Chapter 33 Intellectual Disability

Definition

The IDEA requires that the cognitive dysfunction affect school performance.

The requirement for adaptive behavior deficits is the most controversial aspect of the diagnostic formulation. The controversy centers on 2 broad areas: whether impairments in adaptive behavior are necessary for the construct of intellectual disability and what to measure. The adaptive behavior criterion may be irrelevant for many children; adaptive behavior is impaired in virtually all children who have IQ scores <50. The major utility of the adaptive behavior criterion is to confirm intellectual disability in children with IQ scores in the 65-75 range. It should be noted that deficits in adaptive behavior are often found in disorders such as Asperger syndrome (Chapter 28) and ADHD (Chapter 30) in the presence of typical intellectual function.

The most commonly used medical diagnostic criteria for intellectual disability are those contained in the DSM-IV-TR (Table 33-1). The classification of intellectual disability that results from these definitions has been criticized for depending on IQ test performance rather than adaptive behavior, not taking the standard error of measurement into account, and not being predictive of outcomes for individuals. A new edition is currently being prepared that might address these issues. The AAIDD has proposed a different classification system. Instead of defining degrees of deficit (mild to profound), the AAIDD definition substitutes levels of support required in areas of adaptive function (intermittent, limited, extensive, or pervasive). The reliability of this approach has been challenged, and it blurs the distinction between intellectual and other developmental disabilities (communication disorder, autism, specific learning disabilities).

Table 33-1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY

Code based on degree of severity reflecting level of intellectual impairment:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 49, reprinted by permission.

Etiology

In children with severe intellectual disability, a biologic cause (most commonly prenatal) can be identified in >75% of cases. Causes include chromosomal (e.g., Down syndrome Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, deletion 1p36 syndrome) and other genetic and epigenetic disorders (e.g., fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes), abnormalities of brain development (e.g., lissencephaly), and inborn errors of metabolism or neurodegenerative disorders (e.g, mucopolysaccharidoses) (Table 33-2). Consistent with the finding that disorders that alter early embryogenesis are the most common and severe, the earlier the problem occurs in development, the more severe its consequences tend to be.

Table 33-2 IDENTIFICATION OF CAUSE IN CHILDREN WITH SEVERE INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY

| CAUSE | EXAMPLES | PERCENT OF TOTAL |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal disorder |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; HIE, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; PKU, phenylketonuria; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia.

Modified from Stromme P, Hayberg G: Aetiology in severe and mild mental retardation: a population based study of Norwegian children, Dev Med Child Neurol 42:76–86, 2000.

Epidemiology

Unlike mild intellectual disability, where the prevalence may be decreasing, the occurrence of severe intellectual disability has not changed appreciably since the 1940s and is 0.3-0.5% of the population. Many of the causes of severe intellectual disability involve genetic or congenital brain malformations that can neither be anticipated nor treated at present. In addition, new populations with severe intellectual disability have offset the decreases in the prevalence of severe intellectual disability that have resulted from improved health care. Although prenatal diagnosis and subsequent pregnancy terminations have resulted in a decreased prevalence of Down syndrome (Chapter 76), and newborn screening with early treatment has virtually eliminated intellectual disability caused by phenylketonuria and congenital hypothyroidism, an increased prevalence of maternal prenatal drug use (Chapter 90.4) and improved survival of very low birthweight premature infants has counterbalanced this effect.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The programming of the central nervous system (CNS) involves a process of induction; CNS maturation is defined in terms of genetic, molecular, autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine influences. Receptors, signaling molecules, and genes are critical to brain development. The maintenance of different neuronal phenotypes in the adult brain involves the same genetic transcripts that play a crucial role during fetal development, with activation of similar intracellular signal transduction mechanisms. Several syndromes that were thought to involve complex chromosomal abnormalities are, in fact, caused by single gene mutations involving induction. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome (Chapter 76), a disorder marked clinically by broad thumbs and great toes, characteristic facies, and severe intellectual disability, has been shown to result from a mutation in the gene encoding for the transcriptional co-activator CREB binding protein (CBP), a factor important in the control of gene expression in early embryogenesis.

Clinical Manifestations

Most children with intellectual disability do not keep up with their peers and fail to meet age-expected norms. In early infancy, failure to meet age-appropriate expectations can include a lack of visual or auditory responsiveness, unusual muscle tone (hypo- or hypertonia) or posture, and feeding difficulties. Between 6 and 18 mo of age, gross motor delay (lack of sitting, crawling, walking) is the most common complaint. Language delay and behavior problems are common concerns after 18 mo (Table 33-3). Earlier identification of atypical development is likely to occur with more severe impairments; and intellectual disability is usually identifiable by age 3 yr.

Table 33-3 COMMON PRESENTATIONS OF INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY BY AGE

| AGE | AREA OF CONCERN |

|---|---|

| Newborn |

Laboratory Findings

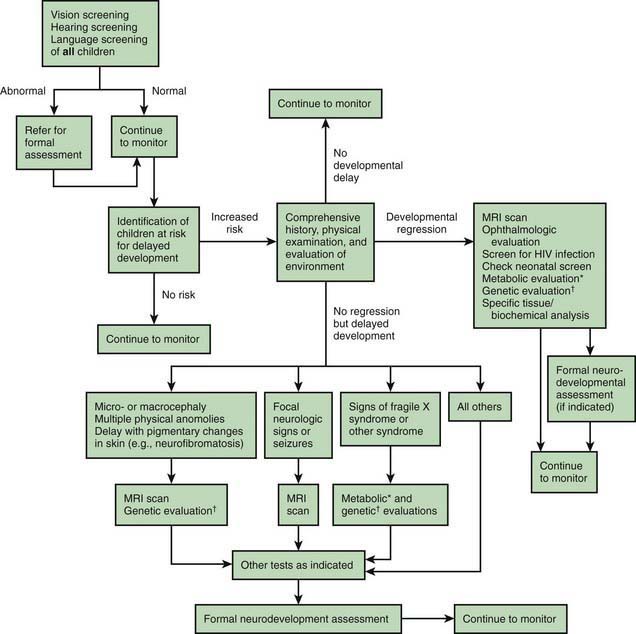

The most commonly used medical diagnostic testing for children with intellectual disability include neuroimaging; metabolic, genetic, and chromosomal testing; microarray analysis; and electroencephalography (EEG). These tests should not be used as screening tools for all children with an intellectual disability. In some children, there is a reasonable yield for testing, whereas in others the yield of <1% does not support its use. Decisions on diagnostic testing should be based on the medical and family history, physical examination, testing by other disciplines, and the family’s wishes (Fig. 33-1). Table 33-4 summarizes clinical practice guidelines that have been published to assist in evaluating the child with global developmental delay or intellectual disability. Karyotyping, particularly focusing on the number of chromosomes, duplications, deletions, or chromosomal translocations and the subtelomeric region (a hot spot), is indicated in children with multiple anomalies or a positive family history. Microarray analysis for copy number variation detects deletions and duplications when traditional chromosome banding techniques are normal and should be performed if a normal karyotype is reported and other tests are unrevealing. Deletion 1p36 syndrome, the most common subtelomeric microdeletion syndrome (1 : 5,000 births), accounts for ∼1% of children with developmental disabilities and is characterized by failure to thrive, microcephaly, deep-set eyes, midface hypoplasia, broad nasal bridge, heart deficits, and CNS anomalies. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy and seizures are also noted. The diagnosis is made by standard chromosomes in only ∼20% and requires fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) or microarray comparative genomic hybridization methods for remaining patients.

Table 33-4 SUGGESTED EVALUATION OF THE CHILD WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY/GLOBAL DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY

| TEST | COMMENT |

|---|---|

| In-depth history | Includes pre-, peri- and postnatal events (including seizures); developmental attainments; and 3-generation pedigree in family history |

| Physical examination |

CGH, comparative genomic hybridization; EEG, electroencephalogram; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Based on Curry et al, 1997; Shapiro BK, Batshaw ML: Mental retardation. In Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, et al: Gellis and Kagan’s current pediatric therapy, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2005, WB Saunders, used with permission; and Shevell M, Ashwal S, Donley D, et al: Practice parameter: evaluation of the child with global developmental delay, Neurology 60:367–380, 2003.

Differential Diagnosis

Before making the diagnosis of intellectual disability, other disorders that affect cognitive abilities and adaptive behavior should be considered. These include conditions that mimic intellectual disability and others that involve intellectual disability as an associated impairment. Sensory deficits (severe hearing and vision loss), communication disorders, and poorly controlled seizure disorders can mimic intellectual disability; certain progressive neurologic disorders can appear as intellectual disability before regression is appreciated. More than half of children with cerebral palsy (Chapter 591.1) or autism spectrum disorders (Chapter 28) also have intellectual disability as an associated deficit. Differentiation of isolated cerebral palsy from intellectual disability relies on motor skills being more affected than cognitive skills and on the presence of pathologic reflexes and tone changes. In autism spectrum disorders, language and social adaptive skills are more affected than nonverbal reasoning skills, whereas in intellectual disability there are usually more equivalent deficits in social, motor, adaptive, and cognitive skills.

Diagnostic Psychologic Testing

The most commonly used test of adaptive behavior is the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS), which involves semistructured interviews with parents and/or caregivers and teachers that assess adaptive behavior in four domains: communication, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills. Other tests of adaptive behavior include the Woodcock-Johnson Scales of Independent Behavior—Revised, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability Adaptive Behavior Scale (ABS-2nd edition) and the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS-2nd edition). There is usually (but not always) a good correlation between scores on the intelligence and adaptive scales. Basic adaptive abilities (feeding, dressing, hygiene) are more responsive to remedial efforts than is the IQ score. Adaptive abilities are also more variable, which can relate to the underlying condition and to environmental expectations. Although persons with Prader-Willi syndrome (Chapter 76) have stability of adaptive skills through adulthood, those with fragile X syndrome (Chapter 76) may have increasing deficits over time.

Complications

The most common associated deficits are motor impairments, behavioral and emotional disorders, medical complications, and seizures. The more severe the intellectual disability, the greater are the number and severity of associated impairments. Knowing the cause of the intellectual disability can help predict which associated impairments are most likely to occur. Fragile X syndrome and fetal alcohol syndrome (Chapter 100.2) are associated with a high rate of behavioral disorders; Down syndrome has many medical complications (hypothyroidism, celiac disease, congenital heart disease, atlantoaxial subluxation). Associated impairments can require ongoing physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, adaptive equipment, glasses, hearing aids, and medication. Failure to identify and treat these impairments adequately can hinder successful habilitation and result in difficulties in the school, home, and/or neighborhood environment.

Prevention

Examples of primary programs to prevent intellectual disability include:

Treatment

Although intellectual disability is not treatable, many associated impairments are amenable to intervention and therefore benefit from early identification. Most children with an intellectual disability do not have a behavioral or emotional disorder as an associated impairment, but challenging behaviors (aggression, self-injury, oppositional defiant behavior) and mental illness (mood and anxiety disorders) occur with greater frequency in this population than among children with typical intelligence. These behavioral and emotional disorders are the primary cause for out-of-home placements, reduced employment prospects, and decreased opportunities for social integration. Some behavioral and emotional disorders are difficult to diagnose in children with more severe intellectual disability because of the child’s limited abilities to understand, communicate, interpret, or generalize. Other disorders are masked by the intellectual disability. The detection of ADHD (Chapter 30) in the presence of moderate to severe intellectual disability may be difficult, as may be discerning a thought disorder (psychosis) in someone with autism and intellectual disability.

Supportive Care and Management

Primary Care

For children with an intellectual disability, primary care has a number of important components:

Prognosis

The long-term outcome of persons with intellectual disability depends on the underlying cause, the degree of cognitive and adaptive deficits, the presence of associated medical and developmental impairments, the capabilities of the families, and the school and community supports, services, and training provided to the child and family (Table 33-5). As adults, many persons with mild intellectual disability are capable of gaining economic and social independence with functional literacy. They might need periodic supervision, especially when under social or economic stress. Most live successfully in the community, either independently or in supervised settings. Life expectancy is not adversely affected by intellectual disability itself.

Table 33-5 SEVERITY OF INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY AND ADULT AGE FUNCTIONING

| LEVEL | MENTAL AGE AS ADULT* | ADULT ADAPTATION |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 9-11 yr | Reads at 4th-5th grade level; simple multiplication and division; writes simple letter, lists; completes job application; basic independent job skills (arrive on time, stay at task, interact with coworkers); uses public transportation, might qualify for driver’s license; keeps house, cooks using recipes |

| Moderate | 6-8 yr | Sight-word reading; copies information, e.g., address from card to job application; matches written number to number of items; recognizes time on clock; communicates; some independence in self-care; housekeeping with supervision or cue cards; meal preparation, can follow picture recipe cards; job skills learned with much repetition; uses public transportation with some supervision |

| Severe | 3-5 yr | Needs continuous support and supervision; might communicate wants and needs, sometimes with augmentative communication techniques |

| Profound | <3 yr | Limitations of self-care, continence, communication, and mobility; might need complete custodial or nursing care |

* International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (World Health Organization).

From Dr. Robert L. Schum, Grand Rounds Presentation at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, 2003.

For persons with moderate intellectual disability, the goals of education are to enhance adaptive abilities and “survival” academic and vocational skills so they are better able to live in the adult world (see Table 33-5). The concept of supported employment has been very beneficial to these individuals; the person is trained by a coach to do a specific job in the setting in which the person is to work. This bypasses the need for a sheltered workshop experience and has resulted in successful work adaptation in the community for many people with an intellectual disability. These persons generally live at home or in a supervised setting in the community.

As adults, people with severe to profound intellectual disability usually require extensive to pervasive supports (see Table 33-5). These individuals may have associated impairments, such as cerebral palsy, behavioral disorders, epilepsy, or sensory impairments, that further limit their adaptive functioning. They can perform simple tasks in supervised settings. Most people with this level of intellectual disability are able to live in the community with appropriate supports.

Allen-Leigh B, Katz G, Rangel-Eudave G, et al. View of Mexican family members on the autonomy of adolescents and adults with intellectual disability. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50(suppl 2):s213-s221.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. Pediatrician’s role in the development and implementation of an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and/or an Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP). Pediatrics. 1999;104:124-127.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Batshaw ML, Shapiro BK, Farber MLZ. Developmental delay and intellectual disability. In: Batshaw ML, Pellegrino L, Roizen NJ, editors. Children with disabilities. ed 6. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2007:245-262.

Battaglia A, Hoyme HE, Dallapiccola B, et al. Further delineation of deletion 1p36 syndrome in 60 patients: a recognizable phenotype and common cause of developmental delay and mental retardation. Pediatrics. 2008;121:404-410.

Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-420.

Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, et al. Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal nonsyndromic mental retardation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:599-605.

Johnson CP, Walker WOJr, Palomo-Gonzales SA, et al. Mental retardation: diagnosis, management, and family support. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2006;36:123-171.

Moeschler JB. Genetic evaluation of intellectual disabilities. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2008;15(1):2-9.

Rao LG. Education of persons with intellectual disabilities in India. Salud PublicaMe. 2008;50(Suppl 2)):s205-s212.

Roeleveld N, Zielhuis GA, Gabreëls F. The prevalence of mental retardation: a critical review of recent literature. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:125-132.

Saha S, Barnett AG, Foldi C, et al. Advanced paternal age is associated with impaired neurocognitive outcomes during infancy and childhood. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e40.

Shapiro BK, Batshaw ML. Mental retardation. In: Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, et al, editors. Current pediatric therapy. ed 18. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2006:1250-1252.

Shevell M, Ashwal S, Donley D, et al. Practice parameter: evaluation of the child with global developmental delay. Neurology. 2003;60:367-380.

Strømme P, Hagberg G. Aetiology in severe and mild mental retardation: a population-based study of Norwegian children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:76-86.

Wilson-Costello D, Friedman H, Minich N, et al. Improved survival rates with increased neurodevelopmental disability for extremely low birth weight infants in the 1990s. Pediatrics. 2005;115:997-1003.

Yeargin-Allsopp M, Boyle C. The epidemiology of neurodevelopmental disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:113-211.