Chapter 1 Introduction

Clinicians have always performed the role of health care providers, where the family doctor has always been viewed as the logical interface with the community’s health needs. Integrative medicine (IM) is an established paradigm shift in medicine in areas such as the North American continent, India and China. Whereas in other areas of the world it is a developing movement, such as in continental Europe, especially Scandinavia, the Middle East and Australia. 1, 2

In a study of 23 153 German participants, aged 35 to 65 years, from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition–Potsdam study, found that adhering to just 4 lifestyle factors — namely, never smoking, having a body mass index less than 30, performing 3.5 hours/week or more of physical activity, and adhering to healthy dietary principles (high intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain bread and low meat consumption) — significantly reduces the risk of developing a chronic disease by up to 78%.5

Holistic health — caring for the whole person

The holistic model is traced back to the Hippocratic school of medicine (circa 400 BC) and the oath of Maimoides (circa the 12th century AD) which have fashioned and defined the unique obligations that clinicians have toward their patients and their medical practices. Disease and illness was viewed as an ‘effect’ from imbalance and explored causes of disease from the environment and natural phenomena such as air, water, and food. Early health practitioners used the term vis medicatrix naturae, meaning the healing power of nature, to describe the body’s ability to heal itself. Furthermore, the Hippocratic oath states: ‘first, do no harm’. It is important despite which style of medicine we use, whether it is a pharmaceutical agent, surgical approach or a natural therapy, that we do no harm to patients.

Holistic medicine also includes the integration of various safe, evidence-based complementary therapies and medicines that may provide a gentler, safer and, in some cases, more empowering approach to health care. Many medical and health practitioners worldwide are integrating various ethical non-pharmaceutical modalities into their clinical practice as part of the holistic approach. These forms of therapies aim to enhance a healthy lifestyle, work with the natural healing process, empower patients to be active participants in their own healing process and nurture the whole person. Where such therapies can be safely used, they include counselling, meditation and relaxation therapies, hypnosis, primary preventative medicine and lifestyle management, acupuncture, nutritional medicine, herbal medicine, environmental medicine, and physical and manipulative medicine. These therapies work in harmony with the natural healing processes of the body. Natural medicines, when used properly, generally are well tolerated and rarely cause side-effects. They generally support the body’s healing mechanisms, rather than take over the body’s processes.6

Integrative medicine

Integrative medicine (IM) refers to the blending of conventional and complementary medicines and therapies with the aim of using the most appropriate of either or both modalities to care for the patient as a whole.7

This closely reflects both the Hippocratic oath and the WHO definition discussed above. However, although some may view IM as synonymous with CAM, this was never so, nor was it ever the case. CAM comprises many therapeutic modalities that are not taught in a conventional medical syllabus, based on the ideas that range from those that are sensible and worth including in mainstream medicine to those that are extremely imprudent and a few that are very perilous. Neither the word alternative nor complementary captures the essence of IM.8 The former suggests a replacement of conventional therapies by others whereas the latter suggests therapies of varying value that may be used as adjuncts.

IM emphasises a number of issues including:9

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)

Complementary and alternative medicine, as defined by the National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), is a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine (see Table 1.1).10

| NCCAM classifies natural, complementary and alternative medicines into 5 categories, or domains | |

|---|---|

| 1 Alternative medical systems | Alternative medical systems are built upon complete systems of theory and practice such as homeopathic and naturopathic medicine, Traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. |

| 2 Mind–body interventions | These interventions include counselling, patient support groups, meditation, prayer, spiritual healing, and therapies that use creative outlets such as art, music, or dance. |

| 3 Biologically based therapies | These therapies include the use of herbs, foods, vitamins, minerals, dietary supplements. |

| 4 Manipulative and body-based methods | These methods include chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, and massage. |

| 5 Energy therapies | Energy therapies involve the use of energy fields. They are of 2 types: |

As the evidence-base for some CAM increases, medical practitioners have a legal obligation to inform patients of the efficacy of relevant complementary therapies as treatment options, and to simultaneously be aware of the potential for adverse events and interactions that CAMs, such as nutritional and herbal supplements, may have when co-administered with pharmaceutical drugs or when a patient denies good orthodox care for any unproven CAM.11 Knowledge in the efficacy of a complementary medicine or therapy is essential when making clinical decisions for patient care to help weigh against potential risks, such as adverse reactions or delays in useful conventional treatment. This highlights the importance of medical practitioners having at least basic education in the area of CAM to enable them to communicate and inform patients about what therapies are appropriate to the individual. Education on potential risks such as nutrient toxicity, especially with single nutrient use, and any potential interactions with pharmaceuticals is also essential.

Popularity of IM and CAM

Worldwide reports demonstrate that a large proportion of the public are using CAM and its popularity is increasing. For example, in Australia up to 70% of the population are using CAM.12 In the United States, up to 62% of adults use CAM.13 It is therefore vital that health and medical practitioners are well informed about the evidence in these areas.

In many respects, the enthusiasm to use CAM is largely driven by the public. The community has greater access to information and various complementary medicine practitioners and therapies. There are often various reasons why a patient will want to trial CAM. These include philosophical and cultural reasons — wanting a more holistic approach to health care, when there are no longer any other orthodox approaches to assist in their health care, especially if they have suffered any adverse events from orthodox treatments. Generally, patients who use CAM are not rejecting orthodox medicine but are looking for options to improve wellbeing. Unfortunately, medical practitioners underestimate the extent of use of CAM by patients.14, 15 This is of great concern, considering the potential for adverse events such as herb–drug interactions and coordinating the overall management of the patient.

Cultural aspects in determining type of CAM use

The WHO estimates that approximately 60% of medicine that is practiced worldwide is traditional medicine.16 Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is practised in many Asian countries, Ayurveda medicine in India, Unani medicine in the Middle-East, Pakistan and India, while Kampo medicine is used in Japan. Biomedicine or conventional medicine is the predominant medicine practised in developed countries and its formation has also been influenced by cultural factors.17

IM strategies and healing

A holistic approach to health care involves giving comprehensive lifestyle advice that is inclusive of physical, social, psychological, emotional and spiritual wellbeing. In this way, we are encouraging and promoting our patients to take personal responsibility and be active participants for their own health. The focus needs to be on wellness, and not specifically on the disease. Positive lifestyle changes and a typical integrative approach to assist healing that can work alongside conventional medicine to improve health outcome or quality of life are listed in Table 1.2.

| Lifestyle suggestions |

Health practitioner/doctor and patient satisfaction

Most studies actually indicate that over 80% of patients are satisfied with their general practitioner especially if they see the same doctor frequently.18 A questionnaire of 869 patients demonstrated that trust and commitment was positively associated with adherence to treatment. Positive relationships were also associated with adherence to treatment and commitment, and between trust and commitment, that led to positive lifestyle choices, such as healthy eating habits.19 The researchers concluded:

Patients’ trust in their physician and commitment to the relationship offer a more complete understanding of the patient–physician relationship. In addition, trust and commitment favourably influence patients’ health behaviours.18

It is also vital that patients are encouraged to take responsibility for their health and be well informed about all treatments (conventional or complementary) that are safe and suitable for their health care (see Tables 1.3 and 1.4).

| The holistic health care practitioner encourages patient responsibility by: |

|---|

| Empowering patients to be active participants in their health care |

| Promoting self-care |

| Helping patients to make informed decisions and choices |

| Respecting choices |

| Being honest about limitations |

Table 1.4 The well-informed patient

| The well-informed patient: |

|---|

| Chooses not to be passive |

| Actively sources material and information about their disease |

| Works together with their health care practitioner to achieve common goals based on mutual respect |

| Participates in their own health care |

| Is motivated to get better |

| Needs close monitoring and discussion if they refuse orthodox treatment — this requires careful documentation in clinical notes |

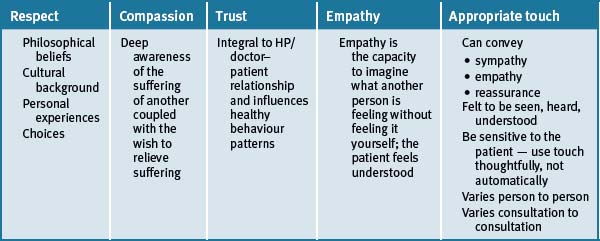

Respect for the patient and their choice of treatment, compassion, trust and empathetic understanding all positively influence the HP/doctor–patient relationship, and help adherence to therapeutic regimens (see Table 1.5).20, 21, 22

Other factors that influence the HP/doctor–patient relationship:

HP/doctor–patient relationship and the ‘doctor’ as the teacher

The value of long clinical consultations

Longer patient-centred consultations are of benefit for those patients with chronic disease or mental health problems. The Australasian Integrative Medicine Association (AIMA) evaluated the evidence of long clinical consultations and the impact on quality of health. The results demonstrated that long consultations:23

Mind–body medicine

Communication with allied and CAM practitioners

It is well established that patients are not communicating with medical practitioners about the use of CAM.25, 26 What is not so well established is to what degree the CAM practitioners and regular doctors are communicating. Medical practitioners (MPs) have an established tradition of communicating with each other e.g. specialists (consultants) with general practitioners (GPs). A specialist knows that in general the GP will have some idea about the content of what they are communicating, as medical graduates would have had at least some exposure to do with the various medical specialties during their medical courses and postgraduate training. If a homeopath was to communicate with a GP there are major difficulties as most GPs would either have no or little knowledge or understanding of homeopathy and the language behind it. Many patients do not communicate with their regular doctor about CAM use for fear of being misunderstood or jeopardising their doctor–patient relationship. However, studies indicate that patients prefer that GPs were more educated about the CAMs they use, so that they can then better communicate with their doctors about their use of CAMs.12

Referrals to regulated CAM practitioners such as osteopaths, chiropractors (in most states and territories of Australia) and TCM practitioners (Australia), reduces the risk of incompetent management. If the CAM practitioner is a member of a professional body this can provide evidence of at least some training, standards and guidelines for safe practise.

It is also reassuring to the MP if it is known that the CAM practitioner has adequate experience and in particular is aware of their limitations and knows when to refer back to a MP. The MP should initially be involved if a diagnosis has to be made but this would not be necessary if a patient wanted, for example, dietary advice or wanted to learn relaxation techniques which could be obtained from a CAM practitioner. As a ground rule, MPs differentiate between medical and CAM practitioners and have expressed greater confidence in medical colleagues who practice complementary medicine.27, 28

There are unresolved issues to do with referrals by MPs to CAM practitioners and these include:29

Ethical and legal Issues

A report on ethical and legal issues at the interface of CAM and conventional medicine suggests that when MPs are faced with patients wanting to trial CAM they should:30

The abovementioned points serve as useful guidelines for MPs in consultations involving CAM.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM)

The definition of evidence-based medicine (EBM) is ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’.31 EBM integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients’ choice. Furthermore it is noted that absence of evidence does not mean a therapy does not work.32

EBM is a common term described as:

the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice.31

Biomedical focus on evidence-based medicine and evidence-based research affecting IM and CAM

Scientific evidence is the basis and is pivotal to biomedicine. Evidence on efficacy and safety should be the basis of defining which CAMs are useful and which are not. To date, research in CAM has been limited due to a number of factors such as funding, the type of CAM used, the quality of the studies, the ability to patent a product and so forth, to make any firm conclusions about their potential role in health care. In saying this, there is also a large body of scientific evidence emerging for CAM worldwide. This evidence should be made accessible to the health profession and public, and also integrated into recommended national guidelines of treatment for specific health conditions. Once a therapy or medicine, be it orthodox or complementary, has scientific evidence to prove its efficacy and safety, then the medical practitioner has a legal and ethical obligation to use the best treatment possible for the individual patient.

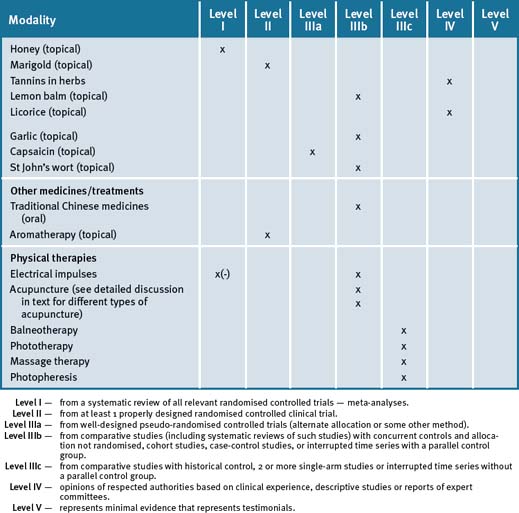

National and Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines to research

Since 1999, the National and Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC)33 has created useful guidelines to identify the varying levels of scientific evidence using a scale from I–IV. These guidelines help to identify which medicines or therapies carry greater weight in research, with Level I considered as superior research and Level IV considered the least superior. Refer to Table 1.6

| Level I | From a systematic review of all relevant randomised controlled trials, meta-analyses. |

| Level II | From at least 1 properly designed randomised controlled clinical trial. |

| Level IIIa | From well-designed pseudo-randomised controlled trials (alternate allocation or some other method). |

| Level IIIb | From comparative studies (including systematic reviews of such studies) with concurrent controls and allocation not randomised, cohort studies, case-control studies, or interrupted time series with a parallel control group. |

| Level IIIc | From comparative studies with historical control, 2 or more single-arm studies or interrupted time series without a parallel control group. |

| Level IV | Opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies or reports of expert committees. |

| Level V | Represents minimal evidence from testimonials. |

Conclusion

The basic principles of holistic health care include:

1 Kotsirilos V. Complementary and alternative medicine. Part 2-evidence and implications for GPs. Australian Family Physician. 2005;34(8):689-691.

2 See websites for the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP — http://www.racgp.org.au) and the Australasian Integrative Medicine Association (AIMA — http://www.aima.net.au/).

3 Snyderman R., Weil A.T. Integrative medicine: bringing medicine back to its roots. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):395-397.

4 Vitetta L., Anton B., Cortizo F., et al. Mind-body medicine: stress and its impact on overall health and longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1057:492-505.

5 Ford E.S., Bergmann M.M., Kröger J., et al. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition–Potsdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1355-1362.

6 Kotsirilos V. Complementary and alternative medicine. Part 1-what does it all mean? Australian Family Physician. 2005;34(7):595-597.

7 RACGP-AIMA Joint Position Statement of the RACGP and AIMA. Complementary Medicine, 2004, Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/Content/NavigationMenu/Advocacy/RACGPpositionstatements/2006compmedstatement.pdf (accessed 14-04-09)

8 Vitetta L. Integration is here to stay. Editorial. J Compl Med. 2008;7(6):7.

9 Integrative Medicine Statement. See Statement Chapters in RACGP Curriculum for Australian General Practice. Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/curriculum (accessed 14-04-09)

10 National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). What is Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM)?May 2002, USA. Last modified. 21, October 2002. Online. Available: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/ (accessed 14-08-09)

11 Brophy E. Informed consent and complementary medicine. J Comp Med. 2003:223-228.

12 Easton K. Complementary medicines: attitudes and information needs of consumers and health care professionals. Prepared for the National Prescribing Service Limited (NPS). July 2007.

13 Patricia M., Barnes M.A., Eve Powell-Griner, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States. Seminars in Integrative Medicine. June 2004;2(2):54-71.

14 Kristoffersen. SS, cited in Drew AK, Myers SP. Safety issues in herbal medicine: implications for the health professions. MJA. 1997;166:538-541.

15 Nahin RL, Straus SE. Research into complementary and alternative medicine: problems and potential. BMJ 322 (7279):161

16 World Health Organization. Media Centre fact sheets. Online. Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/ (accessed Jan 2010)

17 Cassidy C.M., et al. Commentary on terminology and therapeutic principles: challenges in classifying complementary and alternative medicine practices. J Altern Comp Med. 2002;8:893-895.

18 Potiriadis M., Chondros P., Gilchrist G., et al. How do Australian patients rate their general practitioner? A descriptive study using the General Practice Assessment Questionnaire. MJA. 2008;189(4):215-219.

19 Berry L.L., Parish J.T., Janakiraman R., et al. Patients’ commitment to their primary physician and why it matters. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(1):6-13.

20 Marie-Thérèse Lussier. Claude Richard. Feeling understood. Expression of empathy during medical consultations. Canadian Family Physician. 2007;53:640-641.

21 Squier R.W. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner–patient relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(3):325-339.

22 Branch W.T., Malik T.K. Using ‘windows of opportunities’ in brief interviews to understand patients’ concerns. JAIMA. 1993;269(13):1667-1668.

23 Cohen M., Kotsirilos V., Hassed C., et al. Long Consultations and Quality of Care: AIMA Position Statement. Journal of the Australasian Integrative Medicine Association (JAIMA). Oct 2002;19:19-22.

24 Sali A, Vitetta L. Integrative medicine. In: the Mix. Australian Doctor 2007; 20 April: 39–40.

25 MacLennan A.H., Wilson D.H., Taylor A.W. The escalating cost and prevalence of alternative medicine. Prev Med. 2002;35:166-173.

26 Tillem J. Utilisation of complementary and alternative medicine among rheumatology patients. Integrative Medicine. 2000;2:143-144.

27 Marshall R., Gee R., Israel N., et al. The use of alternative therapies by Auckland general practitioners. NZ Med J. 1990;103:213-215.

28 Pirotta Marie, Cohen Marc, Kotsirilos Vicki, et al. Complementary therapies: have they become accepted in General Practice? MJA. 2000;172:105-109.

29 Brophy E. Referral to CM practitioners — legal and ethical issues. J Comp Med. 2003;2:42-48.

30 Kerridge I., McPhee J. Ethical and legal issues at the interface of complementary medicine and conventional medicine. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;181:164-166.

31 Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M.C., Muir Gray J.A., et al. Editorial: Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71-72. Online. Available: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/312/7023/71?eaf (accessed 13-01-09)

32 Altman Douglas G., Martin Bland J. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311:19. August: 485

33 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 1999.