CHAPTER 8 Internal Snapping Hip Syndrome

A snapping hip, also referred to as coxa saltans, can be the result of external, internal, and intra-articular causes.1–3 In 1984, Schaberg and colleagues3 first classified the distinction between internal and external snapping hip. External snapping hip is the most common type, and is caused by the posterior iliotibial band or anterior border of the gluteus maximus slipping over the greater trochanter with hip flexion and extension. Intra-articular snapping hip can be caused by various pathologies within the hip joint, such as labral tears, loose bodies, articular cartilage flaps, displaced fracture fragments, or synovial chondromatosis.4,5 Recently, Byrd2 has suggested that the term snapping hip should only be used for extra-articular causes, because various intra-articular pathologies can be identified as causes of these symptoms.

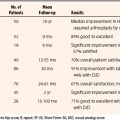

This chapter focuses on internal snapping hip, which refers to a symptom complex most commonly attributed to catching of the iliopsoas tendon when it moves laterally to medially as the hip moves from a flexed, abducted, and externally rotated position to extension and internal rotation (Fig. 8-1).1 In 1951, Nunziata and Blumenfeld6 first described internal snapping tendon in a case series of three patients. Although the exact cause of the snapping remains controversial, it has been most often hypothesized to originate from the movement of the tendon over the anterior femoral head, joint capsule of the hip, or iliopectineal eminence at the pelvic brim.2,7,8 Less commonly, the snapping may be caused by the iliopsoas tendon sliding over exostoses of the lesser trochanter.3 Alternate theories suggest that internal snapping may be caused by the iliopsoas tendon slipping over the iliopsoas bursa—the anterior inferior iliac spine—by stenosing tenosynovitis of the iliopsoas tendon at its insertion into the lesser trochanter, or by movement of the iliofemoral ligament over the anterior femoral head and joint capsule.9 In actuality, it is likely that various patients may have different sources for their snapping. Different surgical approaches have been suggested for treatment based on the specific structure believed to be responsible for the snapping,10 although it is basically a tight iliopsoas musculotendinous unit that most agree is part of the problem.

FIGURE 8-1 A & B (left to right), The proposed mechanism of snapping iliopsoas tendon. C, AP pelvic radiograph of a former soccer player with a traction spur of the lesser trochanter.

ANATOMY

The iliopsoas muscle, composed of the psoas major and iliacus muscles, is the strongest flexor of the thigh at the hip joint. It serves as an important postural muscle and prevents hyperextension of the hip joint when standing. The iliopsoas acts inferiorly to flex the trunk when rising from a supine to a sitting position. The psoas major muscle is innervated mainly by the ventral rami of L1 and L2. It has origins on the sides of the vertebral bodies, spinous processes, and intervertebral disks from T12 to L5. The iliacus muscle is mainly innervated by the femoral nerve and originates from the superior two thirds of the iliac fossa, ala of the sacrum, and anterior sacroiliac ligaments. The iliopsoas is unique in that it has both tendinous and direct muscular attachments; it first forms from the psoas muscle superior to the inguinal ligament. As the tendon runs inferiorly, it internally rotates and fans out to insert over the lesser trochanter. The iliacus tendon joins the posterior psoas tendon at the level of the pelvic brim and inserts into the body of the femur inferior to the lesser trochanter. When the hip is flexed, the iliopsoas tendon lies lateral to the center of the femoral head–anterior hip joint capsule and iliopectineal eminence. With hip extension and internal rotation, the tendon slides across the femoral head to lie medially (see Fig. 8-1).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Internal snapping hip has been estimated to exist incidentally in 5% of the population.2 Although the snapping phenomenon is frequently asymptomatic, in certain individuals it is accompanied by pain. Certain populations, such as ballet dancers and professional athletes, are more prone to painful snapping secondary to overuse.1,5,11,12 In one cross-sectional study, 91% of elite ballerinas reported experiencing snapping hip, with 80% having symptoms bilaterally but only 58% experiencing painful snapping. Clinical examination revealed the vast majority of these to be of the internal snapping type. The incidence of snapping hip has been noted to increase after total hip arthroplasty, often when a curved stem has been used. Usually, this can be classified as an external type of snapping hip, and it is thought to be related to catching of the posterior iliotibial band over the greater trochanter when the femoral component is placed too medially.1 With the advent of surface replacements, and the larger femoral head component, there appears to be an increased incidence of internal snapping hip following this procedure, as compared with a standard total hip arthroplasty, because the iliopsoas snaps over a more prominent acetabular component.

Internal snapping hip pain can manifest as groin pain that radiates to the anteromedial thigh and/or toward the knee. A dull ache after the snapping may be reported, and can last from minutes to hours.13 Rarely, internal snapping hip has been reported to cause pain in the lower back, flank, buttock, or sacroiliac joint.2,14 This type of pain is related to the posterior origins of the psoas (lumbar spine) and iliacus (posterior pelvis). The patient may report a history of painless snapping that has progressed to painful snapping. Internal snapping can occur unilaterally or bilaterally, and patients may or may not report a history of trauma. For internal or external snapping hip, the reported history of trauma is often minor and/or remote, whereas an acute history of significant trauma is often associated with intra-articular pathology. With intra-articular causes for snapping, patients more often report an intermittent clicking rather than a snapping sensation.

On physical examination, internal snapping hip is characterized by a painful and often audible clunk as the patient’s hip actively or passively moves from flexion, abduction, and external rotation to an extended, adducted, internally rotated position. Additional evidence to support the diagnosis of internal snapping hip can be gleaned if snapping is preceded by anterior pressure applied over the hip joint can.1,2

During the physical examination, it is critical to assess the patient for other causes of hip pain, including intra-articular causes. The Thomas test should be done to evaluate the patient for a flexion contracture of the iliopsoas or rectus femoris muscles. Patients may exhibit weak external rotation of the hip when it is in flexion and/or weak flexion of the hip while seated. Patients with internal snapping hip may also demonstrate an antalgic gait, most often externally rotated and abducted.5 The patient may also have pain and/or weakness with a resisted straight leg raise with the hip flexed at 15 degrees.

IMAGING

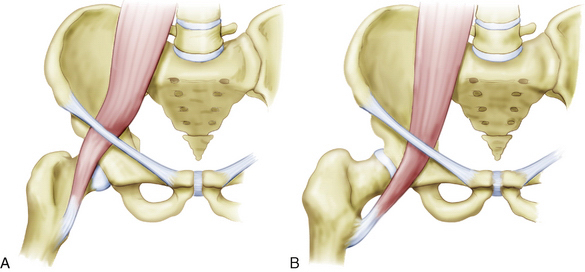

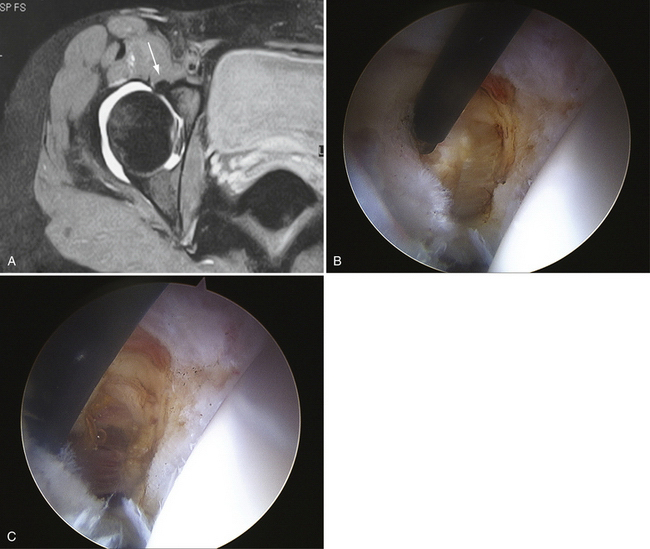

Plain radiographs and MRI scans are most commonly normal in patients with internal snapping hip, but they can be useful in ruling out other pathology. In patients in whom the snapping is secondary to lesser trochanter exostoses, synovial osteochondromatosis, or intra-articular loose bodies, there may be characteristic findings on plain films (see Fig. 8-1C). MRI can yield indirect evidence by demonstrating inflammation and/or swelling of the iliopsoas bursa (iliopsoas bursitis; Fig. 8-2A), or iliopsoas tendinopathy (see Fig. 8-2B). MRI is also important to rule out intra-articular causes for snapping hip, such as loose bodies and labral tears.

FIGURE 8-2 Axial cut MRI scans. A, Iliopsoas bursitis. Iliopsoas bursitis can accompany snapping hip. B, Professional tennis player with iliopsoas tendinitis. The arrow is pointing to the iliopsoas tendon, with the edema seen about the tendon.

Iliopsoas bursography can be a used to visualize the iliopsoas tendon catching in conjunction with the patient’s snapping.3,9,15 Diagnosis of internal snapping hip can be aided by a concomitant injection of bupivacaine (Marcaine), which may provide temporarily relief of the patient’s symptoms. Drawbacks to the use of iliopsoas bursography include difficulties associated with reproducing the snapping with the patient lying down constrained by the fluoroscopic imager located above the hip.2

The limitations of iliopsoas bursography can be overcome through the use of dynamic ultrasound to demonstrate the catching of the iliopsoas tendon.16 This technique allows for a greater range of motion at the hip to reproduce the snapping sensation. Other evidence in support of the diagnosis of internal snapping hip includes thickening of the iliopsoas tendon and peritendinous fluid collections. A diagnostic injection of bupivacaine can also be used with dynamic ultrasound to check for alleviation of symptoms. Disadvantages of dynamic ultrasound include the fact that results are technician-dependant, and its success also requires a high-resolution ultrasound machine.2

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Conservative Management

In most cases, internal snapping hips are asymptomatic and hence require no treatment other than reassurance. Patients should be counseled that painless internal snapping is a normal variant, and is not a sign of current or future pathology. For painful internal snapping hips, the first step is activity modification to avoid the movements that cause pain. Additionally, physical therapy, focusing on stretching and gentle strengthening of the hip flexors and abductors, and core stabilization may prove beneficial to some patients.1,14,17 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used to decrease pain and inflammation. The vast majority of symptomatic patients are successfully treated with conservative management. However, it can take several weeks before symptoms begin to improve, and several months to 1 year before pain resolves and normal function is regained. For athletes, the goal of treatment is to be pain-free prior to returning to sports. Corticosteroid injections into the iliopsoas bursa can also be used as an adjunct for patients who do not respond to the measures described.

Surgical Management

Open Techniques

In 1990, Jacobsen and Allen8 published their landmark study using an open technique that involved surgical lengthening of the iliopsoas tendon via release of its posteromedial tendinous portion (Z-plasty), leaving the anterior muscle belly intact. They used a transverse inguinal incision and anterior release, based on the idea that the iliopsoas tendon is catching over the anterior femoral head and joint capsule. They performed three to four partial tenotomies beginning 1 cm proximal to the lesser trochanter, with cuts every 2 cm proximally up to the level of the femoral head, where a complete release was done at the musculotendinous junction. Twenty hips were operated on in 18 patients, and the average follow-up was 25 months. Of these hips, 70% exhibited complete resolution of snapping, and 25% had partial resolution (with decreased frequency and less pain). Overall, patients subjectively felt improvement of their symptoms in 85% of hips. Postoperative complications of this study included a 50% incidence of decreased anterolateral thigh sensation, and a 15% incidence of weakness of hip flexion. Of these cases, 10% required reoperation for persistent painful snapping.

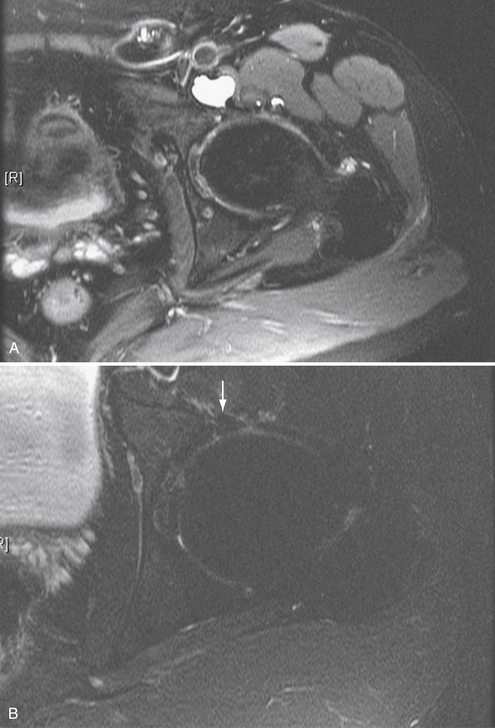

The results for this study were included in the retrospective 20-year consecutive review published in 2004 by Hoskins and associates18 (Table 8-1). Using the same fractional lengthening technique, data on a total of 92 hips in 80 patients were reported. The average postoperative follow-up was 6 months in their clinic and 5.4 years via telephone. Even though there was an overall complication rate of 43%, 89% of patients were satisfied with the procedure. In 22% of hips, snapping recurred after surgery, 9% of patients had decreased anterolateral thigh sensation, and 3% of patients experienced hip flexor weakness. Additional complications included one superficial infection, one hematoma, and one reoperation because of formation of a painful bursa over the lesser trochanter. Repeat tenotomies for recurring snapping resulted in heterotopic ossification in one hip and a femoral nerve palsy in another.

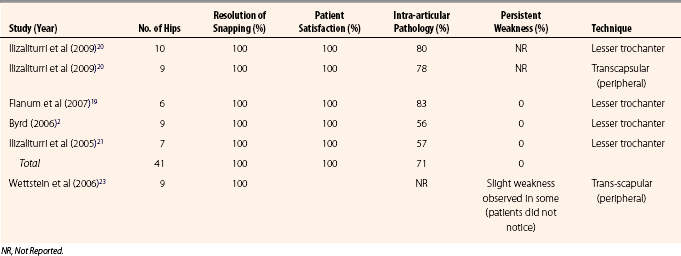

TABLE 8-1 Results of Surgery for Persistent Painful Snapping of the Hip Caused by the Iliopsoas Tendon in Athletes*

Taylor and Clarke13 have reported a technique for releasing the iliopsoas tendon at the lesser trochanter using a limited (5-cm) medial incision. The iliopsoas tendon was sectioned in the interval between the pectineus and adductor brevis. The authors hypothesized that this approach would avoid the possibility for lateral femoral cutaneous nerve injury and would provide better cosmesis. They performed their iliopsoas release 16 hips in 14 patients, with an average 17-month follow-up. All patients reported improvement in their symptoms; 57% reported complete resolution of snapping and 36% reported partial resolution of snapping. However, 14% of patients experienced postoperative weakness of hip flexion beyond 90 degrees, which was most pronounced when standing (see Table 8-1).

Dobbs and coworkers10 have published a case series that involved fractional lengthening (Z-plasty) of the iliopsoas tendon over the iliopectineal eminence in 11 hips of nine children. The investigators performed a fractional lengthening of the tendon at the musculotendinous junction in an attempt to avoid the weakness of hip flexion that occurred in Jacobsen and Taylor and colleagues’ studies.8,13,18 They used a modified iliofemoral approach with a large 5- to 7- cm incision to allow for proper visualization and complete release of the iliopsoas tendon. The approach was meant to protect the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which lies medial to their plane of dissection. After an average follow-up of 4 years, all patients were satisfied with the procedure. No patients exhibited any weakness of hip flexion, and 22% of patients experienced a transient decrease of sensation in the anterolateral thigh (proposed to be caused by traction on the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve). The authors advocated immense care to distinguish the iliopsoas tendon from the nearby femoral nerve properly. In their technique, the use of paralytics was avoided and the tendon was stimulated with very low-level electrocautery prior to lengthening to confirm that no nerve fibers were associated with it. Also of note, all 9 of the children in this study had been referred with incorrect diagnoses, even though each child reliably demonstrated the palpable anterior and medial snapping over their hip that is pathognomonic for internal snapping hip (see Table 8-1).

In 2002, Gruen and associates7 reported an open surgical technique that involved a true ilioinguinal approach and fractional lengthening (Z-plasty) of the iliopsoas tendon within the psoas muscle belly above the pelvic brim. Their study involved 12 hips in 11 patients with an average of 3 years of follow-up. All patients reported complete resolution of snapping, but 18% of patients reported that their hip pain recurred and was unchanged by surgery. Of these patients, 83% were satisfied with the pain relief that they obtained from the procedure, but 45% of patients experienced subjective weakness in hip flexion (80% of these patients only experienced weakness beyond 90 degrees of flexion). Investigators were unable to identify any weakness based on physical examination. One patient in the study underwent multiple reoperations, none of which were successful in relieving the pain (see Table 8-1).

Most complications with open iliopsoas releases may be related to one of several factors: (1) the approach used for the release can cause sensory deficits; (2) inadvertent sectioning of muscle in addition to the tendon can cause weakness of hip flexion; or (3) open releases are unable to address intra-articular pathology, which can lead to failure of the procedure and recurrence of painful snapping. As will be discussed, arthroscopic methods to release the iliopsoas tendon can overcome each of these issues.

Arthroscopic Techniques

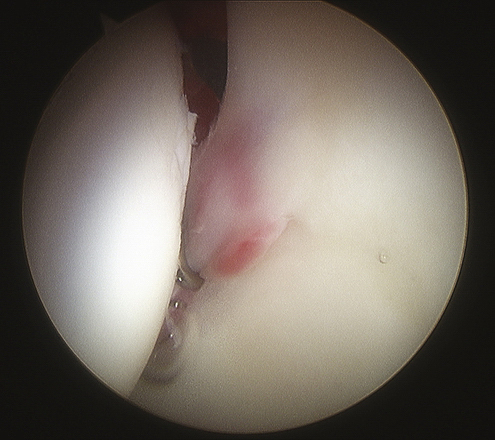

As a result of these limitations and complications of open management of internal snapping hip, arthroscopic approaches have evolved. The minimal incisions used for arthroscopic portals greatly decrease the chance for nerve injury. Arthroscopic visualization of the iliopsoas tendon allows for precise and complete release of the tendon, with very little damage to the muscle belly. Generally, the arthroscopic approach to the iliopsoas tendon comes directly on the tendon, so that direct sectioning of the tendon can be accomplished without cutting the muscle. This allows maintenance of iliopsoas function. Furthermore, the neurovascular structures at risk generally are on the opposite side of the musculotendinous unit, protected from the arthroscopic instruments by the iliopsoas muscle. Finally, during an arthroscopic iliopsoas release, diagnostic hip arthroscopy of the central and peripheral hip compartments is done to identify and address any intra-articular pathology (Fig. 8-3). Early results with arthroscopic release techniques have demonstrated that associated intra-articular injuries are present between 56% and 83% of the time.2,19,20

Innovations in hip arthroscopy techniques have led to the development of three different arthroscopic approaches to release the iliopsoas tendon. The procedure can be done extra-articularly within the psoas bursa at the level of the lesser trochanter, or it can be done via a trans-scapular release through either the peripheral or central compartments of the hip joint.2,20–23

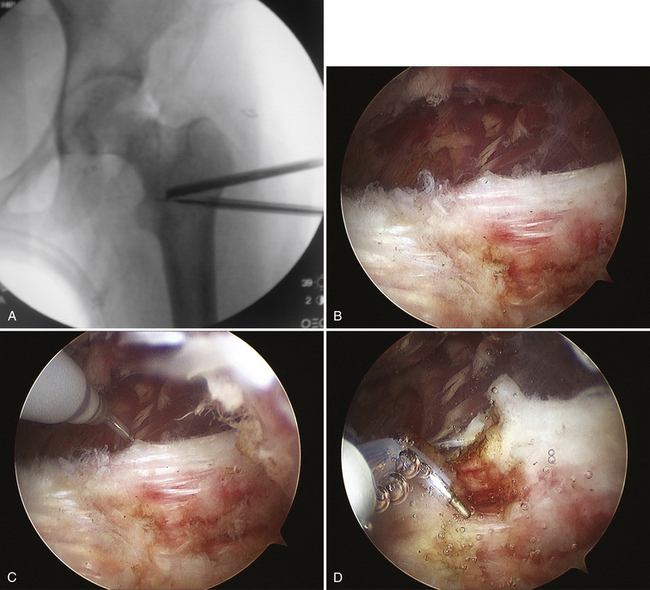

Releasing the iliopsoas tendon from its attachment at the lesser trochanter can be done using two accessory portals in addition to the standard hip arthroscopy portals (anterolateral, posterolateral, and anterior).2,21 On completion of hip arthroscopy on a fracture table, the instruments are removed and the traction is released. The lower extremity is placed into external rotation and the hip is flexed 15 to 20 degrees. The first accessory portal, the distal anterolateral portal, is made 2 to 3 cm distal and slightly anterior to the anterolateral portal at the level of the lesser trochanter using fluoroscopic guidance. A second accessory portal, the iliopsoas portal, is then placed 3 to 4 cm inferior to the distal anterolateral portal (Fig. 8-4A). These two portals are used for visualization of the iliopsoas tendon through the iliopsoas bursa and for instrumentation. The tendon usually appears as a bright white structure located behind the synovial tissue. To see the tendon better, a shaver can be introduced to clear adhesions and excess synovium within the bursa (see Fig. 8-4B). Once the tendon is clearly identified, it is transected directly adjacent to its insertion on the greater trochanter using an electrocautery or radiofrequency device, without incising any muscle (see Fig. 8-4C). If the tendon is transected more proximally, the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries may be endangered, because they wrap around the tendon 2 to 3 cm proximal to its insertion.19 Patients should be counseled prior to surgery to expect significant weakness of their hip flexors for 2 to 4 weeks after this release. Active strengthening of hip flexors should not begin until 6 weeks postoperatively (see Fig. 8-3).20 Postoperatively, patients are allowed to bear weight as tolerated, using crutches, until their gait is normal. There are some anecdotal reports of heterotopic ossification with this approach, although the senior author (MRS) has not seen this in his experience. Nonetheless, consideration should be given to heterotopic bone prophylaxis post operatively.

FIGURE 8-4 Release of the iliopsoas tendon at the level of the lesser trochanter. A, Fluoroscopic view of the arthroscopic camera and electrocautery at the level of the lesser trochanter. B, Arthroscopic view of the iliopsoas tendon at the level of the lesser trochanter. C, Electrocautery at the tendon. D, Tendon being cut at the level of the lesser trochanter. E, Schematic representation of the iliopsoas tendon being cut arthroscopically at the lesser trochanter.

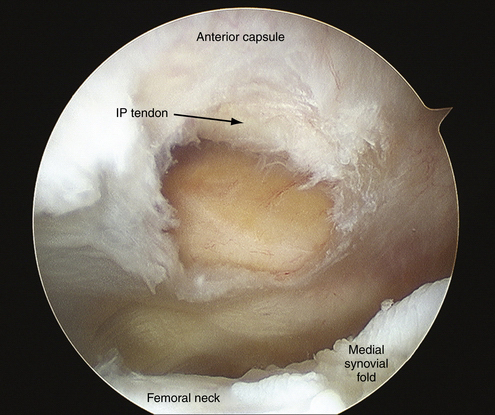

Wettstein and colleagues23 have described a technique to perform an iliopsoas tenotomy via a trans-scapular approach from the peripheral compartment of the hip. This technique does not require any additional portals beyond the standard hip arthroscopy portals. Following arthroscopy of the central compartment of the hip, instruments are removed, traction is released, and the hip is placed into 30 to 35 degrees of flexion, 5 to 10 degrees of abduction, and external rotation. The anterolateral and anterior portals to the peripheral compartment are then created. An arthroscope is inserted into the proximal anterolateral portal and used to identify the medial synovial fold, which is a critical landmark for this procedure. The medial synovial fold attaches distally to the lesser trochanter and bridges the anteromedial portion of the femoral head and articular joint capsule. At the level of the zona orbicularis, the medial synovial fold runs medially to the level of the iliopsoas, which is superficial to the capsule. Turning the arthroscope anteriorly, a 2-cm transverse capsulotomy is made medial to the medial synovial fold and proximal to the zona orbicularis. Here, the iliacus muscle protects the femoral neurovascular bundle and the iliopsoas tendon can be completely released (Fig. 8-5).

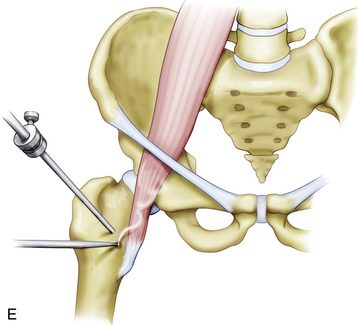

From the central compartment of the hip, the iliopsoas tendon is immediately medial to a thin veil of capsular tissue anterior to the joint (Fig. 8-6A). Identification of the iliopsoas tendon can be facilitated by using a probe to palpate the tendon. In cases of internal snapping hip, it is not unusual to have inflammation along the capsule adjacent to the psoas muscle and tearing or bruising of the adjacent labrum (see Fig. 8-3). Access to the tendon is made from a 1-cm capsulotomy adjacent to the anterior portal (see Fig. 8-6B). Once the tendon is identified, it is transected, leaving the overlying muscle fibers intact. When performing the iliopsoas tendon release from the central compartment, care must be taken to avoid injuring the femoral nerve that runs directly anteriorly to the iliopsoas at this level.22

FIGURE 8-6 A, Axial cut MRI scan demonstrating the relationship of the iliopsoas tendon to the anterior edge of the acetabulum at the level of the joint. The tendon is adjacent to the capsule. B, Iliopsoas tendon after a capsulotomy is made at the anterior capsule in the central compartment. The femoral head can be seen to the right. C, Iliopsoas muscle after the tendon has been cut.

In 2006, Byrd2 reported preliminary results using iliopsoas tendon release at the lesser trochanter in nine patients. With an average 20-month follow-up, 100% of patients experienced complete resolution of snapping and were satisfied with the procedure. None of the patients exhibited weakness or any other complications. Of the patients, 56% were found to have concomitant intra-articular pathology that was addressed during surgery (Table 8-2).

Using the same arthroscopic technique of release of the iliopsoas tendon at the lesser trochanter, Ilizaliturri and associates21 have demonstrated similar results in a study on seven hips in six patients. Followed for an average of 21 months, 100% of patients experienced resolution of snapping and pain and all patients were satisfied with the procedure. In this study, all patients exhibited significant weakness of hip flexion, but it was completely improved by 8 weeks. No other complications were observed. Of these patients, 57% were found to have intra-articular pathology at the time of surgery (see Table 8-2).

Flanum and coworkers19 have published a case series of six patients with unilateral internal snapping hip confirmed by ultrasound-guided injection of the psoas bursa. All patients were treated with arthroscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon at the lesser trochanter. After 12 months of follow-up, 100% of patients had complete alleviation of painful snapping of their hips; 33% of patients reported occasional slight pain in their hips. Weakness of hip flexors was resolved in all patients by 8 weeks. Intra-articular pathology during the operation was found in 83% of patients. The mean modified Harris hip score was 58.3 preoperatively and 62.3, 84.5, 90.3, and 95.7 at 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 months respectively (see Table 8-2).

Of these 6 patients, 3 were included in a case series by Anderson and Keene4 that investigated return to sport after arthroscopic iliopsoas tendon release in 15 athletes. Five subjects were classified as competitive athletes (2 college, 3 high school), and 10 were classified as recreational athletes. Of the 12 additional patients, 75% were found to have intra-articular pathology at the time of surgery. In this series, mean modified Harris hip scores were 41 and 44 points preoperatively for the competitive and recreational athletes, respectively. Postoperative scores were 87 and 63 at 6 weeks and 94 and 98 at 6 months. All 15 athletes had returned to participation in sports by an average of 9 months postoperatively. With an average follow-up of 17 months, all patients experienced complete alleviation of painful snapping and no recurrence. No patients experienced any weakness, decreased range of motion, sensory deficits, or other complications secondary to the surgery. There were 2 patients in these series who experienced greater trochanteric bursitis 6 weeks postoperatively because of an altered gait pattern, probably as a result of decreased power of hip flexion. This pain resolved after the patients were placed back on crutches and gradually weaned off during the subsequent 2 weeks.

In their 2006 paper detailing their technique for trans-scapular iliopsoas release from the peripheral hip compartment, Wettstein and colleagues reported preliminary data from nine patients. After a mean follow-up of 9 months, all patients had resolution of snapping, and no complications were reported. The incidence of intra-articular pathology was not reported. Of note, the authors mentioned that they observed “a permanent slight decrease in strength for deep hip flexion in some patients, with no subjective feeling of it.”23 Although no further data were given, this issue needs to be addressed in future studies using this technique.

Recently, Ilizaliturri and colleagues20 published the results of a randomized clinical trial that compared the results from endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon at the lesser trochanter (group 1, 10 patients) and trans-scapular arthroscopic psoas release from the peripheral compartment (group 2, 9 patients). Their results demonstrated no significant clinical differences in the results between the two groups; both techniques were found to be equally effective and reproducible. Snapping and pain were 100% resolved in both groups, and there were no complications in either group. Coexisting intra-articular pathology was found in 80% of patients in group 1 and 78% of patients in group 2. Postoperative Western Ontario and McMaster (WOMAC) University osteoarthritis index scores at a minimum 1-year follow-up were not significantly different between the two groups, and both groups exhibited a statistically significant improvement from preoperative WOMAC scores. All patients in this study were given 400 mg of celecoxib daily for 21 days following surgery as prophylaxis for heterotopic ossification (HO).

To our knowledge, there have been two reports of HO occurring after surgical treatment for internal snapping hip; both of these occurred after open fractional lengthening of the iliopsoas tendon was performed through a transverse inguinal approach.18,24 However, as noted, there has been anecdotal discussion of HO following arthroscopic iliopsoas release at the lesser trochanter.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

1. Allen WC, Cope R. Coxa saltans: the snapping hip revisited. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:303-308.

2. Byrd JW. Evaluation and management of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:347-355.

3. Schaberg JE, Harper MC, Allen WC. The snapping hip syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:361-365.

4. Anderson SA, Keene JS. Results of arthroscopic iliopsoas tendon release in competitive and recreational athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:2263-2371.

5. Wahl CJ, Warren RF, Adler RS, et al. Internal coxa saltans (snapping hip) as a result of overtraining: a report of 3 cases in professional athletes with a review of causes and the role of ultrasound in early diagnosis and management. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1302-1309.

6. Nunziata A, Blumenfeld I. Cadera a resorte: A proposito de una variedad. Prensa Med Argent. 1951;38:1997-2001.

7. Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of the internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:607-613.

8. Jacobson T, Allen CW. Surgical correction of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:470-474.

9. Harper MC, Schaberg JE, Allen WC. Primary iliopsoas bursography in the diagnosis of disorders of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;221:238-241.

10. Dobbs MB, Gordon JE, Luhmann SJ, et al. Surgical correction of the snapping iliopsoas tendon in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:420-424.

11. Reid DC. Prevention of hip and knee injuries in ballet dancers. Sports Med. 1988;6:295-307.

12. Winston P, Awan R, Cassidy JD, Bleakney RK. Self-reported snapping hip syndrome in elite ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:118-126.

13. Taylor GR, Clarke NM. Surgical release of the “snapping iliopsoas tendon.”. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:881-883.

14. Little TL, Mansoor J. Low back pain associated with internal snapping hip syndrome in a competitive cyclist. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:308-309.

15. Vaccaro JP, Sauser DD, Beals RK. Iliopsoas bursa imaging: efficacy in depicting abnormal iliopsoas tendon motion in patients with internal snapping hip syndrome. Radiology. 1995;197:853-856.

16. Pelsser V, Cardinal E, Hobden R, et al. Extraarticular snapping hip: sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:67-73.

17. Keskula DR, Lott J, Duncan JB. Snapping iliopsoas tendon in a recreational athlete: a case report. J Athletic Training. 1999;34:382-385.

18. Hoskins JS, Burd TA, Allen WC. Surgical correction of internal coxa saltans: a 20-year consecutive study. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:998-1001.

19. Flanum ME, Keene JS, Blankenbaker DG, DeSmet AA. Arthroscopic treatment of the painful “internal” snapping hip. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:770-779.

20. Ilizaliturri VMJr, Chaidez PA, Villegas P, et al. Prospective Randomized study of 2 different techniques for endoscopic iliopsoas tendon release in the treatment of internal snapping hip syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:159-163.

21. Ilizaliturri VMJr, Villalobos FEJr, Chaidez PA, et al. Internal snapping hip syndrome: Treatment by endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1375-1380.

22. Kelly BT, Williams RJ3rd, Philippon MJ. Hip arthroscopy: current indications, treatment options, and management issues. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:1020-1037.

23. Wettstein M, Jung J, Dienst M. Arthroscopic psoas tenotomy. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:907.

24. McCulloch PC, Bush-Joseph CA. Massive heterotopic ossification complicating iliopsoas tendon lengthening. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:2022-2025.