CHAPTER 12 Internal Brow Lift: Browplasty and Browpexy

An internal brow lift offers the patient a method of raising the eyebrow without any additional incisions or scars; however, it is useful only for mild brow ptosis that is confined to the central and temporal aspect of the eyebrow. The technique does not lift the nasal brow, reduce excessive tissue above the nose, or treat overaction of the corrugator or procerus muscle. Nonetheless, I have been using this technique for several decades and find it invaluable in many cases.

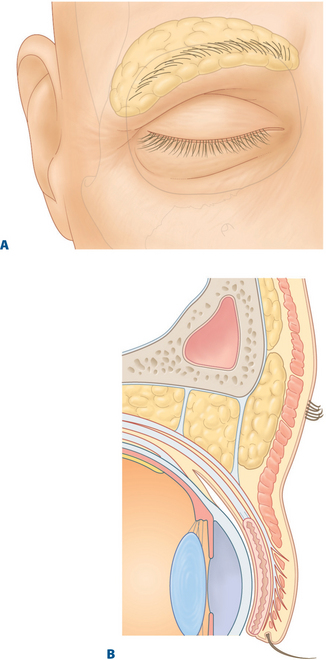

There are some patients who have a unilateral brow ptosis that leads to asymmetric upper eyelid creases and folds (Fig. 12-1). In these patients, the internal brow lift not only makes the brows more symmetrical but also helps symmetry of the upper eyelid creases and folds.

The internal brow lift (browpexy) and excision of excessive brow fat (browplasty) are important adjunctive procedures in selected blepharoplasty patients.1–3

Anatomic considerations

The eyebrow and its surrounding soft tissues represent a specialized anatomic region of the face and the superficial sliding muscle plane of the forehead. Cadaveric studies by Lemke and Stasior4 have helped to define the brow-eyelid anatomic unit and its importance in repair of brow ptosis and dermatochalasis.

A fat pad exists beneath the eyebrow, from which dense attachments secure the brow to the supraorbital ridge. This fat pad enhances eyebrow motility, especially laterally, where it is most pronounced (Fig. 12-2A). The brow fat pad often extends inferiorly into the suborbicularis fascia-preseptal plane in the upper eyelid and can be mistaken for orbital fat by the novice blepharoplasty surgeon (Fig. 12-2B).

Indications

Although the coronal and endoscopic forehead lift procedures provide the most pronounced correction of forehead and glabella laxity, these techniques may be more extensive than the patient or surgeon desires. It should be emphasized that the internal browpexy procedure does not replace conventional brow lifts and should not be done in patients with severe brow ptosis (see Chapter 6).

I have also found the internal brow approach to be useful in lowering an abnormally high eyebrow that occurs from fixation of the brow to periosteum from trauma.5 In these cases the brow is sutured to the level of the superior orbital rim.

Surgical technique

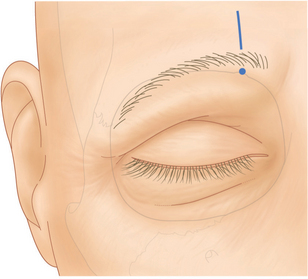

The amount of brow lift desired is determined while the patient is seated on the operating table. The site of the blepharoplasty is marked in the upper lid crease, and the supraorbital notch is palpated and marked to localize the supraorbital nerve and vessels (Fig. 12-3). The patient can then be reclined, and the upper eyelid and brow infiltrated with 2 percent lidocaine with epinephrine.

Browplasty

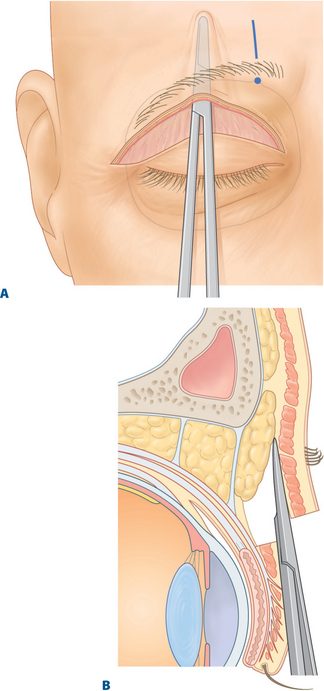

After the standard blepharoplasty excision of the skin and orbicularis muscle, the dissection is extended superiorly toward the brow in the submuscular plane in the postorbicularis fascia (Fig. 12-4A and B). Dissection should extend approximately 1–1.5 cm above the superior and lateral orbital rim. The brow fat pad can then be identified overlying the lateral orbital margin. As has been emphasized, excision of the fat pad should be confined to the lateral aspect of the brow to avoid injury to the medial supraorbital neurovascular complex. Only partial sub-brow fat is removed as some fat should be retained over the orbital bone to avoid a depression of skin in this area.

Following identification and exposure of the brow fat pad, an elliptical section measuring 1–1.5 cm vertically and tapering nasally and temporally can be marked with methylene blue (Fig. 12-5A). The fat pad is then removed on bloc from the central third of the superior orbital margin and laterally as far as the frontozygomatic structure (Fig. 12-5B). The fat pad should be removed down to, but not including the periosteum but leaving a thin layer of fat over the periosteum. The periosteum and a superficial layer of fat should remain intact so that adhesions can be avoided in an area designed for motility. Also, some fullness in this area is aesthetically desirable. If brow fixation or elevation is not desired, the blepharoplasty can then be completed.

Browpexy

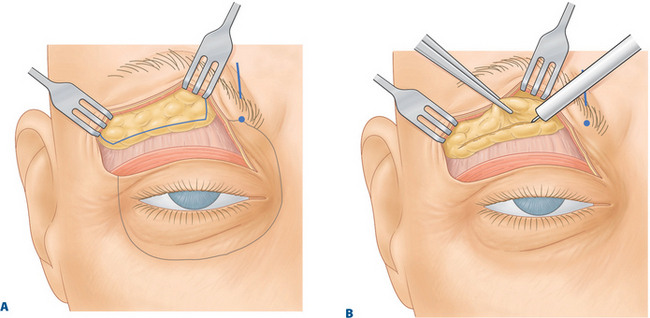

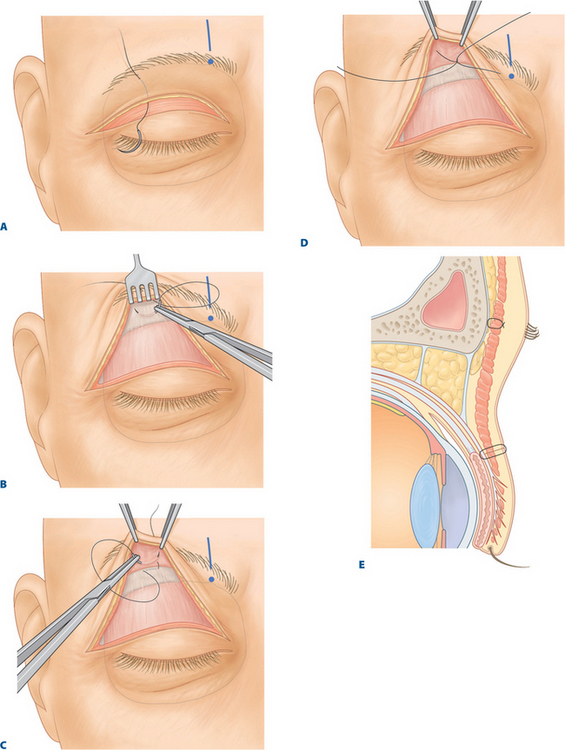

Fixation or plication of the brow to the supraorbital rim periosteum can provide elevation of the ptotic or lax brow. One to three 4-0 polypropylene (Prolene) sutures are passed transcutaneously from the lower edge of the brow hairs into the previously dissected sub-brow space approximately 1 cm apart (Fig. 12-6A). The transcutaneous introduction of the sutures allows the surgeon to mark the position of the brow hairs while working underneath the dissected flap.

Each suture is then passed through periosteum approximately 1–1.5 cm above the supraorbital rim (Fig. 12-6B). At this stage of the procedure, the height and curvature of the brow can be adjusted according to the patient’s gender. Placing the more central suture slightly higher allows the characteristic arch of the female brow to be restored or preserved.

The sutures are then passed again into the sub-brow muscular tissue at the level of the original transcutaneously passed marking suture (Fig. 12-6C). It is important to engage firm subcutaneous tissue so that the polypropylene browpexy sutures have the desired effect. The surgeon must, however, avoid suturing into the very superficial sub-brow tissues. This can lead to a dimpling of the skin as well as erosions of superficial tissues over the sutures and exposure of the sutures.

The original transcutaneous suture end is then pulled through the skin under the flap. The sutures are tied carefully over a 2–3 inch piece of 4-0 silk knot releasing suture in an attempt to avoid overtightening the 4-0 polypropylene loop (Fig. 12-6D). The patient is sat up on the operating table and the brow position is studied. If the brow is too high or low or if the arch is unsatisfactory, then the 4-0 silk suture is pulled to release the Prolene tie and the suture is replaced until the desired brow position is achieved. Ideally, these subcutaneous sutures should provide a mild brow-lifting effect and still allow the brow a good range of mobility (Fig. 12-6E).

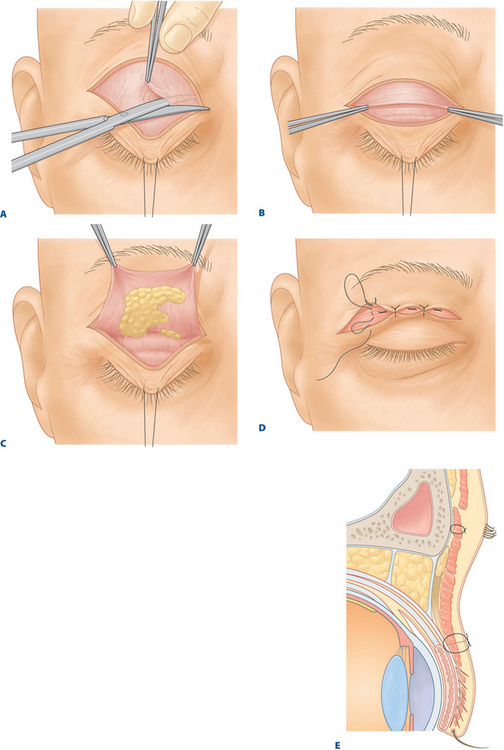

Once the brow is set in the proper position, the surgeon penetrates the orbital septum and suborbicularis fascia. This is achieved by pulling the upper lid downward with a 4-0 silk traction suture that has been placed through central skin, orbicularis and superficial tarsus. The orbital septum and suborbicularis fascia are picked up with toothed forceps and pulled upward and outward. The tented inferior aspect of the septum and suborbicularis fascia is penetrated with Westcott scissors until the subseptal space can be see (Fig. 12-7A). The area then is widened by spreading the scissors blades.

With the eyelid still kept in this position with traction suture and forceps, one blade of the Westcott scissors is used to penetrate the central opening in orbital septum-suborbicularis fascia and is slid across the temporal eyelid. Cutting with the Westcott scissors proceeds anteriorly, and the septum-suborbicularis fascia is cut at its inferior aspect (Fig. 12-7A).

The maneuver is repeated over the nasal half of the orbital septum-suborbicularis fascia. The maneuver creates a flap of septum-suborbicularis fascia that has an inferior edge close to the superior tarsal border (Figs 12-7B and C).

An eyelid crease is formed by attaching three 6-0 white polyester fiber (Mersilene) sutures from the orbicularis muscle of the lower skin flap to levator aponeurosis. Next, three 6-0 white polyglactin (Vicryl) sutures are sewn to connect skin to levator aponeurosis and to the inferior edge of the septum-suborbicularis fascia flap (Figs 12-7D and E). One of these sutures is placed centrally, and one is placed nasally and temporally. The skin is closed with a 6-0 black silk suture run continuously.

Complications

One complication of internal brow lifts is dimpling of the skin in the area of the sutures if they pass too close to the skin. Most of the time, this problem can be determined during the surgical procedure and replacement of the suture can avoid the complication. If dimpling is noted postoperatively, it will usually resolve in a few months, but if not, then massaging the area frequently resolves the problem.

Results

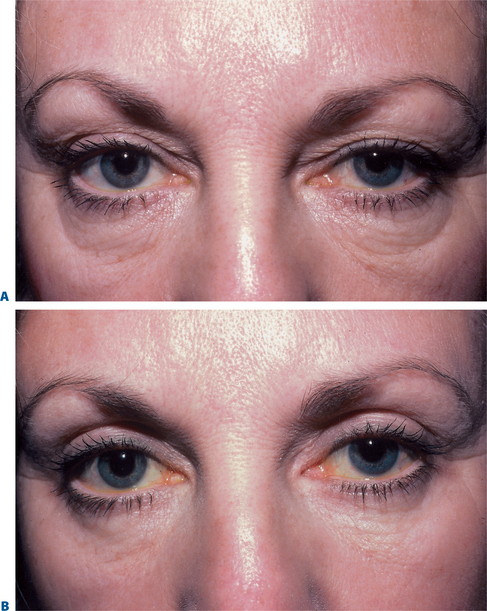

I have used the browplasty and/or browpexy procedures over the past two decades in more than 100 selected patients undergoing upper blepharoplasty and have had good results (Figs 12-8 and 12-9).

Figure 12-8 A, Preoperative photo of patient with fullness of temporal sub-brow due to thickened sub-brow fat.

B, Same patient after excision of sub-brow fat (browplasty).

1 McCord CD, Doxanas MT. Browplasty and browpexy. An adjunct to blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:248-254.

2 May JW, Pearon I, Zingarelli P. Retro-orbicularis oculus fat (ROOF) resection in aesthetic blepharoplasty: A 6-year study in 63 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:682-689.

3 Stasior OG, Lemke BN. The posterior eyebrow fixator. Adv Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;2:193-197.

4 Lemke BN, Stasior OG. The anatomy of eyebrow ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:981-986.

5 Putterman AM. Treatment of retracted eyebrow through eyelid approach. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:674-676.