Chapter 1. Introduction

Immediate assessment of the critically ill

In order to address this issue, the organisation of the medical care of the critically ill patient has undergone a revolution in recent years. Inter-professional demarcation is being removed, with the development of multidisciplinary teams. The nurses within these teams have extended skills in the recognition and management of the acutely ill medical patient. These teams have a number of overriding principles:

1. Core competencies in the management of the critically ill

2. Immediate access to appropriately skilled team members

3. Effective prioritisation – assessing and treating the sickest patients first

4. Emphasis on the immediate identification of patients who are critically ill, who are deteriorating or who are at risk of deterioration

5. The need to initiate appropriate corrective action and to know who to call for help and with what degree of urgency

6. A reduction in duplication of work such as multiple admission clerking

This process has been facilitated by the development of Early Warning Systems based on simple nursing observations. These should identify patients who require urgent intervention and who may need prompt detailed assessment from the medical staff or, increasingly, from a Critical Care Team. Examples of such teams include Medical Emergency Teams and nurse-led Critical Care Outreach Teams.

ABCDE: Immediate Assessment and Intervention

Immediate survival depends on urgent attention to the safety of the critically ill patient – the Airway, the Breathing, the Circulation. Subsequent progress depends on a more comprehensive assessment – by measuring Disability and Exposing the patient for detailed examination. This plan of immediate action based on the mnemonic ‘ABCDE’ is a recurring theme in the book – emphasising the critical importance of urgent and effective resuscitation. Urgent initial treatment may have to proceed in the absence of a definite diagnosis. However, a detailed assessment will be necessary to make a comprehensive diagnosis and to plan subsequent management; to do this requires a history, examination and an understanding of the underlying medical conditions. Each chapter therefore emphasises both the immediate safety of the patient and the nature, mechanisms and management of the underlying disease. The challenge for the nurse is to integrate this very technically demanding work with a humane and caring approach, combining modern clinical expertise with traditional nursing skills.

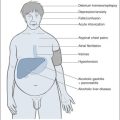

The first chapter gives an overview of the initial assessment and the early management which will be necessary to ensure the patient’s immediate survival. Fig. 1.1 provides a summary of the most urgent nursing observations – matched with the corrective interventions that may be necessary – and page references to relevant sections in the book. Detailed descriptions of resuscitation in specific conditions appear in later chapters.

|

|

| Fig. 1.1 |

It is important to develop a structured and systematic approach to immediate resuscitation. The focus should be on two fundamental issues: getting oxygen into the blood (Airway and Breathing) and getting blood (Circulation) to the brain and kidneys. The format for the initial assessment (→Fig. 1.1) is based on the primary survey performed by first response teams such as the ambulance crew, and is founded on the standard ABCDE system in which the most important observations are performed first and the problems that are identified are rectified before moving on to the next stage. The primary survey is repeated when the patient is admitted to the ward; its structure ensures that the immediate safety of the patient continues to be addressed.

Subsequent progress is monitored from a number of basic physiological measurements obtained using standard nursing observations (the ‘vital signs’):

• the respiratory rate

• pulse rate

• oxygen saturations

• blood pressure

• consciousness level

• urine output

• temperature

Early Warning: Track and Trigger Systems

In response to criticisms that critically ill medical patients are not recognised soon enough and that resuscitative measures are delayed, inadequate, or both, a number of tools have been developed that utilise the observation of vital signs to identify patients who are at risk. These tools, sometimes known as ‘Track and Trigger’ systems, are used to monitor progress (track) and to provide specific criteria which, when met, trigger a call for assistance with a view to urgent corrective intervention.

The aim is to prevent any patient passing through an unrecognised yet potentially reversible period of instability and deterioration. The most common events preceding a cardiac arrest or transfer to ITU are a falling blood pressure and a reduction in the level of consciousness.

The most common system in use scores each observation according to its value. For example, in the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), a urine output of less than 0.5ml/kg per hour scores 2 points, whereas between 1 and 3ml/kg per hour scores 0. Scores from each observation are added up, and the total used to determine the level of action. Depending on the total score, this will vary from a simple increase in the frequency of observations to an urgent review by middle-grade medical staff. It is important that there is an explicit protocol to match the score with the action that is required. As the score increases there should be an appropriate escalation of the response. The nature of the protocol will depend on local circumstances: in some Units, for example, the nurses are authorised to order tests and initiate treatments once a certain level of score is reached, whereas in others the response may simply be based on calling for escalating levels of assistance. In many Units, an important and effective development has been the availability of nurseled Critical Care Outreach Teams which can react rapidly to deteriorating warning scores by advising and initiating early interventions and liaising with the High Dependency Unit and Intensive Therapy Unit. Once the staff have responded and a management plan is in place, the assessment tools are used to monitor improvement and to provide a mechanism to ensure that patients who fail to improve are identified and re-assessed within explicit time-frames.

It is important, therefore, that any Early Warning protocol should have a time element within it. When every staff member is hard pressed and there are competing clinical priorities, it is vital that there is a clear and mutual understanding of the expected response times; in one system, for example, the maximum response time for a doctor is 1h for an oxygen saturation of 90% and a systolic blood pressure of 90mmHg, but 15min when both values are only 80. Another system specifies the following maximum time intervals: patient first triggering a response and the attendance of the doctor, 25min for an SHO; if the patient continues to trigger despite intervention, 70min for the registrar; if there is continuing concern, 120min for discussion with the on-call consultant.

Examples of ‘Track and Trigger’ Systems

1. Single-parameter calling criteria (→Table 1.1)

All respiratory arrests

Respiratory rate <8/min

Respiratory rate >25/min

Saturations on oxygen <90%

Pulse rate <45 beats/min

Pulse rate >125 beats/min

Systolic blood pressure <90mmHg

Sudden fall in level of consciousness

(Fall in GCS of >2 points)

Repeated or prolonged seizures

Any patient who does not fit the criteria above, but whom you are seriously worried about

This is simpler than a scoring system, but may be less discriminating between those who do and do not need urgent intervention.

2. A multiple-parameter scoring system

A total score of 3 or more in the Early Warning Score (EWS; →Table 1.2) triggers a contact with the outreach team, and the patient should be rescored hourly. There is a Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), which includes an assessment of the urine output and attempts to relate the changes in blood pressure to the patient’s normal values. The SEWS (Scottish Early Warning Score) also incorporates a measurement of oxygen saturation – as an example an oxygen saturation of 88% scores 2: a total score of ≥ 4 triggers an urgent medical review (within 20 minutes).

| A, alert; V, responds to voice; P, responds to pain; U, unconscious | |||||||

| Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| HR (beats/min) | <40 | 41–50 | 51–100 | 101–110 | 111–130 | >130 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | <70 | 71–80 | 81–100 | 101–199 | >200 | ||

| RR (breaths/min) | <8 | 9–14 | 15–20 | 21–29 | >30 | ||

| Temp. (°C) | <35.0 | 35.1–36.5 | 36.6–37.4 | >37.5 | |||

| CNS | A | V | P | U | |||

Conclusion

Whatever assessment tool is used and whatever staff are involved, the fundamental issues are the identification of any patient who is at risk and to ensure that the staff who are giving the care have the appropriate skills in the management of the critically ill. These tools should be seen as an aid to assessment; they do not replace common sense or intuition (‘there is something not quite right here’), and they do not acknowledge the need to intervene when there are distressing symptoms or unrelieved suffering. They also do not recognise the critical role of history taking or that of the relatives in recognising change. One of the most telling signs of the at-risk patient is the next of kin who wants to see a doctor because of their increasing anxieties over the deterioration of their relative’s condition.

Further Reading

Ball, C.; Kirkby, M.; Williams, S., Effect of the critical care outreach team on patient survival to discharge from hospital and readmission to critical care: non-randomised population based study, British Medical Journal 327 (2003) 1014–1016.

Chellel, A.; Fraser, L.; Fender, V., Nursing observations on ward patients at risk of critical illness, Nursing Times 98 (46) (2002) 36–39.

Websites

NHS Modernisation Agency, Critical Care Outreach. (2003) ; http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/06/35/00/04063500.pdf.

Acutely ill patients in hospital: NICE guidelines: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG50/NICE guidance/pdf/English.