Intimate Partner Violence

Perspective

Epidemiology

Definition and Types of Intimate Partner Violence

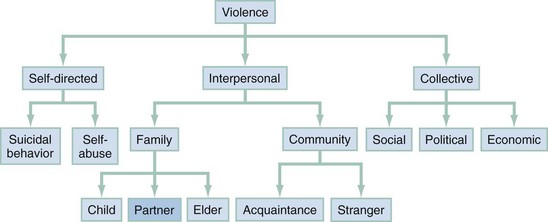

In 2002 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that “violence is a leading, world-wide public health problem” and then added that violence is not an intrinsic part of the human condition and is preventable. Gro Harlem Brutland, the Director General of WHO, wrote, “to many people, staying out of harm’s way is a matter of locking doors and windows and avoiding dangerous places. To others, escape is not possible. The threat of violence is behind those doors—well hidden from public view.”1 The WHO report distinguishes three general categories of violence—individual, interpersonal, and collective—and then further divides interpersonal violence into familial or stranger violence. IPV is a form of interpersonal, familial violence (Fig. 68-1).

IPV has been defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as the threat or infliction of physical or sexual violence by a current or former adolescent or adult intimate partner or spouse. This violence is often accompanied by psychological abuse.2 The physical, sexual, and psychological forms of IPV occur as a pattern of assaultive and coercive behaviors. Physical violence includes aggressive behaviors, such as pushing, hitting, slapping, punching, kicking, biting, burning, strangulation, using objects and weapons, and controlling access to physical needs, such as health care, medications, food, or shelter. Sexual abuse includes behaviors such as forced sex, coerced sex with a partner or other persons, and violence in association with sexual assault and rape, as well as prevention of or interference with the use of birth control and refusal to use condoms to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Psychological abuse includes words and behaviors meant to intimidate, degrade, humiliate, or isolate the victim from family and friends. Psychological abuse may also manifest as behaviors to arouse fear in the victim, such as violence or threats of violence against family members, stalking, attacks against pets, and destruction of property; controlling access to food, shelter, clothing, transportation, and money; and controlling employment and social or professional activities.

In the past, IPV has been referred to by a number of different terms. These include domestic violence, spouse abuse, wife abuse, battering, battered woman, and wife beating. However, the use of the term intimate partner violence is recommended, as it is a more inclusive term and applies equally to adolescents and adults, females and males, opposite- and same-sex intimate partners, married and unmarried individuals, and current and former intimate partners.2 State penal codes may use slightly different definitions of IPV from those of the CDC, especially as it pertains to the nature of the relationship between the two individuals or the forms of abuse that have transpired. The term domestic violence is generally used by the criminal justice system when referring to partner violence, whereas intimate partner violence is the preferred term of the CDC; of note, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) includes IPV as a form of adult maltreatment.

Prevalence

There are numerous population-based and health care–based studies that report prevalence rates of IPV victimization. Because of the different types of IPV (i.e., physical, sexual, psychological and emotional), the pattern of the violence (i.e., first episode, ongoing, intermittent, previous experience), and the population being surveyed, the reported IPV victimization prevalence rates vary widely. The prevalence of IPV victimization is often expressed as either a 1-year prevalence (the proportion of the population experiencing IPV in the previous year) or as a lifetime prevalence (the proportion of the population that have ever experienced IPV). To fully understand the meaning of reported IPV prevalence rates or to be able to compare IPV prevalence rates between studies, one should look at the population being studied, the types of abuse being measured, and the period of time being studied. The variation in research methodology among studies makes IPV surveillance challenging. In an attempt to improve IPV surveillance, the CDC published recommended uniform definitions and data elements for IPV research.2

The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) and the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) are two large population-based surveys. In the NCVS in 2010, a randomized telephone survey of 41,000 households and approximately 73,300 males and females 12 years and older, 22% of violent crime against women was IPV compared with 5% against men,3 and about 80% of IPV victims were women.4 In the NISVS in 2010, a random telephone survey of 7421 men and 9086 women 18 years and older, 35.6% of women and 28.5% of men reported having been physically or sexually assaulted and/or stalked by an intimate partner during their lifetime; 5.9% of women and 5.0% of men reported having been physically or sexually assaulted and/or stalked by an intimate partner within the previous year.5 According to one survey, women in same-sex relationships reported lower rates of IPV (11%) than women in opposite-sex relationships (20%). On the other hand, men in same-sex relationships reported increased rates of IPV (23%) compared with men with female partners (8%).6 According to Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data from 2005, 23.6% of women reported a lifetime history of IPV and 11.5% of men reported IPV.7 The rates are about the same in rural and urban populations.8 Domestic violence also occurs in older women.9 The National Women’s Health Initiative reported that 11% of women aged 50 to 79 years disclosed that they had experienced physical or psychological abuse over the previous year.10

The prevalence rates of IPV among emergency department (ED) patients are greater than those in population-based studies. Although numerous IPV prevalence studies have been conducted in the ED, they are difficult to compare owing to differing methodologies. The majority of ED-based studies have examined IPV prevalence rates among women. In general, ED-based studies report the incidence of acute abuse, 1-year, and lifetime prevalence rates. Based on several ED-based surveys, 1 to 7% of all adolescent and adult females who came to the ED for any reason did so as a result of an acute episode of physical abuse.11 Moreover, 14 to 22% of all female patients in the ED disclosed that they had experienced IPV in the previous year.12,13 From the Michigan Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance System, all female assault victims were identified based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnostic and E codes. Of 3111 assault victims, 2926 were victims of physical or sexual violence, and 38.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37.1-40.6) of these cases were attributed to IPV.14 The lifetime prevalence of IPV among female ED patients may be as high as 54%.15 Few studies have investigated the prevalence rate of IPV among male ED patients, and those that did failed to differentiate whether the relationship was homosexual or heterosexual IPV, did not specify whether injuries were sustained in the course of partner retaliation, defense, or retribution, and did not differentiate the force used and nature of injuries sustained.16 The chief concern in comparing male and female victimization is that the dynamics and consequences of the abuse may be very different.

Homicide is one of the top five leading causes of death for females aged 1 to 34 years.17 According to the National Violent Death Reporting System report on 2007 data, 64.4% of intimate partner–related homicides involved female victims, whereas 13.7% of non–intimate partner–related homicides involved female victims. The highest percentage of victims and suspects (26.1 and 23.5%, respectively) were persons aged 35 to 44 years, 37.8% of whom were married at the time of death.18 Women are killed by current or former intimate partners almost nine times more often than by strangers.19 IPV fatalities do not usually occur as a freak event in an otherwise happy family. IPV is a precursor to the homicide in 65 to 75% of cases.20 Of even greater concern for health professionals is that almost half of IPV homicide victims saw a health care provider (HCP) within the year before their death.21,22 The incidence of homicide attributed to IPV has continuously decreased since the mid-1970s, a phenomenon that is attributed to societal shifts to more openly address family violence and to improvements in criminal justice, social service, and health system responses to both victims and perpetrators.

The annual economic cost to society in the United States is estimated at more than $8 billion dollars for direct medical and mental health services as well as lost productivity.23 Studies have found that female patients with documented IPV have higher health care system utilization and costs than those without IPV.24,25 Furthermore, higher health care system utilization and costs were seen in children whose mothers had experienced IPV, even if the abuse had ceased before the children’s birth.26

Risks for Victimization

A few individual factors have been identified that appear to place persons at risk for IPV victimization: female gender, younger age,27 exposure to violence in family of origin,28,29 presence of a physical or mental disability,30 and use of alcohol. Abbott found that among women patients who abused alcohol, 71% also experienced IPV.15 Alcohol use plays a role in both victimization and perpetration of violence, probably because of its disinhibitory effects. In Caetano’s study, 30 to 40% of men and 27 to 34% of women arrested for IPV perpetration were drinking at the time of the event.31 If men were drinking at the time of the physical assault, their female partners were at 3.6 (95% CI 2.2-5.9) times greater risk of sustaining a serious physical injury.32

Other factors appear to contribute to the risk for IPV because either they contribute to relationship stress or they heighten victim vulnerabilities. IPV appears to occur at increased rates in relationships with lower socioeconomic status in which the abuser is unemployed or at a lower level of academic achievement.32–34 Homeless women, in general, have higher cumulative rates of violence over the life span than women with stable housing,35 and fleeing IPV homes has been noted to be one of the causes of homelessness in women. Immigrant women are another vulnerable population, as they may be reluctant to disclose IPV, fearing deportation of themselves and/or their spouse. Immigrant women may be further isolated from services owing to language barriers, lack of social support, or lack of economic independence.36 In one study of 1861 New York femicides, the strongest predictors of intimate partner femicide victimization were foreign country of birth and young age.37

Two presentations should provoke consideration of IPV as an underlying or comorbid condition. One presentation is the woman with injuries to the head, face, or neck.38 Muelleman and other researchers found maxillofacial injuries to be the most common injury type among battered women.39,40 Another presentation that prompts consideration of IPV is the female patient who has attempted suicide. Abbott found that among female patients with a lifetime history of a suicide attempt, 81% also had a history of IPV.15 More than 90% of women hospitalized after a suicide attempt report current severe IPV.41,42 Women seen at one ED in England as a consequence of IPV assault (N = 294) were compared with a matched control (N = 558) to determine risk of future self-harm. IPV victims had a relative risk of 3.6 (95% CI, 2.1-6.5) of returning to the ED because of future episodes of self-harm.43

Risks for Perpetration

Most of the research on persons who abuse their intimate partner is done on men who have committed violence of sufficient severity to have been arrested. Although batterers are a heterogeneous group, there are three typologies commonly described: (1) the borderline or dysphoric individual, (2) the antisocial or generally violent individual, and (3) the “family only, no psychopathology” batterer.44 The men in the borderline or dysphoric group are often described as both charming and moody with “Dr. Jekyll–Mr. Hyde” personality changes from one extreme (complacent) to another (rageful). High rates of alcohol and drug use appear in this group, as well as increased contacts with police for violent or disorderly conduct offenses, and increased concerns about rejection or abandonment. The antisocial or generally violent batterer is described as “self-centered, self-absorbed, and lacking in empathy.”44 Intimate partners are viewed as objects or possessions that serve the perpetrator’s needs. Although he may appear confident and exciting, he also manipulates and imposes his values on others. Antisocial batterers usually commit both physical and sexual violence that is more severe than with the other two types, as well as committing more violence outside the family. The third typology is composed of men described as the “guy next door,” not violent outside the home but usually with evidence of passive dependency or obsessive-compulsive personality style. They are rigid, rule bound, and conventional. Any deviation from “the rules” can cause internalized resentments that occasionally erupt in aggressive outbursts of hostility and violence.44 Other factors associated with IPV perpetration include younger age, lower socioeconomic status, exposure to violence in the family of origin,45 alcohol abuse, history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) (anger flares and poorer impulse control), and highly or abnormally spouse-specific dependency.46,47

Risks to Children Living in Intimate Partner Violence Homes

Children who live in IPV homes often witness the violence and suffer physically and emotionally,48,49 and the health impact can be acute or can lead to long-term health risks. The risk of exposure begins in the prenatal period. Pregnant women who are abused are more likely to smoke, consume alcohol, and use illicit drugs than nonabused pregnant women.50,51 Pregnant women who experience IPV physical abuse experience miscarriage,52 premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor,53 and placental abruption at higher rates than pregnant women who have abdominal trauma from other causes.54–56

Long-term health risks associated with child exposure to adult IPV have been elucidated through the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study based on data collected from 17,337 adult health maintenance organization members. Each person was assessed for exposure to adverse childhood experiences (verbal, physical, or sexual child abuse as well as family dysfunction caused by an incarcerated, mentally ill, or substance-abusing family member; IPV; or absence of a parent because of death or divorce or separation). Adverse childhood experiences have been linked to a range of adverse outcomes in adulthood, including substance abuse, depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and premature mortality.57–59 Adverse childhood experience exposure has also been linked to risk of perpetration and victimization of adolescent dating partner violence.60,61 Trauma-related adverse childhood experiences have demonstrated a “dose-response” relationship to 18 selected health outcomes.57

Children in IPV homes are at increased risk for direct physical abuse by the IPV abuser and less often by the IPV victim.62–64 Some state child welfare data have demonstrated that IPV appears to be associated with the most severe and fatal cases of child abuse.65 Children of IPV mothers have been found to be twice as likely to be re-reported to Child Protective Services than children of non-IPV mothers.66

Of great interest is the neurobiologic impact of exposure to violence at a young age. Chronic stress can cause the emotional, more primitive parts of the developing infant or toddler brain to become overly active or reactive to the environment and may affect myelination and synaptogenesis, thus resulting in problems with learning, memory, and behavior.67 Infants exposed to severe IPV in the home environment have demonstrated severe post-traumatic symptoms, as have their mothers.68

Special Considerations for Adolescents in Abusive Relationships

In a nationally representative sample of 7500 adolescents, 12% reported an experience of physical violence in an opposite sex relationship in the previous 18 months. If the question included sexual, physical, or psychological abuse, the rate rose to 32%.69 Miller and colleagues found that 40% of adolescents who sought care at adolescent health clinics disclosed IPV—32% with disclosed physical abuse and 21% sexual abuse.70 In a 2009 survey conducted by the CDC, 9.8% of male and female high school students reported an episode of dating violence (being hit, slapped, or physically hurt) in the preceding year.71 Higher rates are found in rural populations and when youth from lower socioeconomic groups were surveyed.72,73 Surveys show that boys and girls both report acts of physical aggression; however, girls report experiencing more serious acts, such as strangulation or use of a weapon in the physical assault or rape.74,75 Girls are more likely to be worried or scared of relationship violence, and boys minimize the psychological impact of the aggression; however, this may be more of an enculturated response than a true reflection of boys’ level of anxiety.76 Complicating understanding regarding prevalence of relationship violence in teens is the fact that in some states it is reported as child abuse and in others as IPV. Pregnant teens seem to be a high-risk population for prior exposure to violence. In one study of 724 pregnant adolescents, 12% had been assaulted by the man who had impregnated them, and of those who had experienced relationship violence, 40% also reported having experienced violence by a family member or other relative.77,78

Adolescents are more likely to endorse stereotyped gender roles (dominant or aggressive males and submissive or supportive females) and are more likely to interpret jealousy, violence, or controlling behaviors as signs of love or devotion.79 Adolescents are also less likely to disclose abuse to parents, from whom they are trying to individuate and separate, and less likely to disclose abuse to peers for fear of being considered odd or rejected by the peer group.80 Homosexual teens have the additional anxiety of being “outed” should they disclose the abuse.81

Etiology

Intimate Partner Violence Social Ecology Model

There are multiple theoretic explanations for the cause of IPV; these can best be organized with the Social Ecology Model, which nests individual, family, community, and cultural factors.82

The “individual” layer includes the biologic, ontogenic, or experiential makeup of a person, such as childhood exposure to IPV as well as certain personality psychopathologies.44,82 A small number of studies have shown a relationship between mild traumatic brain injuries and increased anger and aggression, poor impulse control, and decreasing marital satisfaction.44

The second nested layer is the “family” or the relationship itself, with its own style of communication, decision-making, and conflict resolution, also referred to as the “microsystem.” Male dominance and male control of financial decision-making in a family have been predictors of societies that have high rates of violence against women.82 Not surprisingly, couples with high levels of conflict also have a greater risk of physical violence, and this risk increases when there is an asymmetrical power structure within the relationship.82

The third nested layer is “community” or “exosystem” and refers to the neighborhood, institutions, local services, and social structures that surround the family. Although IPV occurs across all socioeconomic strata, it appears to be more common in families with low income and in unemployed men. It is likely that income level is not the critical variable, but rather the stress of poverty, crowding, or hopelessness that actually contributes to increased violence. Lack of social support for women and delinquent peer associations for men have both been associated with victimization and perpetration, respectively.82

Finally, the individual, family, and community all function within a society or culture with rules, laws, taboos, attitudes, and biases—also referred to as the “macrosystem.” The predominant cultural theory regarding the cause of IPV is Feminist Theory, which states that violence against women results from gender inequity, both ideologic (belief, norms, values) and structural (access to and positions within social institutions).83 The more unequal women are to men, the more likely men are to be violent to women.84,85

Forms of Intimate Partner Violence

Some IPV researchers have suggested that there may be two distinct forms of IPV: intimate terrorism and situational couple violence.86,87 The two forms are differentiated based on the use of power to control. Intimate terrorism is defined as “the attempt to dominate one’s partner and to exert general control over the relationship,” whereas situational couple violence is “violence that is not connected to a general pattern of control.”88 Situational couple violence is usually less injurious or severe, and more likely to be engaged in by either member of the couple. Intimate terrorism is characterized as more injurious, more frequent, and almost exclusively perpetrated by men against women.

In one study a five-item index to measure controlling behavior was created: (1) partner tries to limit your contact with family or friends,89 (2) partner insists on knowing who you are with and where you are at all times, (3) partner becomes jealous and does not want you to talk to other people, (4) partner prevents you from knowing about or having access to family income even if you ask, and (5) partner controls most or all of your daily activities (α = .72). The study found that controlling behaviors are present in 69% of physically violent relationships but present in only 11% of non–physically abusive controls.

Clinical Assessment

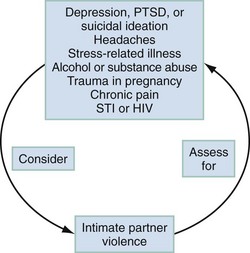

Patients who are currently experiencing or have previously experienced IPV may visit the ED for a wide range of health care issues. IPV patients may seek care after an acute physical or sexual assault or for the chronic sequelae related to a previous injury. They may seek treatment of an acute medical condition or care for a chronic illness exacerbated by IPV. In addition, IPV patients may require mental health care and may have conditions related to alcohol and substance abuse. IPV patients’ presentations may be obvious, such as a geometrically patterned physical injury, or subtle, such as headaches resulting from repetitive blunt head trauma. Therefore it is important that the HCP be aware of the broad possibility of IPV presentations as well as the comorbid conditions that are associated with IPV (Fig. 68-2).

When HCPs are eliciting a history from a patient with injuries, they should attempt to determine the mechanism of injury. If the patient attributes the injuries to interpersonal violence, the identity of the other person, as well as that person’s relationship to the patient, should be ascertained and documented. Not only is noting the nature of the relationship important for accuracy of diagnostic coding, but the intervention for a victim who lives with the assailant will be very different from the intervention for a victim of a stranger assault. If the injury is a result of IPV, the patient may be reluctant to divulge the information. Additional historical clues that an injury may be a result of IPV are a vague or changing history, a history that is inconsistent with the injuries, a statement by the patient that he or she is “accident prone,” and a past history of injuries.90

Many IPV patients seek care for chronic conditions that are a result of previous injuries or are comorbid medical conditions of the abuse. From results of a survey of 3568 English-speaking women that used BRFSS and Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) questions, the health status of abused and nonabused women were compared. Abused women were consistently and significantly at increased risk of psychosocial disorders (substance abuse, depression, anxiety, tobacco use), musculoskeletal disorders (degenerative joint disease, low back pain, joint trauma, cervical pain, acute sprains), reproductive complaints (menstrual disorders, vulvovaginitis, sexually transmitted infections), and others (confusion, headaches, urinary tract infections, abdominal pain, chest pain, respiratory infections, reflux disease, and lacerations).7,91 Other common medical presentations of IPV patients include cardiorespiratory illnesses (palpitations, chest pain, asthma exacerbations, shortness of breath), gastrointestinal disorders (functional bowel disease), and general constitutional complaints (weakness, fatigue, dizziness, chronic pain). Additional analyses of the 2005-2007 BRFSS data revealed that same-sex and opposite-sex IPV victims experienced similar poor health outcomes.92,93 When IPV victims experienced both physical and sexual IPV, they had even lower health outcome scores and more depression than those with physical abuse only.94

If the patient exhibits comorbid conditions common to IPV, the HCP should consider the possibility of IPV. Likewise, in the reverse, if the patient has experienced IPV, he or she should be questioned about the presence of any comorbid conditions that may warrant intervention (see Fig. 68-2). Other findings in the medical history that may be suggestive of IPV include a delay in seeking medical care or noncompliance with medications and/or medical appointments, which may be a result of the abuser controlling the patient’s access to care. Frequent visits to the ED and alcohol and substance abuse are also highly associated with IPV.

Physical Examination

IPV patients may come to the ED with acute injuries, or injuries may be an incidental finding discovered during the physical examination for medical complaints. When examining an injured patient, the HCP should look for clues that the injury may be intentional in nature, such as a central location (e.g., trunk, breasts), bilateral injuries (both arms or both legs), defensive injuries (e.g., ecchymoses on the back of the hand because of protecting the face), and patterned injuries (having the markings of an object such as the sole of a shoe or a burn with the imprint of an iron). Common locations for IPV injuries are the head, face, mouth, and neck. Types of injuries may include facial contusions, lacerations, fractures, traumatic alopecia, concussion, skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhages, and strangulation. Extremity injuries with “grab” marks (fingertip contusions) to the upper arms are suggestive of IPV. In one study, 2% of women with acute fractures related their injury to IPV, and one third of injured women revealed IPV exposure at some previous time.95

Mental Health Assessment

The HCP should assess any patient known or suspected to have been exposed to IPV for associated mental health conditions. IPV victims frequently experience depression, suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), insomnia, eating disorders, and alcohol and substance abuse. In a meta-analysis of mental health disorders among women who had experienced IPV, the weighted mean prevalence was 50% for depression, 61% for PTSD, and 20% for suicidality: higher prevalence rates were seen in women with more severe abuse or who were in shelters or court programs.96 These rates are all significantly higher than those in individuals who have not experienced IPV. IPV patients should also be questioned about alcohol and substance abuse, a common coping mechanism or form of pain control for IPV patients.

Other Intimate Partner Violence Injuries

Strangulation

Intentional strangulation occurs as a result of the perpetrator applying compression using a body part (one or two hands, forearm, or knee) or a ligature (a necklace or piece of clothing worn by the IPV victim). In asking patients if their partner attempted to strangle them, the lay term “choked” may be more appropriate to use because people often associate strangulation with a rope or object, whereas the word “choking” is associated with neck compression by the hands. Patients may complain of a hoarse voice, pain or difficulty swallowing, neck pain, difficulty breathing, loss of consciousness, incontinence, or confusion, or they may have no symptoms. On examination they may have a hoarse or muffled voice, difficulty swallowing, neck tenderness, respiratory difficulties, stridor, laryngeal fracture, facial petechiae, subconjunctival hemorrhages, ecchymoses or ligature marks on the neck, or altered mental status. They may also have normal examination findings that do not show any specific signs of strangulation.97,98

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

According to one study, 71% of women experiencing IPV have incurred TBI from a physical assault, and 51% incurred multiple episodes of TBI from repetitive assaults.99 Women appear to be at greater risk for postconcussive syndrome than men.100 IPV patients may also sustain TBI from “shaken adult syndrome,” resulting in diffuse axonal injury. Like shaken babies, these patients may have retinal hemorrhages, subdural hematomas, and ecchymoses of the upper arms and chest.101 IPV patients frequently report difficulty concentrating, memory problems, headaches, depression and anxiety, and confusion, as well as problems with judgment, problem-solving, and decision-making. In these cases, TBI can be missed, and patients may be labeled as having borderline personalities, post-traumatic stress, or depression. The sequelae of TBI, which is frequently undiagnosed and under-recognized, include neurocognitive deficits and long-term disability. It has been postulated that perhaps TBI interferes more with a patient’s ability to make safer choices than has been previously recognized. The IPV patient with mild TBI should be referred for a comprehensive neurocognitive assessment.102

Intimate Partner Sexual Abuse

Approximately 8 to 14% of women are sexually abused during their lifetimes by an intimate partner.34 Whereas societal biases result in intimate partner sexual abuse being considered less severe and the victim being disbelieved or blamed more often than in stranger sexual assault, the sequelae of intimate partner sexual abuse are at least as serious as those of stranger sexual assault. In addition, victims of intimate partner sexual abuse have been found to be more likely to sustain more serious nongenital injuries than victims of stranger assault.103 When questioning IPV patients about intimate partner sexual abuse and rape, the HCP should ask whether they have ever been forced by their partner to do sexual activities they did not want to do, rather than asking if they have been raped or sexually assaulted. Many IPV patients do not consider that they have been raped or sexually assaulted if their partner, husband, or boyfriend was the perpetrator. Many IPV patients also do not recognize that sexual activity under coercion or threat is a form of sexual assault. In one study, 19% of women reported pregnancy coercion (coercion to become pregnant) and 15% reported birth control sabotage (partner interference with birth control), both of which were associated with unintended pregnancy.104

Diagnostic Strategies

Milieu Considerations

Provide Privacy

One key behavior that promotes privacy is having a patient-only interview policy for at least part, if not all, of the interview, as patients who have experienced IPV may choose not to disclose their abusive relationship in the presence of their family, children, or friends, owing to shame and embarrassment. Research has shown that women experiencing IPV prefer to talk to their physicians alone about the abuse.105 If a partner is reluctant or refusing to leave, the HCP may need to be creative in finding an opportunity to talk to the patient alone, such as when a patient is in the radiology department. In addition, if an interpreter is needed, only trained and authorized hospital employees or a nationally based telephone interpreter service should be used. A hospital employee should not be used as an interpreter if the employee knows the patient. If a patient is asked to complete a written or computer-based questionnaire before being assessed by the HCP, he or she should be provided with a private, safe location in which to do this. Before questioning a patient about activities that must be reported to law enforcement, such as IPV-related injuries in some states, the HCP should inform the patient about the limits of confidentiality (see the later section on ethical considerations).

Provider Behaviors That Foster Disclosure

Numerous qualitative studies, primarily consisting of focus groups and surveys of women who are survivors of IPV, have been conducted to identify HCP behaviors that foster disclosure of IPV by patients. Women reported that they were more likely to disclose IPV to HCPs who listened attentively, conveyed compassion and concern, were nonjudgmental, and respected the woman’s right to autonomy in decision-making.106,107 In addition, IPV-related educational materials such as posters and patient brochures in the clinical setting made patients feel that the health care setting was a safe environment in which to discuss IPV with their HCP. Some women reported feeling more comfortable talking with a female HCP.108 However, a study by Gerlach in 2007 demonstrated that the gender of the HCP did not appear to be a barrier to disclosure.109

HCPs’ responses to surveys indicate that they are reluctant to ask patients about IPV for several reasons, including a lack of training about IPV, belief that there are no effective IPV interventions, time constraints, a perception that IPV patients are frustrating to deal with and do not follow HCPs’ advice, concerns about mandated reporting to law enforcement in some states, and a reluctance to go to court if required. In addition, HCPs’ personal experiences with IPV, their biases about victims and batterers, and their belief that IPV is not a health care problem are all barriers that may limit an HCP’s ability to diagnose IPV in the ED.110

Identification through Disclosure and/or Pattern Recognition

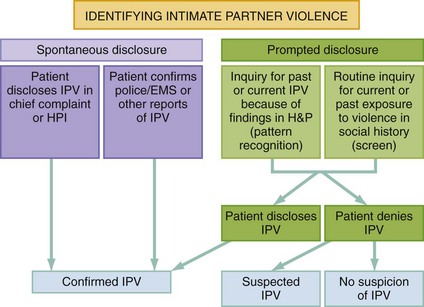

IPV is identified through disclosure or suspected based on pattern recognition. Disclosure is either spontaneous or prompted and yields a confirmed diagnosis (Fig. 68-3). A patient may spontaneously disclose IPV in the chief complaint or during the history of the presenting illness. While being triaged, a patient might state in response to a question as to why she came to the ED, “I was punched in the nose by my husband.” This is an example of spontaneous disclosure of IPV. Similarly, a patient being evaluated for decreased hearing might respond to a question about when the symptoms began, saying, “Ever since my partner slapped me across my ear.” A prompted disclosure of IPV occurs when the patient reveals or affirms IPV when asked by the HCP. The HCP may ask about past or present IPV in the process of routine inquiry, such as in the social history, or may consider IPV in the differential diagnosis of the presenting problem based on pattern recognition. For example, for a patient with multiple ED visits for minor trauma with a history of depression and suicide attempt, the HCP might ask, “With your history of depression, previous suicide attempt, and multiple episodes of injury, I was wondering if your home situation was stressful or unsafe, perhaps because of a partner who threatens or hurts you; is this true for you?” A patient who has a pattern of signs and symptoms suggestive of IPV should be asked about current or past threats or violent injury, which may lead to a prompted disclosure of IPV by the patient.

Is There an Effective Screen for Intimate Partner Violence Identification?

Because of the high prevalence rates of IPV in health care settings and the varied presentations of patients to the health care setting, numerous professional medical organizations,111 regulatory bodies, and advocacy organizations have recommended that patients be assessed to identify those who are experiencing IPV.112 In a recent report from the Institute of Medicine, IPV screening and counseling were recommended as essential preventive services and are now included as part of health care reform under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.113 The term screening is used in the IPV literature to refer to a process of asking about past or current exposure to violent or abusive behavior regardless of whether the patient is symptomatic or not. In IPV, there is no gold standard test for diagnosis, and, contrary to other health care screens, a screen for IPV relies on volition or the patient’s willingness to be truthful, which in turn depends on the degree of trust or safety the patient feels at the time of the screen. In 2013, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) reported on its evaluation of the evidence regarding screening for family violence and IPV in the health care setting. The report stated that there was adequate evidence that available screening instruments can identify current and past abuse or increased risk for abuse, and several instruments were both highly sensitive and specific. The USPSTF recommended that asymptomatic women of childbearing age be screened for IPV and that women who screen positive be provided or referred to intervention services. This recommendation was given a “B” grade, meaning there is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.114 The USPSTF found adequate evidence that effective interventions can reduce harm and adequate evidence that the risk for harm from screening or interventions is no greater than small. Houry did not find any adverse effects from questioning patients about IPV.115 In another study of 36 women interviewed after ED screening and intervention, 97% perceived screening as nonthreatening and safe. The women did not perceive any increased risk of physical harm and believed that routine assessment for IPV was essential to “stopping it from happening.”116

Failure to consider IPV may lead to misdiagnosis, inappropriate evaluations, excessive costs, and increased morbidity and mortality. In a retrospective chart review of 1884 women with a diagnosis of IPV, 50% had one or more visits to the ED before the diagnosis was made, and 72% had at least one visit because of injury; a third of the prior injuries were to the head, face, and neck.117 Rhodes and colleagues confirmed the lack of identification of IPV patients in the ED. From 993 police reports of IPV with female victims, 785 (79%) had at least one ED visit over a 4-year study period. The ED records failed to document any history of IPV in 73% of the records, and, of note, 78% of the visits were for medically related complaints.118

Routine inquiry about IPV may be conducted with a person-to-person interview or written or computerized questionnaires, and several studies have questioned women as well as IPV patients and found support for this practice.107,119–122 Routine inquiry may also be preventive, by increasing the patient’s awareness of the impact of IPV on health, decreasing the violence if referrals and interventions are provided, or lessening the impact of sequelae of violence.119,123 The inquiry may consist of a few questions about IPV or may be part of a larger health risk assessment.

When conducting a person-to-person interview, framing statements can be helpful. These statements help to normalize the questions about IPV and make them seem routine and not prejudicial (e.g., “Because of the impact of violence on women’s health, I ask all my female patients these questions”). Inclusive terms such as partner are preferred. In addition, the HCP should include appropriate use of both direct and indirect questions (e.g., “Were you hit or hurt?” [direct] or “Is there anything else you would like to tell me?” [indirect]). Rhodes and colleagues found that when the HCP asked at least one additional related question, patients were more likely to disclose abuse.123 If an additional question was asked about calls to the police to respond to a fight at home, then approximately a third more cases of IPV were identified.124 Brief instruments for use in asking about IPV are preferred by some HCPs, as they find standard questions easier to ask and remember. The Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) (Box 68-1) and Partner Violence Screen (PVS) (Box 68-2) are brief instruments for clinical use.125,126 The AAS has been validated in a variety of clinical settings, in multiethnic populations, and in Spanish. The PVS was developed and validated in the ED.

An extensive list of IPV assessment tools is provided in compendiums published by the CDC.127,128 Ultimately, whether the routine inquiry is verbal, written, or computerized, the HCP will need to have an individualized conversation with the IPV patient, being sensitive to the presenting medical problems, race and ethnicity, language barriers, cultural beliefs, gender, and sexual orientation. A successful encounter with an IPV patient or a suspected IPV patient is one in which the patient is treated with compassion, feels safe, and is provided with information, resources, and referrals regardless of whether or not she discloses IPV.

Although several questionnaires have been validated for use in identifying IPV, most have been validated for use only with female patients and with select populations and clinical situations. One study attempted to validate two common tools used in women—the HITS (hurt, insult, threaten, scream) tool and the PVS—and found them to be inaccurate for use in men, so further study is needed about screening men for experiences of violence.129 Furthermore, HCPs will be able to identify IPV with a questionnaire only if the patient chooses to disclose IPV at that particular time.

Management

Initial Assessment of Intimate Partner Violence

Once IPV has been identified, the following questions need to be asked by the IPV response team:

• What are the nature, scope, and consequences of the abuse in terms of its impact on physical and mental health?

• What is the level of danger and risk of a lethal outcome?

• What strategies have been tried, and what are possible sources of support or major barriers that need to be addressed today to assist patient safety?

• If there are children, is the parent becoming concerned for the children’s safety and well-being?

• How does the patient view his or her current situation and desire for change?

The assessment then directs the intervention (Table 68-1).

Table 68-1

Five Components of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Assessment

| ASSESSMENT ISSUE | TOPIC TO EXPLORE OR CONSIDER | IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION |

| Nature, scope, and consequences of abuse | Types of abusive behaviors: physical, sexual, emotional, financial Continued problems from prior injuries? Possibility of pregnancy or sexually transmitted infection from coerced or forced sex? Is the victim being physically or psychologically stalked? |

Directs the physical and forensic examination and any additional imaging or laboratory assessment or any needs for referral to appropriate care. |

| Danger assessment | Threats of homicide or suicide, battering during pregnancy, access to a firearm, previous strangulation, and others | Patient may be unaware of the danger. If patient is at risk for fatal outcome, obtain additional consultation and explore with the patient the possibility of contacting police, obtaining an emergency protective order, or seeking emergency placement in a shelter or other safe haven. |

| Strategies and barriers to greater safety | Are there family members or friends to confide in or a place to go in an emergency? Are there any cultural or religious barriers to consider? Does the patient have a source of income, any money, health insurance, and so on, if she or he decided to separate? Does he or she understand his or her legal rights? |

Many IPV community agencies provide individual and peer counseling, legal advice, and job training to help the victim gain confidence, and support to make changes to become safer and healthier. |

| Safety of children | Are any of the children showing signs of distress, such as behavior change at home, deterioration in school performance, depression, or acting out behavior? Are they harshly punished or verbally berated, or is there any possibility of sexual abuse? | A judgment should be made as to whether children are endangered or also being victimized, and if so, child protective services should be notified. |

| Process of change | How does the patient perceive the relationship? Is there a sense that the relationship may not be healthy or safe? Is the patient considering options? Has the patient tried to make a change or separate? Does the patient want immediate assistance for self and children? | Victim intervention can be tailored to the victim according to his or her stage in the change process as determined in the assessment. It is possible to use the brief negotiated interview to effect movement from one stage to another. |

In addition to understanding the nature and scope of the abuse experienced by the patient, the consequences need to be determined. These may be physical, such as chronic symptoms of TBI, or the patient may be experiencing mental health sequelae, such as PTSD, depression, or suicidal ideation. Houry has developed a brief mental health assessment tool for IPV patients that can be helpful in determining which patients have more severe mental health symptoms and therefore need more immediate referral to a mental health specialist.130

Assessing for risk of a lethal outcome has been extensively researched. Twenty risk factors have been validated as highly associated with an IPV homicide. Campbell and colleagues, in a multicity, retrospective, case-controlled study that used police files, surrogate interviews, and survivor interviews, compared case histories involving fatal and nearly fatal violence with the case histories of women who had been physically abused but without a life-threatening assault and developed a danger assessment tool with demonstrated predictive validity.131 Variables that significantly differentiated fatal and nearly fatal cases from controls became the elements of the danger assessment. Some of these elements include stalking and harassment of the victim, estrangement (physical or legal separation), perpetrator access to a gun or prior threats with a gun, history of forced sex, and physical abuse during pregnancy. A shorter instrument of just five questions has since been developed using stepwise logistic regression analysis; the questions are as follows:

• Has the physical violence increased in frequency or severity over the past 6 months?

• Has he ever used a weapon or threatened you with a weapon?

• Do you believe he is capable of killing you?

A positive answer to any three questions has a sensitivity of 83% (95% CI, 70.6-91.4%) and specificity of 56% (95% CI, 50.8-61.8%).132

Assessing risk factors for a possible fatal outcome is good medical care and may be protective. In one study, 54% of women killed and 45% of victims of attempted homicide did not accurately perceive their risk of being killed by their partner.20 However, Cattaneo found that women were more likely to be right than wrong in their assessment of risk for revictimization. Women seeking help for IPV (N = 246) rated the likelihood of reabuse in the coming year, and 18 months later they were reinterviewed. True positives, women who accurately predicted violence, were more likely to be experiencing stalking behaviors; false negatives, women who inaccurately predicted violence, were more likely to be in a relationship where substance abuse was a factor.133 In addition, as perceived danger increases, the physical and mental health consequences for the patient also worsen, as demonstrated in a follow-up study of 216 of 548 patients who disclosed IPV victimization and completed both a health assessment and a danger assessment.134

Clinical Intervention

System Readiness

EDs can take advantage of a tool developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to assess whether processes are in place to respond to IPV.135 The tool addresses (1) hospital policies and procedures, (2) the physical environment, (3) the cultural environment, (4) provider education, (5) screening and safety assessment, (6) documentation, (7) intervention services, (8) evaluation and quality improvement measures, and (9) collaborative agreements. Inter-rater reliability was very high (Cronbach’s α ranging from .97 to .99 in the experienced coders and .96 to .99 in the inexperienced coders). The instrument can be used for assessment and to set benchmarks for quality improvement.

Three models of system intervention have been identified, and they may be blended in various ways: Advocacy Partnering, Forensic Medicine, and a Specialty Care Model.136 The Advocacy Partnering Model is based on negotiated agreements between health clinics or hospitals and community IPV service providers. Trained peer counselors respond to provide bedside or telephone consultation, speaking directly with patients and providers to conduct a needs assessment and plan for initial intervention or, in some places, for ongoing case management and more chronic care. The Forensic Medicine Model relies on nurses or physicians who have received advanced training in the documentation, storage, and retrieval of physical evidence; forensic photography; presentation of evidence in the courtroom; and expert interpretation of findings. Bedside IPV peer counselors also assist the patient just as they do for victims of sexual assault. In the Specialty Care Model, patients can be referred to clinical experts or centers that specialize in trauma recovery. In pediatrics, child abuse is now a recognized subspecialty given the scope of both knowledge and skills required for the care of abused children. Some departments (e.g., behavioral health) or individuals have established IPV care as an area of expertise, and once the patient is medically stabilized, referral for bedside or delayed consultation is made just as for any other ED problem.

Intervention in the Emergency Department

IPV is a socially stigmatized issue and, as such, requires concerted effort on the part of the clinician to establish trust and convey empathy. An empathic and nonjudgmental assessment and respectful discussion of options with a trusted HCP are postulated to have potential therapeutic benefits in and of themselves. The assessment guides decision-making regarding the needs for immediate or delayed intervention. The HCP will encounter five levels of patients, based on IPV exposure and risk. Each level has guidelines for varying intervention strategies and critical elements for documentation (Table 68-2).

Table 68-2

Intervention Strategies Based on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Exposure and Risk Level

| PATIENT TYPE BASED ON ASSESSMENT | INITIAL INTERVENTION STEPS | CRITICAL DOCUMENTATION FOR THE ENCOUNTER |

| I. No history of IPV or suspicion of abuse | Provide basic message that IPV is a health problem | “No history of IPV; no suspicion of IPV” |

| II. Prior history of IPV but no current exposure | Assess for sequelae of prior abuse; provide educational message that patient is at risk of future IPV relationship | Add history of IPV to problem list (can be coded as a V-code); describe medical and mental heath impact and any referrals made |

| III. Recent or current abuse but no injuries and no elements on danger assessment | Assess for sequelae of abuse; provide referrals to IPV resources | Add IPV to problem list; describe health sequelae from abuse; note referral for urgent follow-up provided to patient |

| IV. Recent or current abuse with injuries or positive findings on danger assessment | Crisis bedside consultation by social services or IPV advocate; discuss possibility of an order for protection; notify police if required by law | Add IPV to problem list; describe health sequelae; summarize follow-up plan as outlined by social services or IPV advocate; complete mandatory reports; describe injury findings using narration, diagrams, and photographs |

| V. Suspicion of current abuse but patient denies IPV | Provide basic message that IPV is health problem; request bedside consultation by social services or IPV advocate; provide referrals to IPV resources | Document IPV as a suspected health problem; note that bedside consultation was done and resources were provided; if injured, describe injury findings using narration, diagrams, and photographs |

Most IPV intervention for victims centers around theoretic constructs of the Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory, and self-efficacy. The Health Belief Model’s core assumption is that a person will take a health-related action if the individual believes that a negative health condition can be avoided (perceived susceptibility), has a positive expectation about taking the recommended action (perceived benefit), and believes that he or she can successfully take the recommended action (self-efficacy).137 Both perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy have been demonstrated to be strong predictors of behavioral change. Social Cognitive Theory has a strong emphasis on cognition and posits that cognitions change over time. According to this theory, people develop perceptions about their own abilities and characteristics that guide their behavior by determining what they try to achieve. One’s perceived self-efficacy for a given behavior dramatically affects one’s self-motivation for performing that behavior. These are the theoretic constructs that underlie interventions for IPV victims.

Some victims are receptive to provider recommendations or referrals, and some may not be, depending on their readiness for change. The stages of change—precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance—are well described. Women who normalize physical violence or emotional abuse as expected behavior are in a precontemplation phase and may only be ready to consider the negative health consequences, moving them to a contemplation stage; however they are unlikely to consider separation from the abuser, as that would be a three-step advancement to action in the stages of change. Asher reported that women who screened positive for IPV in ED visits (N = 101) populated each stage of change, but most were in the early stages of precontemplation and contemplation.138

Safety planning is a harm reduction intervention in that the patient may be returning to a dangerous situation, but certain behavior changes may contribute to a less negative outcome. Needle exchange programs are examples of a harm reduction effort to prevent additional illness in intravenous drug users. Strategies for avoiding further harm may be both protective and empowering. Planning for safety during a violent outburst (getting to a room with a lockable door and exterior window) or for immediate escape (placing a suitcase in the safekeeping of a trusted other with clothes, documents, and extra cash) are examples of harm reduction safety planning that can be developed with the patient by the clinician or the bedside IPV peer counselor.139

In the past 20 years, community IPV agencies or victim advocacy organizations have been developed in every state to provide services for IPV victims and their children. The federal Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) provides considerable funding to support these service providers. Although most of the time patients are referred to such agencies for follow-up, more and more agencies now respond to health care requests with bedside, telephone, or telemedicine consultation. Information about what agencies are available in a specific community is easily available through the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) or (TTY) 1-800-787-3224. Sullivan examined the effect of community-based advocacy services after a shelter stay and found that at 2-year follow-up, IPV victims who had received the advocacy intervention experienced less physical abuse, had an increased quality of life, and accessed more community IPV resources than the control group. Of note, 25% of the intervention group, compared with 10% of the control group, had experienced no further violence after the intervention.140

Bedside consultation was implemented in EDs in Kansas City, Missouri, and analysis showed that patients who had not called the police for the index event and received bedside counseling with a victim advocate were more likely than those who were only given a handout with resources, to call the police for a subsequent event (39% vs. 18% [95% CI, 1-40%]), seek emergency shelter (28% vs. 11% [95% CI, 6-27%]), or obtain counseling (15% vs. 1% [95% CI, 7-21%).141 In a study by McFarlane, telephone follow-up calls for harm reduction counseling resulted in the increased adoption of safety behaviors that remained even 2 years after counseling ended.142 In one study that involved follow-up of 157 of 350 patients who had received a brief ED intervention, 96% of the patients perceived that their safety had improved postintervention. However, without a control group, it is not possible to attribute the improvement to the intervention.143 One randomized, controlled trial of a brief ED screening, education, and referral intervention in New Zealand found no difference in short-term recurrence of violence between treatment and control groups.144

Interventions and Referrals for Perpetrators

Interventions for IPV perpetrators have not been shown to be as effective as hoped. The problem is that a “one-size-fits-all” approach appears to be inadequate for the known typologies of violent offenders. The current treatment modalities are organized according to etiologic theories145: (1) cognitive-behavioral treatment focuses on deficient thought patterns such as rigid beliefs and limited problem-solving; (2) psychodynamic treatment addresses unresolved physical and emotional trauma; and (3) feminist models focus on educational efforts to increase awareness of oppressive, sexist attitudes and foster nonoppressive, egalitarian behaviors. Conjoint treatment for couples remains controversial, and the primary objections center around safety concerns for victims. Right now, patients who disclose histories of interpersonal violence, with partners, acquaintances, or strangers, should all be referred to social services for further evaluation and appropriate referral. Once a perpetrator has been arrested, the criminal justice system does not generally conduct comprehensive assessments, so offenders do not have as many treatment options. Unfortunately, that usually means that recidivism for offenders is quite high.

Cultural Issues

• Language interpreters should be professionals and non–family members, with some training and background in the dynamics of IPV. There are some languages that do not readily translate the phrases or the concepts related to family violence.

• Immigrant victims fear deportation for themselves should they disclose IPV and in most cases fear deportation for their partners. There are protections within VAWA that allow a victim to remain in this country even if his or her legal spouse and/or sponsor is deported.

• Some victims of color may be reluctant to contact law enforcement because of apprehension regarding racism. Although the desire to be safe and free from violence is real, the fear of unfair treatment for the partner is also real.

• Lower rates of disclosure have been documented in Latina women. Gender role ideologies, traditional beliefs about marriage, familism, and taboos against talking about sex are some of the reasons suggested for lower rates of disclosure in this cultural group.146

Interface with the Criminal Justice System

IPV is considered to be a public safety issue. As such, domestic violence is a crime in all 50 states, as is spousal rape. Criminal justice remedies can be helpful for some patients. Mandatory arrest policies provide a “cooling off” period that gives patients time to implement safety plans or seek safer shelter. Orders of protection may be useful in helping victims to feel safer, although at least one study among African Americans reported heightened fear of retaliation when protective orders were obtained.147 Protective orders can be written such that they allow for immediate search and seizure of firearms, and protective orders link into databases that restrict firearm purchase by perpetrators. Finally, crime victims’ restitution programs can help patients buy and install home security systems, change residences, or pay for uncompensated medical or mental health care for victims and/or their children.

In most states, HCPs negotiate with patients to determine how and when to contact law enforcement. However, in some states, HCPs are required by law to report any patients who have sustained injury with a weapon, and a few states require reports to law enforcement, regardless of patient consent, for any patient who has injuries that appear to be intentionally inflicted. The most restrictive reporting mandates have been implemented because the IPV victim is perceived as a “vulnerable person,” just as in child and elder abuse, and proponents advocate that victims be assisted with the full resources of the health and safety systems. Unfortunately, there is neither sufficient evidence for nor sufficient evidence against laws mandating reporting by health professionals to law enforcement in the case of IPV. There are survey data that reveal physician anxiety about proceeding without patient consent,148 and there are mixed results from victims themselves, with some seeing the law as helpful and others seeing it as potentially harmful.149 A qualitative study based on interviews with women found victims to be generally supportive of mandatory reporting to law enforcement and did not perceive that the law placed them or their children at higher risk.150

Ethical Considerations

• What if the principal insured party is the abusive partner? What procedures are in place between the provider and the third-party insurer to protect the confidentially and safety of IPV victims?

• Are there any routine follow-up processes in place, such as patient satisfaction surveys, that might inadvertently result in contact with a patient and alert the abusive partner about a health care visit?

• What if a minor discloses IPV occurring in the home and the abusive parent seeks access to the medical record?

• If IPV is noted on the medical record, could this be grounds for health or home insurance companies to cancel insurance?

• What if the patient discloses IPV as the cause of injuries and now the provider, by law, must notify law enforcement of possible criminal behavior?

If a patient discloses violent or abusive behavior, the physician operates under obligation of confidentiality and cannot disclose to police unless required by law. The duty of a citizen to report criminal behavior is a communal value and appears to clash with the duty regarding maintain patient confidentiality. However, this duty regarding confidentiality is also a communal value, and unless it is overridden by legal mandates, the HCP cannot report criminal behavior but can warn intended victims if there is a perceived threat to their safety (Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California [1976] 17 Cal. 3d 425).151,152

Informed Consent and Autonomy

IPV patients are not always free to act of their own will in health care decision-making. Coercive decision-making is not autonomous decision-making. Fear may be so profound that decision-making is impaired, thus jeopardizing informed consent. In a Montana malpractice suit, the ED physician and hospital were sued for failure to accurately diagnose and failure to provide for patient safety when an IPV patient was discharged to home only to sustain devastating physical injury by her abusive partner.153 According to the plaintiff’s attorney, the ED physician testified in deposition that IPV was discussed and safety issues addressed; however, the patient testified that she was at the hospital under duress and her decision-making capacity was diminished by the coercive threats of her boyfriend to inflict further harm should she disclose the IPV (C. Mitchell, personal communication with D. Buxbaum, September 27, 2002). Although this case was settled before court judgment, the coercive nature of extreme fear and its impact on informed consent and clinical decision-making are challenges for both clinicians and ethicists.

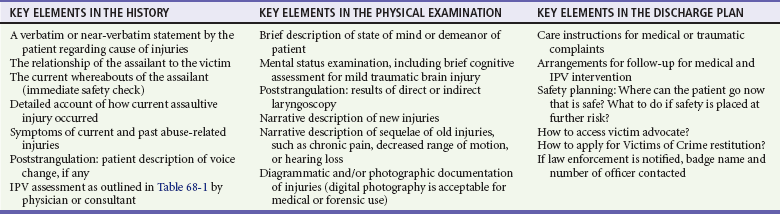

Documentation

Table 68-3 lists the key elements in the history of the presenting illness, physical examination, and discharge instructions that should be addressed and documented.

Forensic Documentation

The medical record becomes a forensic record when it becomes part of a legal process. The word forensic means “pertaining to the law.” A medical record is likely to be more focused and less detailed than a formal forensic examination. Sexual assault and child abuse patients have, for many years, benefited from the additional service and care of medical forensic teams that can coordinate with law enforcement and then follow meticulous protocols to collect and document detailed findings. Other members of the team can provide interventions for medical and mental health needs and establish care for longer-term needs. These programs have served as models for IPV forensic care. California has developed clinical guidelines, a forensic protocol, and a form for the forensic medical examination of victims, which is available online (www.ccfmtc.org/forensic.asp). Many law enforcement agencies now contract with forensic medical examiners to conduct the forensic examination, collect physical evidence, and present courtroom testimony. Forensic examinations are done only with the full consent of patients, which differs from some state laws regarding reporting. Forensic examinations are usually time-consuming and detailed and are done under contract or reimbursed through Victims of Crime funding. In contrast, mandatory reporting to law enforcement or public health departments usually only captures critical elements either for public health surveillance or to alert public safety departments of a possible violent crime.

References

1. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002.

2. Saltzman, LE, Fanslow, JL, McMahon, MJ, Shelley, GA. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements. Atlanta, Ga: Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Disease Prevention and Control; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 1999.

3. Truman, JL, Criminal Victimization, 2010. Washington, DC:Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2011. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv10.pdf.

4. Catalano, S, Intimate Partner Violence, 1993-2010. Washington, DC:Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2012. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipv9310.pdf.

5. Black, MC, et al, The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA:National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/NISVS.

6. Tjaden, P, Thoennes, N, Allison, CJ. Comparing violence over the life span in samples of same-sex and opposite sex cohabitants. Violence Vict. 1999;14:413–425.

7. Black, MC, Breiding, MJ. Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—United States, 2005 (Reprinted from MMWR, 2008; 57:113-117). JAMA. 2008;300:646–647.

8. Breiding, MJ, Ziembroski, JS, Black, MC. Prevalence of rural intimate partner violence in 16 U.S. states, 2005. J Rural Health. 2009;25:240–246.

9. Koin, D. Intimate partner violence in the elderly. In: Mitchell C, Anglin D, eds. Intimate Partner Violence: A Heath-Based Perspective. New York: Oxford University, 2009.

10. Mouton, CP, et al. Prevalence and 3-year incidence of abuse among postmenopausal women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:605–612.

11. Anglin, D, Sachs, C. Preventive care in the emergency department: Screening for domestic violence in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1118–1127.

12. Dearwater, SR, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner abuse in women treated at community hospital emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;280:433–438.

13. McFarlane, J, Greenberg, L, Weltge, A, Watson, M. Identification of abuse in the emergency departments: Effectiveness of a two-question screening tool. J Emerg Nurs. 1995;21:391–394.

14. Biroscak, BJ, Smith, PK, Roznowski, H, Tucker, J, Carlson, G. Intimate partner violence against women: Findings from one state’s ED surveillance system. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32:12–16.

15. Abbott, J, Johnson, R, Koziol-McLain, J, Lowenstein, SR. Domestic violence against women: Incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA. 1995;273:1763–1767.

16. Mechem, CC, Shofer, FS, Reinhard, SS, Hornig, S, Datner, E. History of domestic violence among male patients presenting to an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:786–791.

17. 10 Leading Causes of Death, United States, 2010, All Races, Females. Atlanta, Ga:National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leading_causes_death.html.Accessed.

18. Karch, D, Dahlberg, L, Patel, N. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violence Death Reporting System, 16 States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59:1–50.

19. Homicide Trends in the United States. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2004.

20. Campbell, JC, Glass, N, Sharps, PW, Laughon, K, Bloom, T. Intimate partner homicide: Review and implications of research and policy. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:246–269.

21. Wadman, M, Muelleman, R. Domestic violence homicides: ED use before victimization. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:689–691.

22. Sharps, P, Koziol-McLain, J. Health care providers’ missed opportunities for preventing femicide. Prev Med. 2001;33:373–380.

23. Max, W, Rice, DP, Finkelstein, E, Bardwell, RA, Leadbetter, S. The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Violence Vict. 2004;19:259–272.

24. Ulrich, YC, et al. Medical care utilization patterns in women with diagnosed domestic violence. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:9–15.

25. Rivara, F, Fishman, P, Bonomi, A. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:89–96.

26. Rivara, F, Fishman, P, Bonomi, A. Intimate partner violence and health care costs and utilization for children living in the home. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1270–1277.

27. McCauley, J, et al. The “battering syndrome”: Prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:737–746.

28. Coker, AL, Smith, PH, Bethea, L, King, MR, McKeown, RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:451–457.

29. Whitfield, CL, Anda, RF, Dube, SR, Felitti, VJ. Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18:166–185.

30. Nosek, MA, Howland, CA, Hughes, RB. The investigation of abuse and women with disabilities. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:477–499.

31. Caetano, R, Cunradi, C, Clark, C, Schafer, J. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11:123–138.

32. Kyriacou, DN, et al. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1892–1898.

33. Honeycutt, T, Marshall, L, Weston, R. Toward ethnically specific models of employment, public assistance, and victimization. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:126–140.

34. Coker, A, Sanderson, M, Fadden, M, Pirisi, L. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual and psychological battering. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:553–559.

35. Bassuk, EL, et al. The characteristics and needs of sheltered homeless and low-income housed mothers. JAMA. 1996;276:640–646.

36. Menjivar, C, Salcido, O. Immigrant women and domestic violence: Common experiences in different countries. Gend Soc. 2002;16:898–920.

37. Frye, V, et al. The role of neighborhood environment and risk of intimate partner femicide in a large urban area. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1473–1479.

38. Ochs, H, Neuenschwander, M, Dodson, T. Are head, neck and facial injuries markers for domestic violence? J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;127:757–761.

39. Muelleman, R, Lenaghan, P, Pakiese, R. Battered women: Injury locations and types. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:486–492.

40. Le, BT, Dierks, EJ, Ueeck, BA, Homer, LD, Potter, BF. Maxillofacial injuries associated with domestic violence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1277–1283.

41. Davis, KE, Coker, AL, Sanderson, M. Physical and mental health effects of being stalked for men and women. Violence Vict. 2002;17:429–443.

42. Seedat, S, Stein, M, Forde, D. Association between physical partner violence, posttraumatic stress, childhood trauma, and suicide attempts in a community sample of women. Violence Vict. 2005;20:87–98.

43. Boyle, A, Jones, P, Lloyd, S. The association between domestic violence and self harm in emergency medicine patients. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:604–607.

44. Hamberger, L. Risk factors for intimate partner violence perpetration: Typologies and characteristics of batterers. In: Mitchell C, Anglin D, eds. Intimate Partner Violence: A Health-Based Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

45. Ernst, AA, et al. Adult intimate partner violence perpetrators are significantly more likely to have witnessed intimate partner violence as a child than nonperpetrators. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:641–650.

46. Mauricio, AM, Gormley, B. Male perpetration of physical violence against female partners: The interaction of dominance needs and attachment insecurity. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16:1066–1081.

47. Brookoff, D, O’Brien, KK, Cook, CS, Thompson, TD, Williams, C. Characteristics of participants in domestic violence: Assessment at the scene of domestic assault. JAMA. 1997;277:1369–1373.

48. Hutchison, IW, Hirschel, JD. The effects of children’s presence on woman abuse. Violence Vict. 2001;16:3–17.

49. Ernst, A, Weiss, S, Enright-Smith, S. Child witnesses and victims in homes with adult intimate partner violence. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:696–699.

50. Curry, MA, Doyle, BA, Gilhooley, J. Abuse among pregnant adolescents: Differences by developmental age. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1998;23:144–150.

51. Grimstad, H, Backe, B, Jacobsen, G, Schei, B. Abuse history and health risk behaviors in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:893–897.

52. Morland, LA, Leskin, GA, Block, CR, Campbell, JC, Friedman, MJ. Intimate partner violence and miscarriage: Examination of the role of physical and psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:652–669.

53. Neggers, Y, Goldenberg, R, Cliver, S, Hauth, J. Effects of domestic violence on preterm birth and low birth weight. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:455–460.

54. Leone, JM, et al. Effects of intimate partner violence on pregnancy trauma and placental abruption. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:1501–1509.

55. Coker, A, Sanderson, M, Dong, B. Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18:260–269.

56. Janssen, PA, et al. Intimate partner violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1341–1347.

57. Anda, RF, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–186.

58. Felitti, VJ, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258.

59. Brown, DW, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev M. 2009;37:389–396.

60. Miller, E, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of physical violence in adolescent dating relationships. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:1006–1013.

61. Duke, N, Pettingell, S, McMorris, B, Borowski, I. Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e778–e786.

62. Tajima, E. The relative importance of wife abuse as a risk factor for violence against children. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:1383–1398.

63. Edleson, JL. The overlap between child maltreatment and woman battering. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:134–154.

64. Kerker, BD, Horwitz, SM, Leventhal, JM, Plichta, S, Leaf, PJ. Identification of violence in the home, pediatric and parental reports. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:457–462.

65. Spears, L, Building Bridges between Domestic Violence Organizations and Child Protective Services. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence; 2000. http://www.vawnet.org/Assoc_Files_VAWnet/BCS7_cps.pdf.

66. Casanueva, C, Martin, SL, Runyan, DK. Repeated reports for child maltreatment among intimate partner violence victims: Findings from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:84–93.

67. Kuelbs, C. The impact of intimate partner violence on children. In: Mitchell C, Anglin D, eds. Intimate Partner Violence: A Health-Based Perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009.

68. Bogat, GA, DeJonghe, E, Levendosky, AA, Davidson, WS, von Eye, A. Trauma symptoms among infants exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:109–125.