Intracranial pressure

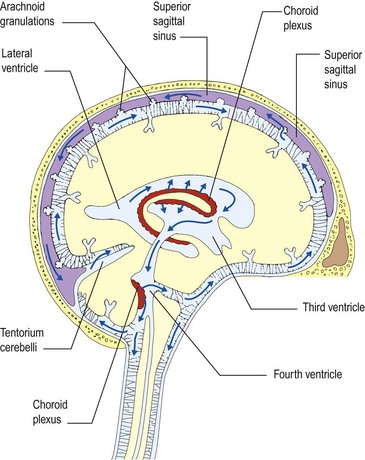

Before considering coma and unconsciousness it is useful to understand intracranial pressure and brain herniation. The intracranial compartment is a fixed box containing brain, blood and CSF. The dynamics of CSF flow are illustrated in Figure 1. Pressure may be increased by:

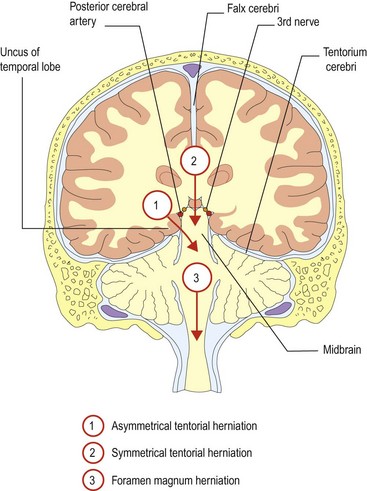

There are two semi-rigid sheets, the falx cerebri and the tentorium cerebelli, which almost divide the brain into separate compartments with relatively small apertures between them (Fig. 2). When the pressure rises in one compartment, the brain may herniate through the apertures into adjacent compartments. The cerebellar tonsils and fourth ventricle may also be forced down through the foramen magnum. These are life-threatening complications that further block CSF flow, causing a vicious circle of rising intracranial pressure, resulting in coma (see below).

In some circumstances, such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), previously called benign intracranial hypertension (BIH), no cause may be found (p. 40).

Raised intracranial pressure

In children who develop raised intracranial pressure, usually a result of hydrocephalus, before closure of the skull sutures, presentation may be with a rapidly enlarging head size and minimal neurological compromise.

Low intracranial pressure

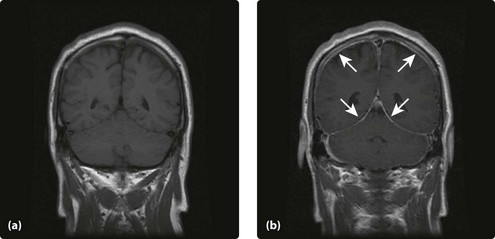

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension is being recognized increasingly. Patients present with generalized headaches, that at least initially are posturally triggered, getting worse on standing and improving on lying flat. They may develop false localizing signs such as 6th nerve palsies. MRI scanning with gadolinium demonstrates marked dural enhancement reflecting engorged normal veins (Fig. 3). The CSF volume is reduced so the veins enlarge and the skull is a a fixed volume ‘box’. The condition is often self-limiting, but may improve with blood patching (p. 39).

Herniation

There are two major sites of cerebral herniation.

The tentorium

Here the brain herniates through the space between the cerebrum and the cerebellum surrounded by the tentorium cerebri (see Fig. 2). This can be symmetrical or asymmetrical. Asymmetrical is more common. The uncus of the temporal lobe is squeezed through this space. This compresses:

Treatment

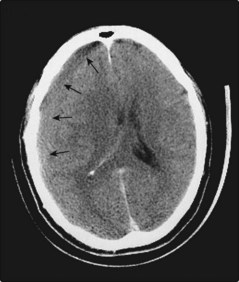

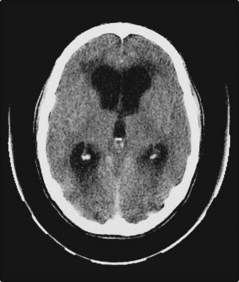

Treatment will depend on the cause. There may be readily treatable surgical causes, such as subdural (Fig. 4) or extradural haematoma, or hydrocephalus (Fig. 5). These would be treated with drainage or shunting.