Intravenous fluid therapy

Does this patient need IV fluids?

Does this patient need IV fluids?

How much fluid should be given?

How much fluid should be given?

Which IV fluids should be given?

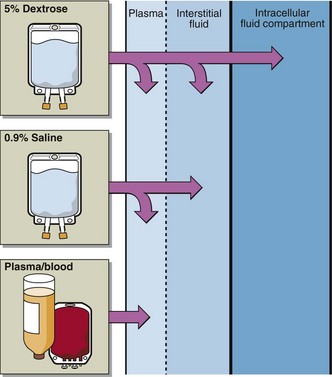

The list of intravenous fluids that is available for prescription in many hospital formularies is long and potentially bewildering. However, with a few exceptions, many of these fluids are variations on the three basic types of fluid shown in Figure 13.1.

Fig 13.1 The three types of fluid usually used in intravenous fluid therapy are shown here with the different contributions they make to the body fluid compartments.

Plasma, whole blood, or plasma expanders. These replace deficits in the vascular compartment only. They are indicated where there is a reduction in the blood volume due to blood loss from whatever cause. Such solutions are sometimes referred to as ‘colloids’ to distinguish them from ‘crystalloids’. Colloidal particles in solution cannot pass through the (semipermeable) capillary membrane, in contrast with crystalloid particles like sodium and chloride ions, which can. This is why they are confined to the vascular compartment, whereas sodium chloride (‘saline’) solutions are distributed throughout the entire ECF.

Plasma, whole blood, or plasma expanders. These replace deficits in the vascular compartment only. They are indicated where there is a reduction in the blood volume due to blood loss from whatever cause. Such solutions are sometimes referred to as ‘colloids’ to distinguish them from ‘crystalloids’. Colloidal particles in solution cannot pass through the (semipermeable) capillary membrane, in contrast with crystalloid particles like sodium and chloride ions, which can. This is why they are confined to the vascular compartment, whereas sodium chloride (‘saline’) solutions are distributed throughout the entire ECF.

Isotonic sodium chloride (0.9% NaCl). It is called isotonic because its effective osmolality, or tonicity, is similar to that of the ECF. Once it is administered it is confined to the ECF and is indicated where there is a reduced ECF volume, as, for example, in sodium depletion.

Isotonic sodium chloride (0.9% NaCl). It is called isotonic because its effective osmolality, or tonicity, is similar to that of the ECF. Once it is administered it is confined to the ECF and is indicated where there is a reduced ECF volume, as, for example, in sodium depletion.

Water. If pure water were infused it would haemolyse blood cells as it enters the vein. Water should instead be given as 5% dextrose (glucose), which, like 0.9% saline, is isotonic with plasma initially. The dextrose is rapidly metabolized. The water that remains is distributed evenly through all body compartments and contributes to both ECF and ICF. Five per cent dextrose is, therefore, designed to replace deficits in total body water, e.g. in most hypernatraemic patients, rather than those specifically with reduced ECF volume.

Water. If pure water were infused it would haemolyse blood cells as it enters the vein. Water should instead be given as 5% dextrose (glucose), which, like 0.9% saline, is isotonic with plasma initially. The dextrose is rapidly metabolized. The water that remains is distributed evenly through all body compartments and contributes to both ECF and ICF. Five per cent dextrose is, therefore, designed to replace deficits in total body water, e.g. in most hypernatraemic patients, rather than those specifically with reduced ECF volume.

How should the fluid therapy be monitored?

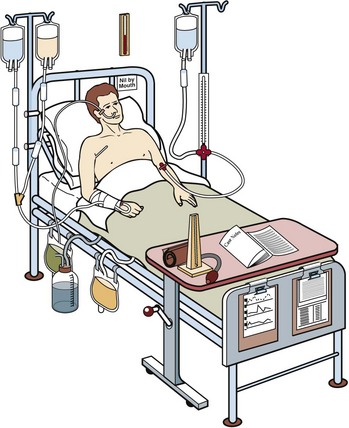

The best place to study monitoring of IV fluid replacement in practice is in the intensive care setting. Here, comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s fluid and electrolyte balance (Fig 13.2) allows the prescribed fluid regimen to be tailored to the patient’s individual requirement.