hospital transport

The decision to assess, treat, and leave requires much more care and judgement than the decision to transfer to hospital. It also carries higher risk. Equally the whole system would be swamped if all patients were sent to hospital. In some presenting complaints, for example chest pain, a high proportion of patients will require hospital evaluation. Other complaints such as a sore throat will rarely need anything other than advice or simple treatment. To minimise the risk it is essential that clinicians carry out a systematic assessment. We outline one such system – SOAPC3 (Box 1.7). There are many others. It is not important which you use, as long as you use a system that includes all the key elements.

Subjective information gathering: the history

Where there is a definite pathology, a full understanding of the history of the patient’s problem will give very clear pointers to the diagnosis in the majority of cases.4 Examination and tests may help confirm the provisional diagnosis but the history remains the key tool of the emergency care clinician.

The process of history taking can be conveniently broken down into the components shown in Box 1.8. Elicit and record the patient’s chief complaint. This will often direct the clinician down a particular line of thought or specific care pathway. However, always be willing to change direction as other evidence is obtained. It is very common for presenting complaints to change over time as a disease develops. The initial symptoms of influenza, meningitis and pneumonia may be identical, making the diagnosis difficult or impossible. Within 6 hours the patient may have developed the rash, photophobia and neck stiffness or the pleuritic chest pain, breathlessness and green sputum that would allow a layman to make the diagnosis. The initial consultation assesses the patient at one point in the disease process, the emergency care clinician can return to re-assess the patient’s progress.

Box 1.8 Key parts of the history

Objective information gathering

Examination

Vital signs (temperature, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation) are often the first and most important indicator of the severity of a patient’s illness. They provide an objective measure of the patient’s physiology at the time of the examination. As noted in Box 1.3 vital signs are key in spotting those patients who are primary survey positive. Vital signs may be normal in many life threatening situations (acute MI is the obvious example) – a patient’s condition can change rapidly. Fail to record vital signs, or to take heed of abnormal readings, at your peril.

General examination focuses on the systemic signs of disease. Identifying the unwell patient is one of the key skills for any emergency clinician. It is hard to describe the grey, anxious, and slightly dehydrated appearance of the patient with serious illness but clues are to be observed in the general demeanour, the face and eyes, the tongue, skin colour, and turgor (Box 1.9).

Complaint specific examination concentrates on the system(s) indicated by the history. There are many books on physical examination and Chapter 2 provides a reasonable standard for community emergency care. Develop a system of examination such as ‘look, feel, listen’ or ‘look, feel, move’ appropriate to the part of the body being examined.

Tests

There are few investigations currently available in the community emergency care setting. The most common are listed in Box 1.10. The 12-lead electrocardiograph (ECG) is perhaps the most useful. Do not place too much reliance on a single test. For example, in acute chest pain the initial ECG will be normal in 50% of patients who are having an acute myocardial infarct.5 If someone has a very typical history of ischaemic chest pain then there is a very high clinical suspicion (high pre-test probability) of ischaemic heart disease. In such cases a normal ECG would not influence the referral to hospital. Investigations are probably more important in patients who are going to be left at home. The types and scope of such investigations is likely to increase in the future.

Plan – treatment and ongoing care

Treat and refer

Such patients have a problem that does not need hospital treatment but do require further assessment or treatment. Common examples are the older patient with social care needs or patients requiring community nursing support. Each health system will need to develop a range of clearly defined pathways for referral. Again documentation and a clear treatment plan are essential.

The variables in community emergency care

The patient

From the newborn child to the 100-year-old woman, from the fit young man having a cardiac arrest playing sport to the dangerously overweight patient on multiple medications, the community emergency care practitioner has to deal with all situations as they present. There is no immediate access to paediatricians, surgeons or the intensive care specialist. The community emergency care practitioner has only their own skills and judgement and training. Increasingly they may be able to use telemedicine or even the humble telephone for a second opinion but they are the clinicians on the spot. Judgement is required to consider how an individual with all their previous history and current circumstances will fit into a specific care pathway (Box 1.11).

Summary

Community emergency care represents a highly complex situation in which a very wide variety of conditions are managed by different types of practitioners with a range of competences. A systematic approach to assessment and management is therefore essential to ensure patients are receiving the correct care, in the correct place, at the correct time. This book describes one such systematic approach.

1 Mason S, Wardrope J, Perrin J. Developing the community paramedic practitioner intermediate care support scheme for older people with minor conditions. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:196-198.

2 Pedley D, Bisset K, Connolly EM, et al. Prospective observational study of time saved by pre hospital thrombolysis for ST elevation myocardial infarction delivered by paramedics. BMJ. 2003;327:22-26.

3 Palmer KT. Notes for the MRCGP, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1998.

4 Hampton JR, Harrison MJB, Mitchell JRA. Relative contributions of history taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigations for diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. BMJ. 1975;2:486-489.

5 Morris F, Brody WJ. ABC of clinical electrocardiography. Acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 2002;324:831-834.