109 Intestinal Obstruction and Malrotation

Etiology and Pathogenesis

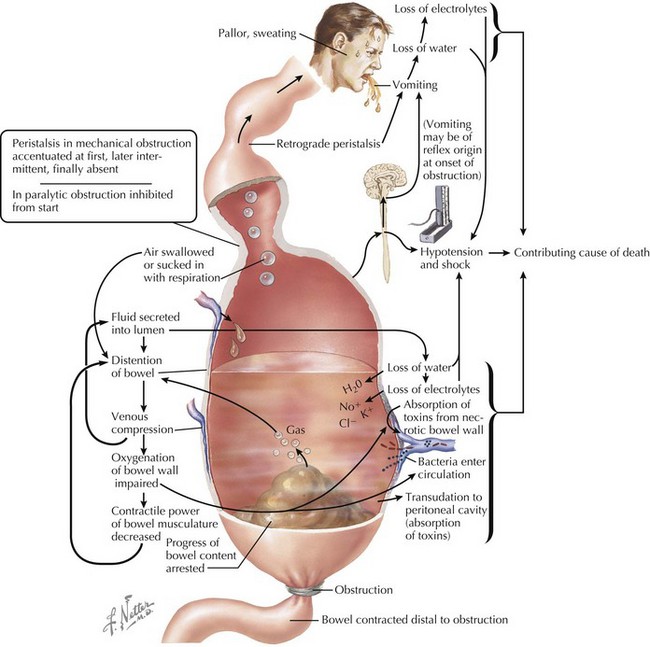

The many etiologies that cause intestinal obstruction ultimately result in a final common pathophysiologic pathway (Figure 109-1). Anything that prevents forward progress of intestinal contents sets into motion this sequence of events, leading to worsening distension, vomiting, and systemic dysfunction. Not only do the resulting dehydration and electrolyte imbalances create significant complications, bacterial proliferation within the static intestinal contents and compromised mucosal integrity set the stage for bacterial translocation across the intestinal wall, with consequent bacteremia and sepsis.

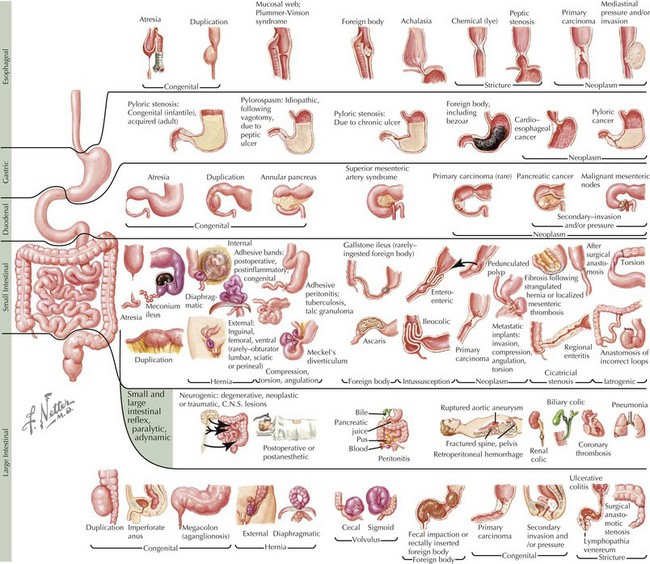

Although many disorders may cause obstruction (Figure 109-2), they can be summarized by several pathophysiologic categories that aid in constructing a rational differential diagnosis.

Intrinsic Decrease in Lumen Caliber

Acquired Defects

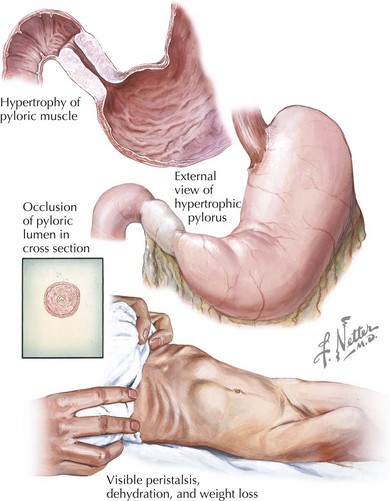

Chronic bowel inflammation can, over time, lead to narrowing of the lumen. An important example is Crohn’s disease, in which there is discontinuous full-thickness bowel inflammation anywhere from the mouth to the anus (see Chapter 110). Over time, inflamed areas may stricture and obstruct. Another example of this is eosinophilic esophagitis, an entity that lies within the spectrum of food allergies and atopic disease. Because of persistent eosinophilic inflammation in the presence of the offending antigen, the esophagus can eventually stricture over time, leading to dysphagia and the need for esophageal dilatation to relieve the obstruction. Malignancy, although relatively uncommon in children compared with adults, is another important cause of decreased lumen caliber. For example, the GI tract is the most common extranodal site affected in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Infiltration of the bowel wall by tumor leads to decreased effective luminal diameter and a higher risk of obstruction. Achalasia causes functional esophageal obstruction caused by aperistalsis and inadequate lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. An example of gastric outlet obstruction caused by decreased diameter is hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, a disease primarily affecting infants in the first few months of life in which smooth muscle hypertrophy leads to occlusion of the pylorus (Figure 109-3).

Defects in Bowel Arrangement

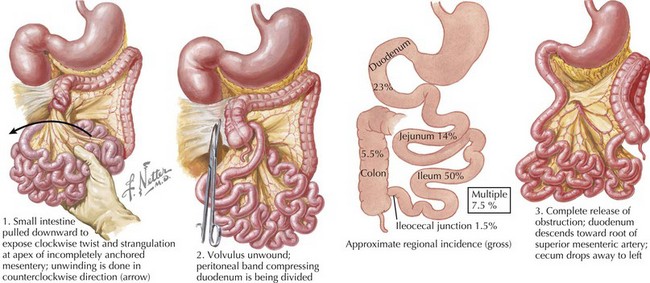

Malrotation is an important entity that clinicians must be aware of when evaluating intestinal obstruction of unknown etiology. Malrotation is a congenital defect typically involving both the small and large intestines that occurs when the bowel assumes an abnormal spatial arrangement within the abdomen. Intestinal development is a complex, continuous process spanning the fourth fetal week to birth that takes the primitive gut, which begins as a short, straight tube, and transforms it into a long, highly specialized organ. As part of this process, the intestinal tract, after rotating 270 degrees, becomes fixed in a specific arrangement such that the duodenum ends at the ligament of Treitz in the left upper quadrant and the cecum is found in the right lower quadrant. When this final arrangement fails to take place properly, the bowel is malrotated. Although this may not result in any clinical symptoms in mild cases, the most feared complication is volvulus, a surgical emergency in which the bowel, as a result of its inappropriate positioning and lack of usual support, twists upon its mesenteric stalk, causing not only intestinal obstruction but also ischemia (Figure 109-4). Ladd’s bands, intraperitoneal fibrous bands that can encircle and obstruct the duodenum, are also associated with malrotation.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with obstruction may experience a wide range of symptoms depending on the nature and severity of the etiology. The physician’s primary responsibility at first contact with any patient is to triage the severity of illness and prevent the further progress of medical complications. Patients with obstruction may exhibit severe pain, abdominal distension (unless involvement is in the proximal GI tract), diaphoresis, stigmata of dehydration, and vomiting with inability to tolerate oral input. The patient may be tachycardic (both from pain and hypovolemia). The blood pressure can be difficult to interpret, with high values being most likely a response to pain; a normal blood pressure should not be taken as a necessarily reassuring sign without a measure of skepticism. Indeed, a normal value in the context of an ill-appearing, tachycardic patient may be indicative of compensated shock (see Chapter 2). Fever raises concerns for intestinal ischemia, perforation, and peritonitis.

There are many potential causes of GI obstruction (see Figure 109-2). However, because the clinical presentation of the patient is governed by the specific characteristics of the obstructive etiology, attention to the patient’s particular symptom complex can yield clues helpful to constructing a rational differential diagnosis. Several key questions help to organize the approach to the patient.

Does the Child Have Other Historical or Physical Examination Abnormalities?

The presence of other abnormalities may raise suspicion for particular etiologies. Trisomy 21 is one of many congenital disorders that can be associated with intestinal atresia and other anomalies such as malrotation (see Chapter 117). Heterotaxy is associated with malrotation, which can lead to Ladd’s bands and volvulus. Patients who have recently had Henoch-Schönlein purpura, an acquired form of vasculitis, are at risk for intussusception, as are those with polyps and duplication cysts (see Chapter 28). Crohn’s disease is a common cause of intestinal stenosis (see Chapter 110).

Evaluation And Management

Initial Care in the Emergency Department

Radiologic Tests

If the individual has primarily esophageal symptoms, an esophagram can delineate the site and nature of defect, as well as evaluate esophageal function (see Chapter 107). In a stable patient with small bowel obstructive symptoms, the study of choice is the upper GI series, in which the contrast is followed to the ligament of Treitz. This study assesses for malrotation or volvulus in addition to a host of other anatomic defects. It is essential that any child younger than 1 year of age with bilious vomiting must be assessed for malrotation and volvulus. A variant on the upper GI series is the upper GI with small bowel follow-through, in which the radiologist assesses the bowel to the terminal ileum. This study is inappropriate for the acute setting given the length of time required to perform the study and the need to use barium, which is required because endogenous secretions dilute water-soluble contrast as it passes through the GI tract, making it ineffective for delineating the distal small bowel. However, this is a valuable tool when the suspicion is that a defect beyond the ligament of Treitz may be causing partial small bowel obstruction.

Applegate KE, Anderson JM, Klatte EC. Intestinal malrotation in children: a problem-solving approach to the upper gastrointestinal series. Radiographics. 2006;26:1485-1500.

Grant HW, Parker MC, Wilson MS, et al. Adhesions after abdominal surgery in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:152-157.

Zerey M, Sechrist CW, Kercher KW, et al. The laparoscopic management of small-bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 2007;194:882-888.