Intra-abdominal Pelvic Anatomy

The anatomy pertinent to surgery of the uterus, adnexa, and neighboring pelvic structures is not only intraperitoneal but, perhaps more important, extraperitoneal.

Uterine Support

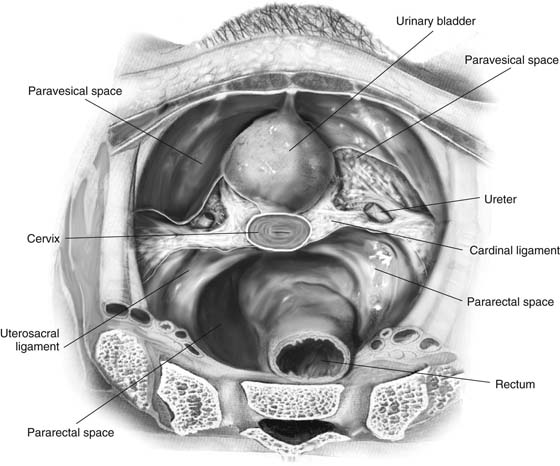

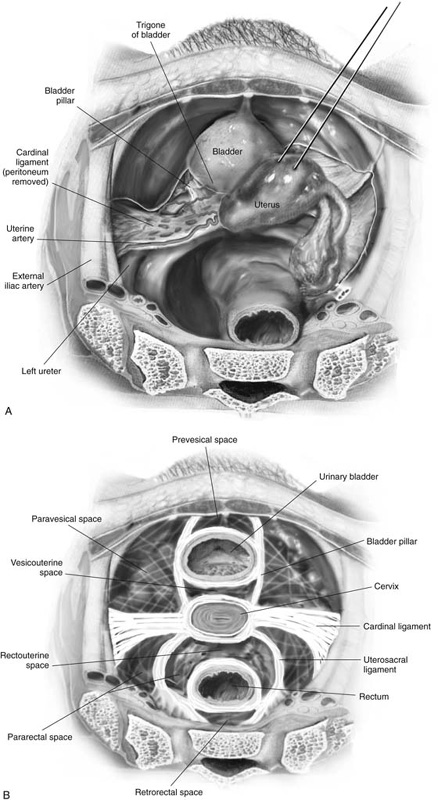

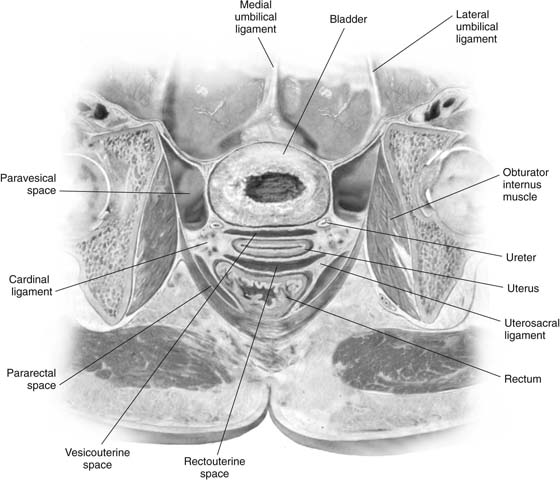

The main uterine support is provided by the cardinal ligaments, which extend from roughly the level of the cervicoisthmic junction peripherally in a fanlike fashion laterally and posteriorly, where it blends with the fat and fascia of the pelvic sidewall (Fig. 9–1). This ligamentous structure divides the pelvis into right and left paravesical spaces anteriorly and pararectal spaces posteriorly (Fig. 9–2A, B). The cardinal ligament can be divided into an upper portion at the junction of the uterus and cervix and a lower portion at the juncture of the cervix and vagina (Fig. 9–3).

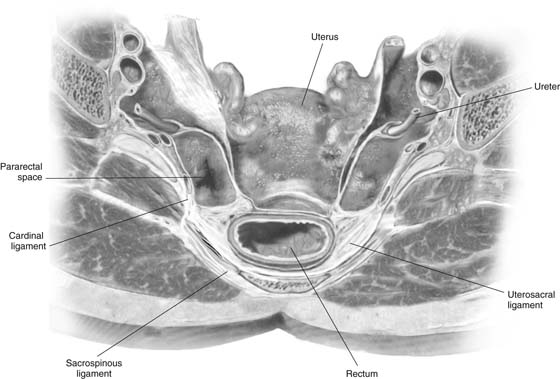

The uterosacral ligaments connect to the cardinal ligaments at the cervical attachment of the latter and extend posteriorly and inferiorly toward the ischial spines and sacrum. However, these terminal attachments may be difficult to identify precisely (see Figs. 9–2 through 9–4). Between the uterosacral ligaments and covered by a peritoneal reflection onto the posterior aspect of the uterus is the top of the rectovaginal septum. This is the portal of entry to the rectouterine space.

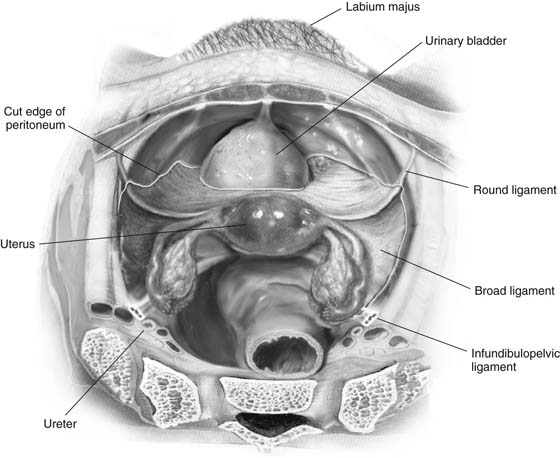

The round ligaments arise from the anterolateral fundus and extend ventrally and laterally to the anterior abdominal wall, entering the inguinal canal and terminating in the fat of the labium majus on either side (Fig. 9–5). The round ligaments, in contrast to the other “ligaments,” are mainly composed of smooth muscle. The infundibulopelvic ligaments are in reality peritoneal vascular conduits, which carry the ovarian vessels from the posterolateral pelvic brim in an anteromedial direction to gain attachment to the uterus at the level of the cornua.

The broad ligament is a tentlike structure that comprises anterior and posterior peritoneum containing areolar fat (see Fig. 9–5). The “ligament” begins anteriorly at the round ligament and finishes posteriorly at the infundibulopelvic ligament.

FIGURE 9–1 The uterine fundus has been excised. The cardinal ligaments stretch from the cervix to the sidewall and are contiguous with the uterosacral ligaments and the paravesical, pararectal, and paravaginal fascia. Note the course of the ureters as they penetrate the cardinal ligaments.

FIGURE 9–2 A. The cardinal ligament may be divided into an upper portion at the junction of the uterine body and cervix and a lower portion at the junction of the cervix and vagina. B. The various anatomic spaces within the pelvis are schematically demonstrated.

FIGURE 9–3 The sagittal view demonstrates the relationships between the cardinal ligaments and the various anatomic spaces. Note that the sidewall largely consists of the obturator internus muscle mass and its fascia.

FIGURE 9–4 Sagittal view of the posterior pelvis shows the uterosacral ligaments, sacrospinous ligaments, and cardinal ligaments and their relationships to the viscera. Note the position of the ureter from this perspective.

FIGURE 9–5 The peritoneum has been opened, exposing the broad ligaments. This is the easiest portal of entry into the retroperitoneal space and the pelvic sidewall structures. The weblike fat contents are easily and bloodlessly dissected.

Pelvic Anatomy

Exposure of extraperitoneal structures must be accomplished safely and expeditiously. Access to the left ureter, left iliac vessels, and left ovarian vessels can be gained by sharply incising the peritoneal sidewall attachment of the sigmoid colon; more extensive exposure is offered by continuing the separation of the descending colon from the psoas major muscle (Fig. 9–6A, B). Similarly, opening the top of the broad ligament between the round and infundibulopelvic ligaments lateral to the pulsation of the external iliac artery (i.e., over the psoas major muscle) provides easy access to both right and left sidewall/retroperitoneal spaces (Fig. 9–7A–C). After entry to the retroperitoneum is gained, exposure of the pelvic ureter and uterine vascular supply requires incision of the broad ligament (Fig. 9–8A–D).

The course of the ureter from the point where it enters the pelvis to the point where it enters the bladder consists of anatomic landmarks that every obstetrician-gynecologist must know. The greatest number of surgery-related injuries to the ureter happens to the segment between the uterine artery crossing point and bladder entry. The uterine artery crosses the lower third of the pelvic ureter obliquely lateral and cephalad to the uterus. The ureter may be crossed again by the inferior vesical artery as it enters the bladder. The vaginal artery lies behind the ureter. The distal ureter is exceedingly close to anterolateral fornix of the vagina (Fig. 9–9A–I).

The ureters gain entry to the pelvis by crossing lateromedially over the psoas muscle; they cross the common iliac vessels at the point where the external and internal iliac arteries bifurcate (Fig. 9–10). The ureter descends into the pelvis medial to the internal iliac artery (hypogastric artery) and obturator fossa (Fig. 9–11). Its course is consistently one of deep descent and medial swing, particularly after the uterine artery crosses over it (superior and anterior). The entire course of the right ureter can be seen in Figure 9–12.

The left ureteral course is complicated by the position of the sigmoid colon overlying it and the presence of the inferior mesenteric vessels that supply the left colon (see Fig. 9–7A, B). The left ureter crosses the common iliac artery in concert with the ovarian arteries and descends into the pelvis, following a similar course to the right ureter. The ovarian vessels cross the common iliac in concert with the ureter. The ureter is behind the ovarian vascular pedicle and slightly medial to it (Figs. 9–13A–D and 9–14A).

The arterial blood supply to pelvic structures emanates from the abdominal aorta, which branches into right and left common iliac vessels at the L4–L5 vertebral level (Figs. 9–14B and 9–15 through 9–18A). To the right of the aortic bifurcation lies the origin of the inferior vena cava. The cava is formed by the union of left and right common iliac veins (Fig. 9–18B). The left common iliac veins cross in front of (anterior to) the sacrum within the bifurcation of the aorta and under the right common iliac artery to join the right common iliac vein, which lies posterior to the right common iliac artery (Figs. 9–18C, D). The inferior mesenteric artery arises from the lower left side of the abdominal aorta, giving off numerous branches to the left colon and sigmoid.

Following bifurcation, the external iliac artery assumes a relatively superficial position just medial to the psoas major muscle (Fig. 9–19). The external iliac vein is considerably larger than the artery and lies beneath (posterior to) it. The vein covers the entrance to the obturator fossa, which can be exposed by carefully retracting the vein upward (Fig. 9–20). The fossa is demarcated by the obturator nerve and artery, which cross through this fat-laden space whose lateral boundary is the obturator internus muscle (see Figs. 9–20A–C and 9–21). The obturator neurovascular bundle leaves the pelvis and enters the thigh medially via the obturator foramen (Fig. 9–22A, B).

The major portion of the pelvic blood supply is derived from the hypogastric vessels (internal iliac arteries and veins), which branch within the obturator fossa (Fig. 9–23). Curiously, the major risk in dissecting the fossa is related to the numerous and anomalous veins that occupy the lateral floor of the fossa (Fig. 9–24). The hypogastric artery branches into anterior and posterior divisions. The posterior division plunges down into the deep recesses of the pelvis toward the ischial spine, in turn branching into a large superior gluteal artery and a smaller lateral sacral artery (Fig. 9–25). These are important sources for collateral pelvic circulation. The anterior division gives branches to the bladder, uterus, vagina, obturator, and internus and pectineus muscles, and terminates in the inferior gluteal and internal pudendal arteries.

During simple or radical hysterectomy, an understanding of the relationships of the structures mentioned earlier is vital to avoiding unnecessary blood loss and injury (Figs. 9–26 and 9–27).

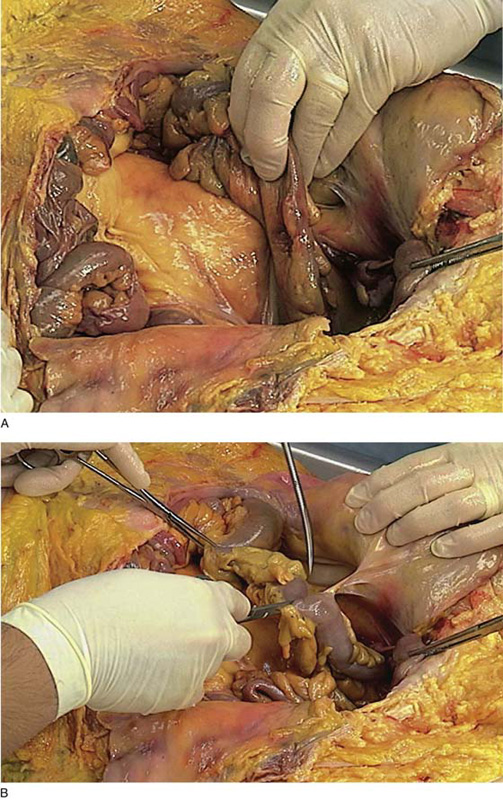

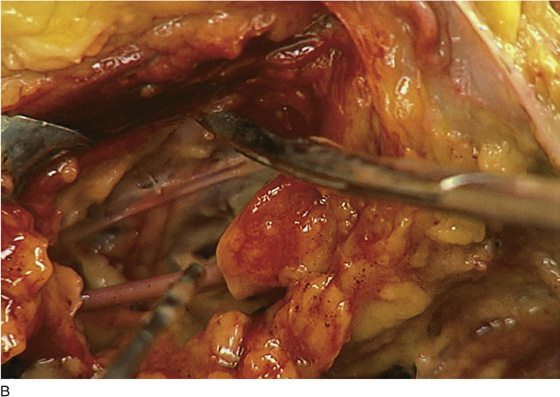

FIGURE 9–6 A. The uterus is pulled up and forward with a long Kocher clamp. The left tube and ovary are seen to lie deep in the pelvis. The sigmoid colon has been elevated and pulled medially to expose the left adnexa. B. The attachments of the sigmoid colon to the parietal peritoneum of the left abdominal wall and gutter are clearly in view as traction is placed on the sigmoid colon in the direction of the midline. Typically, the sigmoid colon overlies the left adnexa, which is attached to the parietal peritoneum via the ovarian vascular pedicle (infundibulopelvic ligament).

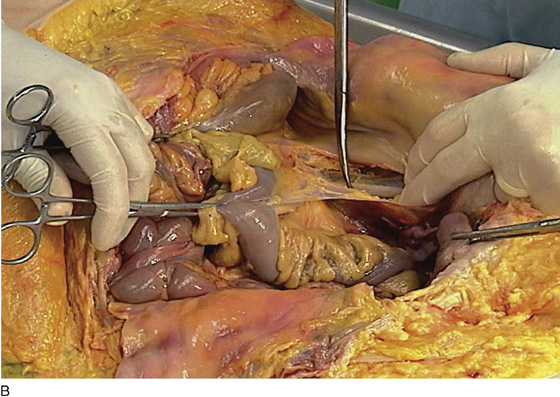

FIGURE 9–7 A. The peritoneal attachments of the sigmoid and descending colon have been cut. The retroperitoneal space has been entered on the left side. B. Further dissection permits mobilization of the sigmoid colon, and excellent exposure of the psoas major muscle intersects with the sigmoid colon to create an almost perfect 90° angle. C. The psoas major muscle and the psoas minor tendon as well as the genitofemoral nerve are exposed as a result of incising and dissecting the sigmoid colon peritoneal attachments.

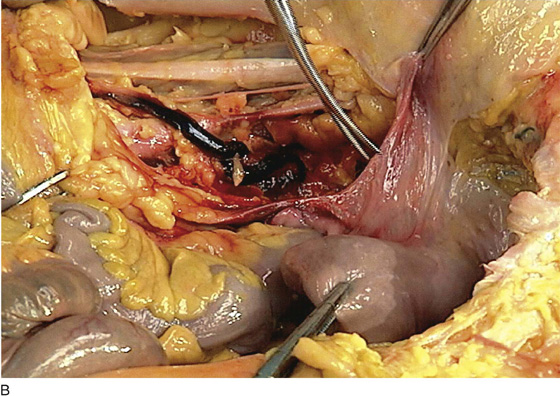

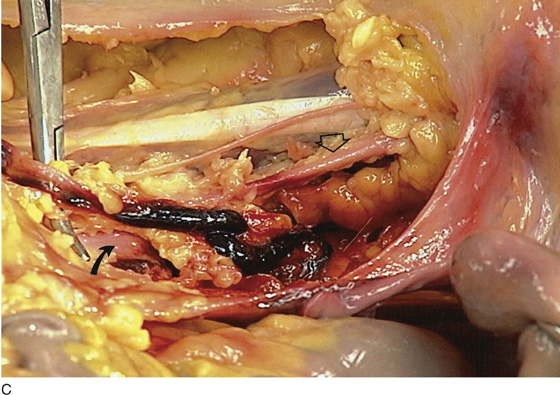

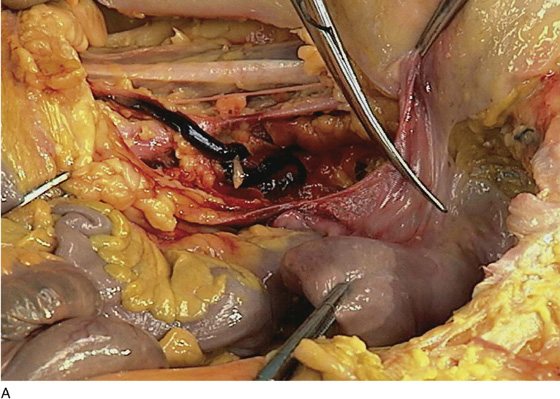

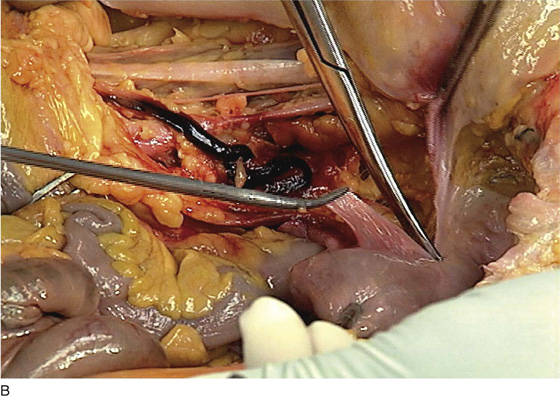

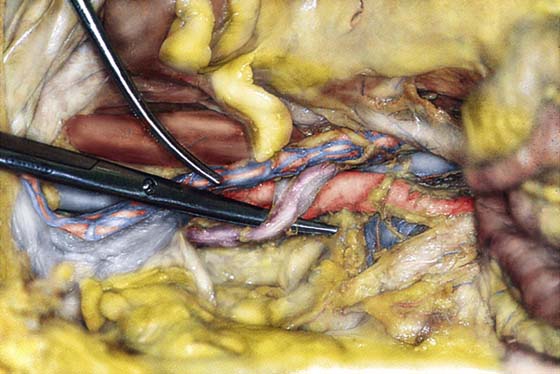

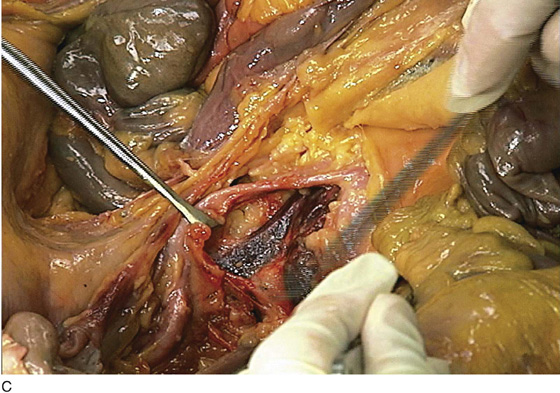

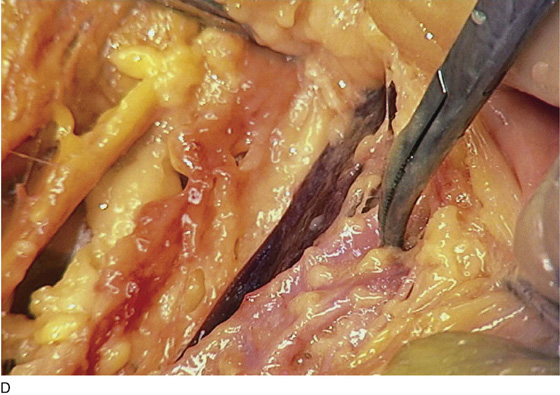

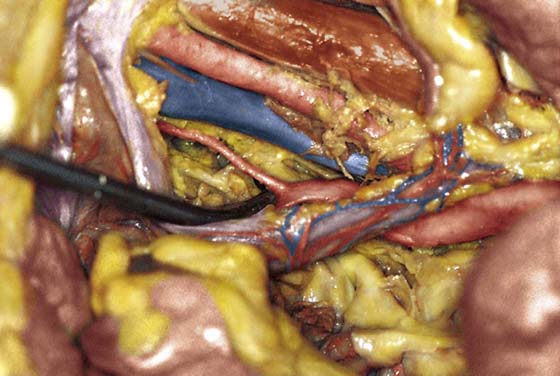

FIGURE 9–8 A. The uterus has been placed on traction by elevating the fundal clamp and pulling cranially. The tonsil clamp to the left exposes the left broad ligament. B. The left ureter (hemorrhagic) crosses the common iliac artery and descends into the pelvis medial to the internal iliac (hypogastric) artery. The uterus is pulled to the right and the left broad ligament is likewise placed on traction for subsequent incision. C. Close-up view of the left ureter (above the clamp and hemorrhagic) crossing the left common iliac artery (arrow). Note the left external iliac artery just medial to the psoas major muscle (open arrow). D. Immediately above the forceps, the dark blue common iliac vein is visible. It lies below the common iliac artery.

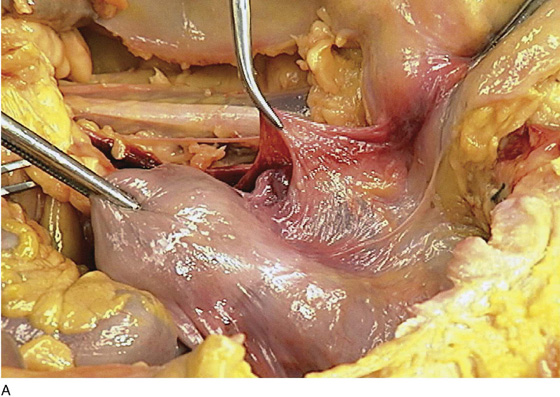

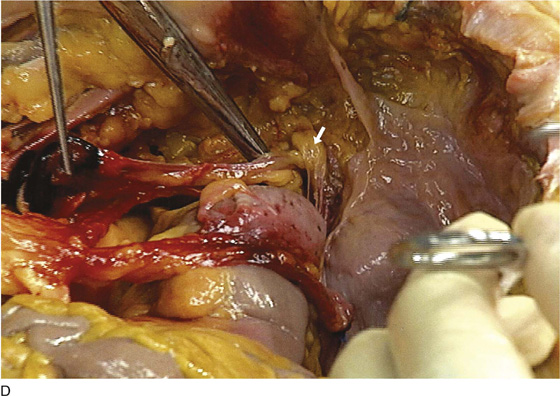

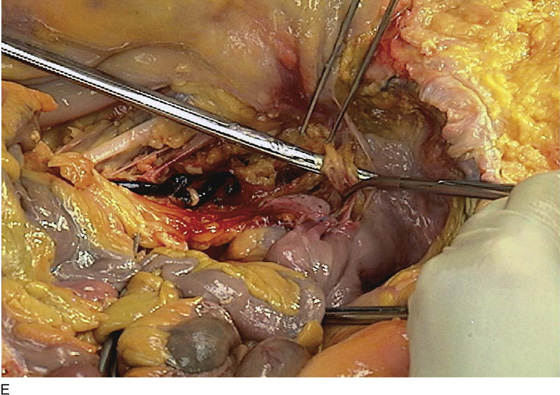

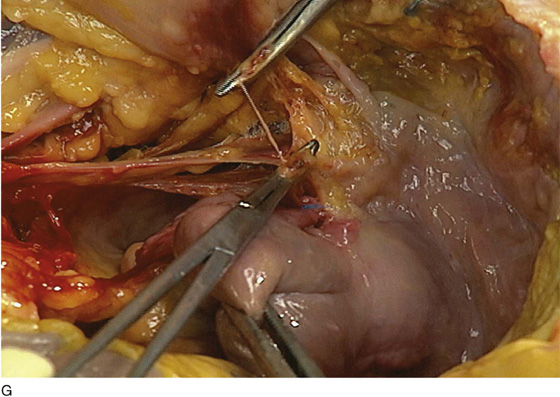

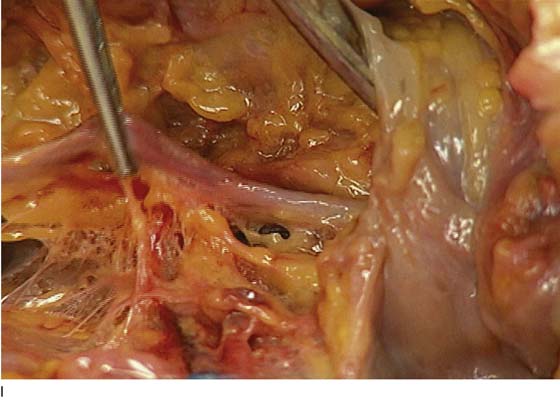

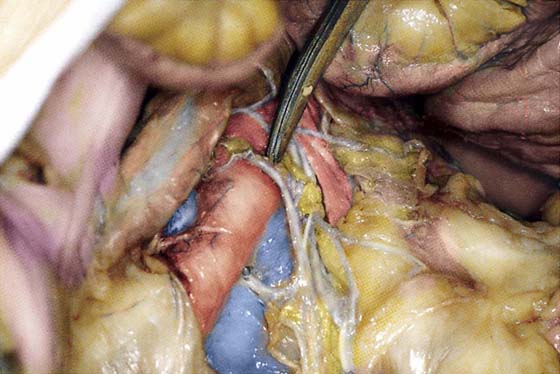

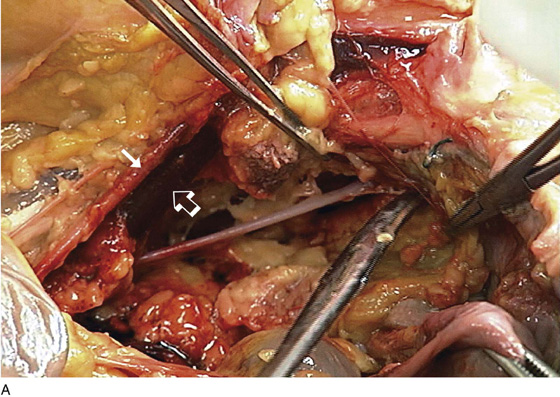

FIGURE 9–9 A. The broad ligament is cut with Metzenbaum scissors. B. The incision is carried downward to the cervicocorporal junction of the uterus. C. The uterine vessels are exposed and isolated with the use of Metzenbaum scissors. The ureter is crossing beneath the uterine vessels (arrow). The uterus is twisted to the right and is held in a Kocher clamp (lower right corner of the photograph). D. The broad ligament is completely opened. The view is from directly above looking down. The scissors are beneath the left ureter. The ureter is crossing under the uterine vessels (arrow). E. The uterine vessels are isolated. The Metzenbaum scissors have dissected a space between the uterine vessels and the ureter. The tonsil clamp has been placed across the vessels at the side of the uterus. F. Detail of the dissection shown in Figure 9–9E. The ureter is directly under the blades of the scissors. G. The uterine vessels have been clamped with tonsil clamps and cut to expose the underlying ureter. H. The ureteral dissection is continued to the point where it enters the urinary bladder (B). The uterus is labeled U. I. Magnified view of the ureter entering the bladder. The forceps is grasping the ureter at the point where the uterine vessels had previously crossed above.

FIGURE 9–10 The scissors separate the right ureter from the ovarian vessels (grasped by the clamp). Both structures cross the common iliac vessels to enter the pelvis. Note that the tip of the scissors points to the left common iliac vein as it crosses the sacrum. It will unite with the right common iliac vein to form the inferior vena cava, which is seen to the right of the bifurcation of the aorta.

FIGURE 9–11 A right-angle clamp retracts the ureter to expose the bifurcation of the right common iliac artery into external (above) and internal (below) iliac arteries. Note the blue vena cava to the right of the common iliac artery (upper right corner of photograph).

FIGURE 9–12 The entire course of the right ureter is seen from the point where it crosses the common iliac artery to its entry into the urinary bladder. The lateral clamp points to the vaginal artery. The medial clamp is directly in front of the uterine artery, where it crosses over the ureter. The sigmoid colon is covering the small uterus.

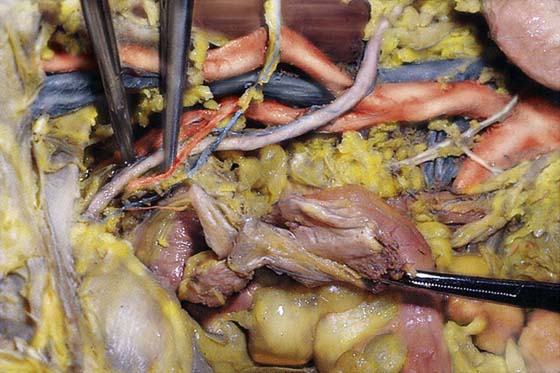

FIGURE 9–13 A. The uterus is held on traction with a clamp. The forceps elevate the extension of the ovarian vascular pedicle to the retrocecal area. The tonsil clamp rests on the cecum. B. The enlarged view details the method by which the surgeon can extend the location of the ovarian pedicle into the retroperitoneum. Because the ureter is closely applied to the ovarian vessels (i.e., posterior and slightly medial), the surgeon can anticipate how a safe dissection to locate the ureter should proceed. C. The cecum is mobilized by cutting its peritoneal attachments and extending the incision cranially via the right gutter. The ureter and ovarian vessels cling together at the pelvic brim. D. The incision is carried carefully to the medial aspect of the ureter.

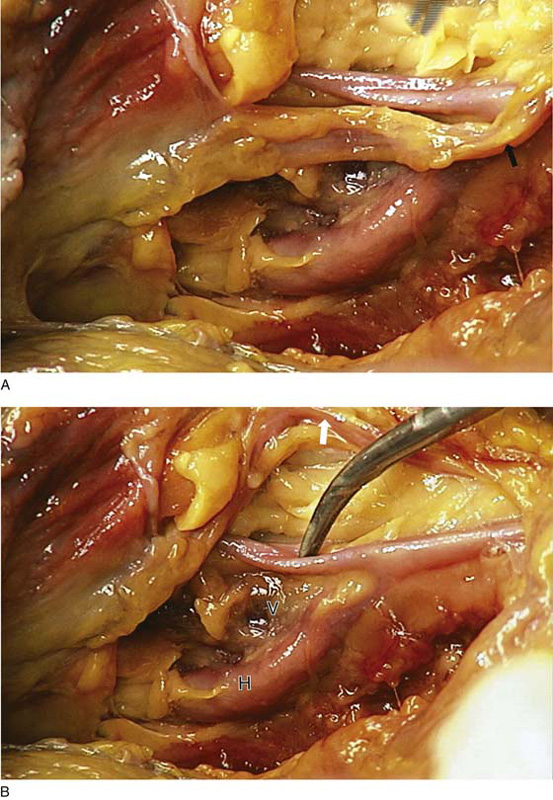

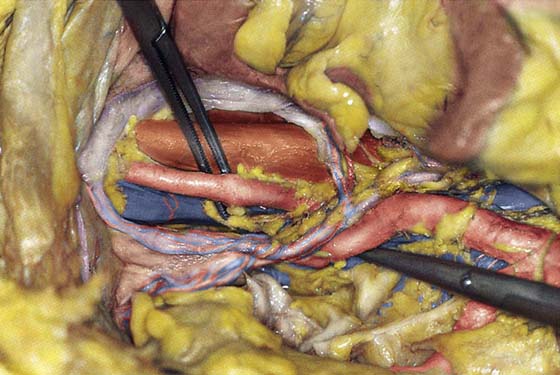

FIGURE 9–14 A. The ureter is traced caudally to the point where it crosses the common iliac artery. This picture shows the ureter (arrow) and the common iliac bifurcation. B. The ureter (white arrow at top of photo) has been retracted above the common iliac bifurcation. The tip of the tonsil clamp rests on the external iliac artery. The hypogastric artery (H) is quite large. At the “crotch” between the iliac arteries lies the external iliac vein (V), which is joined by the internal (hypogastric) iliac vein (located deep to the hypogastric artery) to form the common iliac vein.

FIGURE 9–15 The clamp rests on the aorta at its bifurcation. The hypogastric nerves are draped over the vessels.

FIGURE 9–16 The scissors rest on the inferior vena cava. The large left common iliac vein crosses the sacrum to join the right common iliac vein (barely seen lateral to the artery) to form the inferior vena cava.

FIGURE 9–17 A view from the foot of the table. The clamp is under the left common iliac vein. Note the middle sacral vessels partially obscured by the hypogastric plexus. The vena cava is seen to the right of the aorta and the right common iliac artery. The sacrum is just beneath the clamp.

FIGURE 9–18 A. The clamp rests on the bifurcation of the aorta. The right common iliac artery is lifted up by the tonsil clamp. B. The inferior vena cava lies to the right of the aortic bifurcation. The arrow points to the left common iliac vein. Note whether the presacral space has been exposed by incising the peritoneum and retracting the sigmoid colon to the left. The clamp points to the inferior vena cava. C. The Allis clamp grasps the edge of the posterior parietal peritoneum as the presacral space is entered. The left common iliac vein is the first structure that must be identified. The left iliac vein joins the right to form the vena cava, as is shown here. D. The clamp points to the aorta immediately cranial to the bifurcation. The inferior vena cava is to the right of the aorta.

FIGURE 9–19 The clamp dissects the right external iliac artery and lies between the artery and the blue right external iliac vein. The tip of the scissors lies beneath the right common hypogastric artery. The ureter, together with the infundibulopelvic ligament, crosses the vessels.

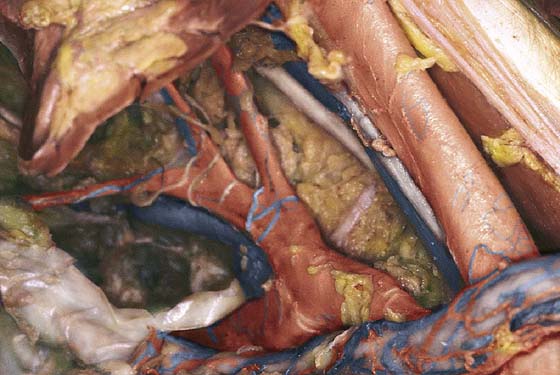

FIGURE 9–20 A. The obturator fossa has been cleared of fat. The external iliac artery (white arrow) and vein (open arrow) are seen in the background. The obturator nerve stretches across the fossa. B. The external iliac vein is held by a vein retractor. The scissors tip is directly under the vein. The obturator nerve and artery cross the space (fossa). C. Magnified view of vein held in the retractor (upper left) and scissors dissecting the obturator nerve.

FIGURE 9–21 The right obturator fossa has been exposed. Under most circumstances, the external iliac vein would require upward traction via a vein retractor. The clamp rests under the obturator artery, which is a branch of the anterior division of the hypogastric artery.

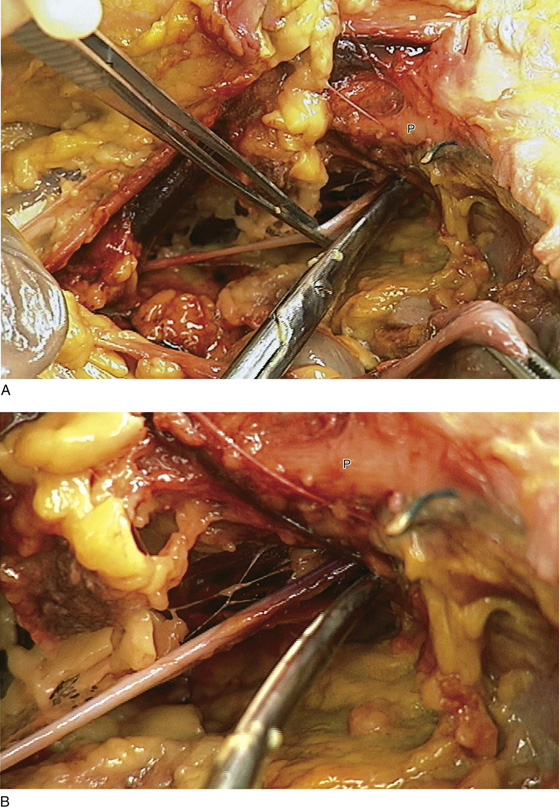

FIGURE 9–22 A. The nerve and vessels leave the obturator fossa via the obturator foramen (tip of scissors). The pubic bone (P) can be seen above the foramen. B. Magnified view of the nerve exiting the pelvis via the obturator foramen. The pubic bone (P) is seen in the background.

FIGURE 9–23 The scissors point to the obturator internus muscle. This forms the lateral boundary of the obturator fossa and the “pelvic sidewall.” The hypogastric artery (anterior division) is retracted medially with the hook.

FIGURE 9–24 The posterior division of the hypogastric artery is viewed clearly. The internal iliac vein is just below and slightly lateral to the artery.

FIGURE 9–25 View of the obturator fossa obtained during a pelvic lymphadenectomy. The uterus is pulled anteriorly and to the right for exposure.

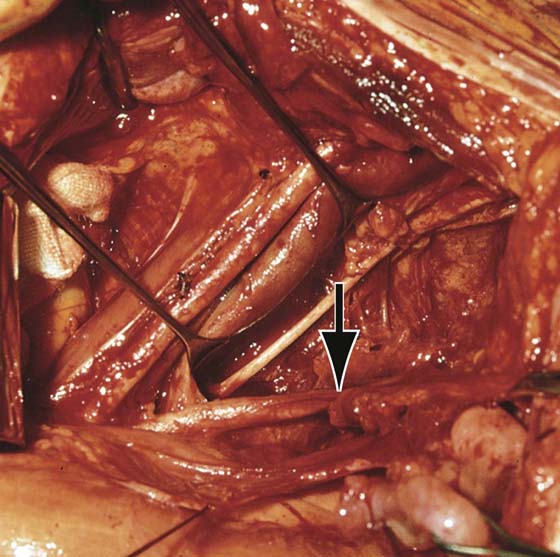

FIGURE 9–26 A vein retractor is positioned beneath the large external iliac vein, exposing the obturator fossa. The fat-containing lymph nodes have been cleared from the fossa. The obturator nerve has been exposed. The arrow points to the hypogastric artery. The ureter is medial to the hypogastric artery (traction ligature).

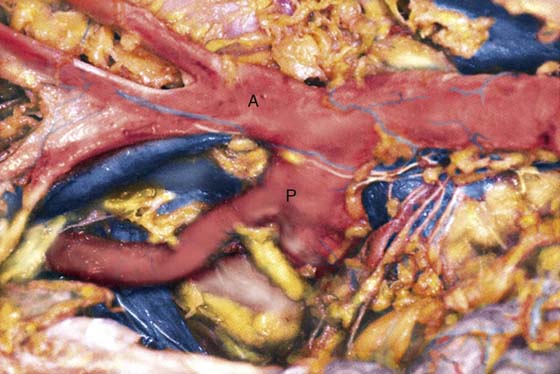

FIGURE 9–27 The entirety of the right hypogastric vessels is exposed. The two main divisions of the hypogastric artery (anterior and posterior), as well as their branches, are seen. A, anterior division; P, posterior division.