10 Intraocular Inflammation

The uveal tract consists of the iris, ciliary body and choroid lying in continuity; inflammation in this tract is known as uveitis. Uveitis can be classified according to the principal site of inflammation as anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis (a subgroup of which is pars planitis), posterior uveitis or panuveitis. Because the uveal tract is continuous, severe inflammation in one part may be accompanied by signs of overspill inflammation in another. For example, a severe anterior uveitis (iritis) may be accompanied by a cellular infiltrate in the anterior vitreous (some ophthalmologists would term this an iridocyclitis). Conversely, posterior uveitis may be accompanied by signs of inflammation in the anterior chamber; furthermore, diseases included under the umbrella of posterior uveitis often have significant retinal signs.

SIGNS OF UVEITIS

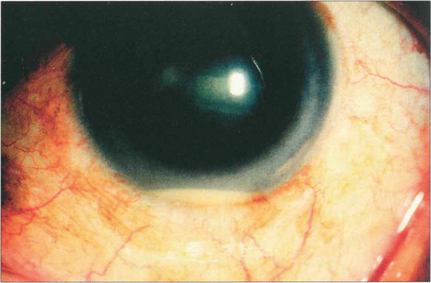

Fig. 10.1 Ciliary injection is seen here in its classical form as a dusky red circumlimbal vasodilatation in the area around the cornea where the ciliary and scleroconjunctival circulations anastomose. Its degree reflects the acuteness and severity of inflammation in the anterior uveal tract. With very severe inflammation the whole of the bulbar conjunctiva can be involved and the appearances may be difficult to distinguish from the diffuse appearance of conjunctival inflammation.

By courtesy of Dr J Krachmer.

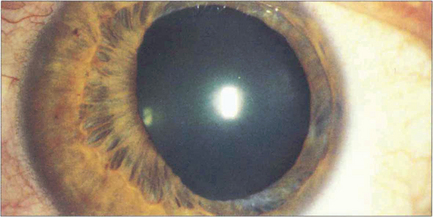

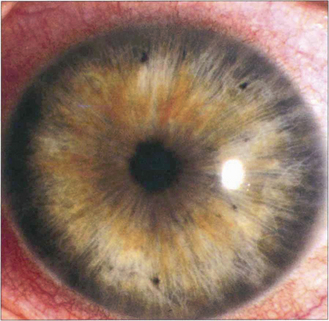

Fig. 10.2 Cells in the anterior chamber are a sign of active inflammation within the eye. The cells are leucocytes that circulate in the convection currents present within the anterior chamber. In the slit-lamp beam they have an appearance similar to that of particles of dust in a sunbeam. They are best seen by a narrow high-intensity beam directed obliquely across the anterior chamber.

Fig. 10.3 A flare within the aqueous humour is the result of a raised protein concentration from breakdown of the blood–aqueous barrier together with locally synthesized immunoglobulin. It defines the slit-lamp beam within the anterior chamber rather like a car headlight cutting through a foggy night. Cells usually accompany flare but flare often persists for some time after the cells have disappeared indicating persistent vascular damage rather than active inflammation.

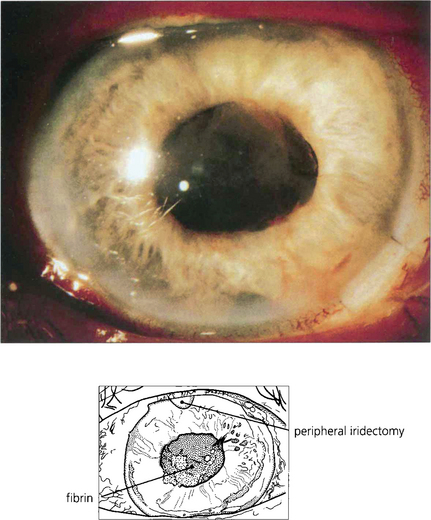

Fig. 10.4 Severe vascular damage, usually seen with really acute inflammation, infection or following surgery will allow even the largest plasma proteins to exude into the aqueous humour. Such exudation is manifested by fibrin, which clots in the anterior chamber to produce the ‘plastic’ uveitis so typical of HLA-B27-associated acute anterior uveitis.

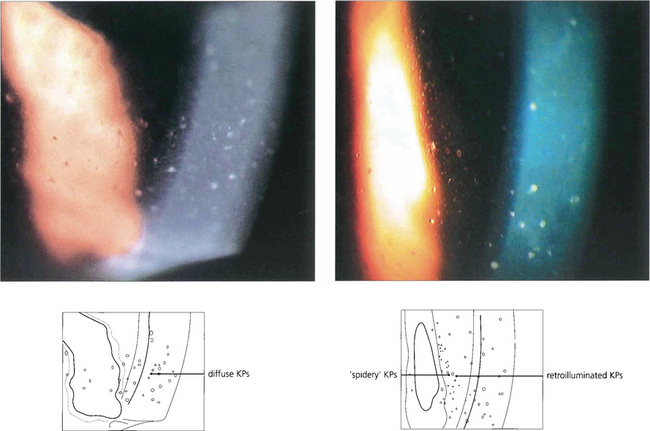

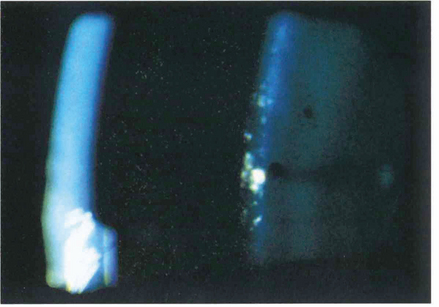

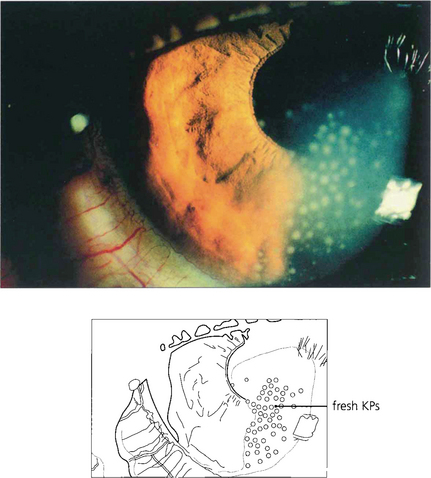

Fig. 10.5 Cells within the anterior chamber circulate through the aqueous humour to agglutinate and become deposited on the corneal endothelium. They are then known as keratic precipitates (KPs) and are one of the classical signs of anterior uveitis. KPs are typically deposited in the inferior quadrant of the cornea, probably because of gravity and convection currents within the aqueous humour. They vary in distribution and number and also in size, colour and shape.

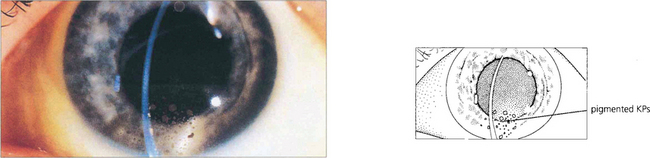

Fig. 10.6 With resolution of the uveitis with treatment or time the KPs will disappear. Chronic KPs tend to become more pigmented, as in this patient. These are typical mutton fat KPs; note the whiteness of the eye.

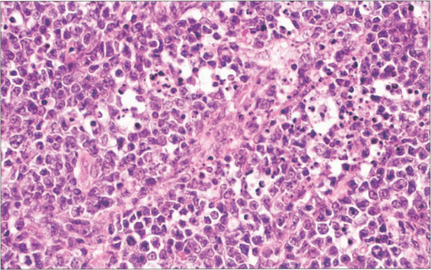

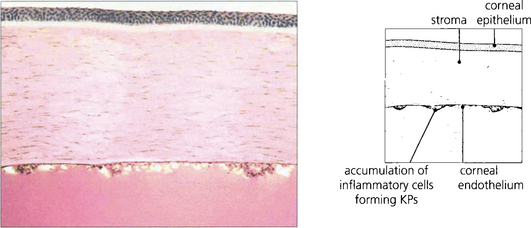

Fig. 10.7 Pathologically KPs consist of a mixture of neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes. Neutrophils predominate in newly formed KPs, whereas macrophages and lymphocytes are deposited later.

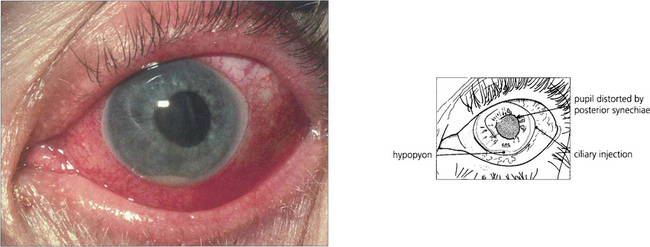

Fig. 10.8 A massive leucocytic response with an acute anterior uveitis can lead to cells precipitating as a hypopyon. This is typical of HLA-B27 positive anterior uveitis but is also seen with other causes of severe anterior uveitis such as Behçet’s disease. Hypopyon may also be the presenting sign of retinoblastoma in children, ocular lymphoma and bacterial or fungal endophthalmitis.

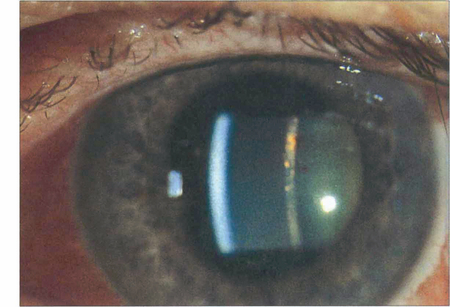

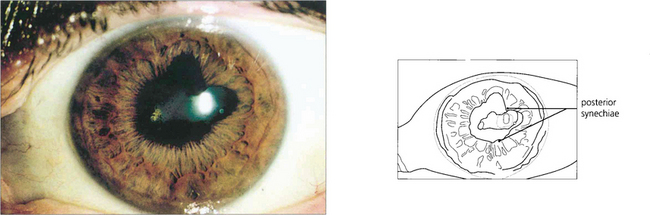

Fig. 10.9 Posterior synechiae are adhesions between the pupillary margin and anterior lens surface; they always reflect a previous anterior uveitis. Pupillary dilatation retracts the iris from contact with the anterior lens capsule and prevents their formation. This is one of the aims of mydriasis in the treatment of uveitis which will sometimes break weak adhesions to leave tell-tale pigment on the lens. Ring adhesions will seclude the pupil and prevent aqueous humour flowing anteriorly, causing iris bombé (see Ch. 8).

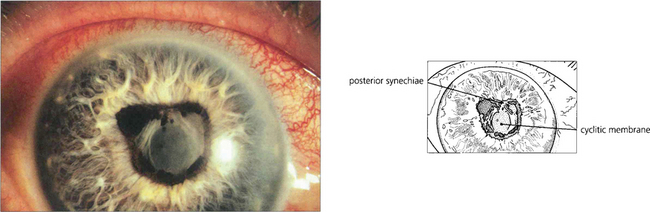

Fig. 10.10 Prolonged and severe inflammation in the anterior chamber produces a cyclitic membrane which can also occlude the pupil.

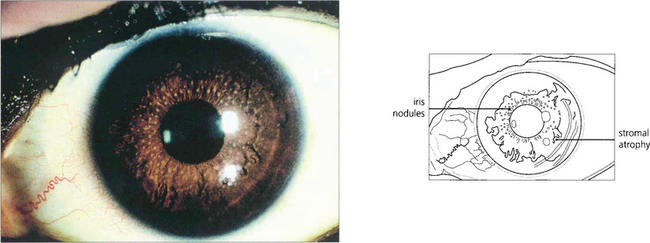

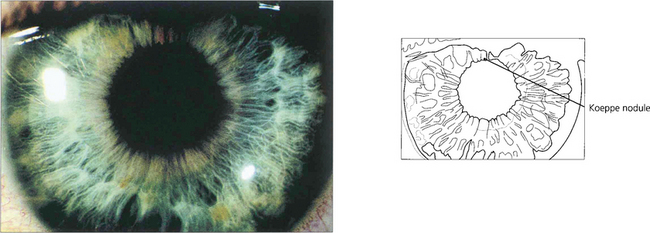

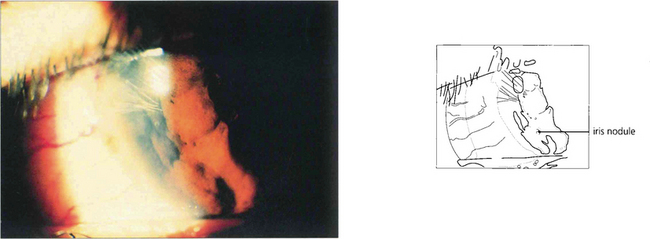

Fig. 10.11 Iris nodules are granulomas. These are known as Busacca nodules when they are in the stroma. At the pupillary margin they are known as Koeppe nodules; posterior synechiae often form at these positions.

Fig. 10.12 Nodules within the peripheral iris stroma can be seen in this patient with a granulomatous uveitis due to sarcoid.

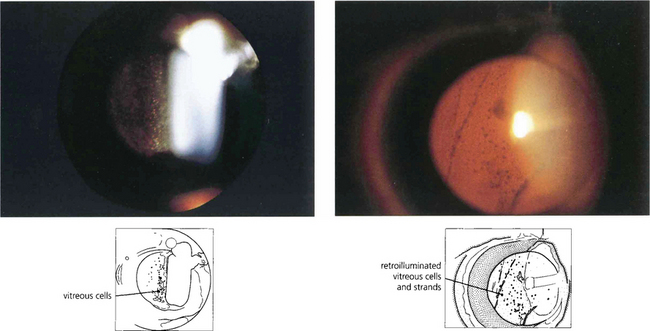

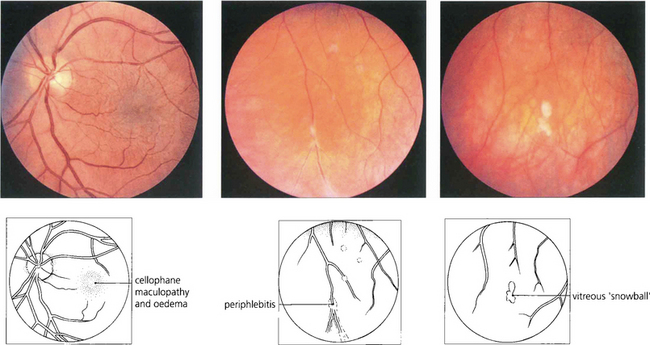

Fig. 10.13 Posterior uveitis produces a cellular vitreous infiltration, analogous to anterior chamber infiltration, but because of the viscosity and structure of the vitreous gel the cells tend to circulate less and persist for longer. Vitreous cells are sometimes distributed more locally, for instance over a focus of chorioretinitis or over the ciliary body. Cells may be distributed as a mass of single cells or accumulate as larger clusters known as ‘snowballs’; they can also be seen as retrohyaloid precipitates on a detached posterior vitreous face. Persistent vitreous inflammation leads to collapse and vitreous detachment with a hazy gel filled with debris.

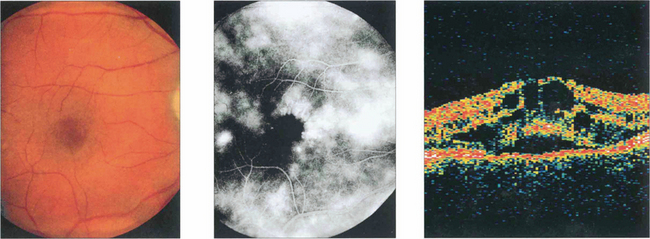

Fig. 10.14 Macular oedema can be seen with posterior uveitis of any type or severity; it is the most common cause of visual loss, although mild degrees can be compatible with normal visual acuity. Depending on the duration and severity of inflammation, the oedema resolves with the uveitis leaving a normal macula or progresses to permanent retinal damage. Macular oedema is often difficult to visualize ophthalmoscopically unless the macula is viewed stereoscopically with a fundus lens (see Ch. 1). Fluorescein angiography can be very useful in its assessment. In mild cases leakage will be seen from the parafoveal retinal capillaries; in more established cases there is pooling of fluorescein within the intraretinal cystoid spaces, giving a petalloid appearance to the angiogram. This patient with mild posterior uveitis had an acuity of 20/60, biomicroscopy showed macular thickening and fluorescein angiography shows marked macular oedema. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) clearly shows the intraretinal cystic spaces and macular thickening.

ANTERIOR UVEITIS

ACUTE ANTERIOR UVEITIS

Ankylosing spondylitis

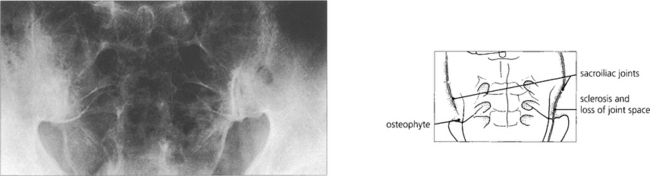

Fig. 10.15 About 50 per cent of HLA-B27-positive patients will have evidence of ankylosing spondylitis which is seen in its earliest form in the sacroiliac joints. There is sclerosis of the periarticular bone with narrowing and irregularity of the joint space, progressing eventually to ankylosis. Similar changes are seen in the spine.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Keratitis (see Ch. 4) and anterior uveitis are common features of herpes zoster ophthalmicus and may occur independently of each other. It is said that keratitis and uveitis are particularly frequent if the vesicles appear along the side of the nose, the cutaneous distribution of the nasociliary nerve that also innervates the iris and pupil but this is not invariably so.

CHRONIC ANTERIOR UVEITIS

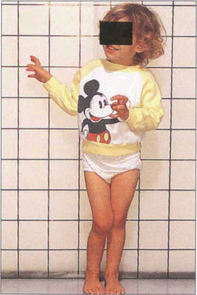

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Fuchs’ heterochromic cyclitis

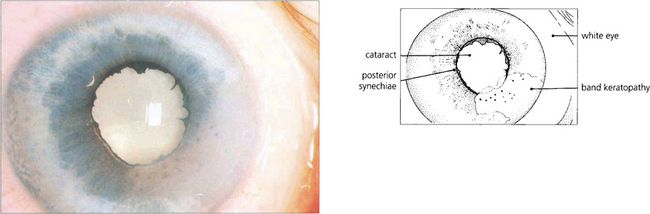

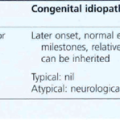

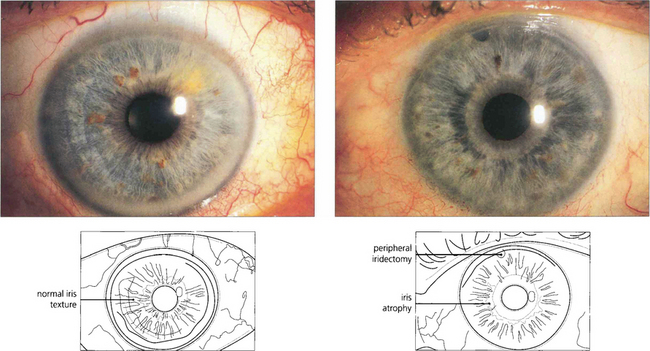

This is a distinctive entity with many features not seen with other forms of uveitis. Small diffuse KPs are scattered over the whole of the corneal endothelium with a fluffy or feathery appearance of their border in contrast to the well circumscribed and inferiorly sited KPs seen with other types of uveitis. The eye is white and posterior synechiae do not form. The iris has a characteristic moth-eaten appearance and becomes de-pigmented, showing a bluish tinge in Caucasian patients. This depigmentation is not as obvious in heavily pigmented eyes where iris stromal atrophy is the hallmark. Heterochromic cyclitis is usually unilateral although bilateral cases rarely occur and are more difficult to diagnose. Glaucoma may develop and is associated with a fine neovascularization of the iris and angle (see Ch. 8). Cataracts are common and are hastened by steroid therapy; the benefit of steroids in this condition is unproven. Histopathological examination of iris specimens shows stromal atrophy with loss of pigment, hyalinization of blood vessel walls, proliferation of vascular endothelial cells and patchy loss of pigment epithelium. There is an inflammatory cell infiltrate of eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes and plasma cells; Russell bodies (immunoglobulins) are present. Recent evidence suggests that the condition is due to persistent localized rubella viral infection.

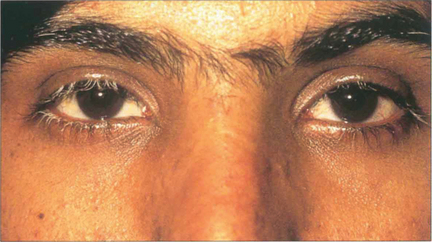

Fig. 10.22 The right eye of this patient is normal but the left shows stromal atrophy consistent with Fuchs’ heterochromic cyclitis. The left iris has a slightly bluish tinge. Note the peripheral iridectomy from previous glaucoma surgery.

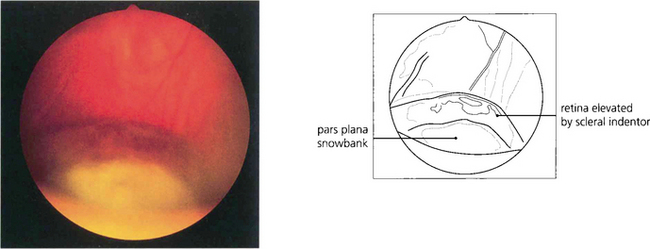

INTERMEDIATE UVEITIS

Fig. 10.26 This 42-year-old man presented with uniocular symptoms but had bilateral signs. The optic disc is normal but there is a trace of macular oedema with wrinkling of the internal limiting membrane causing blurring of vision. There was a low-grade vitreous cellular infiltrate, ‘snowballs’ within the gel inferiorly and periphlebitis of the equatorial retinal veins. The patient was systemically well and all investigations were normal.

POSTERIOR UVEITIS

SYSTEMIC DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH POSTERIOR UVEITIS

Sarcoidosis

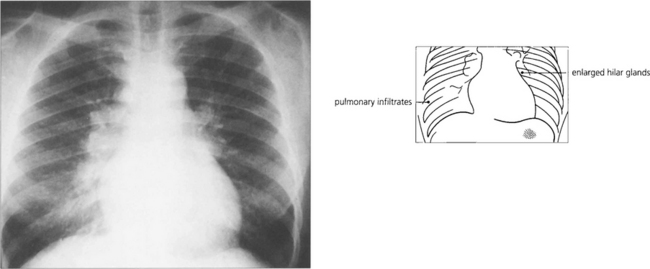

Fig. 10.28 Positive findings of sarcoidosis are found on chest radiography in about 75 per cent of patients, especially in those with recent onset of the disease. These patients may have erythema nodosum. Computed tomography shows the pulmonary changes in better detail. Bronchoscopy, bronchial lavage and biopsy can be useful to confirm the diagnosis. Hilar lymphadenopathy usually resolves spontaneously but systemic steroid therapy may be indicated in the presence of pulmonary interstitial fibrosis.

Fig. 10.29 This 28-year-old woman presented with acute AAU, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and erythema nodosum on her legs.

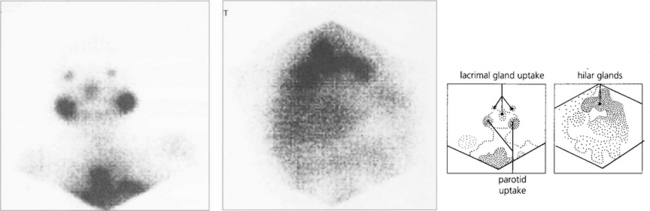

Fig. 10.30 Radioactive gallium is taken up by macrophages in granulomas (not only with sarcoidosis) and can be used to demonstrate the extent of systemic involvement with sarcoidosis. This patient shows uptake in the lacrimal glands, nasopharynx and chest.

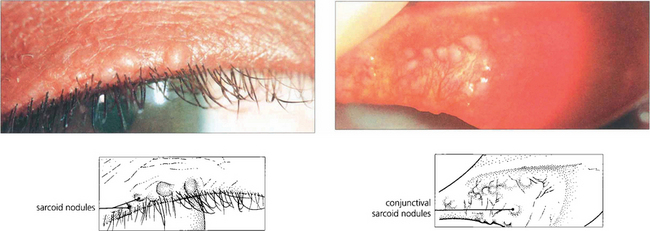

Fig. 10.31 Sarcoid granulomas in this patient are seen along the lid margin and on the tarsal conjunctiva. ‘Blind’ biopsy of normal appearing conjunctiva with multiple sections will sometimes demonstrate noncaseating granulomas.

Fig. 10.32 Lacrimal gland infiltration is common. The gland must be biopsied transcutaneously to avoid damaging the conjunctival ductules and exacerbating the risk of a dry eye. Sarcoidosis is particularly common in African Caribbean patients.

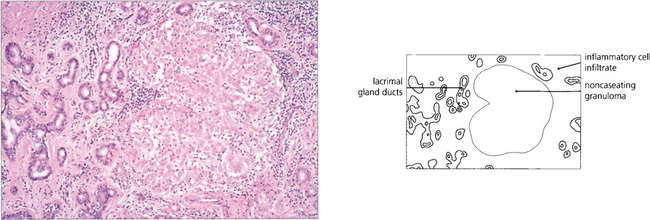

Fig. 10.33 Biopsy of the lacrimal gland shows the typical appearances with a large noncaseating granuloma containing multinucleated giant cells.

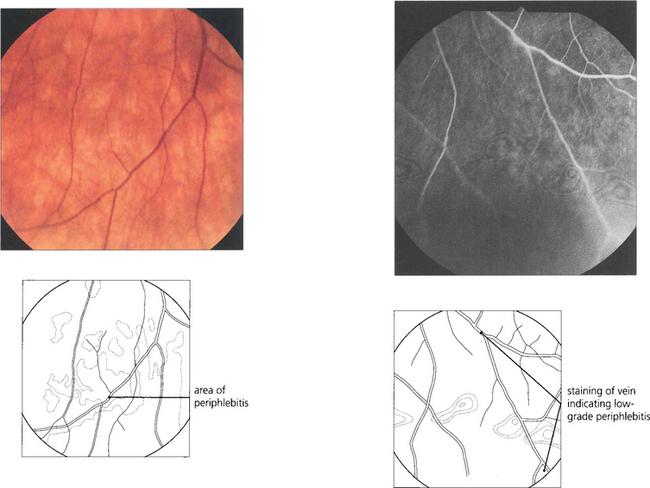

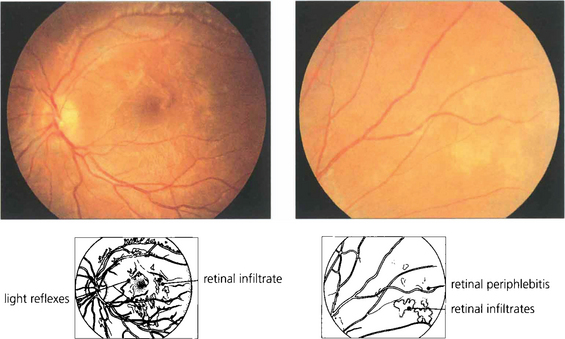

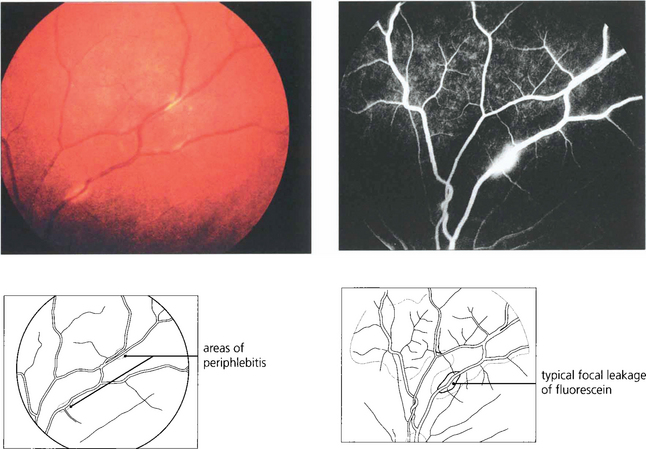

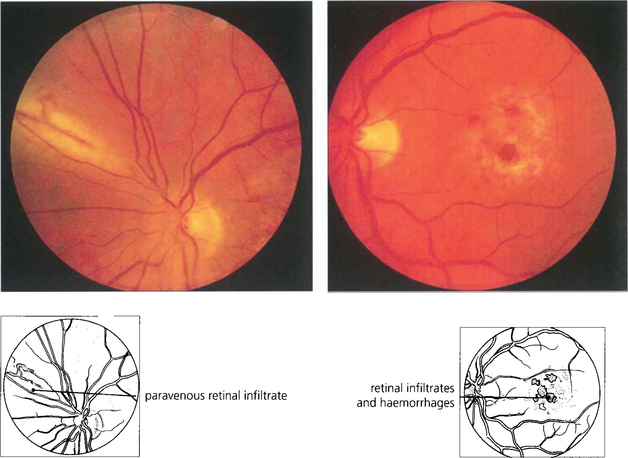

Fig. 10.34 Retinal vasculitis and posterior uveitis can occur in the absence of anterior uveitis; localised areas of focal periphlebitis in the small peripheral retinal veins are almost pathognomic of sarcoidosis. Typically a creamy white infiltrate ‘candle wax’ is seen around the equatorial retinal veins.

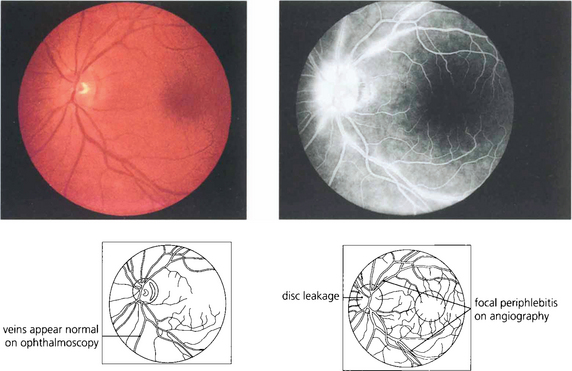

Fig. 10.35 More subtle changes may be observed on fluorescein angiography. This 45-year-old woman presented with a low-grade posterior uveitis. Focal periphlebitis can be seen on the angiogram, suggesting that the patient has sarcoid.

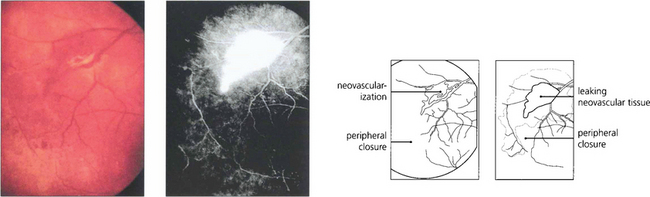

Fig. 10.36 Major venous occlusions, such as central retinal vein occlusion are rare but severe periphlebitis can lead to vascular occlusion and peripheral vascular closure, which may be followed by neovascularization at the border of perfused and nonperfused retina. Neovascularization may also occur at the optic disc. It is amenable to photocoagulation of the areas of capillary closure provided that intraocular inflammation has been adequately suppressed before treatment.

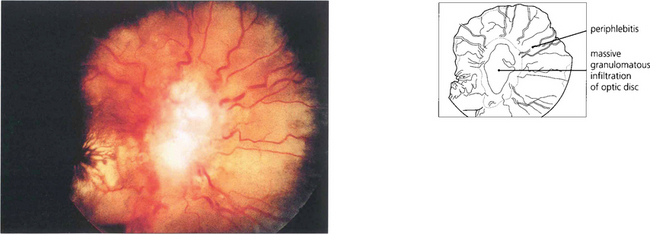

Fig. 10.37 Optic disc swelling may result from local oedema with posterior uveitis, local infiltration with sarcoid granulomata, optic nerve compression by a granuloma at the orbital apex or, occasionally, from raised intracranial pressure with neurosarcoid. Chronic optic nerve infiltration can cause optic atrophy in the absence of disc swelling. This patient with neurosarcoid has a massive granuloma of the disc.

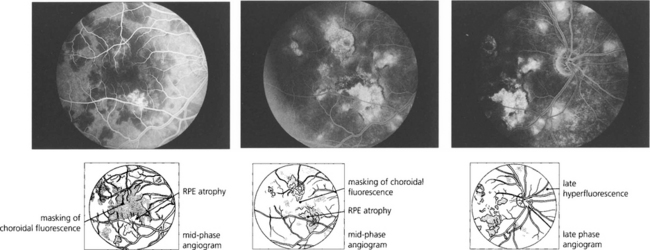

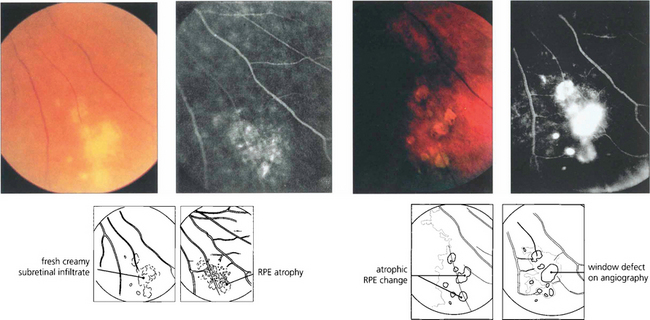

Fig. 10.38 Focal atrophic retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) changes are often seen in the inferior fundus, particularly in middle-aged and elderly women with long-standing disease. They are due to granulomatous change in the RPE or choroid. Initially the lesions have a fluffy creamy appearance that resolves to leave atrophic RPE changes.

Behçet’s disease

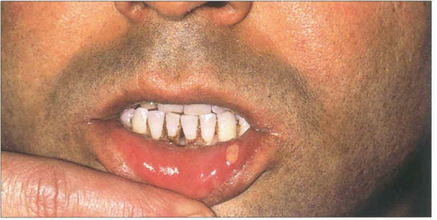

Fig. 10.40 Mouth ulcers are painful and episodic and cannot be distinguished clinically or pathologically from aphthous ulceration. Their presence often predates ocular symptoms sometimes by many years.

Fig. 10.41 Genital ulcers are not seen as frequently as mouth ulcers. This patient has active ulceration but white scars can be seen at sites of previous ulceration.

Fig. 10.42 Recurrent hypopyon is a widely recognized feature of severe Behçet’s disease. There is a brisk cellular reaction in the anterior chamber often with a surprising lack of conjunctival injection. Patients with disease that is confined to the anterior segment alone have a better prognosis.

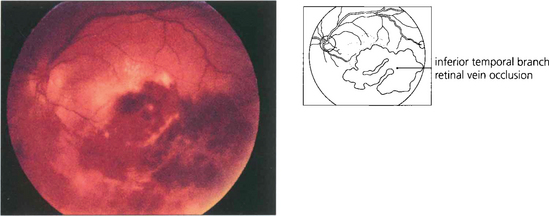

Fig. 10.43 The posterior uveitis of Behçet’s disease may be asymmetrical or even unilateral. There is usually diffuse vascular leakage throughout the fundus; focal periphlebitis (as seen in sarcoidosis) is not a feature of Behçet’s disease. This patient has an inferior branch retinal vein occlusion. Venous occlusion in the presence of posterior uveitis should always suggest the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease.

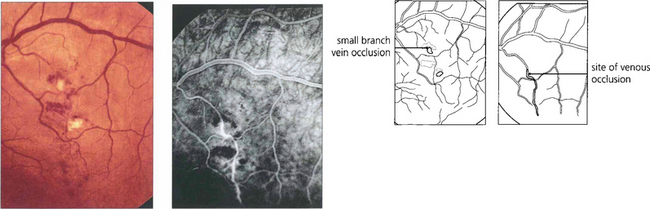

Fig. 10.44 This 33-year-old man presented with a history of oral ulcers and visual loss in his left eye with a mild posterior uveitis. The fluorescein angiogram shows a macular branch vein occlusion occurring along the vessel in the absence of an AV crossing indicating that the occlusion is vasculitic.

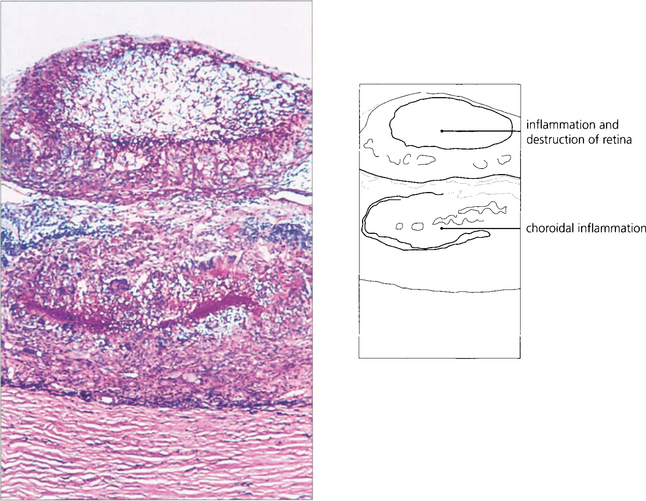

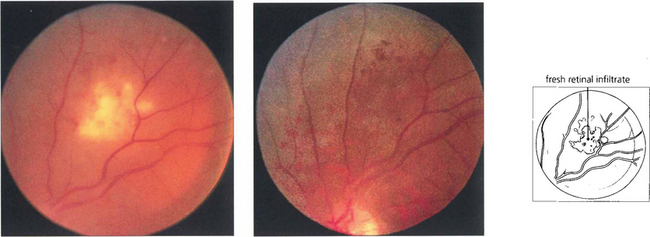

Fig. 10.45 White infiltrates of the inner retina sometimes associated with intraretinal haemorrhage can occur during the active phases of Behçet’s disease. Pathologically these are areas of neutrophils infiltrating the retina. In this patient the infiltrates resolved over a period of 2–3 weeks with treatment leaving the retinal pigment epithelium and retinal vasculature looking undisturbed.

Fig. 10.46 In the terminal phase there is optic atrophy secondary to destruction of the retina and its vasculature. The retinal arteries look like white threads from nonperfusion and gliosis. Although there is some disturbance at the macula, pigmentary changes are comparatively sparse for the severity of the disease.

By courtesy of Dr E M Graham.

INFECTIVE CAUSES OF POSTERIOR UVEITIS

Toxoplasmosis

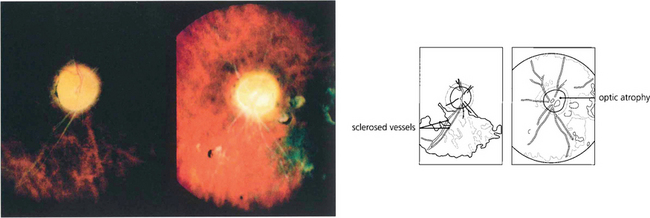

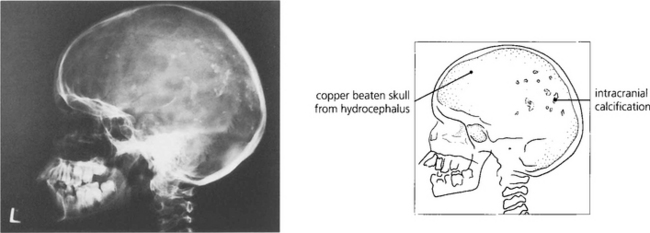

Fig. 10.48 Seroconversion during pregnancy carries a high risk of fetal damage, particularly in the first trimester, but it is exceptional for visual acuity to be lost in both eyes. Severe intracranial infection in a fetus can produce intracranial calcification, hydrocephalus, intellectual impairment and epilepsy.

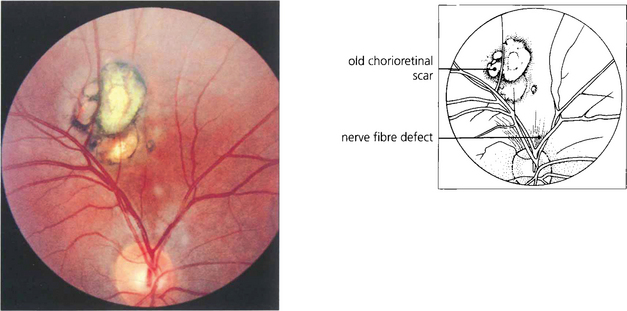

Fig. 10.49 This is a typical quiescent Toxoplasma scar in the posterior pole. It is sharply circumscribed with retinal hyperpigmentation and pigment epithelial atrophy. Note the associated retinal nerve fibre defect.

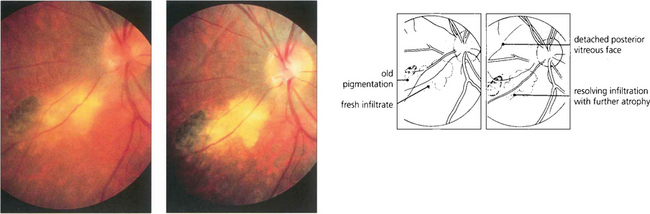

Fig. 10.50 The fellow eye of the same patient as in Fig. 10.49 shows reactivation next to an area of previous scarring. A few weeks later the area of retinal necrosis with inflammatory infiltrate has become more discrete and the vitreous is clearing, leaving further retinal destruction and pigment atrophy. Note the associated posterior vitreous detachment.

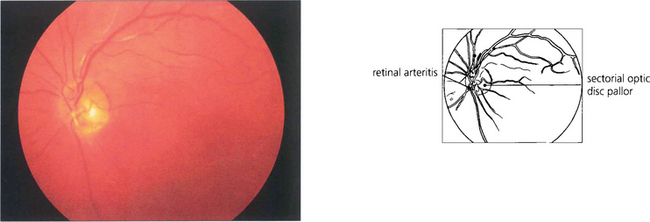

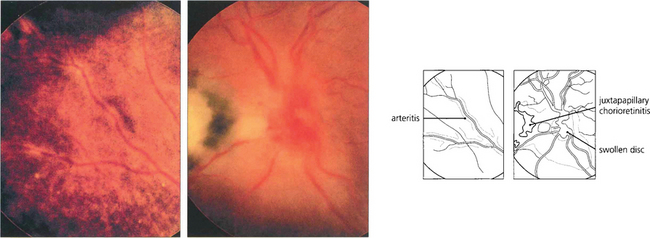

Fig. 10.51 A particular feature of active toxoplasmic chorioretinitis is an arteritis of neighbouring vessels.

Fig. 10.52 Acquired toxoplasmosis is rare. A fresh circumscribed lesion is seen in the fundus with no evidence of previous scarring or pigmentation. The patient had a systemic febrile illness with lymphadenopathy. IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma were found in the blood.

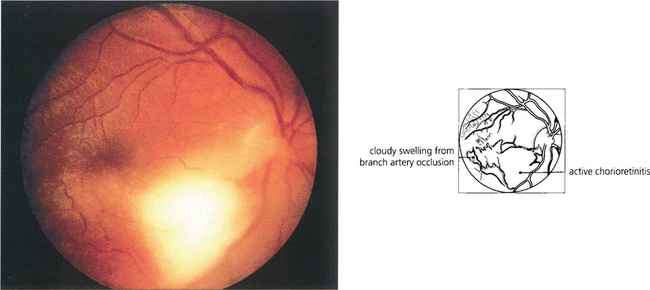

Fig. 10.53 The pathology of toxoplasmosis is primarily retinal necrosis with secondary choroidal changes. After infection the organism remains encysted and intracellular in the retina as inactive bradyzoites (left) for many years. At some stage, for unknown reasons, the cyst ruptures to release the active tachyzoites (right). These proliferate to cause a necrotic retinitis before encysting again.

Left figure by courtesy of Mr C Pavesio.

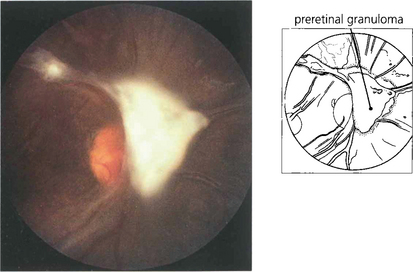

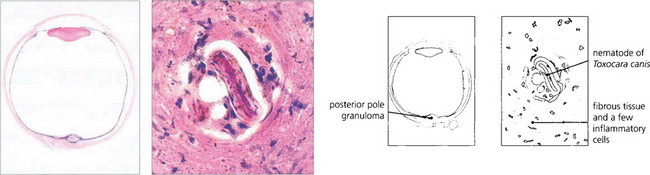

Toxocariasis

Syphilis

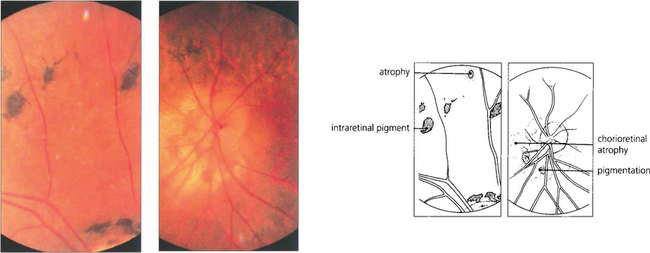

Syphilis during pregnancy infects the fetus and produces a retinopathy. Active lesions are rarely seen in the neonate but are said to be focal, yellowish, spotty retinal pigment epithelial changes associated with vasculitis. This resolves to leave pigmentary scarring with areas of focal pigmentation and atrophy in the peripheral retina, the so-called ‘pepper and salt’ fundus which can sometimes be confused with retinitis pigmentosa. Following congenital syphilis, interstitial keratitis (see Ch. 6) may appear between the ages of 5 and 25 years. Patients may have other stigmata of infection such as nasal and dental deformities or nerve deafness. Progressive neurological deficit is, however, relatively uncommon.

Fig. 10.56 These photographs show the typical maculopapular rash on the hands from secondary syphilis. Spirochaetes can be found in the lesions by examining their exudate with dark field illumination.

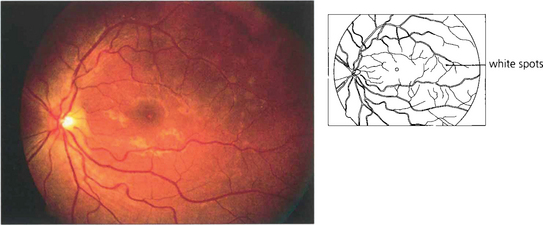

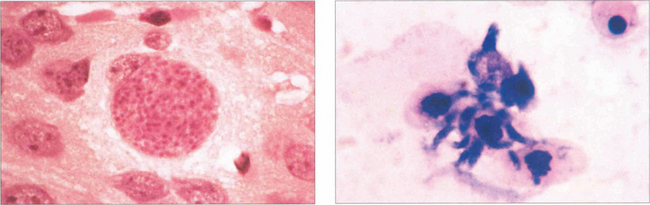

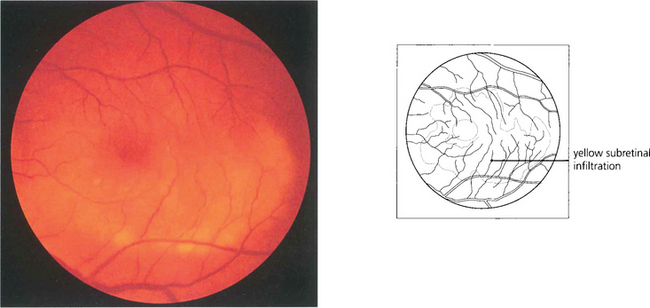

Fig. 10.57 Patients with secondary syphilis usually have a mild posterior uveitis. Widespread yellowish subretinal infiltrates are a common feature and can suggest the diagnosis. This patient was also HIV and hepatitis B positive.

Fig. 10.58 This patient was known to have had congenital syphilis. The optic disc is pale, retinal vessels are attenuated and there is widespread chorioretinal atrophy. The equatorial retina shows large clumps of intraretinal pigmentation. Patients often have good visual function despite their retinopathy. Visual loss is usually due to keratitis and subsequent cataract formation.

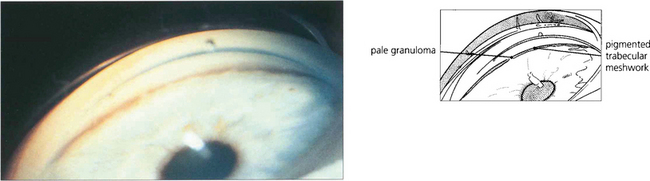

Ocular tuberculosis

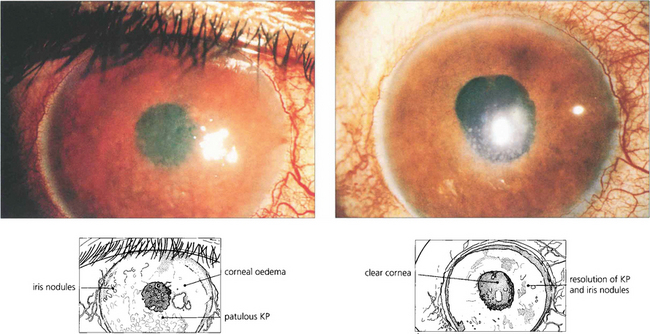

Fig. 10.59 This Pakistani woman had a chronic anterior uveitis with marked nodular involvement of the iris, unresponsive to topical steroid treatment. Chest radiography showed old tuberculous changes and the patient had a strongly positive Mantoux reaction although sputum culture was negative. The iris appearance improved dramatically after 2 weeks of antituberculous chemotherapy.

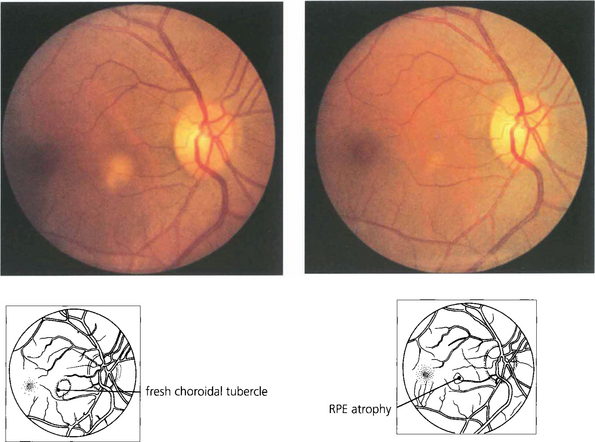

Fig. 10.60 This patient had miliary tuberculosis; a single choroidal tubercule can be seen as a creamy, diffuse, subretinal swelling. Nonspecific pigment epithelial scarring remains after appropriate chemotherapy. Choroidal tubercles are frequently bilateral and multifocal.

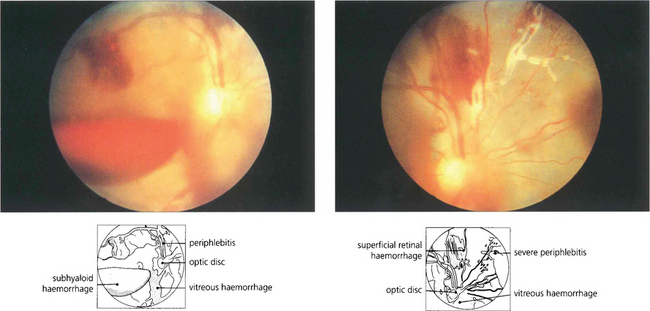

Fig. 10.61 Florid retinal vasculitis can be associated with tuberculosis, especially in Asiatic patients. Posterior uveitis is relatively mild but retinal vasculitis is marked and there is vascular closure and haemorrhage which frequently progresses to neovascularization. The fluorescein angiogram showed peripheral closure with early new vessels and patchy leakage.

Acute retinal necrosis

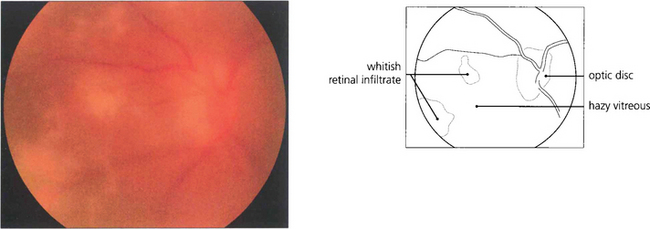

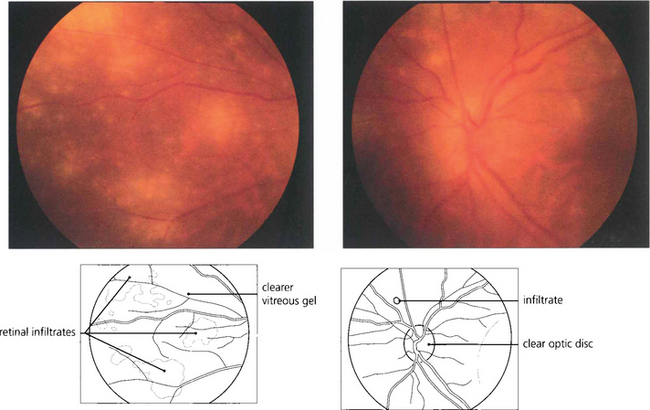

Fig. 10.62 Acute retinal necrosis. This otherwise fit 56-year-old man presented with blurred vision in his left eye of 5 days’ duration. The fundal view is very hazy because of the vitreous infiltrate but patchy white retinal infiltrates can be discerned nasal to the disc.

Fig. 10.63 Vitreous biopsy was positive for herpes zoster on PCR. After 5 days of intravenous antiviral treatment the retinal appearances are clearing and the infiltrates can be seen more clearly.

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)

HIV-associated diseases should be considered in any patient with uveitis with social risk factors, from a high prevalence area or with unusual or atypical uveitis. Both Kaposi’s sarcoma (see Ch. 3) and herpes zoster (see Ch. 4) can affect the anterior segment. Idiopathic cotton wool spots may be seen in a number of cases as transient lesions that disappear spontaneously within 6–8 weeks. The commonest form of retinal infection is cytomegalovirus retinitis although this has become less common with the success of highly active antiretroviral (HAART) therapy. Cyto-megalovirus retinitis is associated with CD4 counts of less than 50 and is uncommon if the count is over 100. Untreated the retinopathy progresses slowly. Both eyes become involved and the lesions relentlessly increase in area with the central part of the lesion becoming atrophic. The retina is destroyed within 6 months. Retinal detachment is common.

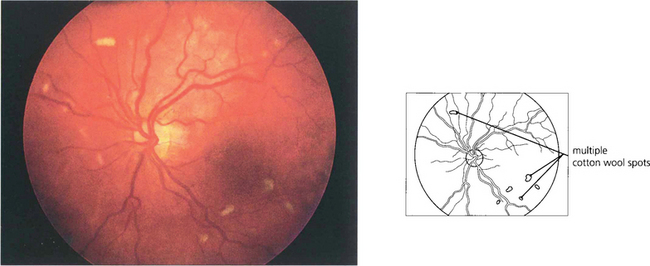

Fig. 10.66 HIV retinopathy is the most common form of ocular involvement in patients with AIDS and is seen in more than 50 per cent of patients prior to HAART. Cottonwool spots are seen in the posterior pole; they are asymptomatic and resolve over 4–6 weeks. They are thought to be caused by HIV infection of retinal vascular endothelium causing microinfarction.

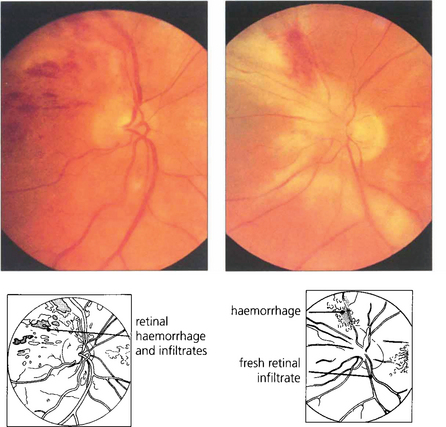

Fig. 10.67 This 46-year-old man presented with poor vision in his left eye. Examination showed a macular lesion with a peripheral lesion typical of cytomegalovirus retinitis. There are creamy areas of retinal necrosis and haemorrhage alongside retinal vessels with a minimal vitreous cellular infiltrate.

Fig. 10.68 The patient was treated with ganciclovir and the lesions improved, but relapsed 3 months later when he discontinued treatment. This led to further retinal destruction and involvement of the fellow eye.

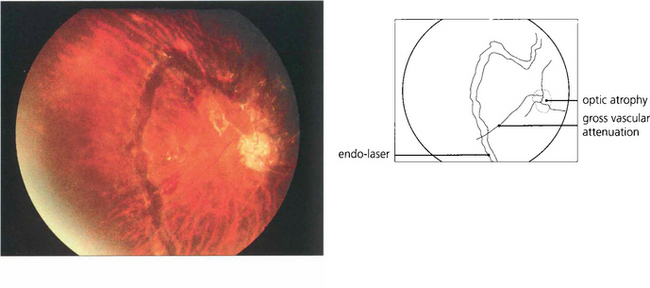

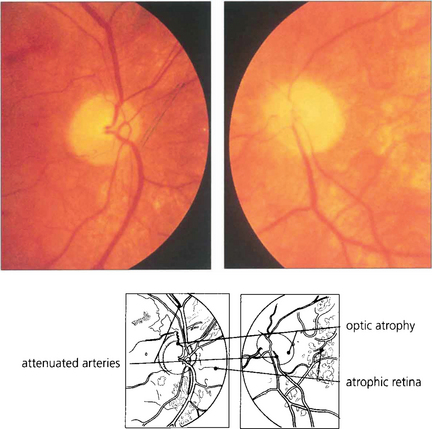

Fig. 10.69 The patient responded to another course of ganciclovir and continued to take maintenance therapy. At this stage the fundi are quiescent with areas of retinal atrophy, pallor of the optic discs and vascular attenuation.

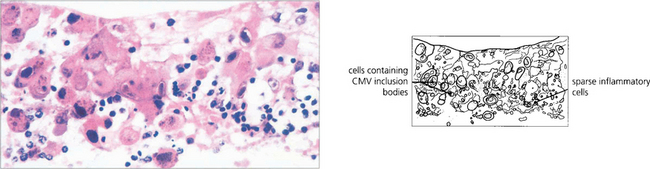

Fig. 10.70 Pathological examination of the same patient shows areas of complete retinal destruction with a sparse inflammatory cellular infiltrate and the typical ‘owl’s eye’ intracellular inclusions of cytomegalovirus.

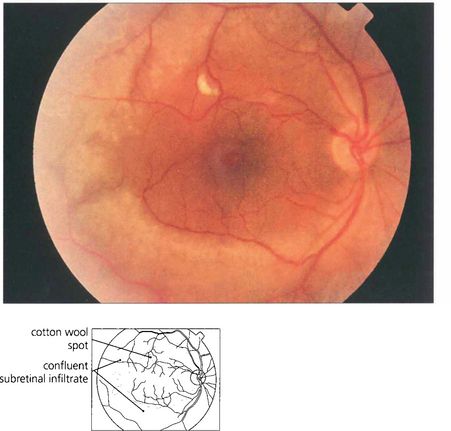

Fig. 10.71 Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) is a multifocal form of herpes zoster retinitis seen in patients with AIDS with very low CD4 counts. It is usually bilateral with minimal signs of ocular inflammation. The deep retinal lesions rapidly become confluent with total visual loss.

By courtesy of Dr P McCluskey.

Fig. 10.72 Choroidal pneumocystis is characterized by multiple subretinal plaques 1–3 disc diameters in size in the posterior pole. The lesions slowly enlarge in the absence of inflammation. Vision is usually good. The ocular lesions are an early sign of life-threatening systemic infection.

By courtesy of Dr E M Graham.

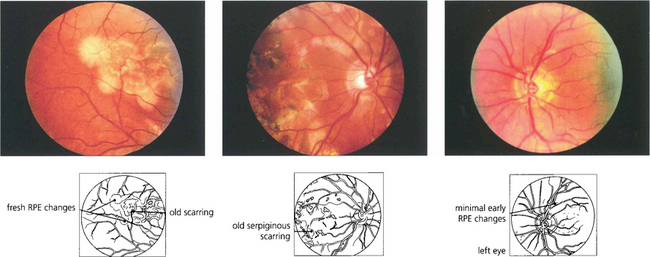

WHITE DOT SYNDROMES

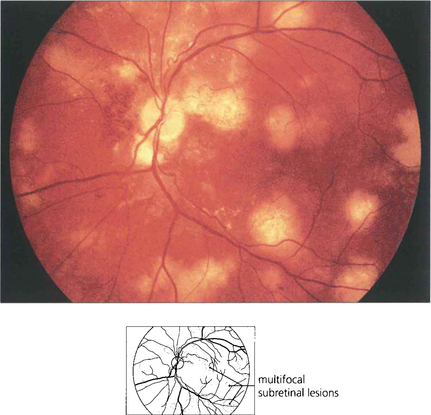

ACUTE MULTIFOCAL PLACOID PIGMENT EPITHELIOPATHY (AMPPE)

Fig. 10.74 Acute placoid lesions are seen as typical creamy white subretinal lesions about one-quarter to one-half a disc in diameter and scattered throughout the posterior pole with some early pigmentary changes. Serous retinal detachment may be present in the acute stage.

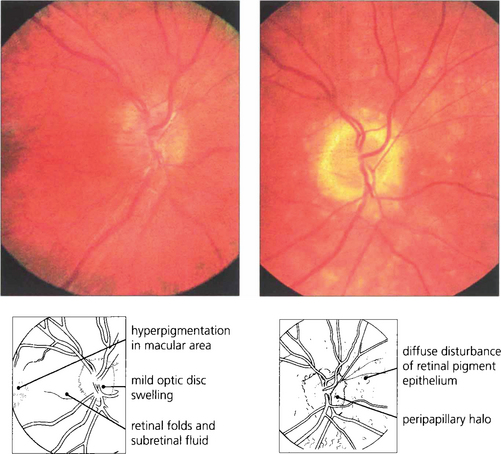

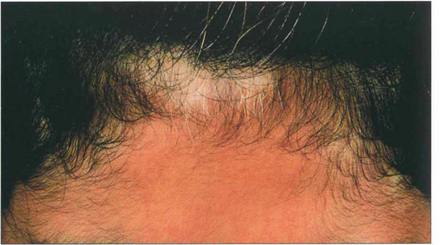

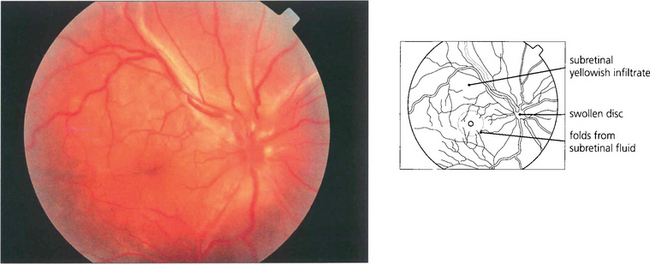

VOGT–KOYANAGI–HARADA (VKH) SYNDROME

Fig. 10.77 This 13-year-old Arab girl presented with a 2-week febrile illness, severe headache and hearing disturbances and then developed a severe bilateral posterior uveitis. Three months later she has greying hair and vitiligo on her forehead.

Fig. 10.79 In the acute phase, fundus examination shows exudative retinal detachment with optic disc oedema. Yellowish mottled lesions can be seen at the level of the RPE.

By courtesy of Dr P McCluskey.

Fig. 10.80 In this patient there is shallow subretinal fluid and disc swelling with subtle yellowish RPE changes. Fluorescein angiography shows multiple areas of pinpoint leakage through the RPE corresponding to some of these lesions. Pooling of dye in the subretinal space can be seen in the fellow eye in the late phase. Similar angiographic changes can be seen with posterior scleritis.

By courtsey of Dr P McCluskey.

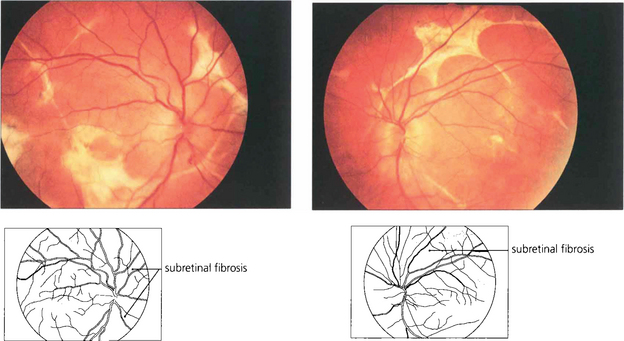

SYMPATHETIC OPHTHALMITIS

The length of the latent interval between perforation and inflammation of the noninjured or sympathizing eye is very variable. Frequently the exciting eye never completely settles down after the injury but sympathetic ophthalmitis can follow a completely quiet eye. About 65 per cent of cases present within 2 weeks to 3 months of the original injury and the majority have occurred within 2 years, although a few cases have been reported to occur many years later.

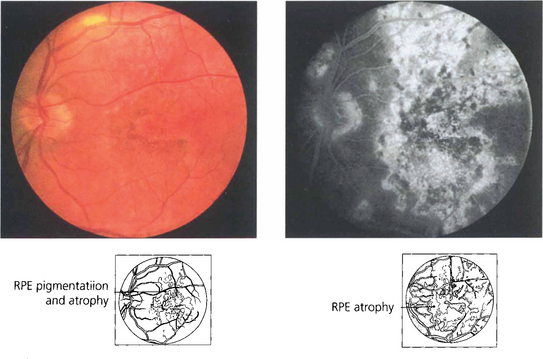

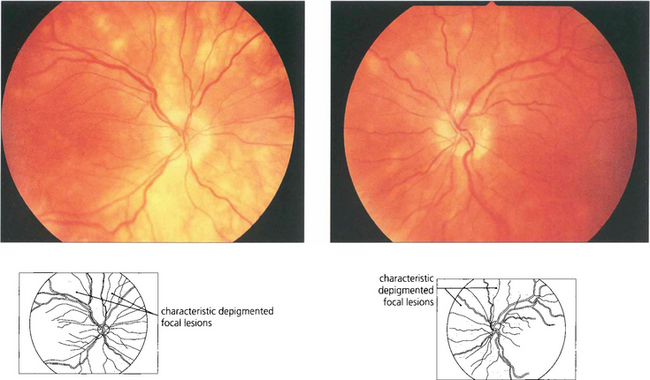

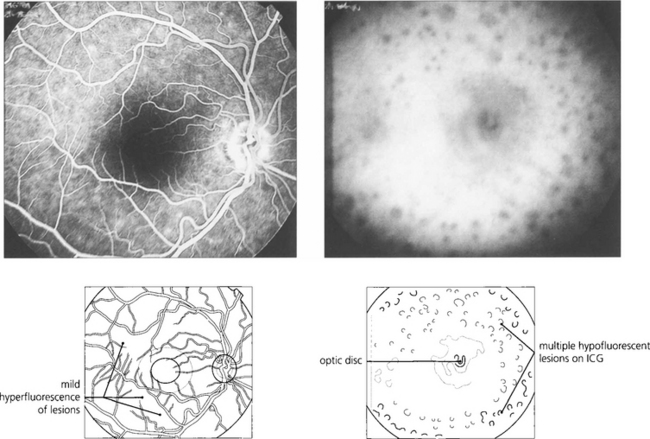

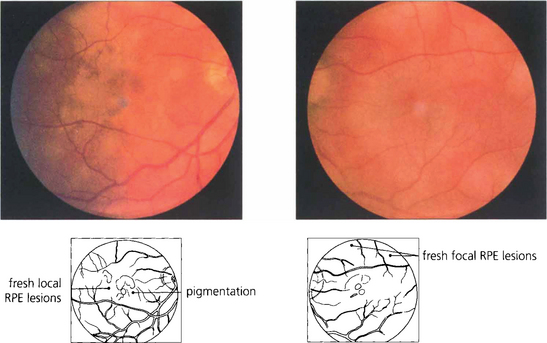

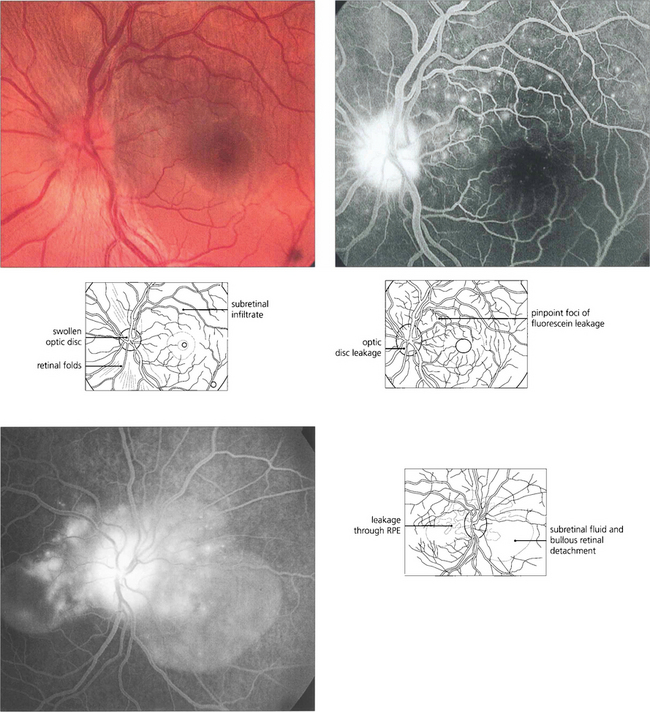

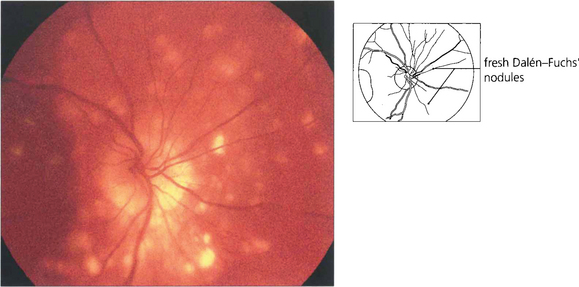

Fig. 10.83 This 63-year-old man developed sympathetic ophthalmitis 3 years after a perforating injury and multiple surgical procedures to the left eye and presented with blurred vision, floaters and panuveitis. Fundus examination shows multiple focal areas of RPE depigmentation at the site of Dalen–Fuchs’ nodules. Fresh lesions have a fluffy creamy appearance; older lesions are whiter and more demarcated with RPE atrophy. Fluorescein angiography shows leakage from the optic disc, cystoid macular oedema, hyperfluorescence from the fresh lesions and window defects in the atrophic lesions.

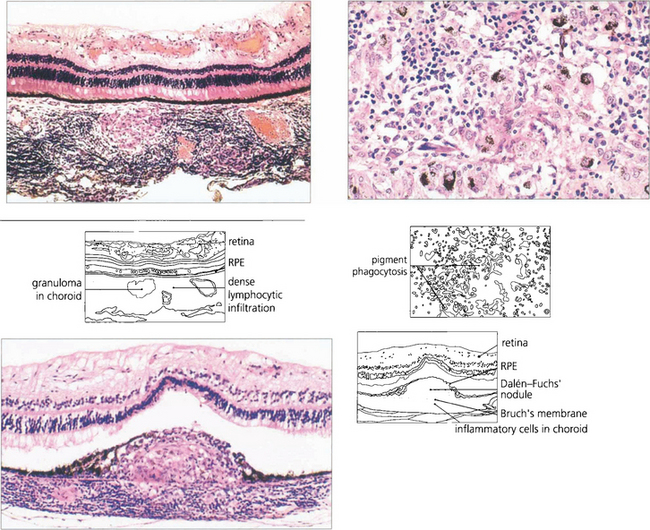

Fig. 10.84 Histologically, in sympathetic ophthalmitis lymphocytes (initially CD4 cells, later CD8 cells) infiltrate the uvea. (Top left) Lymphocytic infiltration with granuloma formation in the choroid. (Top right) Pigment phagocytosis by epithelioid cells. (Bottom left) Dalen–Fuchs’ nodule (i.e. a granuloma between Bruch’s membrane and the RPE).

BIRDSHOT CHORIORETINOPATHY

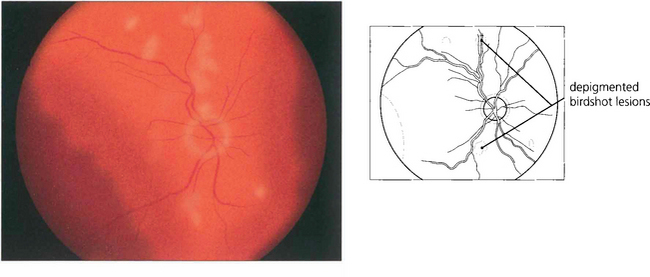

Fig. 10.86 There is mild disc swelling with multiple areas of depigmentation one-third to one-half a disc in diameter throughout the posterior pole. A feature of note is that these areas are never associated with any pigmentation.

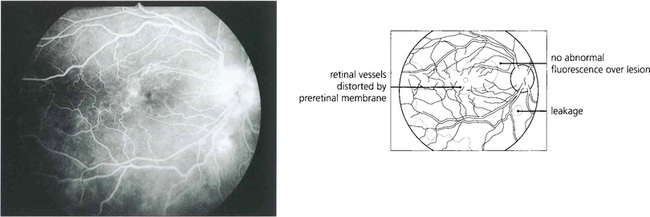

MASQUERADE SYNDROMES

OCULAR LYMPHOMA

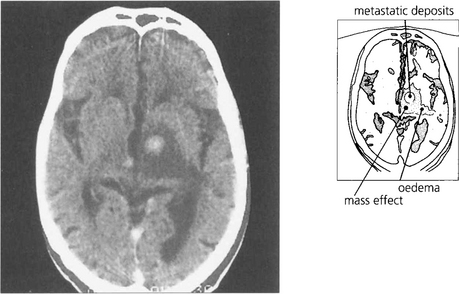

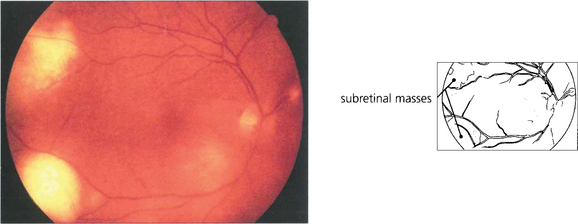

Fig. 10.91 This patient presented with posterior uveitis and subretinal infiltrates. He was treated with systemic steroids but the ocular signs continued to deteriorate.

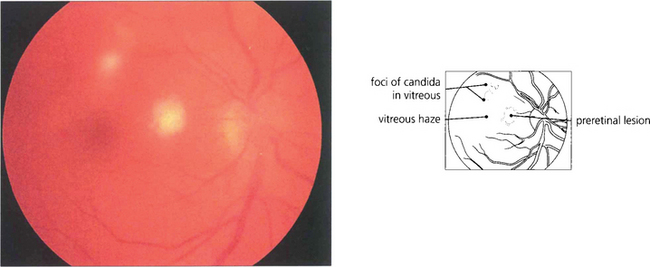

OCULAR CANDIDIASIS

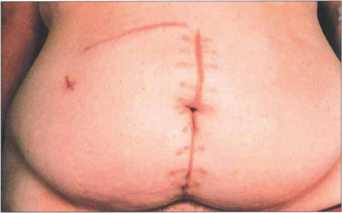

Fig. 10.94 This patient developed bilateral candida endophthalmitis after intensive care with prolonged intravenous feeding following multiple abdominal surgical procedures.