11 Interdisciplinary Education and Training

Principles of Adult Education

These attributes lead to highly pragmatic learners who are likely to be motivated when the material is relevant. They are able to be critical about the value of what they learn. When adult learners feel respected by the teachers, they can actively test what they learn in the real world, integrating new learning into their professional roles1 (Box 11-1).

Principles of Interdisciplinary Education

The World Health Organization (WHO) says “Interaction is the important goal, to collaborate in providing preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and other health-related services”2 regarding interdisciplinary education. Other goals include “enhancing” or “improving” both collaboration and quality of care3 (Table 11-1).

| Institute of Medicine—IOM11 | Interprofessional Education Consortium—IPEC12 |

|---|---|

| Provide patient-centered care | Family-centered practice |

| Work in interdisciplinary teams Employ evidence-based practice Apply quality improvement Use informatics | Integrated services through collaboration and/or group process |

| Assessment and outcome | |

| Social policy issues | |

| Communication | |

| Leadership |

There is a mantra in palliative care circles that interdisciplinary teamwork and learning are beneficial. However, the supporting research and literature is limited, and where available, remains controversial. A review of the general and academic literature on interdisciplinary education identifies some of the salient qualities, benefits, and challenges4 (Table 11-2).

TABLE 11-2 Interdisciplinary Education: Benefits and Challenges

| Benefits | Challenges and/or disadvantages |

|---|---|

The Pedagogy of Pediatric Palliative Care

Unique dynamics of pediatric palliative care

Core Curriculum

Although communication is listed equally among the components below, enhanced communication with patients, families, and colleagues is a priority and an intrinsic part of all the topics. Pediatric residents wished for “aspects of communication” as 4/5 of their top choices for additional education.5 Core educational components include:

Team interdisciplinary education and training

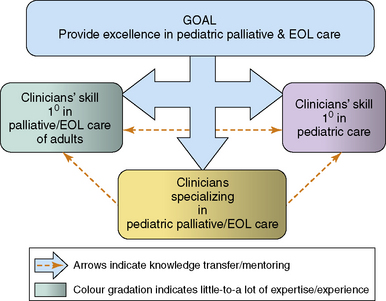

A dynamic mix of clinicians, from different disciplines and with varied skills, requires training in pediatric palliative care (Fig. 11-1).

Interdisciplinary groups provide an opportunity to share information from each individual and discipline’s perspective. Because each discipline has unique educational preparation, philosophy, and standard of practice, a common forum lends a richness and diversity to the group’s knowledge. Furthermore, it fosters respect and appreciation for each individual’s contribution. Research suggests that the earlier students from different disciplines are paired, the better their perceived understanding of roles.16 Medical student participants shared what they perceived as institutional support or the lack thereof in interprofessional interventions.17 Both within and outside the formal teaching session, the frequent and ongoing modeling of interdisciplinary practice must be considered in curricula implementation.18,19 The evaluation of these initiatives is also crucial because trainees’ perceptions of the importance of educational material is strongly linked to such data.20

Emerging research identifies the educational needs of the support staff on the pediatric palliative care team. A recent study pointed out that professional, educational, and emotional needs were notably unmet in this heterogeneous community of care providers. Although they had significant and direct contact with dying children and their families, none of them had received training in coping strategies and grief.21

Informal focus groups of trainees in pediatric palliative care rated respect of one another’s disciplines as the most important outcome of an interdisciplinary educational initiative.13 An integral component described by Health Canada is the development of mutual understanding for the contributions of various disciplines.18 In this emotionally difficult field, such respect may help prevent and reduce staff distress, communication obstacles, and conflict. Furthermore, the sharing of experiences and perceptions across disciplines leads to the recognition of universal reactions and emotions. An Australian interdisciplinary education palliative care model involved 537 participants, whose feedback requested more group sharing.22 Pediatric hematology-oncology and critical-care physicians noted that observing senior physicians in difficult conversations with families was the most helpful aspect of their palliative care training.14 It bodes well for interdisciplinary education that respondents also requested that team members from disciplines other than medicine be involved in teaching of communication skills.

Setting the stage for a level playing field within the group is essential within interdisiplinary education. For example, although nurses are often the most numerous of the participants, their input may be dismissed if there is a real or imagined power differential between them and the physicians present. On the other hand, the number of nurses may intimidate individuals from less well-represented disciplines. A study evaluating interdisciplinary workshops found that male participants and physicians tended to take over in role play and discussion formats.23

Strategies

Suggested questions for an interdisciplinary audience include:

Parents and families as teachers

The core of pediatric palliative care is the relationship between the clinical team and the family. The involvement of the child and family in ongoing professional development may enhance that relationship. Family members have described the importance of continuous care coordinated through the efforts of an interdisciplinary team.24 It is possible to train clinicians to be effective members of this team. Family members, including the child, can be interviewed or play roles in vignettes. Some programs have used innovative techniques such as developing scripts based on real situations with input from families. Actors then play the role of the patient or family with the clinicians acting as themselves.25 Clinicians may gain a deeper understanding of parents’ decision-making processes upon hearing their accounts firsthand.26 The teaching provided by families provides a unique perspective, and the team should be advised to heed carefully what they hear, and consider these messages in the evolution of their own practice.

The “Voice of the Child” as Teacher

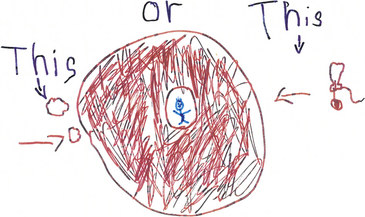

The following drawing and description by Mikaela, a ten-year-old girl with a brain tumor, provides an example of teaching from the child’s images and words, as well as valuable insight into the child’s understanding of illness, capacity, decision-making and autonomy (Fig. 11-2). Mikaela shows her picture about cancer-related treatment decisions, and says “I feel like I’m stuck in the middle of a doughnut”27not knowing which option to choose. As described by her psychologist, Mikaela drew tumor cells on one side and a lumbar puncture needle on the other.27

Fig. 11-2 This or this.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: Pediatric Palliative Care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9): 345-392, 2005.)

Mikaela describes her picture to her psychologist by saying: “What I mean by ‘I was stuck in a doughnut’ is that I had two choices and I didn’t want to take either of them. One of the choices was to get needles and pokes and all that stuff and make the tumor go away … even perhaps, it might have came back. My other choice was letting my tumor get bigger and bigger and I would just go away up to heaven. … My mom wanted me to get needles and pokes. But I felt like I just had too much. Too much for my body, too much for me. … so I kind of wanted to go up to heaven that time. … But then I thought about how much my whole entire family would miss me and so just then I was kind of like stuck in a doughnut.”27

Prompts for discussion include:

Can you share some of your thoughts after hearing from Mikaela?

Do you think Mikaela understands the implications of her illness?

Do you think Mikaela understands the decisions related to her illness?

What are your thoughts about capacity? Do you think Mikaela has capacity?

Do you think Mikaela is able to decide about the treatment of her illness?

What are your thoughts about patient autonomy when you hear Mikaela talk about her family?

Integration of the medical humanities

“We define the term ‘medical humanities’ broadly to include an interdisciplinary field of humanities (literature, philosophy, ethics, history, and religion), social science (anthropology, cultural studies, psychology, sociology), and the arts (literature, theater, film, and visual arts) and their application to medical education and practice. The humanities and arts provide insight into the human condition, suffering, personhood, our responsibility to each other, and offer a historical perspective on medical practice. Attention to literature and the arts helps to develop and nurture skills of observation, analysis, empathy, and self-reflection—skills that are essential for humane medical care. The social sciences help us to understand how bioscience and medicine take place within cultural and social contexts and how culture interacts with the individual experience of illness and the way medicine is practiced.”18

Family stories that are shared publically may be effectively incorporated as interdisciplinary teaching tools. For example, newspaper journalist Ian Brown chronicles his experience of parenting Walker, his 12-year-old son with a complex chronic illness,29 in The Boy in the Moon.

Evaluative tools

In addition to discipline-specific competency evaluation, researchers of pedagogy have some tools to evaluate interdisciplinary education. However, little is published relating to palliative care, and even less that is specific to pediatric palliative care. For example, although the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) is available, it has not yet been applied to palliative care-related education.30 However, some tools can be extrapolated and modified. For example, medical and social work students who received interdisciplinary education demonstrated a significantly better ability to lead family conferences in palliative care than the control group.31

The Pediatric Palliative Care Service was consulted when Riley was 41/2 months old (Fig. 11-3). He had been awaiting a neurologic consultation for hypotonia when he was admitted with pneumonia and severe respiratory compromise. He was diagnosed with Spinal Muscular Atrophy, a progressive, life-threatening, neurodegenerative illness. The following quotes are taken from a note written to members of the palliative care team, following Riley’s death at 14 months of age. Riley’s parents wrote: “We are so thankful for all the time you spent with us when Riley was diagnosed. Those hours you spent with us engaging us in productive, honest conversation were very positive for us. It helped us frame our hopes and wishes for Riley; how far we’d go with his care and his end of life care. Without our conversations I’m afraid we would have avoided thinking about those ‘hard’ things until we were in a critical, emotional time. I’m sure those decisions would have been much harder and not always thought through at those times.”

Fig. 11-3 Riley’s story elucidates the comprehensive care that a competent palliative care team can provide.

This provides a poignant description of how the palliative care team ensures:

1 Wlodkowski R.J. Enhancing adult motivation to learn. A comprehensive guide for teaching all adults. John Wiley and Sons Inc, 2008.

2 Learning together to work together for health. Report of a WHO study group on multiprofessional education of health personnel: the team approach. World Health Organization World Health Organization Technical Report Series. Geneva. 1988;769:1-72.

3 Centre for Advancement in Interprofessional Education (CAIPE). Interprofessional education – a definition. 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2007, from http://www.caipe.org.uk/

4 Hammick M., Freeth D., Koppel I., Reeves S., et al. A best evidence systematic review of interdisciplinary education. Med Teach. 2007;29:735-751.

5 Kolarik L.K., Walker G., Arnold R.M. Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1949-1954.

6 Dickens D.S. Building competence in pediatric end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:617-622.

7 Reeves S., Freeth D. The London training ward: an innovative interprofessional learning initiative. J Interprof Care. 2002;16:41-52.

8 Mu K., Chao C., Jensen G., et al. Effects of interprofessional rural training on students’ perceptions of interprofessional health care services. J Allied Health. 2004;33:125-131.

9 Nash A., Hoy A. Terminal care in the community: an evaluation of residential workshops for general practitioner/district nurse teams. Palliat Med. 1993;7:5-17.

10 Reeves S. Community-based interprofessional education for medical, nursing and dental students. Health Soc Care Community. 2000;4:269-276.

11 Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001.

12 Interprofessional Education Consortium (IPEC). Creating, Implementing, and Sustaining Interprofessional Education, volume III of a series. San Francisco: Stuart Foundation, June, 2002. [Electronic version]

13 Vesel T: Personal Communication, Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Children’s Hospital Boston – Pediatric interdisciplinary palliative care fellowship.

14 Kersun L., Gyi L., Morrison W.E. Training in difficult conversations: a national survey of pediatric hematology-oncology and pediatric critical care physicians. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:525-530.

15 Tucker K., Wakefield A., Boggis C., et al. Learning together: clinical skills teaching for medical and nursing students. Med Educ. 2003;37:630-637.

16 Fineberg I.C., Wenger N.S., Forrow L. Interdisciplinary education: evaluation of palliative care training for pre-professionals. Acad Med. 2004;79:769-776.

17 Carpenter J., Hewstone M. Shared learning for doctors and social workers: evaluation of a programme. Br J Soc Work. 1996;26:239-257.

18 Health Canada: Interprofessional Education on Patient Centered Collaborative Practice (IECPCP). Available at http://hcsc.gc.ca/english/hhr/research-synthesis.html. Accessed April 15, 2007

19 Morey J.C., Simon R., Jay G.D., et al. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1553-1581.

20 Morison S., Boohan M., Jenkins J., et al. Facilitating undergraduate interprofessional learning in healthcare: comparing classroom and clinical learning for nursing and medical students. Learn Health Soc Care. 2003;2:92-104.

21 Swinney R., Yin L., Lee A., et al. The role of support staff in pediatric palliative care: their perceptions, training and available resources. J Palliat Care. 2007;23:4-50.

22 Quinn K., Hudson P., Ashby M., et al. Palliative care: the essentials. Evaluation of a multidisciplinary education program. J Palliat Care. 2008;11:1122-1129.

23 Kilminster S., Hale C., Lascelles M., et al. Learning for real life: patient-focused interprofessional workshops offer added value. Med Educ. 2004;38(7):717-726.

24 Heller K., Solomon M.Z. Continuity of care and caring: what matters to parents of children with life-threatening conditions. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(5):335-346.

25 Browning D. To show our humanness: relational and communicative competence in pediatric palliative care. Bioethics Forum. 2002;18(3–4):23-28.

26 Bluebond-Langer M., Belasco J.B., Goldman A., Belasco C. Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. JCO. 2007;25(27):2414-2419.

27 Sourkes B., Frankel L., Brown M., et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35(9):350-386.

28 Web-site New York University School of Medicine – Medical Humanities Program. http://medhum.med.nyu.edu/.

29 Globe and Mail Web-site with Ian Brown’s Boy in the Moon Series. http://v1.theglobeandmail.com/boyinthemoon/.. Last accessed November 12, 2009

30 McFadyen A.K., Webster V.S., Maclaren W.M. The test-retest reliability of a revised version of the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS). J Interprof Care. 2006;20:633-639.

31 Fineberg I.C. Preparing professionals for family conferences in palliative care: evaluation results of an interdisciplinary approach. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:857-866.

Pediatric Pain Master Classwww.childrensmn.org/services/PainPalliative Care

The Association for Children’s Palliative Care. www.act.org.uk/

The Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care www.ippcweb.org

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization www.nhpco.org

ChIPPS curriculum www.nhpco.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3409

The Canadian Network of Palliative Care for Children www.cnpcc.ca

End of life/Palliative Education Resource Center www.eperc.mcw.edu.

The Ian Anderson Continuing Education Program in End of Life Care www.cme.utoronto.ca/endoflife

The Canadian Virtual Hospice www.virtualhospice.ca

Education for Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) www.epec.net

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital www.cure4kids.org

American Association of Colleges of Nursing/End of life Education Consortium www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec/curriculum.htm

Texas Cancer Council/Texas Children’s Hospital www.childendof-lifecare.org

Harvard Medical School: Center for Palliative Care www.hms.harvard.edu/pallcare/pcep.htm

Griefworks www.griefworks.com

Centering Corporation www.centeringcorp.com

List-serv or discussion of topics related to pediatric palliative care List-serv or discussion of topics related to pediatric palliative care: paedpalcare@act.org.uk