Introduction

Incidence

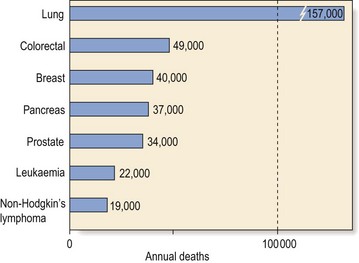

Leukaemia is not a common disorder but it is a significant cause of death from cancer (Fig 19.1). There is a male preponderance in most types of leukaemia. Geographic variations exist; for instance, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is the predominant form of leukaemia in the Western world but is much less frequent in Japan, South America and Africa.

Aetiology

Genetic abnormalities

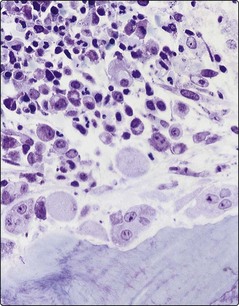

Cytogenetic analysis and particularly molecular genetic techniques have revealed various acquired non-random chromosomal derangements which play a fundamental role in leukaemogenesis (Fig 19.2). There are a number of different types of possible chromosomal change.

Fig 19.2 Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) study of a complex karyotype (including t(8;16) ) in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia.

Predisposing factors

In a small subpopulation of leukaemic patients there is another obvious predisposing factor – the more common of these are listed in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1

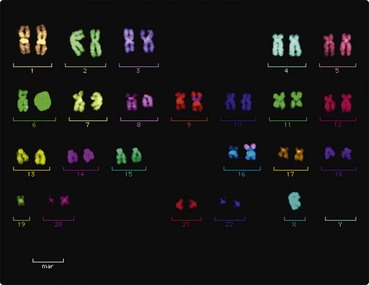

Cytotoxic chemotherapy, particularly with alkylating agents, leads to an increased risk of leukaemia (Fig 19.3). The risk appears to be greatest in older patients also treated with radiotherapy. The best established occupational leukaemogenic exposure is undoubtedly to benzene. A number of genetically determined diseases also predispose to leukaemia. Here the liability to leukaemia is probably caused by factors such as increased chromosomal breakage (e.g. Fanconi’s anaemia) and immunosuppression (e.g. ataxia telangiectasia).

Fig 19.3 Peripheral blood film in a young woman with acute myeloid leukaemia.

She had received chemotherapy for choriocarcinoma several years previously.

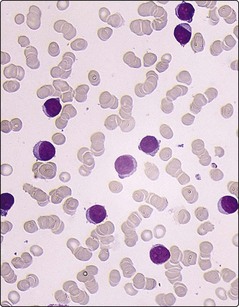

Viruses are known to be the main cause of leukaemia in many animals but in humans the only well-proven association is of the HTLV-1 virus with the rare disorder T-cell leukaemia lymphoma (Fig 19.4). Myelodysplastic syndromes (pp. 50–51) and myeloproliferative disorders (pp. 64–67) may transform to acute myeloid leukaemia.

Classification

In such a potentially complex group of disorders it is helpful to use a relatively simple classification. The leukaemias can most broadly be divided into acute and chronic types depending on their clinical course. The classification illustrated here (Table 19.2) further divides leukaemias into their cell of origin (i.e. myeloid or lymphoid) and refers to the microscopic appearance (morphology) of the leukaemic cells. The traditional classification of the acute leukaemias is that of the FAB group – the abbreviation being for the French, American and British nationalities of the terminologists – but this has been overtaken by the World Health Organization (WHO) system. Basic morphological techniques (e.g. microscopic inspection of a blood film and bone marrow sample) remain important in the initial diagnosis but cytogenetic and molecular genetic techniques are becoming increasingly important in classification as acquired genetic changes frequently have prognostic significance and can guide treatment.

Table 19.2

| Acute leukaemia | Acute myeloid leukaemia |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | |

| Chronic leukaemia | Chronic myeloid leukaemia |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | |

| Other types | Hairy cell leukaemia |

| Prolymphocytic leukaemia | |

| T-cell leukaemia lymphoma |