Chapter 1. Introduction

History and development

Orthopaedic surgeons deal with deformity, diseases of bones and joints, and injuries to the musculoskeletal system. Because these are among the commonest things to affect humankind there must always have been orthopaedic surgeons of one kind or another, even in the most primitive communities. Wherever there was a witch doctor or medicine man dealing with illness and disease, as general practitioners and physicians do now, somewhere there would have been a ‘bone setter’ treating fractures and straightening limbs.

Despite these ancient origins, the word ‘orthopaedic’ is a recent introduction derived from the title of a book published by a French physician, Nicolas Andry, in 1741: Orthopaedia, or, The Art of Correcting and Preventing Deformities in Children: By such Means, as may easily be put in Practice by Parents themselves, and all such as are Employed in Educating Children.

The word itself is derived from the Greek orthos pais and means only ‘straight child’, but orthopaedic surgery has expanded from the correction of deformities in children to embrace every aspect of musculoskeletal surgery. Apart from coining the word orthopaedics, Andry also designed the symbol that has now become the worldwide logo of orthopaedic surgery. The ‘Tree of Andry’ is taken from an engraving in Orthopaedia that showed a crooked tree tied to a stake in order to straighten it (Fig. 1.1). The fact that it is virtually impossible to straighten a crooked limb by tying it to a straight splint has not affected the popularity of the symbol, which has been adapted for many purposes (Fig. 1.2).

|

| Fig. 1.1

The Tree of Andry.

By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London.

|

|

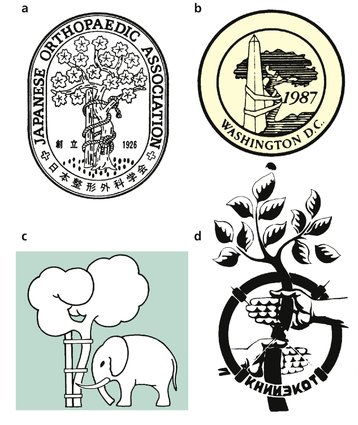

| Fig. 1.2

(a) The emblem of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. By kind permission of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. (b) The emblem of the Eighth Combined Meeting of the Orthopaedic Associations of the English Speaking World, Washington DC, 1987. By kind permission of the American Orthopaedic Association. (c) Emblem of the Orthopaedic Department, Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen, by kind permission. (d) Emblem of the Kurgan Scientific Research Institute of Experimental and Clinical Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Kurgan, Russia. By kind permission of Professor G.A. Ilizarov and the Pan Union Kurgan Scientific Centre for Reconstructive Traumatology and Orthopaedics.

|

In some countries, the work of the bone setter was willingly carried out by physicians, and Hippocrates himself is credited with the development of a technique for reducing dislocated shoulders which stood the test of time until general anaesthesia made it easy to overcome muscle spasm. Hippocrates is also said to have treated recurrent dislocation of the shoulder by applying a flaming torch to the axilla, but this treatment has not survived.

Physicians were not always as enlightened as Hippocrates. The bone setter, who earned his living by his ability to manipulate broken limbs, was often regarded with disfavour by the established medical profession, and this was certainly true in Britain. When the Medical Act of 1858 restricted the use of the title ‘Doctor’ to those who had passed certain recognized examinations, bone setters were excluded and became unregistered practitioners; however, this did not stop them practising, and their success remained a source of continual irritation to the medical profession. Orthopaedic hospitals existed in London and other large cities during the middle of the 19th century but they remained under the direction of registered medical practitioners.

The medical profession might have been denied access to the ‘black arts’ of the bone setters altogether if it had not been for Evan Thomas, renowned as the last of the great Welsh bone setters, who decided to put all five of his sons through medical school. One of these sons was the legendary Hugh Owen Thomas (1834–1891), who trained in Edinburgh but qualified with the London MRCS in 1857 (Fig. 1.3). It is ironic that when Hugh Owen Thomas joined his father’s practice in Liverpool, they found themselves unable to work together and quickly parted.

|

| Fig. 1.3

Hugh Owen Thomas.

By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London.

|

Hugh Owen Thomas had an enormous impact on the development of orthopaedic surgery in Britain, both by his own effort and through his influence upon his nephew Robert Jones (1857–1933). Between them, Hugh Owen Thomas and Robert Jones laid the foundations of British orthopaedic surgery so successfully that it is easy to forget that less than a century ago much of its present work was carried out by practitioners regarded as charlatans by the rest of the profession.

As orthopaedic surgery became established, it attracted much the same attention from factions within the medical profession as the profession had shown the bone setters of the previous century. In 1918, 12 surgeons founded the British Orthopaedic Association. Also in 1918, the Royal College of Surgeons in England found time in a busy schedule to ‘view with mistrust and disapprobation the movement in progress to remove the treatment of conditions, always properly regarded as the main portion of the General Surgeon’s work, from his hands and place it in those of “orthopaedic specialists”.’ The general surgeons were right to be worried; they are now almost outnumbered by orthopaedic surgeons and the gap is closing fast.

Orthopaedic surgery today

Modern orthopaedic surgery has changed radically since the time of Andry, and now extends from the neonate to the elderly. The following are some of the more important segments of orthopaedic surgery today.

Neonates

The orthopaedic surgeon takes care of congenital deformity. Prompt treatment of some conditions in the first few days of life can produce an almost perfect result, but treating the same condition later may be much more difficult (see ‘Developmental dysplasia of the hip’, p. 354).

Children

As in Andry’s time, children’s deformities are the province of the orthopaedic surgeon, but children’s orthopaedics now presents so many unusual and difficult problems that it has become a specialty in its own right (see Ch. 21).

Trauma

Trauma has always filled much of the surgeon’s time (Fig. 1.4). Today, multiple injuries, particularly road trauma, keep many beds full and form a large part of orthopaedic practice, sometimes to the exclusion of elective orthopaedic surgery.

|

| Fig. 1.4

Orthopaedic apparatus and instruments.

From Cooke J (1685) Mellificum Chirurgiae. By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London.

|

Sports medicine

In some countries sports medicine is a separate specialty but in the UK sports injuries fall within the scope of orthopaedics. Because the fitness of sportsmen and women attracts the interest of the public and the press, the orthopaedic surgeon can find this part of his or her work receiving special scrutiny.

Degenerative joint disease

Like trauma, degenerative joint disease occupies a great deal of orthopaedic attention. Total joint replacement, particularly of the hip and knee, is a hugely successful operation which relieves pain and restores mobility to patients who would otherwise be condemned to persistent pain and restricted movement for the rest of their lives.

The elderly

Finally, there are the disorders of old age. With increasing age, the bones become progressively more brittle until they fracture with negligible trauma. All too often, fracture of the neck of the femur in an old person living alone, with little family support, creates social problems that prove insuperable and mark the start of a downhill path that leads to death.

Involvement with other specialties

No modern doctor can practise ‘general’ medicine in isolation from colleagues, and this is particularly true for orthopaedic surgery. The orthopaedic surgeon must therefore have a working knowledge of many other disciplines.

Rheumatologists

Rheumatologists and orthopaedic surgeons deal with the same structures and must work closely together. A working knowledge of rheumatology is essential to the orthopaedic surgeon, just as a knowledge of orthopaedics is essential to the rheumatologist. In some countries the orthopaedic surgeon doubles as the rheumatologist.

Plastic surgeons

The management of trauma involves treating extensive skin loss: close liaison with the plastic surgeons is important for making the best use of available skin. If the initial management of a wound is bad, the work of the plastic surgeons is made more difficult. This is true of not only extensive skin loss but also the suturing of seemingly simple wounds in the accident department.

Neurologists

Apparently simple ‘orthopaedic’ problems, such as a recurrent sprain or weakness of an arm, may be the first indication of a neurological disorder such as a spinal tumour, muscular dystrophy or multiple sclerosis. To be able to detect the exceptional patient who has a neurological disorder and not a truly orthopaedic problem takes considerable experience.

General and thoracic surgeons

In the treatment of trauma, a good knowledge of the management of thoracic and abdominal injuries is mandatory. Much major trauma is first seen by the orthopaedic surgeon because of the damage to the limbs, and he or she must also assess the damage to the chest or abdomen (p. 167, p. 168, p. 169, p. 170, p. 171, p. 172, p. 173, p. 174, p. 175 and p. 176).

Community services

Community services are important to orthopaedic surgeons because they are closely involved with the health services outside hospital. An elderly lady with a fractured hip, for example, cannot be sent home to fend for herself without careful consultation with both the general practitioner and the community nurses (p. 75). The orthopaedic surgeon must also know how to arrange special educational facilities for children with physical handicap and how to arrange the rehabilitation of disabled patients.

What does orthopaedic surgery achieve?

The wide range of conditions and different types of patients makes orthopaedic surgery an unusually interesting specialty which offers ‘something for everybody’, but there is also the satisfaction of knowing that the majority of patients can be helped. Patients with disabling arthritis are made more comfortable, deformities can be corrected or prevented; few orthopaedic patients are ‘ill’ in the true sense of the word, and malignant disease is rare. Trauma patients, in particular, are usually healthy individuals plucked from the community at random, quite literally by accident, and restoring them to full fitness is very rewarding.

Orthopaedic operations

From a technical point of view, orthopaedic operations require a wide range of skills and techniques. Although many of the operations involve the traditional ‘wet carpentry’ of bone, using hammers, chisels and drills, techniques such as joint replacement demand a sound knowledge of mechanics and materials science. Orthopaedic surgery can also include the microsurgical repair of nerves and vessels, massive spinal surgery, intricate operations on the tendons of the hand, and endoscopy, all of which require different skills. This wide variety of techniques, involving instruments ranging from the operating microscope to the traditional hammer and chisel, demands a technical ability not required by surgeons in other specialties.