CHAPTER 33 Intercostal block

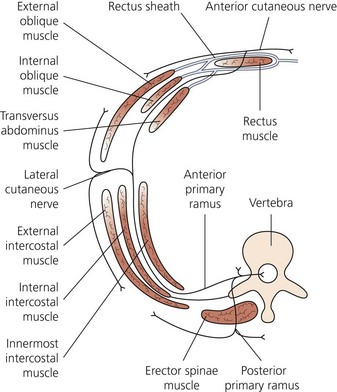

Clinical anatomy

The intercostal nerves contribute and receive sympathetic fibers. Shortly after exit from the intervertebral foramina, the dorsal rami become a posterior cutaneous branch to skin and muscles in the paravertebral region (Fig. 33.1). At the angle of the ribs, a lateral cutaneous and a collateral branch arise. The collateral branch follows the lower border of the space in the same intermuscular interval as the main trunk, which it may or may not rejoin before it is distributed as an additional anterior cutaneous branch. The lateral branch accompanies the main trunk for a time before piercing the intercostal muscles obliquely. The main trunk continues anteriorly as the anterior cutaneous branch.

The interior lower edge of the ribs provides a channel for the intercostal nerve and its companion artery and vein. The nerve lies just behind the lower border of the rib. Near the midaxillary line, the groove becomes less well defined, and the nerve migrates away from the rib (Fig. 33.2). The structures between skin and intercostal nerve vary, depending on body wall location on the nerve’s path. At the back of the chest, the nerve lies between the pleura and the posterior intercostal membrane (extension of internal intercostal muscle), but in most of its course it runs between the internal intercostal muscles and the intercostalis intimi. Where the latter muscles are absent, the nerve lies in contact with the parietal pleura. In the intercostal groove, the vein lies superior, with the artery and nerve more inferiorly. This relation is not consistent, particularly in the paravertebral region.

Surface anatomy

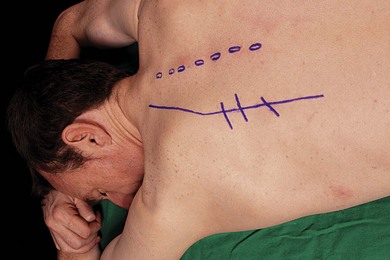

Important bony structures relevant to the intercostal nerve block include the thoracic spinous processes, paraspinal muscles, posterior angulation of ribs, spine, and inferior tip of scapula. The lateral edge of the paraspinal muscles is identified and marked. This is at the posterior angle of the ribs. These lines angle medially in the upper thoracic region so as to parallel the medial edge of the scapula. The midline spinous processes are also marked. The inferior edges of the ribs are palpated and marked. At the intersection of lines are the needle insertion points (Fig. 33.3).

Sonoanatomy

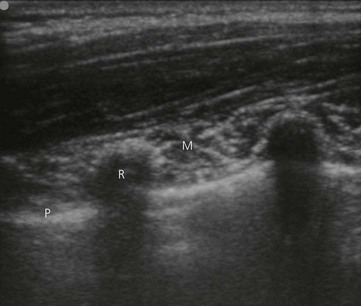

The chest wall is best imaged in a coronal (vertical) plane. Using a 6–13 MHz linear transducer, the relevant intercostal space is visualized. The ribs appear as dense dark oval structures with a bright surface (periosteum; Fig. 33.4). A dark shadow is cast deep to the rib on ultrasound, illustrating the phenomenon of echo shadowing. Echo shadowing is an echo-free zone immediately behind a structure of high absorbance or reflectivity, such as bone, calculi or metal prosthesis. The pleura and lungs are visualized deep to the intercostal space between the echo shadows (Fig. 33.4).

Technique

Landmark-based approach

The needle insertion point is infiltrated with local anesthetic using a 25-G needle. The index and third finger of the left hand retract skin up and over the rib. A 30-mm 23-G needle is introduced in a 20° cephalad orientation through the skin between the tips of the retracting fingers, and advanced until it contacts the rib (Fig. 33.5). The left hand now holds the needle hub and shaft between the thumb, index finger, and middle finger. The left-hand hypothenar eminence is firmly placed against the patient’s back. The needle and syringe move as a whole. This allows maximal control of needle depth as the left hand ‘walks’ the needle off the inferior margin of the rib and into the intercostal groove. At a distance of 2–4 mm past the edge of the rib, 3–5 mL of local anesthetic is injected after aspiration (Fig. 33.6). The intercostal block may also be performed in the midaxillary line, but there is risk of not blocking the lateral cutaneous branch.

Ultrasound-guided approach

The patient is placed in the lateral position with the side to be blocked uppermost (Fig. 33.7). The operator stands or sits behind the patient. The relevant intercostal space(s) are palpated and marked at the lateral edge of the paraspinal muscles. This landmark corresponds to the posterior angle of the ribs. Blockade at this point ensures the lateral cutaneous branch is included in the block.

The intercostal space is generally found at a depth of 2–3 cm from the skin. A coronal image of the chest wall is obtained and the ribs, pleura, and lungs identified (Fig. 33.4). The uppermost rib is kept in the centre of the field of view. The needle entry site is at the caudad edge of the linear transducer. A 23-gauge needle is advanced under real-time ultrasound guidance and local anesthetic is deposited along the needle entry path. A free hand technique rather than the use of a needle guide is preferred. A 21-GA × 50-mm insulated needle (B. Braun, Bethlehem PA) is inserted parallel to the axis of the beam of the ultrasound transducer (Fig. 33.8). The needle is attached to sterile extension tubing, which is connected to a 20-mL syringe and flushed with local anesthetic solution to remove all air from the system. It is then introduced at the caudad edge of the transducer and visualized along its entire path to the intercostal space. It is important not to advance the needle without good visualization. This may require needle or transducer adjustment.

The needle is advanced toward the inferior border of the rib (Fig. 33.9). On contacting the rib, the needle is redirected inferiorly to pass no more than 0.5 cm beyond the inferior rib margin. Following a negative aspiration test, 2–5 mL of local anesthetic agent is injected and visualized filling the intercostal space.

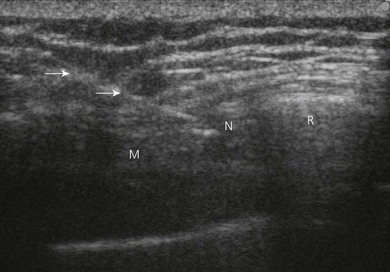

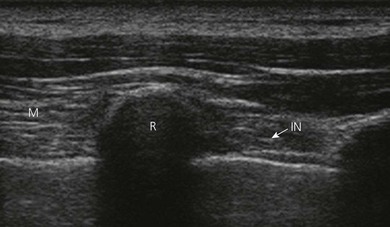

With the technique described above, the intercostal nerve is not seen with ultrasound. It can be seen, however, after leaving the intervertebral foramen (Fig. 33.10).

Adverse effects

Murphy DF. Continuous intercostal nerve block. Anesthesiology. 1986;64(5):669-670.

Rendina EA, Ciccone AM. The intercostal space. Thorac Surg Clin. 2007;17(4):491-501.

Rozen WM, Tran TM, Ashton MW, et al. Refining the course of the thoracolumbar nerves: a new understanding of the innervation of the anterior abdominal wall. Clin Anat. 2008;21(4):325-333.

Shanti CM, Carlin AM, Tyburski JG. Incidence of pneumothorax from intercostal nerve block for analgesia in rib fractures. J Trauma. 2001;51:536-539.