Interpretation of the clinical examination of the cervical spine

A standardized clinical examination enables the examiner to recognize clinical patterns. He/she will easily distinguish common patterns from uncommon ones and recognize so-called ‘warning signs’ (see Ch. 9). Neck, shoulder girdle and shoulder problems are differentiated and a distinction is made between ‘mechanical’ conditions, such as disc lesions or capsuloligamentous lesions, and ‘non-mechanical’ conditions, such as rheumatological, neurological or infectious disorders.

Interpretation of the history

Pain

Localization

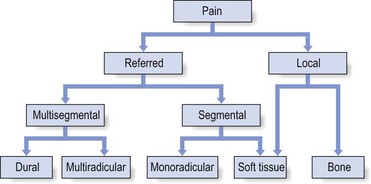

The actual site of the pain is a first rough pointer. Pain may be localized or vague, and is felt either in the neighbourhood of the lesion or at a distance (see Referred pain, Ch. 1).

Very localized pain, accurately indicated by the patient, is often a ligamentous or facet joint problem. Bony lesions also give rise to localized pain. Pain that is vaguely defined and spreads over a larger area is usually referred. It is then distal to the lesion (see Rules of referred pain, Ch. 1). Referred pain that is felt in a particular dermatome (segmentally referred) is often radicular in origin but may also result from any soft tissue lesion in the region of the neck. The source is usually an inflammation and/or compression of a mid- or lower cervical nerve root, giving rise to pain in the shoulder area (C4) or in the upper limb (C5–T2). It often indicates a discoradicular interaction, but other causes of root pain should also be considered, such as degenerative conditions or a space-occupying lesion in the radicular canal.

Pain that is felt in several adjacent dermatomes at the same time is quite common and indicates a multisegmental type of reference (see Fig. 7.1). Multisegmental pain reference may be either the result of multiradicular involvement – which is extremely uncommon in the cervical spine and should immediately arouse suspicion (see Warning signs, Ch. 9) – or the result of a discodural interaction. In the latter case other dural symptoms may also be found and the functional examination shows a clinical picture of internal derangement (see Ch. 8). It should be stressed that dural symptoms are mostly discogenic in origin but may also occur in any space-occupying lesion in the spinal canal interfering with the sensitivity or the mobility of the dura mater. Dural pain is usually felt at the lower neck, in the trapezius area and the upper scapular and interscapular region, either centrally or unilaterally. The pain may spread further, upwards to the head, face and upper neck or the mid-scapular, pectoral and axillary regions.

Fig 7.1 Reference of pain.

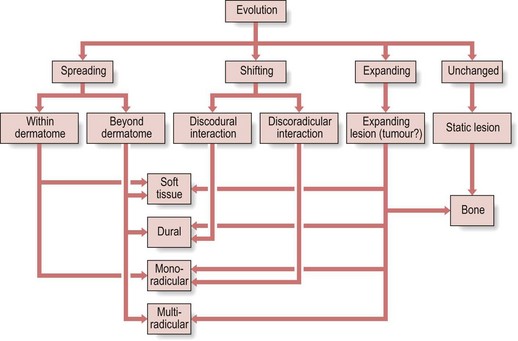

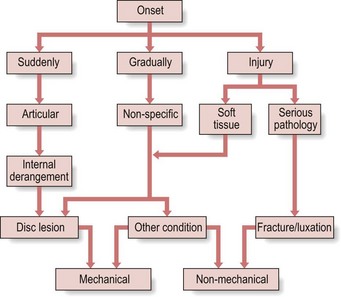

Onset (Fig. 7.2)

Pain may come on suddenly, gradually or as the result of an injury. Pain that starts suddenly is activity-related. It is a manifestation of sudden internal derangement of an intervertebral joint, mostly the result of the displacement of a discal fragment. It is then usually accompanied by sudden twinges when moving. It comes and goes in an irregular way and tends to recur. Functional examination shows the articular involvement. Pain that comes on gradually is not very informative because many different conditions begin in that way. If the pain is related to specific activities, a mechanical condition (see Ch. 8) is probable; if such a relation between symptoms and movements or postures is not found, a non-mechanical condition should be considered (see Ch. 9). If an injury is responsible for the development of the patient’s symptoms, further technical investigation will be necessary to exclude serious disorders such as fractures and luxations.

Fig 7.2 Onset of pain.

Accompanying symptoms

Coughing or sneezing that causes pain in the trapezius or scapular region is a common symptom in discodural or discoradicular interactions, although any space-occupying lesion in the spinal canal may elicit such symptoms. Pain in the arm on coughing is considered unusual and mandates a closer look: the patient could be suffering from a neurofibroma. Twinges – sudden bouts of pain resulting from movement of the head – are a typical articular symptom. They very much suggest internal derangement in the intervertebral joint – a disc protrusion. Morning pain is typical of arthritic and rheumatoid-type conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis. It also occurs in capsuloligamentous contracture following degeneration (‘the elderly man’s morning headache’ – see Ch. 8). Nocturnal pain is generally accepted as being of the inflammatory type, although mechanical pain may occur when the patient has a poor sleeping posture in which the head is put into a painful position.

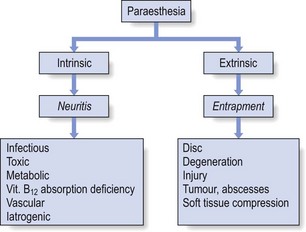

Paraesthesia

Paraesthesia is the major differential diagnostic feature distinguishing lesions in nervous tissue and other structures. This may vary from real ‘pins and needles’ to ‘numbness’ and may evolve towards a sensory deficit. If paraesthesia is mentioned and is clearly related to the lesion, a nervous disorder or a lesion affecting a nervous structure is present. The problem may be intrinsic (‘neuritis’) or extrinsic (‘entrapment’) (see Fig. 7.4).

Fig 7.4 Paraesthesia.

In nerve tissue compression three major features have to be interpreted: proximal extent, localization and behaviour. The patient has to understand clearly the difference between pain and paraesthesia because both behave differently. The lesion responsible for the development of pins and needles always lies proximal to their proximal extent; in other words, the area of paraesthesia is always felt distally to the site of compression. The localization of the paraesthesia is defined to a multisegmental area (spinal cord), a segmental area (nerve root) – dermatome – or the territory of a peripheral plexus or nerve. The behaviour of the symptoms depends on which part of the nervous system is involved and subsequently on which mechanism is active: spinal cord, nerve root, nerve trunk or nerve ending (see Complete information on pressure on nerves in Ch. 2).

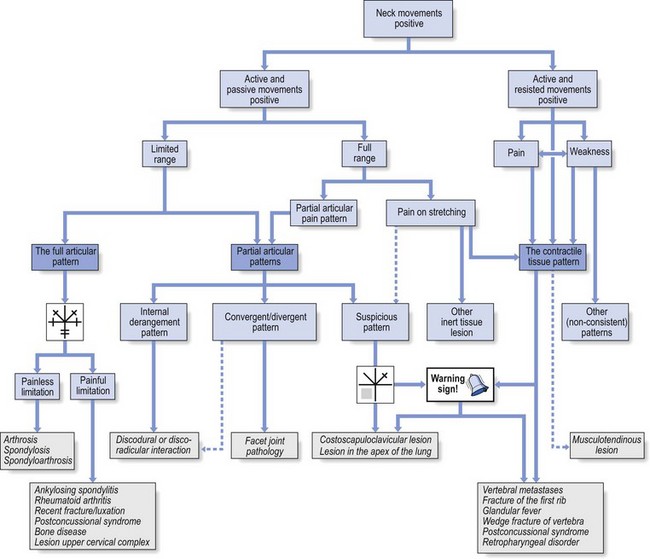

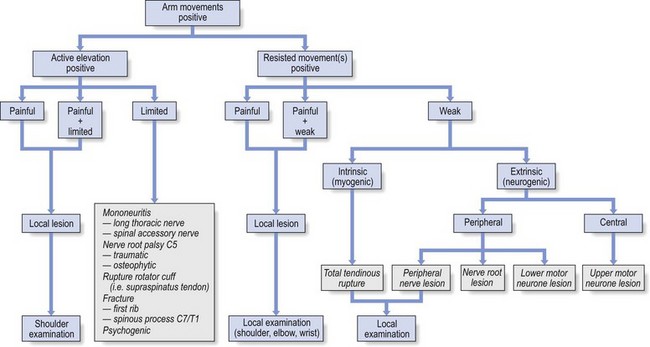

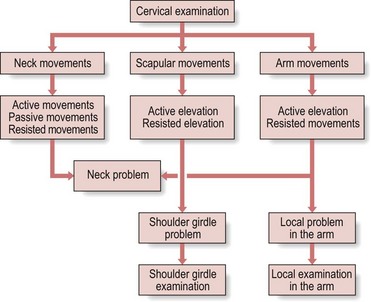

Interpretation of the functional examination

The functional examination of the cervical spine does not cause technical problems. Active, passive and resisted movements are easy to perform and easy to assess; the patient reports pain and the examiner detects limitation, changes in the end-feel and weakness. Interpretation rests on these physical findings and clinical patterns will emerge. Because the examination comprises tests at three different levels – neck, shoulder girdle and arm – it is possible to establish the level at which the lesion should be sought (Fig. 7.5). If signs are found at all three levels, it is logical to look for the lesion ‘half-way’, i.e. in the shoulder girdle.

Fig 7.5 Cervical examination.

Positive scapular movements usually point towards a lesion in the shoulder girdle, although it is possible to find slight positive signs in a disorder of the cervical spine; elevation and/or approximation of the scapulae also act as a dural sign. If a shoulder girdle problem is suspected, a complete shoulder girdle examination should follow (see online chapter Clinical examination of the shoulder girdle).

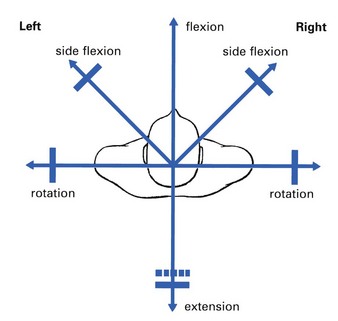

Interpretation of neck movements (Fig. 7.6)

Active and passive movements are positive

Limited movement: the full articular pattern

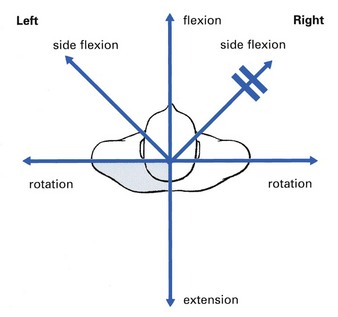

The full articular pattern at the cervical spine is no limitation of flexion, equal degree of limitation of side flexion and rotation, and some or serious limitation of extension (see Fig. 7.7).

Fig 7.7 The full articular pattern.

Limited movement: partial articular patterns

A partial articular pattern is a clear asymmetrical presentation of pain and/or limitation. This common finding usually indicates internal derangement (displacement of a disc fragment with discodural or discoradicular interaction). The complete clinical picture must, of course, be compatible with history and end-feel – see Chapter 8.

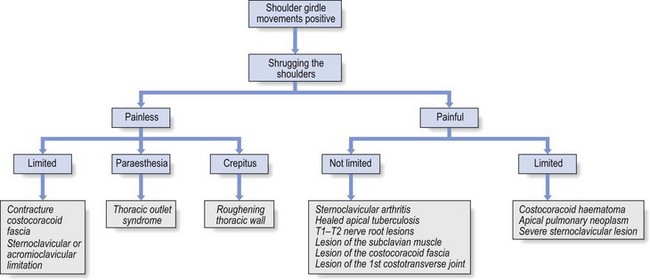

Interpretation of shoulder girdle movements (Fig. 7.9)

Fig 7.9 Shoulder girdle movements.

Pins and needles in one or both hands on sustained movement suggests the thoracic outlet syndrome. Crepitus indicates roughening of the posterior thoracic wall (see online chapter Disorders of the inert structures).