CHAPTER 69 Interposition Arthroplasty of the Elbow

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

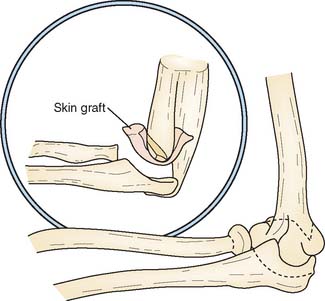

The so-called functional arthroplasty, popularized by Hass (1944),11 might be considered the predecessor of interposition arthroplasty. Functional arthroplasty is actually a variation of resection arthroplasty, except that the distal humerus is fashioned in the shape of a wedge and various types of interposed tissues may be inserted (Fig. 69-1). Hass reported a long-term satisfactory result of 73% in 15 patients, with an average follow-up period of 5.5 years. Because this is a type of resection arthroplasty, it is not surprising that 13 of the 15 procedures were in patients with previous infection.

Interposition arthroplasty has been used for treatment of arthritis involving the temporomandibular, shoulder, wrist, knee, and hip joints. Of these, the elbow has been reported as second only to the temporomandibular as the joint most amenable to the technique.13 In Europe, arthroplasty was popularized by Putti30 and by Payr.28 Schüller was the first to recommend the procedure for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.32 Various muscle flaps, pig bladder,2 fascia-fat transplants, skin, and other materials have been used as the interposing agent. In 1902, Murphy introduced and popularized arthroplasty in the United States.26,27 Lexer,21 in 1909, emphasized the value of autogenous tissue and confirmed the impression of Murphy27 that fat and fascia were the best substances for interposition arthroplasty. He reported that fascia remained viable and was replaced by fibrous and fibrocartilaginous tissue. The observation has not been subsequently confirmed, rather the joint appears to be comprised primarily of fibrous tissue.29

OUTCOMES

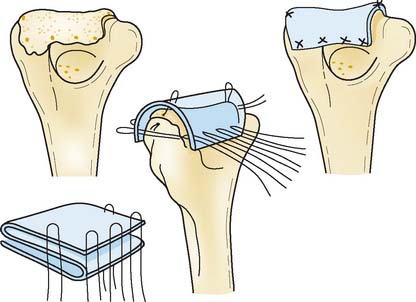

Autogenous or xenograft cutis has been used as an interposing membrane in resection arthroplasties (cutis arthroplasty) of various joints since 1913, and successful use in the elbow has been reported by several authors.9,16,24 Cutis is the thick dermal layer of skin that remains after the superficial epidermal layer has been removed. It is a tough, durable, elastic membrane, and it closely adheres to the cut surface of the distal humerus.

Fascia lata is easy to harvest and conforms readily to the bony surfaces, but the donor site leaves variable morbidity. Efforts to enhance its effect have been reported by Kita17 using chromicized fascia lata, the so-called J-K membrane.

In 1979, Shahriaree and colleagues33 reported that of 30 patients, 90% returned to their previous occupations after excisional arthroplasty with Gelfoam interposition. Smith and associates34 successfully used silicone sheets as interposition material in six patients with hemophilic arthropathy.

INDICATIONS

INTERPOSITION

Specific Indications

The basic indications for interposition arthroplasty are either incapacitating pain or loss of motion in an individual younger than 40 years of age with rheumatoid arthritis, and younger than 60 years of age with traumatic arthritis. Loss of motion may follow trauma, sepsis, burns, or degenerative or inflammatory arthritis. However, the most compelling indication for arthroplasty of the elbow is incapacitating functional loss. If the loss of motion and pain are postinfectious, careful evaluation must be done to ensure that the patient has been free of the infection, preferably for at least 1 year. The best indication for this procedure is post-traumatic, painful loss of motion not complicated by sepsis in an individual who does not require long-term heavy demand on the joint.25

CONTRAINDICATIONS

If recent sepsis has occurred, other than débridement, reconstruction should not be considered. If epiphyseal closure has not occurred, arthroplasty should be delayed until growth is complete. In the past, a major contradiction to interposition arthroplasty was inadequate bone stock. Grishin and colleagues,10 however, have reported using interposition arthroplasty in conjunction with reconstructive bone grafts for marked osseous deficiency.

We have found gross instability, deformity, and marked pain, especially at rest, are all associated with poorer outcomes.8,20,25 The patient with a grossly unstable elbow from rheumatoid or post-traumatic arthritis cannot be adequately stabilized by an interposition procedure. Congenital ankylosis of the elbow joint that lacks the necessary ligamentous support may be treated with interposition and ligamentous reconstruction. However, the absence of flexion motor power is an absolute contraindication to this procedure. The need to use the upper extremity in ambulation or for transfer from bed to chair is a relative contraindication because excessive loading of the elbow destabilizes the joint.

PREFERRED TISSUE

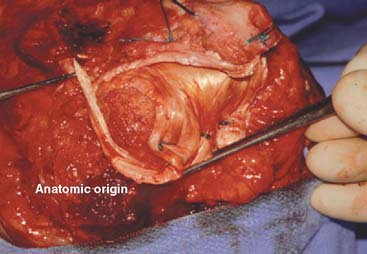

Autogenous skin and fascia and achilles tendon allografts have all been used by the senior author. The cutis is very durable and thick, rapidly adheres to the bone, and has generally been successful.4,7,9 The harvest techniques are attractive in those patients in whom primary closure may be carried out. Cutis tissue without the epidermis is somewhat more difficult to harvest. Fascia is also commonly used because it is readily available from the thigh and can be overlapped to ensure adequate bulk.18,25 Recently other processed tissues such as AlloDerm (LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ) are being investigated for this purpose.12 At present, we prefer the achilles tendon allograft because it is readily available. The following anatomic features are required for success of the procedure: absence of donor site morbidity, large size and thickness, sufficient material for ligament reconstruction if necessary, and presence of calcaneus if osseous graft is required.

PREFERRED TECHNIQUE—ACHILLES TENDON ALLOGRAFT

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

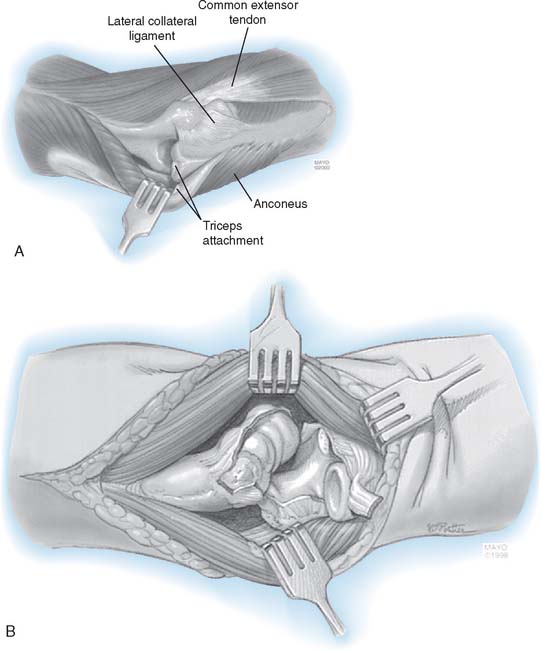

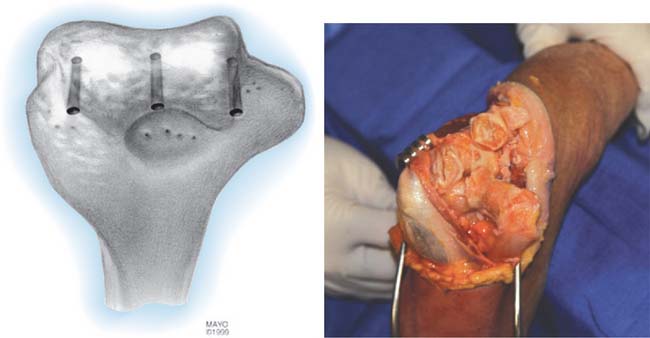

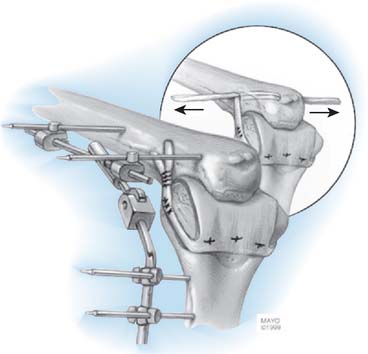

The patient is positioned supine with a pneumatic tourniquet in place. A posterior incision is preferred, although a pre-existing incision is reopened if consistent with the needed deep exposure. In all instances, the ulnar nerve is identified, mobilized, and protected throughout the case. The nerve is transposed subcutaneously if it is found to subluxate at the completion of the surgery. Kocher’s interval is developed between the anconeus and extensor carpi ulnaris. The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) complex and the common extensor muscles are released from the lateral condyle of the humerus. Anterior and posterior capsulectomy is performed to obtain useful elbow motion (Fig. 69-2). The tip of the olecranon is removed if it is prominent. The triceps muscle is elevated from the lateral distal humerus, and the anconeus mobilized from its ulnar attachment. The lateral one half of the triceps attachment is released from the olecranon, and the extensor mechanism is inserted as the forearm is flexed and supinated. If the cartilage appears beyond salvage, then the decision is made to proceed with interposition arthroplasty. The ulnar and humeral surfaces are prepared with a rongeur, burr, or semicircular saw to obtain a congruent articulation (Fig. 69-3). Care is taken to avoid resection of the subchondral bone, which may lead to excessive bony resorption, although the medial and lateral trochlear ridges are removed if necessary to obtain a smooth articulation. Sufficient bone is resected from the ulnar and humeral articular surfaces to accommodate at least 2 to 3 mm of joint space laxity even after insertion of the tendon to avoid “overstuffing” the joint.

Graft Application and Ligament Reconstruction

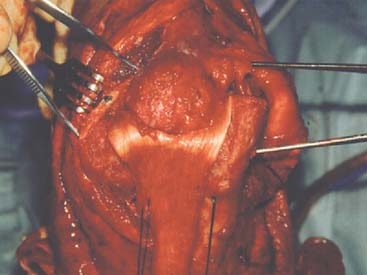

A fresh-frozen Achilles tendon allograft is our current preference (Fig. 69-4). Three or four drill holes are made across the distal humerus (see Fig. 69-3). Using a horizontal mattress stitch, the graft is sutured to the distal humerus through the drill holes (Fig. 69-5). The ulnohumeral joint is then reduced, and the integrity of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) is assessed. The smoothness of the articulation and elbow range of motion are determined. If adequate tissue is present, the lateral collateral ligament is repaired primarily. If the tissue is inadequate, reconstruction of the remaining portion of the ligament is carried out with the allograft tendon (Fig. 69-6). In cases in which both lateral and medial collateral ligaments are intraoperatively found to be deficient, a tunnel is drilled through the distal humerus, replicating the axis of rotation at the ulna. A second tunnel connects the sublime tubercle and the tubercle of the crista supinatorus. The distal strands of the allograft are threaded through the humeral tunnel and ulnar tunnels to create a “sling” simultaneously to reconstruct both the MCL and LCL (Fig. 69-7). The sling is hand-tensioned to maintain joint stability but still allow for smooth flexion and extension across the articulation. Following the reconstruction, the elbow is again taken through a range of articulated motion and tested for stability.

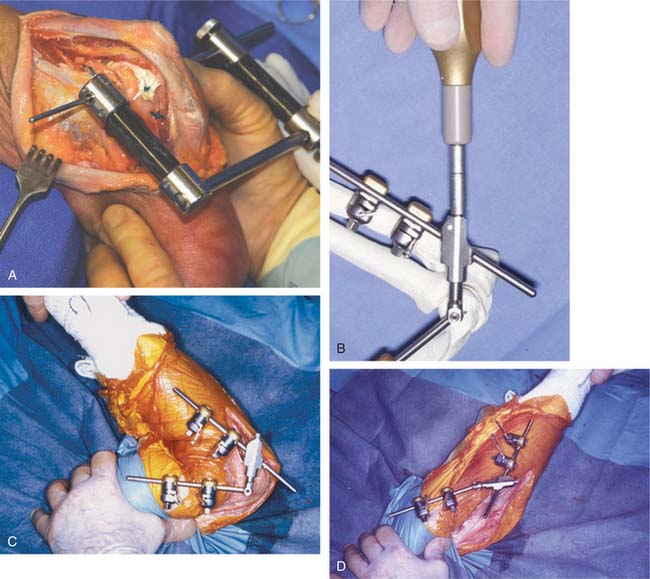

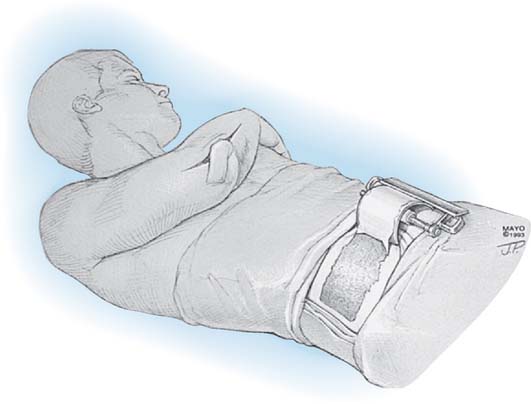

EXTERNAL FIXATION

Standard treatment today involves placement of an external fixator (DJD I or II Dynamic Elbow Joint Distractor, Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI). This device may be applied without damage to any collateral repair or reconstruction (Fig. 69-8). The fixator is intended to maintain stability and to distract or separate the joint, allowing for motion while protecting the interposition and the ligament reconstruction to allow for proper healing. In some instances, because of patient preferences, geographic distances rendering follow-up impractical, or surgeon’s intraoperative judgment, the fixator is not applied.

Aftercare

Patients are treated with continuous passive motion in the hospital for a mean of 2.3 days, typically with an axillary block for regional pain control. Today patients are routinely dismissed home on postoperative day two. At a mean of 30 to 35 days postoperatively, the patient returns for removal of the external fixator under anesthesia. The elbow is gently “examined” for stability and smoothness of the articulation, as well as being taken through a range of motion. No forceful maneuvers were employed, but the flexion and extension limits are stretched at this time. Mean range of motion obtained at the examination under anesthesia is about 115 degrees.1 Patients with persistent stiffness are prescribed static adjustable flexion and extension splints to be worn 23 hours per day for 3 weeks to maintain the range of motion obtained at the examination under anesthesia. Maintenance bracing is continued for 8 to 12 weeks. No dynamic splinting is used, and no patient is treated with formal physical therapy.

CUTIS ARTHROPLASTY

HARVEST AND APPLICATION

CUTIS HARVEST—FROIMSON

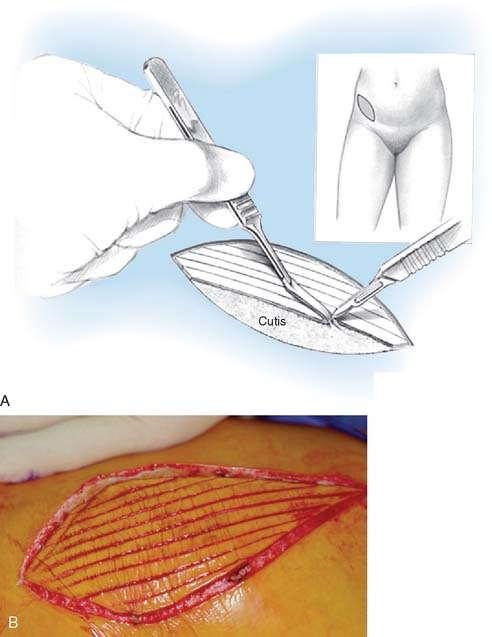

Using a hand-held or motorized dermatome, remove a thin split-thickness skin graft from the patient’s lower abdomen, leaving a standard split-thickness donor site with punctate bleeding. With a sharp knife, remove this deep dermal layer with minimal subcutaneous fat (Fig. 69-10). Secure hemostasis with electrocautery and use the split-thickness graft to cover the donor site.

LIMITED HARVEST—MORREY

An alternative method to harvest a limited graft has been developed. An elliptical pattern is placed in the bikini line (Fig. 69-11). Linear incisions just through the epidermis are made every 3 to 4 mm. The dermis is elevated leaving the cutis, which is sharply excised. The wound is closed primarily. This has the advantage of being a relatively quick procedure with a more pleasing scar at the donor site.

RESULTS

HISTORICAL

Early reports of fascial arthroplasty by Campbell,5,6 Henderson,13,14 and MacAusland and MacAusland23 showed that excellent or good pain relief and improvements in motion and function were obtained in about 75% of patients. In 1940, Speed and Smith35 noted that the best results could be obtained in patients between the ages of 18 and 40 years. In 1952, Knight and Van Zandt18 reported 56% good and 22% fair results in 45 patients an average of 14 years after fascial arthroplasty. Their best results were obtained in patients between the ages of 20 and 50 years. Most patients regained motion between 6 months and 6 years after surgery, and maximum strength was obtained at about 1 year. In 1967, Vainio37 reported that more than half of 131 patients undergoing fascial arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis were free of pain and had more than 90 degrees of flexion.

Subsequent reports have supported the value of fascial arthroplasty of the elbow in well-selected patients.9,16,24,36 Kita17 reported the use of a chromicized fascial interposition material in 31 patients in an attempt to reduce the inflammatory response initiated by fascia lata. At 19-year follow-up, half of his patients had excellent or good results and 20% had poor results. Uuspaa36 reported improved range of motion and decreased contractures after 51 cutis arthroplasties in 48 patients with rheumatoid arthritis; these patients ranged in age from 25 to 69 years. In a recent review of cutis arthroplasties in 14 patients ranging in age from 26 to 51 years, motion and medial-lateral stability were satisfactory in all.21 Although the technique is favored for rheumatoid arthritis in Europe, both rheumatoid and traumatic conditions are available to interposition arthroplasty if the proper indications are met (see Figs. 69-7, 69-8, and 69-12).

CURRENT EXPERIENCE

Rüther and colleagues31 recently reported the results of 61 procedures for rheumatoid arthritis and using dura mater, 17 of which were followed for less than 5 years, 52 between 5 and 10 years, and 12 for more than 10 years. Overall, 69% were satisfied and 70% had no or minimal activity restriction. Generally good results were reported in 14 with rheumatoid arthritis and followed 12 years after autogenous triceps fascial interposition.24 Ljung and associates22 described the results of 35 procedures using bovine cutis interposition and followed a mean of 6 years. Although 21 of 28 (75%) were pain free, functional limitation, especially instability, prompted the authors to recommend elbow replacement as the treatment of choice.

MAYO EXPERIENCE

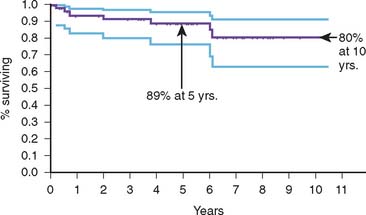

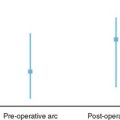

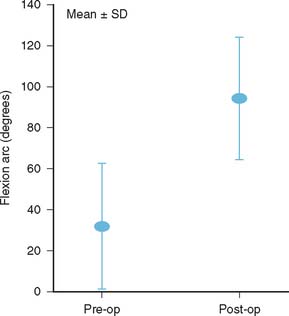

The initial experience was focused on a group of 60 patients with stiffness as the primary diagnosis.25 The concept of an aggressive soft tissue release, interposition with fascia lata and protection using an external fixator was introduced. With a follow-up of more than 5 years, more than 80% of patients were satisfied with the procedure. The arc of motion increased from a mean of 30 degrees to 90 degrees (Fig. 69-13).

FIGURE 69-13 Results after distraction interposition arthroplasty in patients with preoperative stiffness

In a subsequent study of 13 patients with traumatic arthritis but good motion (>80 degrees), Cheng and Morrey8 documented 75% satisfactory results using fascia lata, a mean of 5 years (range, 2 to 12 years) after surgery. It is of note that those without pre-existing instability revealed 80% satisfactory outcomes. Those with residual instability had a 50% unsatisfactory outcome (Fig. 69-14).

MAYO RECENT EXPERIENCE

Our experience has recently been updated by Larson et al.20 Between 1996 and 2003, 69 consecutive elbows underwent interposition arthroplasties, all with an achilles tendon allograft. A hinged external fixator was used postoperatively in two thirds of these patients. Overall, the patient population was young, averaging 39 years. About 25% were for inflammatory and 75% had post-traumatic arthritis. Details are available in 45 patients. The mean time to clinical follow-up was 6.0 years (range 2.9 to 10.5 years). Seven patients subsequently underwent revision surgery: two infection cases, two instability cases, one elbow arthrodesis for instability, and two elective total elbow arthroplasties.

In the thirty-eight patients with surviving allografts, the flexion-extension arc improved from a preoperative mean of 51 degrees to 97 degrees following surgery (P < 0.001, matched pairs analysis). Mean preoperative MEP score was 42 points, improving to a mean of 65 points postoperativeloy (P < 0.001), matched pairs analysis) (see Fig. 69-14). Only 30% demonstrated a satisfactory MEPS, however, subjectively 88% would repeat the procedure. Despite efforts to reconstruct collateral ligaments, preoperative instability on physical examination was associated with low MEPS (P = 0.03), and high DASH scores15 (P = 0.006, Fisher exact test) postoperatively when compared to patients with no preoperative instability. On the other hand, a well-balanced interposition procedure can last up to 20 years (Fig. 69-15).

We consider interposition arthroplasty a salvage procedure indicated for young active patients with severe inflammatory or post-traumatic arthritis, especially with limited elbow motion. Caution must be used in patients with primary surgical indication of instability or intense pain. Yet, it can be a reliable salvage in many patients (Fig. 69-16).

COMPLICATIONS

Bone resorption occasionally occurs at the distal humeral condyles. It may cause no difficulty, or it may contribute to instability, especially if resorption occurs more on one side than on the other. Subluxation and instability may occur from resorption or because of technical difficulties. Although the joint may function reasonably well in spite of medial or lateral subluxation, usually these patients do not do well, so if the tendency to subluxate is apparent at the time of the interposition arthroplasty, this is addressed by repairing or reconstructing the collateral ligaments and applying a distraction device.10 If this is not successful, then proceed to fusion or prosthetic replacement.

REVISION

Revision of failed interposition arthroplasty is usually due to pain, reankylosis, or instability. The result can deteriorate with time, especially in the active individual. Additional surgery may not be offered because frequently little more can be done to modify the symptoms or attain the expectations of the patient. If the precise cause of failure can be identified, revision is occasionally helpful.19 Larson and associates reported four of six successful re-interposition procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic. Typically, however, prosthetic replacement is the salvage procedure of choice and is readily performed (Fig. 69-17). Blaine et al3 reviewed our experience with 13 revisions of failed interposition to elbow replacement. With a mean surveillance of 9 years (2 to 16 years); 11 of 13 (85%) were classified as satisfactory. Hence, failed interposition can be successfully salvaged with prosthetic replacement.

1 Aragi, A., Celli, A., Adams, R. A., and Morrey, B. F.: The effect of examination under anesthesia on the stiff elbow following surgical release. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. (in press).

2 Baer W.S. Preliminary report of animal membrane in producing mobility in ankylosed joint. Am. J. Orthop. Surg. 1909;7:3.

3 Blaine T.A., Adams R., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty after interposition arthroplasty for elbow arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87A:286.

4 Brown J.E., McGraw W.H., Shaw D.T. Use of cutis as an interposing membrane in arthroplasty of the knee. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40A:1003.

5 Campbell W.C. Mobilization of joints with bony ankylosis: an analysis of 110 cases. J. A. M. A. 1924;93:976.

6 Campbell W.C. Operative Orthopedics. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Co., 1939.

7 Cannaday J.E. Some experiences in the use of the cutis graft in surgery: with case reports. South. Med. J. 1948;41:876.

8 Cheung S.L., Morrey B.F. Treatment of the mobile, painful arthritic elbow by distraction interposition arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2000;82B:233.

9 Froimson A.I., Silva J.E., Richey D. Cutis arthroplasty of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58A:863.

10 Grishin I.G., Goncharenko I.V., Kozhin N.P., et al. Restoration of the function of the cubital joint in extensive defects of bones and soft tissues using endoprosthesis and free skin grafts. Acta Chir. Plast. 1989;31:143.

11 Hass J. Functional arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1944;26:297.

12 Hausman M.R., Birnbaum P.S. Interposition elbow arthroplasty. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 2004;8:181.

13 Henderson M.S. What are the real results of arthroplasty? Am. J. Orthop. Surg. 1918;16:30.

14 Henderson M.S. Arthroplasty. Minn. Med. 1925;8:97.

15 Hudak P.L., Amadio P.C., Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: The DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand). The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996;29:602.

16 Hurri L., Pulkki T., Vainio K. Arthroplasty of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Chir. Scand. 1964;127:459.

17 Kita M. Arthroplasty of the elbow using J-K membrane. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1977;48:450.

18 Knight R.A., Van Zandt I.L. Arthroplasty of the elbow: an end-result study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1952;34A:610.

19 Larson, N., and Morrey, B. F.: Revision of failed inter-position arthroplasty by re-interposition procedure. (in press).

20 Larson, N., and Morrey, B. F.: Interposition arthroplasty as a salvage procedure of the elbow using an achilles tendon allograft. Accepted for publication, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. (in press), 2008.

21 Lexer E. Über Gelenktransplantationen. Arch. Klink. Chir. 1909;90:263.

22 Ljung P., Jonsson K., Larsson K., Rydholm U. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5((2)Part I):81.

23 MacAusland W.R., MacAusland A.R. The Mobilization of Ankylosed Joints by Arthroplasty. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1929.

24 Mills K., Rush J. Skin arthroplasty of the elbow. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1971;41:179.

25 Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:601.

26 Murphy J.B. Ankylosis: Arthroplasty-clinical and experimental. Trans. Am. Surg. Assoc. 1904;22:215.

27 Murphy J.B. Ankylosis: Arthroplasty, clinical and experimental. J. A. M. A.. 1905;44:1573. 1671, 1794

28 Payr E. Über die operative Mobilizierung ankylosierter Gelenke. Munch. Med. Wchnschr. 1910;37:1921.

29 Phemister D.B., Miller E.M. The method of new joint formation in arthroplasty. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1924;26:406.

30 Putti V. Arthroplasty. Am. J. Orthop. Surg. 1921;3:421.

31 Rüther W., Tillmann K., Backenhöhler G. Resection interposition arthroplasty of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Orthop. Rheum. 1992;5:31.

32 Schüller M. Chirungische mittheilungen über die chronish rheumatischen gelenkentzundungen. Arch. Klin. Chir. 1893;45:153.

33 Shahriaree H., Sajadi K., Silver C.M., Sheikholeslamzadeh S. Excisional arthroplasty of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:922.

34 Smith M.A., Savidge G.F., Fountain E.J. Interposition arthroplasty in the management of advanced haemophilic arthropathy of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65B:436.

35 Speed J.S., Smith H. Arthroplasty: a review of the past ten years. Int. Abst. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1940;70:224.

36 Uuspaa V. Anatomical interposition arthroplasty with dermal graft: a study of 51 elbow arthroplasties on 48 rheumatoid patients. Z. Rheumatol. 1987;46:132.

37 Vainio K. Arthroplasty of the elbow and hand in rheumatoid arthritis: a study of 131 operations. In: Chapchal G., editor. Synovectomy and Arthroplasty in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1967:66.