Chapter 60 Intracapsular Femoral Neck Fracture: How Does Delay in Surgery Affect Complication Rate?

Speed1 termed the displaced intracapsular femoral neck fracture the unsolved fracture because of its high rate of complications and controversies in management at the time. Many years later, this fracture continues to challenge the treating orthopedic surgeon. Much of the difficulty lies in the precarious blood supply to the femoral neck and head. This leads to the two most common and devastating orthopedic complications: nonunion and avascular necrosis of the femoral head. These fractures have long been believed to represent an orthopedic emergency, requiring immediate intervention to prevent these complications. Displaced femoral neck fractures occur infrequently (only 3% of all hip fractures) in the young adult (i.e., younger than 60 years); therefore, it is difficult to obtain adequate power to conduct a study to determine whether timing of intervention actually impacts the rate of complications.2,3 This fracture occurs much more frequently in the elderly population; however, epidemiology, mechanism of injury, rates of complications, and treatment options are different for this age group. This chapter examines the effect of time to surgery on complication rates for displaced femoral neck fractures in these two age groups.

OPTIONS

Displaced femoral neck fractures in the young adult patient tend to result from high-energy trauma. Typically, this produces a highly unstable vertical shear fracture and is often associated with other injuries (e.g., ipsilateral femoral shaft fracture).3–5 This high-energy mechanism may also result in significant injury to the soft tissues surrounding the hip joint. Cadaveric injection studies and radioisotope scans of the femoral head show that there are both intraosseous and extraosseous vessels supplying the femoral head and neck.6,7 The major extraosseous blood supply to the femoral head comes from the medial femoral circumflex artery and its retinacular branches (inferior, posterior, and superior). The artery of the ligamentum teres supplies a negligible volume of the femoral head in most of the population. In displaced femoral neck fractures, blood supply to the femoral head and neck is mainly dependant on the extraosseous retinacular branches of the medial femoral circumflex. Several questions become apparent: Does nonunion and avascular necrosis depend on the extent of damage to these vessels at the time of injury and not the time from injury to operative fixation in high-energy injuries? Do high-energy injuries have greater rates of nonunion and avascular necrosis than low-energy injuries?

Several authors have discussed the possibility that avascular necrosis of the femoral head is related to increased intracapsular pressure.8,9 Increased intracapsular pressure may result in occlusion of the retinacular vessels. This has often been the argument for early surgical intervention or aspiration to “decompress” the hip capsule. Are rates of avascular necrosis affected by hip capsule decompression?

Low-energy injuries may occur in the young adult. Robinson and colleagues3 and Swiontkowski and coauthors4 comment on a subgroup of patients from this population who have longstanding medical problems and sustain this fracture from a simple fall. They found that these patients tended to have an increased prevalence of alcoholism, arthritis, cardiorespiratory problems, neuromuscular disorders, and epilepsy. Is this subgroup of patients best grouped with elderly patients because their fractures likely occur secondary to osteoporosis and result from low-energy trauma?

Displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly have been examined mainly from the standpoint of treatment. A lack of agreement remains among surgeons regarding optimal treatment (internal fixation vs. arthroplasty) for those fractures in the young elderly group (i.e., 60–80 years of age).10 Internal fixation of the fracture in this age group has several advantages compared with arthroplasty: shorter operative time, decreased blood loss, and reduced perioperative mortality.11 Many of these patients have significant comorbidities and require medical management before surgery. Does time from injury to surgery affect the rates of nonunion and avascular necrosis in elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures?

EVIDENCE

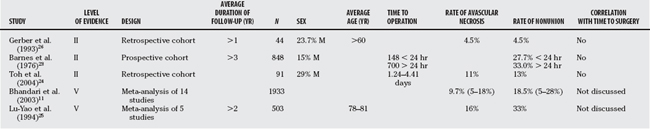

Damany and coauthors2 reported a meta-analysis on intracapsular femoral neck fractures in the young adult (15–50 years of age). This is Level II evidence because they incorporated the results of 18 retrospective cohort studies (547 fractures) published between 1976 and 2003. They found that displaced femoral neck fractures occurred more frequently than nondisplaced fractures (79.9% vs. 25.6%) in this age group. The overall rate of avascular necrosis for the displaced fractures was 22.5%, and the rate of nonunion was 6.0%. They identified 7 studies (170 fractures) that gave data regarding timing of surgery and development of complications. From their analysis of these data, they found no significant difference in the rate of avascular necrosis for fractures reduced within 12 hours of injury (13.6%) as compared with those reduced after 12 hours (15%) of injury. Similarly, there was no difference in nonunion rates between the 2 groups (11.8% before 12 hours and 5.0% after 12 hours). This study represents the best evidence on timing of surgery and complications for displaced femoral neck fractures (Table 60-1).

TABLE 60-1 Studies That Examine Correlation of Complication Rates with Time from Injury to Surgery for Young Adults

Upadhyay and investigators’12 Level II study found no evidence of decreased complication rates with early intervention among 92 young adults with displaced femoral neck fractures. Rates of avascular necrosis were 14% in the group treated within 48 hours of injury and 19% in the group treated over 48 hours after injury. The nonunion rate was 18% in the early treatment group and 16.7% in the delayed group. Haidukewych and colleagues’13 Level IV study also found no association between operative delay and complication rates.

Several Level II studies included in the meta-analysis by Damany and coauthors2 conclude that the time interval between injury and surgery does affect complication rates. Swiontkowski and coauthors4 conclude that their good results (no nonunions and 20% rate of avascular necrosis) were due to early intervention. However, their sample size was small (21 patients) and included 4 nondisplaced fractures and only 1 displaced fracture treated over 12 hours after injury. Jain and colleagues14 found a significantly greater rate of avascular necrosis in patients treated 12 hours after injury (none in those treated before 12 hours and 26% after 12 hours). This study also had a small sample size (38 patients), 9 patients in the study had nondisplaced fractures, and only 7 patients in the early treatment group were followed for more than 2 years radiographically. Radiographic follow-up of more than 2 years is often suggested because approximately 20% of avascular necrosis cases present more than 2 years after injury.7

Two case series from the developing world give rates of avascular necrosis for neglected displaced femoral neck fractures in the young adult. Huang15 found a rate of avascular necrosis of 25% for patients with displaced fractures seen for nonunion from 3 months to 2 years after injury. Roshan and Ram16 treated 32 patients treated at 12 to 30 weeks after injury and recorded no cases of avascular necrosis after at least 2 years of follow-up. Both these studies conclude that avascular necrosis was not related to timing of surgery, given that the results were equal to or better than fractures fixed on an urgent basis.

Studies have examined the vascularity of femoral heads retrieved from patients undergoing arthroplasty within 2 weeks after sustaining a displaced femoral neck fracture. Calandruccio and Anderson7 report that 22% of femoral heads were vascular, 47% were partially avascular, and 32% were avascular. Similarly, Catto17 found that 17% of femoral heads were vascular, 50% were partially avascular, and 33% were avascular. These studies suggest that at the time of fracture, the majority of femoral heads (i.e., 79–83%) are at least partially avascular. Because reported rates of avascular necrosis are less than 30% (even with delayed fixation), there are two possible scenarios: (1) the femoral head undergoes revascularization with time, or (2) some patients have asymptomatic avascular necrosis without segmental collapse of the head. Calandruccio and Anderson7 suggest that the latter was true, and that the fate of the femoral head was determined at the time of injury. We agree with this statement and believe that the vascularity of the femoral head is largely dependent on the degree of the initial injury.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Should the Intracapsular Hematoma Be Decompressed?

In young patients with displaced femoral neck fractures, time from injury to treatment does not appear to have a significant effect on avascular necrosis rates. This suggests that the fate of the femoral head is determined at the time of injury. Furthermore, decompression of the capsule (either through open reduction or aspiration) has not been shown clinically to affect development of avascular necrosis. Maruenda and coauthors’18 Level I study showed no relation between intracapsular pressure (pressure above diastolic pressure) and development of avascular necrosis or reduction in blood supply to the femoral head (measured by the scintigraphy ratio). This study also included nondisplaced fractures and found no difference in intracapsular pressures between nondisplaced and displaced fractures with the leg in a resting position.

Upadhyay and investigators12 also found no significant difference in rates of avascular necrosis and nonunion for displaced fractures treated with closed reduction and pinning compared with those treated with open reduction, capsulotomy, and pinning. This study found that quality of reduction, quality of fixation, and posterior comminution all influenced the rates of this complication. Posterior comminution has been cited by several as a poor prognostic indicator.19–21 Posterior comminution may indicate significant damage to the posterior retinacular vessels (main blood supply to the femoral head) or may influence the ability to obtain a good quality reduction. Poor reduction, especially varus angulation, has also been cited by several authors as a factor for failure of fixation and development of nonunion.12,20–22 Chua and coworkers22 conducted a retrospective cohort study on 108 elderly patients with femoral neck fractures and found that difficulty in obtaining a reduction was associated with a significantly greater rate of failure of fixation (4.3 times).22 If the reduction was difficult to obtain and the hip was fixed in varus, then the fixation was 13.6 times more likely not to be successful.

Displaced femoral neck fractures occur infrequently in the young adult population, and this has made clinical study of this fracture challenging. Studies in the literature have small sample sizes, require many years to obtain appropriate sample numbers, combine results from multiple surgeons and hospitals, and incorporate different methods of fixation. This makes interpretation of results difficult. Based on the results from Damany and coauthors’2 meta-analysis (avascular necrosis rate of 13.6% and nonunion rate of 11.8% for fractures fixed within 12 hours), we calculated the sample size required to detect a difference in these complication rates between equal groups of fractures fixed within 12 hours and more than 12 hours after injury. Assuming a relative risk ratio of 2 (rate of complications is twice as frequent in the group of fractures fixed after 12 hours), these calculations suggest that at least 270 patients would be required to determine a significant difference (α = 0.05; β = 0.8). (The actual relative risk ratio is likely less than 2, indicating that an even larger sample size is required.) No retrospective case-controlled studies in the literature have this sample size.

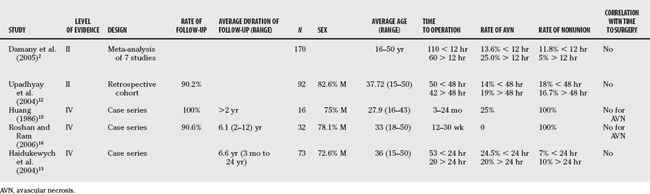

Studies on displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly population have similar difficulties (Table 60-2). Although this fracture is much more common in this age group, many surgeons elect to replace the femoral head rather than attempt to save it. This also leads to relatively small sample sizes. As a result, we have had to rely on meta-analyses to extract data from the literature. Based on our review of the literature, we have made the following recommendations (Table 60-3):

TABLE 60-3 Grades of Evidence for Displaced Intracapsular Femoral Neck Fractures

| RECOMMENDATIONS | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

1 Speed K. The unsolved fracture. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1935;60:341.

2 Damany DS, Parker MJ, Chojnowski A. Complications after intracapsular hip fractures in young adults. A meta-analysis of 18 published studies involving 564 fractures. Injury. 2005;36:131-141.

3 Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, et al. Hip fractures in adults younger than 50 years of age: Epidemiology and results. Clin Orthop. 1995;312:238-246.

4 Swiontkowski MF, Winquist RA, Hansen SH. Fractures of the femoral neck in patients between the ages of twelve and forty-nine years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66-A:837-846.

5 Swiontkowski MF, Hansen ST, Kellam J. Ipsilatera1 fracture of the femoral neck and shaft. A treatment protocol. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66-A:260-268.

6 Sevitt S, Thompson RG. The distribution and anastomoses of arteries supplying the head and neck of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47-B:560-573.

7 Calandruccio RA, Anderson WE. Post-fracture avascular necrosis of the femoral head: Correlation of experimental and clinical studies. Clin Orthop. 1980;152:49-84.

8 Soto-Hall R, Johnson LH, Johnson R. Alterations in the intra-articular pressures in transcervical fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;46-A:662.

9 Bonnaire F, Schaefer DJ, Kuner EH. Hemarthrosis and hip joint pressure in femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop. 1998;353:148-155.

10 Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Tornetta P, et al. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. An international survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87-A:2122-2130.

11 Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, et al. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1673-1681.

12 Upadhyay A, Jain P, Mishra P, et al. Delayed internal fixation of fractures of the neck of the femur in young adults. A prospective, randomised study comparing closed and open reduction. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86-B:1035-1040.

13 Haidukewych GJ, Rothwell WS, Jacofsky DJ, et al. Operative treatment of femoral neck fractures in patients between the ages of fifteen and fifty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1711-1716.

14 Jain R, Koo M, Kreder HJ, et al. Comparison of early and delayed fixation of subcapital fractures in patients sixty years of age or less. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1605-1612.

15 Huang CH. Treatment of neglected femoral neck fractures in young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;206:117-126.

16 Roshan A, Ram S. Early return to function in young adults with neglected femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:152-157.

17 Catto M. A histological study of avascular necrosis of the femoral head after transcervical fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47-B:749.

18 Maruenda JI, Barrios C, Gomar-Sancho F. Intracapsular hip pressure after femoral neck fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;340:172-180.

19 Scheck M. Intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck: Comminution of the posterior neck cortex as a case of unstable fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41-A:1187-1200.

20 Asnis SE, Wanek-Sgaglione L. Intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck: Results of cannulated screw fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76-A:1793-1803.

21 Bray TJ. Femoral neck fracture fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 339; 1997; 20-31.

22 Chua D, Jaglal SB, Schatzker J. Predictors of early failure of fixation in the treatment of displaced subcapital hip fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:230-234.

23 Barnes R, Brown JT, Garden RS, Nicoll EA. Subcapital fractures of the femur. A prospective review. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58-B:2-24.

24 Toh EM, Sahni V, Acharya A, et al. Management of intracapsular femoral neck fractures in the elderly; is it time to rethink our strategy? Injury. 2004;35:125-129.

25 Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, et al. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76-A:15-25.

26 Gerber C, Strehle J, Ganz R. The treatment of fractures of the femoral neck. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;292:77-86.