Chapter 1 Introduction

The purpose of this book is to help students and practitioners of complementary therapies extend their skills in clinical diagnosis and integrative case management. As complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) educators, we recognised our students’ need for specific guidance in diagnosis and treatment prioritisation, along with the effective integration of a range of modalities into individualised holistic treatment programs. This style of case analysis was developed to provide students, teachers and practitioners with a framework within which they could effectively analyse and classify the extensive amount of information gathered in a CAM consultation [1]. We expect this book will be of particular benefit to CAM students and recent graduates who are seeking tools to enhance practice, particularly those who are learning or practising in countries in which CAM practitioners are not primary healthcare providers.

Detailed explanations for specific treatment protocols and modalities are not included in each case because we have assumed our target readership has an understanding of basic CAM principles, herbal therapy and actions, along with nutritional and dietary protocols. Readers who are unfamiliar with these concepts are directed to the outline of the fundamental principles and practice of CAM in Chapter 2, and subsequently listed reference materials; these recommend some excellent resources.

The process of case analysis and decision making outlined in this book can help the user develop effective and appropriate treatment protocols within the time constraints of a busy clinic [1]. The case analysis format, together with the case studies in this book, have been used with great success in quite different CAM training institutions. Students found the decision-making framework extremely helpful, despite training within differing models of CAM. The inspiration to develop this book came from seeing how this method allowed student practitioners to collate facts and relate the information collected into an understanding of how the underlying issues connected to the presenting symptoms [5]. The case analysis framework is deliberately simplistic so it can be adapted for all models of CAM, and the analysis method presented can be used as a scaffolding on which varying levels of complexity can be formed into a holistic understanding of the general and specific needs of the individual client.

How to use this book

The first section focuses on diagnostic analysis from a holistic perspective, taking into account both individual and common themes for specific disease conditions. The questioning protocols are focused on initial consultations; however, they can be adapted for use in subsequent consultations. It concludes with a decision table for referral, outlining referral flags, issues of significance and referral options with suggestions for further medical investigations. Additionally, a table of investigations for integrated holistic analysis is presented in Appendix B.

The three C’s case analysis formula

Clinical questions

Clinical questioning has been divided into three main sections called the three C’s:

• Complaint – questions to define the client’s presenting complaint. The aim is to understand the complaint.

• Context – questions to put the presenting complaint into context. The aim is to understand the disease. Questions on common contributing physical, dietary and lifestyle factors that may trigger the presenting complaint and lead to differential diagnosis considerations.

• Core – questions for holistic assessment to understand the client. Questions to reveal unique contributing emotional, mental, spiritual, metaphysical, lifestyle and constitutional factors for the individual client.

Although these categories have been set out in three chronological sections, it may be necessary to interweave the three lines of questioning throughout the consultation. How the questioning unfolds will depend upon the discretion of the practitioner, information-gathering priorities and rapport building with the client. The client may dictate which areas of information they wish to share, which will influence how the practitioner approaches questioning and information gathering. The examples of open and closed questions presented in this book have been designed to encourage confidence in the practitioner. Specific question examples may seem to extend beyond the level of qualification and jurisdiction of a non-primary practitioner. These questions have been included to help practitioners recognise symptoms and situations where referral to other healthcare providers is necessary. It is not our intention to encourage CAM practitioners to take over the role of primary healthcare professionals when that is beyond the scope of their training and professional boundaries. The purpose of these questions is to suggest ways in which CAM practitioners can elicit information that link the language of orthodox differential diagnosis into the observations and understandings acquired during the consultation process [7].

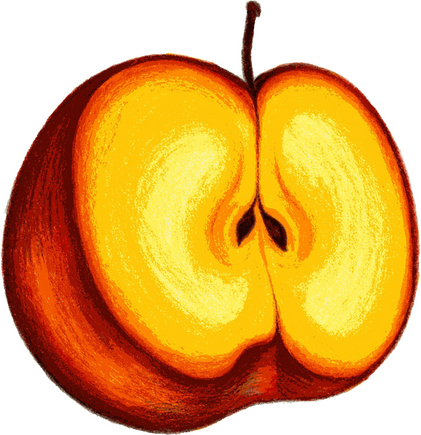

The ‘apple’ analogy

The three C’s formula is woven into the clinical questions, case analysis, referral suggestions and treatment options for all cases studies presented in this book. To more

clearly illustrate this concept, we have likened the framework to the analogy of an apple, which consists of three distinct and purposeful layers.

1. The skin of the apple can be likened to the ‘complaint’, providing a first impression and surface information about why the client has come for help. This section shows us the cover that has developed as the underlying issues progress and manifest outwardly. For example, a feeling of fatigue is a ‘complaint’ symptom for which several reasons may need to be considered in order for it to be put into context.

2. The layers of physiological, environmental and lifestyle triggers of illness that are commonly shared or implicated in the development of conditions is the flesh of the apple, corresponding to the ‘context’. This flesh is usually significant and helps identify the cause of complaint symptoms, which may be common to a number of different individuals. For example, if a group of people with low thyroid function experience fatigue, then the shared complaint symptom of fatigue can be understood within a common context for that disease process.

3. The underlying issues at the heart of the apple make up the core emotional and lifestyle triggers that are unique to each individual. The ‘core’ of an apple houses the seed in the same way that we house the seed of our illness. This is where an understanding of the metaphysical/spiritual/emotional influences on illness plays an important role, with consideration that physical manifestations of disease have an underlying energetic or emotional beginning [13, 18, 19]. If unique stressors for individuals are recognised as the seeds that can develop into illness, the core section can be the gateway to understanding how to let go of the cycle of ill health and move towards wellness. The reasons an individual is vulnerable to compromised health are unique to that person and understanding those reasons is the key to holistic healing.

By using the framework of the three C’s formula it is possible to consider a case from a holistic perspective. If an individual is experiencing extreme stress due to their struggle to make life decisions based on their own values and beliefs rather than those of others (core), this stress may contribute to thyroid imbalance (context), thus causing the surface symptom of fatigue (complaint). In using this example we recognise the medical fact that hypothyroidism may cause fatigue and there is no biomedical evidence that hypothyroidism can result from the inability to make life decisions; however, chronic stress has been linked to the development and progression of a range of medical conditions including immune dysregulation [19]. It is therefore possible to see how chronic stress caused by an emotional conflict could trigger or worsen underlying immune-related thyroid dysfunction [19, 21]. We hope readers will be open to the concept of individual beginnings to common themes of illness. In offering this analogy as a suggested means of exploring individual cases, we are by no means suggesting this is the only way to perceive the causes of health imbalance in individuals with specific health conditions but rather suggesting that the three C’s formula framework is useful in holistically analysing cases.

Mnemonics

To further assist the reader we have developed mnemonics that guide the questions and case analysis. Mnemonics have been linked to the three C’s case analysis formula and the ‘apple analogy’ explanation. The interweaving of these three tools allows the reader to follow the logic and flow of how the cases presented in this book have been analysed and treatment decisions have been determined. Question examples linked to mnemonics have been offered for each case as a working tool to help guide the the reader. We have intentionally included only a limited number of questions in each case and the reader is encouraged to refer to Appendix A for a more extensive list of clinical question examples. The reader can assume that in each case the practitioner would question the client extensively and cover all important/relevant body systems and symptoms. The extensive questions list in Appendix A list has been included to help guide readers with their own cases. To understand more thoroughly how the suggested mnemonics and questions can be incorporated into general case taking, one case example is provided at the end of Chapter 2 demonstrating more extensive questioning than has been applied to the other cases in this book.

The cases

Diagnosis

Each case in this book begins with a fictional case study including relevant medical investigations and physical examination history. We have deliberately limited information in the initial case presentation to allow readers to use their own diagnostic analysis skills to determine which specific questions are required to come up with a differential diagnosis list. To assist readers, a list of generic clinical questions is presented in Appendix A. A differential diagnosis list and working or confirmed diagnosis has also been provided. Although the title of each case provides the specific diagnosis, we encourage readers to go through the process of case analysis and come up with their

| SKIN OF THE APPLE | FLESH OF THE APPLE | SEED OF THE APPLE |

|---|---|---|

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

| Understand the complaint | Understand the disease | Understand the client |

own differential and working diagnoses before referring to the diagnostic information provided for each case.

Decision tables

Referral flags and issues of significance

‘Referral’ and ‘issues of significance’ flags are included in the decision table for referral to indicate symptom priority. Referral flags are symptoms that indicate the possibility of serious organic disease or the potential of harm to the client, and which require immediate referral to a primary healthcare practitioner [3]. ‘Issues of significance’ symptoms are not as urgent as referral flags but still need to be addressed. These symptoms may be benign but could also indicate more serious conditions and may require referral and collaborative case management at some stage.

Referral

Cases have been presented as either requiring immediate referral for medical diagnosis and collaborative management once diagnosis has been confirmed, or those that do not necessarily require immediate referral to a primary healthcare practitioner before CAM treatment is commenced. In the second instance, treatment recommendations are given and collaborative referral is recommended where appropriate. We have assumed that most readers of this book will be auxiliary practitioners rather than primary practitioners, and referral suggestions are based on this premise.

Treatment

The second section of each case provides holistic integrative treatment and lifestyle recommendations, with guidelines for managing the case in the context of the individual needs of the client. The decision table in this section is focused on assisting readers to formulate and prioritise a treatment program that reflects the complaint, context and core issues. Treatment suggestions have been presented in accordance with CAM principles starting with minimal active intervention and progressing through to greater levels of active intervention. In each case treatment recommendations cover commonly used CAM modalities beginning with recommendations for lifestyle and dietary interventions followed by physical treatment suggestions, and herbal and nutritional supplement suggestions. Treatment recommendations combine both evidence-based and traditional treatment approaches, which reflects the approach to treatment followed by many CAM practitioners [10, 24].

We believe the application of a Western scientific biomedical paradigm to some CAM modalities is not always helpful or even possible. A lack of scientific evidence for a specific CAM treatment or approach does not invalidate its use but can indicate the limitations of applying an evidence-based biomedical conceptual framework to certain CAM modalities and approaches [10, 12, 23, 25]. In such instances, for research to provide a truthful appraisal it must be done in a manner that incorporates and maintains the modality’s underlying concepts and approaches to health and healing [8, 12, 22, 25, 26]. Traditional use can also be considered to be valid evidence based on the many years of use and traditional knowledge [9–11].

Integrating CAM and conventional medicine

We acknowledge that several CAM modalities do not require orthodox medical diagnosis in order to effectively treat clients [4]; however, our book suggests a way this can be incorporated into healthcare management that provides benefits for both mainstream and complementary medicine. Integrating these aspects has the potential to enhance holistic diagnosis and treatment options along with providing an opportunity for positive collaboration with mainstream medical practitioners and allied health professionals [14–16]. Indeed, failure to detect underlying pathology may result in the progression of an illness into a more serious organic disease [3, 14]. As integration between CAM and mainstream medicine continues to unfold, mainstream medical practitioners are now more likely to train in areas of complementary medicine [16, 17, 20], and CAM practitioners may have additional training in an aspect of conventional medicine such as nursing, physiotherapy or medicine itself [3].

The referral recommendations in this book are not intended to fit every CAM model, and we recognise that CAM practice has various levels of primary care status globally, which will inevitably influence the priority of referral and which symptoms can be treated. We believe we are offering referral suggestions that include the varied legal and professional boundaries of CAM practitioners by encouraging referral that embraces the concept of open support from allied health professionals. These cases do not set out the definitive way to approach case management; rather, we present the idea of referral within the context of professional boundaries that focuses on the best interests of the client, who may want to be better ‘informed’ from a variety of perspectives regarding diagnosis and treatment options [7]. Achieving this balance can be difficult, and effective cross-referral and collaborative case management is reliant on the willingness of all health professionals to be open to different paradigms of health [3, 7].

Because fundamental paradigms and methodology can differ so significantly, clients and practitioners may find diagnostic and treatment information from a range of perspectives confusing and conflicting [3, 4]. However, discussing the various perspectives and concepts with clients can be a positive experience for both the client and the practitioner if open communication is achieved [3]. Often genuine clarity comes with inner debate, reflection and questioning, and personal growth can be embraced through illness [9]. We believe that through this process clients can gain a clearer understanding, which can inform their personal choices as they make decisions about treatment and their journey towards wellness. Therefore, collaboration between healthcare practitioners can provide clients with a much more effective outcome [2, 7] and increases the likelihood of meeting all of the client’s needs [2]. Holistic healthcare is far more than using a variety of CAM modalities but involves collaboration and cooperation between all of a client’s healthcare practitioners [2, 6]. It is encouraging to note that recent Australian research has revealed medical practitioners are now more open to accepting the role of CAM practitioners in overall healthcare [3, 6].

The diagnostic and decision-making framework in this book can help readers become more confident in making sound treatment decisions by means of thorough analysis of the client’s case history and individual needs. This is an area of weakness for some CAM practitioners, as highlighted by a 2005 La Trobe University report [3] that identified a number of risk areas for Australian naturopathic and Western herbal medicine practitioners. These risk areas include: poor prescribing; failure to recognise contraindications; inappropriate dosage and duration of therapy; lack of understanding of drug/nutrient/herbal interaction; failure to detect underlying pathology; misdiagnosis; failure to refer; and failure to disclose or offer informed consent [3]. This could be considered the responsibility of the practitioner and, in response to these concerns, we hope our book will offer students and practitioners effective tools to ensure higher standards of clinical care and treatment.

[1] Lloyd M., Bor R. Communication skills for medicine, third edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

[2] El-Hashemy S. Naturopathic standards of primary care. Toronto: CCNM Press; 2008.

[3] McCabe P. Tertiary education in naturopathy and western herbal medicine. In: Lin V., Bensoussan A., Myers S., et al. The practice and regulatory requirements of naturopathy and western herbal medicine. Melbourne: School of Public Health, La Trobe University, 2005. Available from <www.health.vic.gov.au/pracreg/naturopathy.htm> [accessed 18 October 2008]

[4] Jagtenberg T., Evans S. Global Herbal Medicine: A Critique. The Journal of Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(2):321–329.

[5] Ashcroft K., Foreman-Peck L. Learning and the reflective practitioner. In: in: Managing Teaching and Learning in Further and Higher Education. London: Falmer Press; 1994.

[6] Southern D.M., Young D., Dunt D., Appleby N.J., Batterham R.W. Integration of primary healthcare services: perceptions of Australian general practitioners, non-general practitioner health service providers and consumers at the general practice-primary care interface. Evolution and Program Planning. 2002;25(1):47–59.

[7] Jeroen D.H., Van Wijngaarden A.A., de Bront R.H. Learning to cross boundaries: The integration of a health network to deliver seamless care. Health Policy. 2006;79(2–3):203–213.

[8] Butelow S., Kenealy T. Evidence-based medicine: the need for a new definition. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2000;6(2):85–92.

[9] Mills S., Bone K. Principles & Practice of Phytotherapy; Modern Herbal Medicine. Edinburgh: London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

[10] Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs & Natural Supplements: An evidence based guide, second edn. Sydney: Elsevier; 2007.

[11] Guidelines for Levels and Kinds of Evidence to Support Indications and Claims For Non-Registerable Medicines, including ComplementaryMedicines, and other Listable Medicines. Therapeutic Goods Administration of Australia, 2001. Retrieved 16 March 2010. http://www.tga.gov.au/docs/html/tgaccevi.htm

[12] Nahin R.L., Straus S.E. Research into complementary and alternative medicine: problems and potential. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:161–164.

[13] Tataryn D.J. Paradigms of health and disease: a framework for classifying and understanding complementary and alternative medicine. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(6):877–892.

[14] Cohen M. Practitioners and ‘regular’ doctors: Is integration possible? Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;180:645–646.

[15] Kerridge I.H. J.R. McPhee, Ethical and legal issues at the interface of complementary and conventional medicine. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;181(3):164–166.

[16] Owen D.K., Lewith G., Stephens C.R. Can doctors respond to patients’ increasing interest in complementary and alternative medicine? British Medical Journal. 2001;322:154–158.

[17] Pirotta M., Cohen M., Kotsirilos V., Farish S.J. Complementary therapies: have they become accepted in general practice?,. Medical Journal of Australia. 2000;172:105–109.

[18] Kiecolt-Glaser J.K., Glaser R. Depression and immune function: Central pathways to morbidity and mortality. Journal of Psychomatic Research. 2002;53:873–876.

[19] Cohen S., Janicki-Deverts D., Miller G.E. Psychological Stress and Disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687.

[20] Levine S., Weber-Levine M., Mayberry R. Complementary and alternative medical practices: Training, experience and attitudes of a primary care medical school faculty. Journal American Board of Family Practice. 2003;16(4):318–326.

[21] Prummel M.F., Strieder T., Wiersinga W.M. The environment and autoimmune thyroid diseases. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;150:605–618.

[22] Long A.F. Outcome Measurement in Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Unpicking the Effects. Journal Altern Complement Med. 2002;8(6):777–786.

[23] Gaylord S.A., Mann J.D. Rationales for CAM Education in Health Professions Training Programs, Acad Med. 2007;82:927–933.

[24] Eastwood H.L. Complementary therapies: the appeal to general practitioners. Medical Journal of Australia. 2000;173:95–98.

[25] Tonelli M.R., Callahan T.C. Why Alternative Medicine Cannot Be Evidence-based. Acad Med. 2001;76:1213–1220.

[26] Sarris J., Wardle J. Clinical Naturopathy, an evidence-based guide to practice. Australia: Elsevier; 2010.