Intra-cardiac Masses and Devices

Al Solina, F. Luke Aldo and Salvatore Zisa

Cardiac Masses: A mass by any other name, is still a mass. Or is it?

You may remember from high school physics that mass is simply a quantity of matter. Under the right set of circumstances, it can even be converted into a predictable amount of energy. But that’s not what we are talking about here. Cardiac masses come in a variety of shapes, sizes, locations, consistencies, and clinical significance. They can be characterized primarily into real masses, and normal anatomical structures that masquerade as masses. Real cardiac masses can be further characterized as being benign or malignant, and as being primary or metastatic. In order to differentiate between these possibilities it is important to understand normal anatomy, the physics involved with imaging artifacts (see Chapter 5), and the characterization of real cardiac masses. Echocardiography has been utilized to image cardiac masses since the 1950s, and can be used to characterize the anatomy and pathophysiological consequences of the mass. Although a mass may be histologically benign, it may muck up the normal function of the heart by interfering with chamber filling or valve function, and therefore not be benign from a physiological perspective.

Masses that are Not Really Masses

Atrial Anatomic Variants

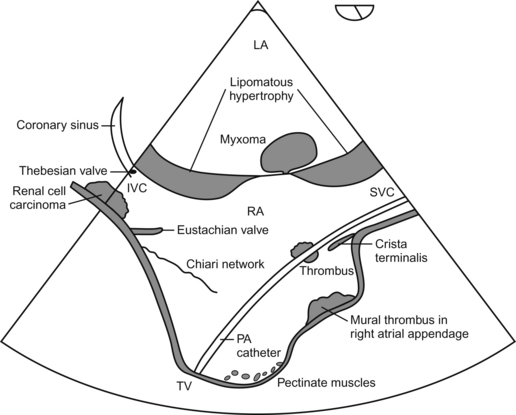

Chiari network—having little to do with communications or information technology, this network is a filamentous embryological remnant located in the RA.

Chiari network—having little to do with communications or information technology, this network is a filamentous embryological remnant located in the RA.

Coumadin ridge—a finger-like projection of tissue in the LA, which separates the left superior pulmonary vein from the left atrial appendage. It is sometimes mistaken for a thrombus.

Coumadin ridge—a finger-like projection of tissue in the LA, which separates the left superior pulmonary vein from the left atrial appendage. It is sometimes mistaken for a thrombus.

Crista terminalis—not a train station in Rome, but rather a ridge of tissue in the RA located at the junction of the SVC and the RA appendage.

Crista terminalis—not a train station in Rome, but rather a ridge of tissue in the RA located at the junction of the SVC and the RA appendage.

Eustachian valve—an embryological remnant, located at the junction between the IVC and the RA, and directed towards the fossa ovalis of the interatrial septum.

Eustachian valve—an embryological remnant, located at the junction between the IVC and the RA, and directed towards the fossa ovalis of the interatrial septum.

Foreign bodies—pacemaker and AICD leads, catheters, and cannulae of all different flavors may parade around in the atria. Additionally they may cause reverberations and side lobe artifacts that further muddle things up.

Foreign bodies—pacemaker and AICD leads, catheters, and cannulae of all different flavors may parade around in the atria. Additionally they may cause reverberations and side lobe artifacts that further muddle things up.

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum—this benign variant is characterized by a sometimes dramatic thickening of adipose tissue surrounding, but sparing the fossa ovalis of the interatrial septum. It kind of looks like a dumbbell. Thick-thin-thick. While not having any meaningful significance in terms of acute pathophysiological consequence, it is easy to recognize and very impressive to say.

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum—this benign variant is characterized by a sometimes dramatic thickening of adipose tissue surrounding, but sparing the fossa ovalis of the interatrial septum. It kind of looks like a dumbbell. Thick-thin-thick. While not having any meaningful significance in terms of acute pathophysiological consequence, it is easy to recognize and very impressive to say.

Ventricular Anatomic Variants

False chords—nothing false about them. They are real anatomic structures. They are typically thin, well…chords running across the LV, near the apex.

False chords—nothing false about them. They are real anatomic structures. They are typically thin, well…chords running across the LV, near the apex.

Papillary muscles—hard to confuse these for anything abnormal if you know their standard anatomical location, and the fact that they have the appearance of myocardium. These muscles are found anterolaterally and posteromedially in the LV, and attach to the mitral valve via the chordae tendinae.

Papillary muscles—hard to confuse these for anything abnormal if you know their standard anatomical location, and the fact that they have the appearance of myocardium. These muscles are found anterolaterally and posteromedially in the LV, and attach to the mitral valve via the chordae tendinae.

Trabeculations—muscular ridges, which can be quite prominent, especially in the RV.

Trabeculations—muscular ridges, which can be quite prominent, especially in the RV.

Moderator band—this is not some politically correct hip-hop band, it’s a muscular band of tissue that traverses the apical third of the RV. It can be confused with a thrombus or tumor.

Moderator band—this is not some politically correct hip-hop band, it’s a muscular band of tissue that traverses the apical third of the RV. It can be confused with a thrombus or tumor.

Masses that Really are Masses

“Benign” primary cardiac masses: these masses are “benign” in their tissue characterization, but may misbehave and cause functional disturbances attributable to their anatomical location!

Myxoma—most common primary tumor, seen most frequently in the LA. Can be quite large and interfere with valvular function. Have a non-homogeneous appearance. Female preponderance. May commonly be seen attached to a stalk from the LA side of the interatrial septum. May be associated with systemic embolization.

Myxoma—most common primary tumor, seen most frequently in the LA. Can be quite large and interfere with valvular function. Have a non-homogeneous appearance. Female preponderance. May commonly be seen attached to a stalk from the LA side of the interatrial septum. May be associated with systemic embolization.

Lipoma—second most common benign primary cardiac mass. Usually found in the left ventricle and right atrium, are homogeneous and hyperechoic in appearance. Not associated with systemic embolization. Can be up to 15 cm in size.

Lipoma—second most common benign primary cardiac mass. Usually found in the left ventricle and right atrium, are homogeneous and hyperechoic in appearance. Not associated with systemic embolization. Can be up to 15 cm in size.

Fibroma—second most common benign cardiac tumor in children (rhabdomyoma is first). Most frequently seen in the ventricle. Although benign in tissue type, may be associated with impaired ventricular filling and/or arrythmias.

Fibroma—second most common benign cardiac tumor in children (rhabdomyoma is first). Most frequently seen in the ventricle. Although benign in tissue type, may be associated with impaired ventricular filling and/or arrythmias.

Vegetation—strange name really. Don’t think anyone really considers these little nuggets to be edible. Bacteremic vegetations are usually found in the left heart (except in the case of IV drug abusers), and are usually located on the upstream side of the valve. They can interfere with valve function and may be associated with abcesses. Movement usually synchronized with valve motion as they are attached to it.

Vegetation—strange name really. Don’t think anyone really considers these little nuggets to be edible. Bacteremic vegetations are usually found in the left heart (except in the case of IV drug abusers), and are usually located on the upstream side of the valve. They can interfere with valve function and may be associated with abcesses. Movement usually synchronized with valve motion as they are attached to it.

Papillary fibroelastoma—as the most common primary tumor affecting valves, it resembles a small (<1 cm) vegetation, but is usually seen on the downstream side of a valve. Found more frequently in association with left heart valves in patients greater than 50 years of age. Are sometimes associated with embolic events.

Papillary fibroelastoma—as the most common primary tumor affecting valves, it resembles a small (<1 cm) vegetation, but is usually seen on the downstream side of a valve. Found more frequently in association with left heart valves in patients greater than 50 years of age. Are sometimes associated with embolic events.

Rhabdomyoma—most common tumor in children, usually before one year of age. May obstruct blood flow and can be associated with arrhythmias and heart block. Frequently found in conjunction with tuberous sclerosis.

Rhabdomyoma—most common tumor in children, usually before one year of age. May obstruct blood flow and can be associated with arrhythmias and heart block. Frequently found in conjunction with tuberous sclerosis.

Thrombi—tend to occur in areas of slow blood flow such as the left atrial appendage, LV apex, and ventricular aneurysms. One hint that the blood is slow-moving is when you see slowly swirling streams of blood movement, called “smoke”. Where there is smoke there are thrombi! Thrombi are readily detected in the LA by TEE, but may be more difficult to interrogate and define when they reside in the ventricular apex.

Thrombi—tend to occur in areas of slow blood flow such as the left atrial appendage, LV apex, and ventricular aneurysms. One hint that the blood is slow-moving is when you see slowly swirling streams of blood movement, called “smoke”. Where there is smoke there are thrombi! Thrombi are readily detected in the LA by TEE, but may be more difficult to interrogate and define when they reside in the ventricular apex.

Malignant Primary Cardiac Masses

Angiosarcoma—is the most common primary malignancy of the heart, and displays a fondness for the right atria of middle-aged men. They may be either intracavitary or infiltrative. They are associated with a grave prognosis.

Angiosarcoma—is the most common primary malignancy of the heart, and displays a fondness for the right atria of middle-aged men. They may be either intracavitary or infiltrative. They are associated with a grave prognosis.

Rhabdomyosarcoma—male preponderance. Often multiple lesions, involving any heart chamber. Most common cardiac malignancy in children. May interfere with valve function.

Rhabdomyosarcoma—male preponderance. Often multiple lesions, involving any heart chamber. Most common cardiac malignancy in children. May interfere with valve function.

Mesothelioma—affecting men more often than women, is typically seen between ages 30 and 50.

Mesothelioma—affecting men more often than women, is typically seen between ages 30 and 50.

Schematic Representation of Common Cardiac “Masses”

Metastatic Cardiac Masses

Lung cancer—most common source of metastatic cardiac tumors.

Lung cancer—most common source of metastatic cardiac tumors.

Malignant melanoma displays a particular penchant for spread to the heart.

Malignant melanoma displays a particular penchant for spread to the heart.

Renal cell carcinoma—these puppies may actually grow in to the right atrium, and require cardiopulmonary bypass and even deep hypothermic circulatory arrest to resect. Makes for a complicated day!

Renal cell carcinoma—these puppies may actually grow in to the right atrium, and require cardiopulmonary bypass and even deep hypothermic circulatory arrest to resect. Makes for a complicated day!

Carcinoid—more likely to have an effect on the right heart valves that is mediated by substances secreted by primary carcinoid tissue located in the liver. Direct metastatic spread is less likely.

Carcinoid—more likely to have an effect on the right heart valves that is mediated by substances secreted by primary carcinoid tissue located in the liver. Direct metastatic spread is less likely.

Imaging Modalities Utilized to Characterize Cardiac Masses

2-D—it is critically important to evaluate cardiac masses utilizing a multitude of views in order to appreciate the true functional anatomic features of the mass.

2-D—it is critically important to evaluate cardiac masses utilizing a multitude of views in order to appreciate the true functional anatomic features of the mass.

3-D—real time 3-D imaging has been demonstrated to better elucidate the anatomical relationships of intracardiac masses, and may alter surgery when utilized intraoperatively.

3-D—real time 3-D imaging has been demonstrated to better elucidate the anatomical relationships of intracardiac masses, and may alter surgery when utilized intraoperatively.

Contrast echocardiography—contrast echocardiography may be utilized to define the vascularity of a mass and enable more precise categorization. For example, papillary-type atrial mxyomas, which are friable and associated with neurological events, demonstrate relative avascularity when compared to the solid ovoid type.

Contrast echocardiography—contrast echocardiography may be utilized to define the vascularity of a mass and enable more precise categorization. For example, papillary-type atrial mxyomas, which are friable and associated with neurological events, demonstrate relative avascularity when compared to the solid ovoid type.

Questions

1. Which is the most common primary malignant cardiac tumor in children?

2. The most common primary tumor affecting valves is:

3. A filamentous embryological remnant located in the RA

4. Which of the following is/are true regarding angiosarcoma?

A It is the most common primary malignancy of the heart

B It displays a fondness for the right atria of middle-aged men

C They may be either intracavitary or infiltrative

5. Which of the following statements is/are true?

A Myxomas demonstrate relative avascularity

B Carcinoid primarily affects the left side of the heart

C Lung cancer is the most common type to metastasize to the heart

6. Which of the following is/are true?

A The Eustachian valve is associated with the coronary sinus

B Most vegetations occur on the right side of the heart

C The Thebesian valve is associated with the junction between the RA and IVC

7. Which is are true regarding papillary fibroelastoma?

A The most common primary tumor affecting valves

B It resembles a small (<1 cm) vegetation, but is usually seen on the downstream side of a valve

C Found more frequently in association with left heart valves in patients greater than 50 years of age

8. Which is/are true of fibromas?

A Second most common benign cardiac tumor in children (rhabdomyoma is first)

B Most frequently seen in the ventricle

C Although benign in tissue type, may be associated with impaired ventricular filling and/or arrythmias