Introduction

If you have not already done so, stand up and give yourself a big hug. PASS Congratulations! You have managed to stand the pressure, heartache and pain of two of the hardest exams you will ever sit. The written exams are over; no more ambiguous questions, no more basic science, and no more exam halls. Be proud of yourself; there is but one more hurdle …

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF THIS BOOK

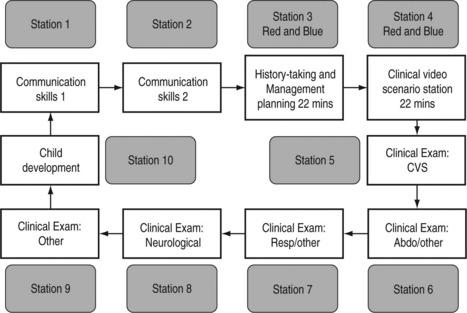

The prototype circuit is shown below and this should be well known to you, as should all the information on the College website (www.rcpch.2ac.uk.). You should study the website as not only does it explain the circuit in great detail but also it will keep you up to date on any subtle changes. Example questions can be found by going to the website, selecting ‘Publications’ and then clicking on ‘Publications Section’. An alphabetical list will be shown; click on ‘Examinations’ and you will be given all documentation pertaining to all three membership exams. You will find example questions as well as information for candidates and examiners (both worth looking at).

The basic examination circuit is represented in the diagram below:

• 1 examiner per station, none for clinical video scenario stations.

• 10 examiners for the circuit, 1 additional examiner for back-up/quality assurance.

• Candidates join at each station of the circuit, making 12 in total per circuit.

• 2 candidates join at the History taking and Management planning stations and 2 at the Clinical video scenar station at any one time.

• In total there are 10 objective assessments per candidate.

• The History-taking and Management planning stations and the Clinical video scenario stations are 22 minutes in length, with the other 8 stations being of 9 minutes’ duration.

• There are 4-minute breaks between each station, with the entire circuit taking 152 minutes to complete.

• The sequence in which a candidate takes the stations in the circuit will vary.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, October 2004. MRCPCH Clinical Examination www.repch.ac.uk/publications/examinations_documents/Web_Circuit.pdf

Each station is 9 minutes long, except the history-taking and management PASS planning station, which lasts 22 minutes. In the exam the 9 minutes seem to disappear as quickly as butter on a hot day so you must be swift (but not rushed) in the clinical stations. Of the six clinical stations, cardiology, neurology and development must be covered. There is generic advice that two of the other three stations should be respiratory and abdominal but this is not an absolute.

1. At first read-through the book may appear a bit ‘wordy’. A lot of the detail in the answer sections is actually based around the exam process rather than hard fact. Much of this needn’t be read in detail second time round as they are easy points to learn. The key clinical information will be found in highlighted tables and boxes.

2. The scenarios may appear vague in places. The aim is not to deliberately confuse but to recreate some of the dilemmas you actually have in the exam. No situation in medicine is ever black and white. Unlike previous revision texts there are few classic cases in this book. Too often candidates learn ideal descriptions of pathology or syndromes but when presented with the case in the exam they either don’t actually recognize those features – e.g. what does a shagreen patch look like in tuberous sclerosis? – or they don’t have the features you think they should (only 15% of those with neurofibromatosis have optic glioma). Before looking at the answer to the question write down a list of differentials. How much do you know about each of the conditions on that list?

3. The book contains very few pictures. The reason is that there are not many good pictures available on the public domain and most are already used in paediatric textbooks. These conditions are easy to recognise and don’t represent the children you will have in the exam. Obviously text cannot replace actually seeing the child in question but it will focus your mind on the important features to look for.

4. Before looking at the answer make sure you go through in your head all the questions you would have asked the parent/patient or which systems you would have examined more closely. You will be lulled into a false sense of security if you read a question, spend 10 seconds thinking about your response and then look at the answers.

5. An answer is given for the clinical stations. However, it may not always have been possible to get that answer from the information given. This is to avoid classic scenarios being given which do not encourage active thought. The answer is provided to help when rereading chapters to quickly refresh your memory about the learning points of the station.

6. The answers are designed to direct further revision. They will present a structure to answering the station and provide helpful hints about that particular condition. In some cases they will give you a definitive conclusion as to the case but, as you will discover in the exam, you do not necessarily have to be spot on to pass the station. Nor does getting the right diagnosis mean you have fulfilled the examiner’s instructions.

7. No apology is made for the occasional repetition of information or similarity between some stations. In researching this book it has become obvious that certain information and themes pop up all too frequently.

8. When you start getting annoyed that the information given is lacking in places and the answer isn’t definite because you know of confounding issues, then you are ready to take the exam!

Below is some general advice for each of the stations in the circuits. It is worth reading this before looking at the first chapter. From then on there is no set way to proceed. Individually it can be used chapter by chapter to ensure you are covering the important points and are not missing key information. The first couple of chapters may be used as you start revising to give you direction. You may return to the book later to check your progress. In groups the chapters will facilitate discussion about topics and will provide a large amount of scope for practice role-play. It is hoped clinicians who have membership but have not taken the new exam will use it to aid their own teaching. I would also recommend watching House or renting previous series on DVD. The medicine is very silly but almost every episode requires you to come up with a differential for presenting symptoms. Of course these are either often PASS adults, exceedingly rare or a result of House’s own treatment! They do require you to think on the spot, though. Do not go into the exam having never been challenged to produce a list of differentials on the spur of the moment.

CARDIOLOGY

Confident presentation is important in all parts of the exam but can be especially difficult because the examiner knows what the murmur is, and you are either right or wrong. On close questioning the candidates may be tempted to change their diagnosis three or four times on the basis of a raised eyebrow! Unfortunately there are few ‘soft’ signs; you need to know your AS from your PS and not get ADD about ASD*Importantly, your examination findings must tally with your diagnosis. The examiner will forgive you for missing the inconsequential tricuspid regurgitation but not if you tell him a systolic murmur at the left sternal edge is mitral stenosis. It is generally accepted that it is wiser to leave the diagnosis until you have presented your findings. One of the authors opted for the converse approach and was fortunately right, although he spent the rest of the 9 minutes answering difficult questions – perhaps best to waste time talking!

If you still have the box from your Littmann stethoscope you may find a CD of common heart murmurs in it – or try www.dartmouth.edu/~clipp/demo_case.htm and log on as a guest for a very good cardiology-type station.

ABDO/RESPIRATORY/OTHER

Without going into the realms of specific examination there is honestly little new to say with regard to these stations apart from the fact that practice makes perfect! They are classic short cases and should be treated as such. You are given 4 minutes’ preparation time before the station, and although the station may be ‘other’, the time is well spent rehearsing your examination flow and reminding yourself of differential lists. By the time you have walked into the room, had the story explained, introduced yourself and positioned the patient you will be well into your 9 minutes of time. It will go quickly so make sure the exam is precise but slick. It is therefore important you know how long your examinations take you. You should be able to perform a good abdominal or respiratory exam in a couple of minutes. If you are taking 5 minutes the examiner will get bored and stop you. It is very useful to watch other candidates examining but all too easy to criticise other people’s techniques. Feedback is vital from registrars who have passed the exam.

DEVELOPMENT

For many candidates who sit the exam this station is the greatest unknown. A simple idea in theory, it is one of the most difficult to revise for. Obviously a sound knowledge of developmental milestones is necessary but the skill is in the interpretation and testing of them. You may be able to say a 2-year-old has not reached his milestones but do you know why? Do you know where he is PASS at the moment? Is his apparent deficit a result of another delayed milestone?

CANDIDATE INFORMATION

This station assesses your ability to deal with a clinical problem.

This is a 9-minute station consisting of spoken interaction. You will have up to 2 minutes before the start of the station to read this sheet and prepare yourself. You may make notes on the paper provided.

You are: An SpR in paediatrics.

Setting: Side room of paediatric ward during a Sunday morning ward round.

YOU ARE NOT EXPECTED TO GATHER THE REST OF THE MEDICAL HISTORY DURING THIS CONSULTATION.

ROLE-PLAYER INFORMATION

You breast-fed him for 2 weeks but your milk dried up.

After the doctor has explained the situation to you, your feelings and further questions are:

• What are the potential problems/side effects?

• Will it delay the investigations for his jaundice?

• What will be done by the hospital to prevent it happening again?

What to expect from the candidate, and how to respond:

The main thing is to be CONSISTENT with your story and emotional response with each candidate.

EXAMINER INFORMATION (page one)

This station assesses the candidate’s ability to deal with a clinical problem.

INFORMATION GIVEN TO ROLE-PLAYER:

You breast-fed him for 2 weeks but your milk dried up.

David has not eaten today. He is jaundiced and has stopped breathing briefly. He is currently receiving oxygen via a tube under his nose and is on a saturation monitor.

GUIDE NOTES TOWARDS EXPECTED STANDARD:

• Appropriate conduct of interview.

• An explanation to the parents of how the error occurred.

To apologise for the reported mistake.

To apologise for the reported mistake.

• To recap the situation and to invite parents’ questions about the possible toxic effects to David and how these will be monitored.

To detail the actions necessary which will include:

To detail the actions necessary which will include:

– notification of an adverse incident to the Hospital Trust.

– to document fully in the medical records of the patient the prescribing error and actions taken.

EXAMINER INFORMATION (page two)

Please use this sheet to make a list of the criteria you have used in this station to decide if a candidate is a clear pass, pass, bare fail or clear fail and hand it to the host examiner when you have completed the circuit.

HISTORY-TAKING/MANAGEMENT PLANNING

Make time to be observed taking a focused history of a new referral to an PASS outpatient clinic to a consultant or senior registrar (this may well be difficult to organise). It is amazing when being observed how under pressure you feeland what simple things you forget to ask. Remember this is managementplanning in a non-acute scenario. Simply requesting bloods is unlikely to bethe answer. Referral to other centres and disciplines is likely to be a usefulprocess; remember you are acting as a first-year registrar.

Clinic experience is essential to understanding the process behind thesestations.

PLAYING THE GAME

There is something distinctly unusual about having your every word and movement monitored. Just this act of observation can reduce good trainee paediatricians to the level of a newly qualified foundation grade. The only other time you are observed in this way, with so much pressure riding on the result, is medical finals and your driving test. I am no longer ashamed to say that I passed my driving test on my seventh – yes seventh, attempt. At the time I was the laughing stock of my peers – a seemingly intelligent, motivated and able sixth-form student cracking under the pressure of a three-point turn. In hindsight there were a few reasons why this occurred. I failed my first test with a D (dangerous driving!) as a result of just not being ready for the exam. I was practically much improved on the second attempt but I had this nagging doubt in my mind. Most of my peers passed first time or, at the worst, second time round. What would happen if I failed? With that small seed planted I spent most of the test paranoid that every little mistake I made was being held against me. At one stage I thought I had pulled out in front of someone and glimpsed the examiner placing a cross on his sheet. I was furious, stopped concentrating and then made a string of small but costly errors. In fact I had not failed for my initial mistake, and had I not got so distracted by this I probably would have passed. Unfortunately my obsession with what the examiner was doing resulted in failures in tests ASS3, 4, 5 and 6 as well. There are numerous lessons to be learnt here:

1. Don’t let me drive you anywhere.

2. Do not sit the exam until you are ready. You must seek an honest opinion from a senior colleague who knows you well and has seen you examine patients. You are doing yourself no favours by failing badly on your first attempt. It will damage your confidence and you lose the benefit of having taken the exam early to speed up your time through the system.

3. You must learn to stop thinking about the examiner and concentrate on the patient. Be truly interested in diagnosing the condition the child has. This sounds cheesy but unless you are focusing all your efforts on the child then you are wasting the knowledge and time you have spent getting to the exam.

4. You have not failed until the College sends you a letter telling you, ‘You’ve failed!’. I realise this is flippant but there is no point spending £300 to give up after two stations because you feel it is all over.

5. Although the college won’t let you take the exam seven times in a row, if you truly believe in yourself you stand a much better chance of passing. I have seen candidates go into the exam with that seed of doubt already planted; it will sprout very quickly in the heat of the exam circuit.

Dress well and look the part. This means:

• Wear glasses as opposed to contacts if you are not sure which to wear.

• Don’t wear a ridiculous tie unless you have a consistent personality to match. Ask senior physicians if you come across as too flamboyant or too quiet.

• Be videoed at least once examining a real or mock patient. Watch yourself. Are there any mannerisms you have which you need to alter? Do you speak too quickly? Are you as clear in your pronunciation as you thought?

• You look like you are not sure. If you spend 3 minutes listening to the same spot on the precordium or ask the child to walk seven times across the room, you simply do not look confident. If you do not have a definitive answer simply describe what you have seen or heard. You can then give your most likely differentials. Remember, not all the children in the exam need to be given a diagnosis to pass.

• You have provided inconsistent information. ‘This pink and well-perfused 7-year-old child has a loud murmur at the left sternal edge. There are no scars to see. This child may have a VSD or Fallot’s tetralogy.’ Stupid example but it is very easy to say things under pressure. The examiners understand this and just want to make sure you don’t actually mean what you have just said.

You show controlled anger.

You show controlled anger. You want to know why this has happened.

You want to know why this has happened.