Introduction and classification

Definition

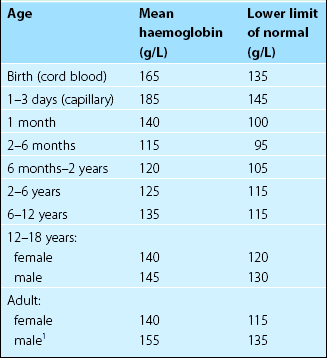

The normal range for haemoglobin concentration varies in men and women and in different age groups (Table 11.1). The definition of normality requires accurate haemoglobin estimation in a carefully selected reference population. Subjects with iron deficiency (up to 30% in some unselected populations) and pregnant women must be excluded or the lower level of normality will be misleadingly low. Normal haemoglobin ranges may vary between ethnic groups and between populations living at different altitudes.

Classification

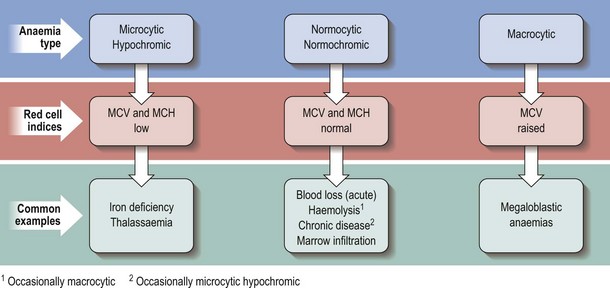

Anaemias with raised, normal and reduced red cell size (MCV) are termed macrocytic, normocytic and microcytic, respectively. Anaemias associated with a reduced haemoglobin concentration within red cells are termed hypochromic and those with a normal MCH are termed normochromic. Characteristic combinations are of microcytosis and hypochromia, and normocytosis and normochromia. As can be seen in Figure 11.1, this terminology is helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis of anaemia. It is perhaps least helpful in normocytic anaemia as the possible causes are numerous and diverse.

Aetiological classification

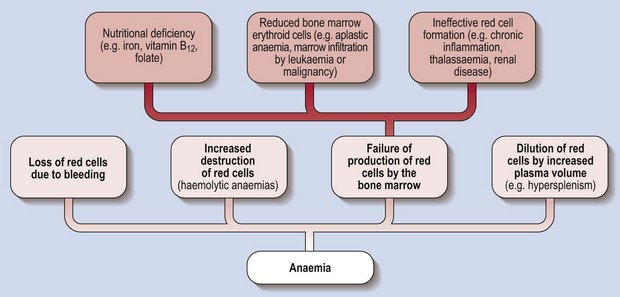

Figure 11.2 illustrates a classification of anaemia based on cause. It is less immediately helpful than the morphological classification in forming a differential diagnosis but it does illuminate the pathogenesis of anaemia. The fundamental division is between excessive loss or destruction of mature red cells, and inadequate production of red cells by the marrow.