Chapter 11 Integumentary system

Eczema

Case history

James’ mother tells you that she has allergic rhinitis and had childhood asthma and eczema. She is quite concerned about James at the moment because she has personal experience of how unpleasant and stressful eczema can be.

TABLE 11.1 COMMON AREAS OF INVOLVEMENT AND CAUSES OF ALLERGIC CONTACT DERMATITIS [1–8]

| Analogy: Skin of the apple |

Have you noticed your toe/finger nails have developed ridges? (eczema)

| Analogy: Flesh of the apple | Context: Put the presenting complaint into context to understand the disease |

| AREAS OF INVESTIGATION AND EXAMPLE QUESTIONS | CLIENT RESPONSES |

| Family health | James’ mother has a history of childhood eczema, hayfever and asthma |

| Allergies and irritants | |

| Analogy: Core of the apple with the seed of ill health | Core: Holistic assessment to understand the client |

| AREAS OF INVESTIGATION AND EXAMPLE QUESTIONS | CLIENT RESPONSES |

| Emotional health | |

| Do you have any significant fears or anxieties at the moment? | Not really, just stress about school and hoping my marks will be good enough to get me into uni. |

| Stress release | |

| What are you doing to deal with your stress? | Just having down time when I can. When I’m not studying I probably spend most of my time on the computer. |

| Family and friends | |

| How do you get on with your family and friends? | Pretty good most of the time though my little sister is really annoying. I see my friends at school and we usually go out on the weekends. |

| Home life | |

| How do you feel at home? | Good. Sometimes Mum and Dad get on my nerves but they’re pretty good really. |

| Action needed to heal | |

| What do you feel you need to do to get your skin under control again? | I think something to put on it and maybe some medicine. Maybe be less stressed. |

TABLE 11.4 JAMES’ SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS [1, 2, 9]

| Pulse | 75 bpm |

| Blood pressure | 120/75 sitting |

| Temperature | 37.8°C |

| Respiratory rate | 12 resp/min |

| Body mass index | 24 |

| Waist circumference | 85.8 cm |

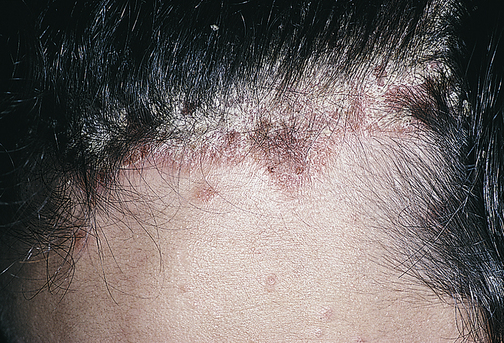

| Face | Mild erythema on cheeks and around skin line |

| Inspection of skin on the hands and body | Skin red with signs of secondary thickening and lichenification of the skin; skin trauma (excoriation) from scratching and areas of severe erythema; broken skin in skin folds of knees and elbows and joints of fingers has caused weeping of pus and showing signs of bleeding |

| Urinalysis | No abnormality detected (NAD) |

Results of medical investigations

| CONDITIONS AND CAUSES | WHY UNLIKELY |

|---|---|

| INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION | |

| Plaque psoriasis vulgaris: onset from 15 years of age is common, can cause plaques of skin on scalp, knees and elbows, can come and go and be worse at times of stress. | Scalp can be involved but usually does not spread past the hair margin; usually dry and does not have vesicles that ooze pus; presents as silvery loose scales with sharp margins; skin rash usually only on extensor surfaces of extremities; not common to have facial skin rash; more common to have arthritic involvement |

| ENDOCRINE/REPRODUCTIVE | |

| Diabetes: sometimes children with diabetes will manifest eczema-like skin rashes | Uncommon; urinalysis NAD |

Case analysis

| Not ruled out by tests/investigations already done [2–5, 9, 10, 59–68] | ||

| CONDITIONS AND CAUSES | WHY POSSIBLE | WHY UNLIKELY |

| ALLERGIES AND IRRITANTS | ||

|

Atopic eczema: the word ‘atopy’ means to react to common environmental factors; can be caused and aggravated by diet, genetic factors, heat, humidity, drying of the skin, contact with woollen clothing, animal saliva touching the skin; house dust mite allergy is thought to be an important factor in facial eczema |

||

Working diagnosis

James and eczema

Atopic eczema can be caused and aggravated by diet, genetic factors, heat, humidity, drying of the skin, contact with woollen clothing, animal saliva touching the skin and house dust. There is a strong genetic maternal link with atopic eczema and a family history of asthma may be associated. Characteristic features of eczema are red and hot skin usually in the flexures of joints such as the ankles, knees, elbows and around the neck. Swelling is common in acute stages of the rash, with weeping and oozing of fluid to the surface of skin developing after the acute stage. Crusting over of this fluid causes scaling, fissuring and excoriation that can cause intense itching. Chronic scratching can lead to secondary infections and if they are extremely bad over a large area of the body, impaired thermoregulation and increased blood flow can lead to cardiac impairment.

General references used in this diagnosis: 2–4, 59–61, 65, 68

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment for the presenting complaint and symptoms | Treatment for all associated symptoms | Treatment for mental, emotional, spiritual, constitutional, lifestyle issues and metaphysical considerations |

| TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY |

|

• Lifestyle recommendations to reduce the itching and redness of James’ skin • Lifestyle recommendations to reduce skin dryness and improve skin quality, thereby reducing irritation and itching • Recommendations to identify and eliminate or limit exposure to allergens that are triggering the eczema • Topical cream or gel to promote skin healing along with reducing inflammation and itching; also with antimicrobial properties to reduce the chance of skin infections • Physical therapy suggestions to reduce symptoms • Herbal tonic and/or tea with depurative and antiallergic properties • Nutritional supplements with anti-inflammatory and antiallergic properties to improve symptoms |

• Reduce the reactivity of James’ immune system with lifestyle, dietary, herbal and nutritional recommendations

• Dietary recommendations to reduce exposure to reactive foods

• Dietary recommendations to increase consumption of foods with anti-inflammatory properties

• Herbal tonic and/or tea with antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties

• Nutritional supplements with antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties and to improve James’ nutritional status

• Lifestyle and physical therapy suggestions to help James cope better with his stress

• Herbal tonic and/or tea with an adaptogenic and anxiolytic action to help James improve his stress response

• Nutritional supplements to provide essential nutrients for health of the nervous system and to improve James’ stress response

TABLE 11.8 DECISION TABLE FOR REFERRAL [2–5, 10, 11]

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Referral for presenting complaint | Referral for all associated physical, dietary and lifestyle concerns | Referral for contributing emotional, mental, spiritual, metaphysical, lifestyle and constitutional factors |

| REFERRAL FLAGS | REFERRAL FLAGS | REFERRAL FLAGS |

| ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE | ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE | ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE |

| REFERRAL | REFERRAL | REFERRAL |

TABLE 11.9 FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS THAT MAY BE NECESSARY [2, 3, 5, 9, 10]

| TEST/INVESTIGATION | REASON FOR TEST/INVESTIGATION |

|---|---|

| FIRST-LINE INVESTIGATIONS: | |

| Skin examination by GP/dermatologist | Clinical diagnosis of a skin disorder by sighting the skin lesions; often diagnosis made by seeing the lesion |

| Chest examination: auscultation, percussion | Signs of asthma, obstruction, infection |

| Nijmegen questionnaire | Hyperventilation syndrome |

| Food diary | To help determine any foods that may be triggering or aggravating symptoms |

| Full blood count | Any fever, bacteria or viral association with the skin rash |

| ESR/CRP blood test | Indicates level of inflammation; whether bacterial/viral cause |

| Serum IgE blood test | Atopic eczema and allergic triggers for asthma |

| Skin prick testing | Response to immediate contact allergies test for extrinsic-specific allergies |

| Skin patch tests to particular allergens | Review 2–4 days later for specific delayed contact allergies |

| Rast test (blood) | Test for ingested or inhaled antigens |

| IF NECESSARY: | |

| KOH test of skin discharge/lesion (potassium hydroxide) | |

| Wood’s lamp examination (hand-held ultraviolet light shines certain colours for specific conditions) | Fungus: fluorescent |

| Skin biopsy | Psoriasis, eczema, fungus |

| Monochromator light-testing | Photosensitive eczema |

| Antigliadin antibody blood test | Definitive test for gluten allergy |

| Lung function tests (forced expiratory volume (FEV), peak expiratory flow rate (PEF)) | Will be reduced in asthma |

| Exercise test | Asthma |

| Capnometer/pulmonary gas exchange during orthostatic tests | Hyperventilation syndrome |

Confirmed diagnosis

Atopic eczema with associated atopic asthma

Prescribed medication

TABLE 11.10 DECISION TABLE FOR TREATMENT (ONCE DIAGNOSIS IS CONFIRMED)

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment for the presenting complaint and symptoms | Treatment for all associated symptoms | Treatment for mental, emotional, spiritual, constitutional, lifestyle issues and metaphysical considerations |

| TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY |

|

• Continue with lifestyle recommendations to reduce symptoms and improve the quality of James’ skin • Continue to limit exposure to known environmental and dietary triggers • Continue to use topical herbal preparations as necessary to promote skin healing and to reduce redness, irritation, itch and to prevent infection • Continue with physical therapy recommendations as needed to manage symptoms • Continue with herbal tonic and/or tea to manage and prevent symptoms as needed • Continue with nutritional supplements to provide essential nutrients for James’ skin and reduce frequency and severity of eczema |

• Continue to focus on reducing the reactivity of James’ immune system with lifestyle, dietary, herbal and nutritional recommendations

• Support and improve James’ digestive function with herbal and nutritional supplements

• Ongoing dietary changes to improve James’ nutritional status

• Continue with dietary recommendations to increase consumption of foods with anti-inflammatory properties

• Continue with herbal tonic or tea and nutritional supplements to enhance James’ antioxidant status and modulate his immune response; review the use of herbal therapy after 2 months based on James’ symptoms and compliance to treatment

• Continue with lifestyle and physical therapy suggestions to help James manage his stress, particularly during his final year of high school

• Continue with herbal tonic and/or tea and nutritional supplements with adaptogenic and anxiolytic action and essential nutrients to support James’ stress response, particularly during his final year of high school; review the use of herbal therapy once James’ stress levels have reduced

Treatment aims

• Prevent and relieve the itch [13, 16, 31].

• Reduce the inflammatory response in James’ skin [12].

• Promote skin healing and improve the skin quality, hydration and barrier function [14, 17, 31].

• Normalise essential fatty acid and prostaglandin metabolism [12, 13, 46].

• Balance James’ immune system, normalise his TH1 and TH2 balance [12–15] and reduce excess histamine release [13].

• Identify and reduce or eliminate exposure to food and environmental allergens [13, 15, 26, 31, 49].

• Identify and reduce or eliminate exposure to other trigger factors [12, 15, 31].

• Identify and correct nutritional deficiencies [13, 14] and improve James’ diet.

• Improve James’ digestive function, intestinal microflora [14, 47, 48] and support his eliminative process [18].

• Improve James’ stress response and reduce stress levels [14, 15, 50].

• Educate James about ways to better manage his condition to improve his quality of life [16, 31, 50].

Lifestyle alterations/considerations

• Encourage James to avoid using soap or soap-based products [13, 20, 30, 31] and use pH-balanced, soap-free alternatives instead [30, 20]. He should apply moisturiser immediately after bathing [12, 20, 31].

• Encourage James to bathe in warm rather than hot water [12, 20, 31].

• James may find soaking in a tepid oatmeal bath soothes his skin and reduces itching [12].

• Encourage James to avoid wearing fabrics that irritate his skin [13, 31]. Clothing should be washed in mild soaps and rinsed thoroughly [13].

• Encourage James to determine the environmental triggers to his eczema and avoid them wherever possible [13, 31, 32]. These may include house dust mites, chemicals, perfumes in personal care products or detergents, climate and airborne allergens [13, 32].

• Testing for food or chemical sensitivities may be helpful [14, 32].

• Encourage James to try to find techniques to help him avoid scratching his skin [13, 14, 30]. Scratching damages the skin, increases the chance of infection and increases lichenification [13].

• James may benefit from stress-management techniques and/or psychotherapy to help him manage the stress-related triggers of his condition [13, 32, 50].

• Encourage James to engage in a form of physical exercise that does not aggravate his eczema. Exercise is strongly associated with decreased levels of stress, anxiety and depression [35, 36].

Dietary suggestions

• Food allergies or intolerances should be identified and managed by removing them from the diet [12–14, 26, 32]. Common allergenic foods include dairy food, wheat, eggs, citrus fruit, peanuts and soya [14, 15, 26, 38].

• Encourage James to increase his intake of omega-3 fatty acids from cold-water fish, almonds, walnuts, pumpkin and flax seed [12, 14, 20, 33]. James should eat oily fish at least three times per week [13, 14]. Omega-3 fatty acids can reduce the severity of eczema and improve skin quality [53, 54].

• Encourage James to ensure he drinks sufficient water to ensure adequate skin hydration [14, 31].

• James needs to improve his diet and increase consumption of antioxidant-rich whole foods providing adequate levels of essential nutrients and antioxidants [49, 51].

Physical treatment suggestions

• James may find massage therapy beneficial for both his symptoms of stress and his anxiety [25, 40] as well as for his eczema [26].

• James may find acupuncture therapy helpful for his anxiety symptoms [27, 28]. Acupuncture also has immune modulating effects, which may also be beneficial [29].

• Hydrotherapy: constitutional hydrotherapy to assist immune function and tone lungs [41, 42, 45]. Oatmeal half-neutral bath 20 minutes twice daily [43, 44]. Alternate hot/cold douche shower direct to thighs and upper chest to tone the body [44]. Cold sponge bath on the body before bed to ease the rash [44].

| HERB | FORMULA | RATIONALE |

|---|---|---|

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) applied topically in the form of a gel is effective in reducing redness, swelling and itch in atopic dermatitis [13, 24, 19]

Calendula (Calendula officinalis) cream is soothing and healing to the skin [12, 20]

| Can be used as an alternative to the herbal tonic or taken in conjunction with the herbal tonic as an alternative to tea and coffee | ||

| HERB | FORMULA | RATIONALE |

| 3 parts | Anti-inflammatory [20]; antioxidant [20]; depurative [22]; antiallergic [22]; traditionally used in skin conditions such as eczema [20, 22, 23]; specifically indicated for nervous eczema [23] | |

| 2 parts | Anti-inflammatory [20, 19, 13]; antioxidant [20, 19]; adrenal tonic [20, 19]; immunomodulator [20, 19]; antiallergic action [13] | |

| 2 parts | Depurative [22, 39]; traditionally used for chronic skin disorders such as eczema [22, 39] | |

| 1 part | Nervine tonic [22]; sedative [23]; indicated for use in nervous tension and anxiety [22, 23] | |

Infusion: 1 tsp per cup – 1 cup 3 times daily

TABLE 11.13 NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS

| SUPPLEMENT AND DOSE | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| High-potency practitioner-strength multivitamin, mineral and antioxidant supplement containing therapeutic doses of vitamins A, C, D and E, zinc, selenium and B-group vitamins [12–14] | Optimal levels of essential nutrients are associated with reduced symptom severity in eczema [49]; oxidative stress and altered antioxidant function is involved in acute atopic dermatitis [51]; zinc deficiency is common in atopic dermatitis [13] |

| Omega-3 fatty acids regulate inflammatory prostaglandin formation [33]; deficiency is associated with dry, itchy, peeling and flaky skin [33]; omega-3 fatty acids have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating properties that may be beneficial in atopic dermatitis [14, 20]; people with atopic dermatitis have altered essential fatty acid and prostaglandin metabolism [13]; the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids is lower in people with atopic dermatitis [13]; supplementation with 6000 mg of omega-3 oils daily improves clinical symptoms of atopic dermatitis [53, 54]; reduces plasma catecholamine levels thereby reducing anxiety levels via the HPA axis [34] | |

| Antiallergic [20, 33, 57]; antioxidant [20, 33, 57, 58]; immunomodulator [20, 57]; anti-inflammatory [20, 33, 58]; inhibits inflammatory enzymes, prostaglandins and leukotrienes [20, 57], stabilises mast cells [20, 57] and inhibits histamine release [33, 57] | |

| Moderates inflammatory and immune responses [20, 56]; strengthens intestinal barrier function [20, 56]; supplementation with probiotics may reduce the severity of symptoms in established atopic dermatitis [20, 55, 56]; effective in the primary prevention of eczema [48, 52, 55, 56] |

[1] Talley N.J., O’Connor S. Pocket Clinical Examination, third edn. Australia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009.

[2] Kumar P., Clark C. Clinical Medicine, sixth edn. London: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

[3] Seller R.H. Differential Diagnosis of Common Complaints, fifth edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

[4] Jamison J. Differential Diagnosis for Primary Care, second edn. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006.

[5] Collins R.D. Differential Diagnosis in Primary Care, fourth edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

[6] Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. Skills for Communicating with Patients, second edn. Oxford: Radcliff Publishing; 2000.

[7] Neighbour R. The Inner Consultation; how to develop an effective and intuitive consulting style. Oxon: Radcliff Publishing; 2005.

[8] Lloyd M., Bor R. Communication Skills For Medicine, third edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009.

[9] Douglas G., Nicol F., Robertson C. Macleod’s Clinical Examination, twelfth edn. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009.

[10] Pagna K.D., Pagna T.J. Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test reference, third edn. USA: Mosby; 1997. (later edition)

[11] Peters D., Chaitow L., Harris G., Morrison S. Integrating Complementary Therapies in Primary Care. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002.

[12] Jamison J. Clinical Guide to Nutrition & Dietary Supplements in Disease Management. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

[13] Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T., Joiner-Bey H. The Clinicians Handbook of Natural Medicine, second edn. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

[14] Osiecki H. The Physicians Handbook of Clinical Nutrition, seventh edn. Eagle Farm: Bioconcepts; 2000.

[15] Wilsmann-Theis D., Hagemann T., Jordan J., Bieber T., Novak N. Facing psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: are there more similarities or more differences? European Journal of Dermatology. 2008;18(2):172–180.

[16] Schmitt J., Csötönyi F., Bauer A., Meurer M. Determinants of treatment goals and satisfaction of patients with atopic eczema. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellchaft. 2008;6(6):458–465.

[17] Yosipovitch G. How to treat that nasty itch. Experimental Dermatology. 2005;14:478–479.

[18] Cook T. Effective herbal treatment of allergies. Mediherb Modern Phytotherapist. 2003;7(2):1–12.

[19] Bone K. Clinical Applications of Chinese and Ayurvedic Herbs: Monographs for the Western Herbal Practitioners. Warwick: Phytotherapy Press; 1996.

[20] Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs & Natural Supplements: An evidence based guide, second edn. Sydney: Elsevier; 2007.

[21] Mills S., Bone K. Principles & Practice of Phytotherapy; Modern Herbal Medicine. Edinburgh: London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

[22] Mills S., Bone K. The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

[23] British Herbal Medicine Association. British Herbal Pharmacopoeia. BHMAA; 1983.

[24] Saedi M., Morteza S.K., Ghoreishmi M.R. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with licorice gel. The Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 2003;14(3):153–157.

[25] Field T., Robinson G., Scafidi F., Nawrocki R., Goncalves A. Massage therapy reduces anxiety and enhances EEG pattern of alertness and math computations. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;86:197–205.

[26] Hanifin J.M., Cooper K.D., Ho V.C., Kang S., Krafchik B.R., Margolis D.J., Schachner L.A., et al. Guidelines of care for atopic dermatitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;50(3):391–404.

[27] Jorm A.F., Christensen H., Griffiths K.M., Parslow R.A., Rodgers B., Blewitt K.A. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety disorders. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;181(7):S29–S46.

[28] Spence D.W., Kayumov L., Chen A., Lowe A., Jain U., Katzman M.A., et al. Acupuncture increases nocturnal melatonin secretion and reduces insomnia and anxiety: A preliminary report. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004;16(1):19–28.

[29] Joos S., Schott C., Zou H., Daniel V., Martin E. Immunomodulatory effects of acupuncture in the treatment of allergic asthma: a randomized controlled study. J Altern Complement Med. 2000;6(6):519–525.

[30] Ruzicka T., Ring J., Przybilla B. Handbook of atopic eczema. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 198–210

[31] Cheigh N.H. Managing a common disorder in children: Atopic dermatitis. Journal of Pediatric Healthcare. 2003;17(2):84–88.

[32] Jones S.M. Triggers of atopic dermatitis. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2002;22(1):55–72.

[33] Osiecki H. The Nutrient Bible, seventh edn. Eagle Farm: BioConcepts Publishing; 2008.

[34] Ross B.M., Seguin J., Sieswerda L.E. Omega-3 fatty acids as treatments for mental illness: which disorder and which fatty acid? Lipids in Health and Disease. 2007;6:21.

[35] Jorm A.F., Christensen H., Griffiths K.M., Parslow R.A., Rodgers B., Blewitt K.A. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for anxiety disorders. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;181(7):S29–S46.

[36] Byrne A., Byrne G.D. The effect of exercise on depression, anxiety and other mood states: A review. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37(6):565–574.

[37] Kemper K.J., Lester M.R. Alternative asthma therapies:An evidence-based review. Contemporary Pediatrics. 1999;16(3):162–195.

[38] Baker J.C., Ayres J.G. Diet and asthma. Respiratory Medicine. 2000;94:925–934.

[39] Morgan M. Herbs for the oral treatment of skin conditions. A Phytotherapist’s Perspective. 2005;65:1–2.

[40] Edge J. A pilot study addressing the effect of aromatherapy massage on mood, anxiety and relaxation in adult mental health. Complementary Therapies in Nursing & Midwifery. 2003;9:90–97.

[41] Boyle W., Saine A. Lectures in Naturopathic Hydrotherapy. Oregon: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1988.

[42] Watrous L.M. Constitutional hydrotherapy: from nature cure to advanced naturopathic medicine. Journal of Naturopathic Medicine. 1997;7(2):72–79.

[43] Sinclair M. Modern Hydrotherapy for the Massage Therapist. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

[44] Buchman D.D. The complete book of water healing. New York: Contemporary Books, McGraw-Hill Companies; 2001.

[45] Blake E. Chaitow L., Blake E., Orrock P., Wallden M., Snider P., Zeff (Eds.), Naturopathic Physical Medicine J. Theory and Practice for Manual Therapists and Naturopaths. Philaldelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2008.

[46] Horrobin D.F. Essential fatty acid metabolism and its modification in atopic eczema. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;71:367S–372S.

[47] Mah K.W., Bjorksten B., Lee B.W., vanBever H.P., Shek L.P., Tan T.N., et al. Distinct pattern of commensal gut microbiota in toddlers with eczema. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2006;140(2):157–163.

[48] Ouwenhand A.C. Antiallergic Effects of Probiotics. Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137:794S–797S.

[49] Ellwood P., Asher M.I., Bjorksten B., Burr M., Pearce N. Diet and asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema symptom prevalence: an ecological analysis of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) data. European Respiratory Journal. 2001;17:436–443.

[50] Chida Y., Steptoe A., Hirakawa N., Sudo N., Kubo C. The Effects of Psychological Intervention on Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2007;144:1–9.

[51] Tsukahara H., Shibatab R., Ohshimaa Y., Todorokia Y., Satoa S., Ohtaa S., et al. Oxidative stress and altered antioxidant defenses in children with acute exacerbation of atopic dermatitis. Life Sciences. 2003;72:2509–2516.

[52] Kalliomäki M., Salminen S., Arvilommi H., Kero P., Koskinen P., Isolauri E. Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1076–1079.

[53] Soyland E., Funk J., Rajka G., Sandberg M., Thune P., Rustad L., et al. Dietary supplementation with very long-chain n-3 fatty acids in patients with atopic dermatitis. A double-blind, multicentre study. British Journal of Dermatology. 1994;130(6):757–764.

[54] Bjorneboe A., Soyland E., Bjorneboe G.E., Rajka G., Drevon C.A. Effect of n-3 fatty acid supplement to patients with atopic dermatitis. Journal of Internal Medicine Suppl. 1989;731:233–236.

[55] Caramia G., Atzei A., Fanos V. Probiotics and the skin. Clinics in Dermatology. 2008;26:4–11.

[56] Lee J., Seto D., Bielory L. Meta-analysis of clinical trials of probiotics for prevention and treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121:116–121.

[57] Shaik Y.B., Cateallani M.L., Perrella A., Conti F., Salini V., Tete S., et al. Role of quercetin (a natural herbal compound) in allergy and inflammation. Journal of Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2006;20(3–4):47–52.

[58] Boots A.W., Haenen G., Bast A. Health effects of quercetin: From antioxidant to nutraceutical. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;585:325–337.

[59] Wüthrich B., Cozzio A., Roll A., Senti G., Kündig T., Schmid-Grendelmeier P. Atopic eczema: genetics or environment? Ann Agric Environ Med. 2007;14(2):195–201.

[60] Saint-Mezard P., Rosieres A., Krasteva M., et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14(5):284–295.

[61] Buxton P.K. ABC of dermatology. Eczema and dermatitis. British Medical Journal (Clin Res Ed.). 1987;295(6605):1048–1051.

[62] Schwartz R.A., Janusz C.A., Janniger C.K. Seborrheic dermatitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(1):125–130.

[63] Heath M.L., Sidbury R. Cutaneous manifestations of nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(4):417–422.

[64] Greaves M.W. Recent advances in pathophysiology and current management of itch. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2007;36(9):788–792.

[65] Leung D.Y.M., Beiber T. Atopic Dermatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:151–160.

[66] Twycross R., et al. Itch: scratching more than the surface. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2003;96:7–26.

[67] Yosipovitch G., et al. Itch, Lancet. 2003;361:690–694.

[68] Cork M., Robinson D., Vasilopoulos Y., et al. New perspectives on epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis: Gene–environment interactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:3–21.

Psoriasis

Case history

When you ask Margaret if she has had any skin problems previously she tells you she hasn’t experienced this problem before, although she has had problems in the past with some of her toenails. She tells you she is concerned about her toenails as well and is wondering if there is any connection between the toenail problem and the patches on her skin. Margaret confides to you that she is concerned about being intimate with her new man while her skin looks the way it does.

| Analogy: Skin of the apple |

| Analogy: Flesh of the apple | Context: Put the presenting complaint into context to understand the disease |

| AREAS OF INVESTIGATION AND EXAMPLE QUESTIONS | CLIENT RESPONSES |

| Family health | Margaret’s mother had rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Occupational toxins and hazards |

Have you noticed a similar rash develop in the genital region? (psoriasis, Reiter’s syndrome)

It would help me make an assessment for how to help you if I could understand more about your sexual relationships. Do you mind me asking you some more personal questions around your sexual history?

Have you had a test for HIV before or any investigations for sexually transmitted diseases? (Reiter’s syndrome)

You may explain to the client that if she had been initimate in a relationship it could be recommended to have tests for sexually transmitted diseases.

| Analogy: Core of the apple with the seed of ill health | Core: Holistic assessment to understand the client |

| AREAS OF INVESTIGATION AND EXAMPLE QUESTIONS | CLIENT RESPONSES |

| Support systems | |

| Do you have friends or family nearby? | No, I’m here on my own. |

| Stress release | |

| How are you managing your stress at the moment? | I usually lose myself in my art or music when I’m stressed. At the moment all my gear is back home in Wales and I’m finding it difficult to do much anyway because of the soreness in my hands. |

| Family and friends | |

| Tell me about your family and friends in the UK. | I have a son and daughter back home, and three grandchildren. They say they will come and visit me if I decide to stay here. I also have some very good friends and we keep in contact through the phone and internet. |

| Home life | |

| What is your home life like at the moment? |

TABLE 11.17 MARGARET’S SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS [1, 2, 9]

| Pulse | 80 bpm |

| Blood pressure | 130/80 |

| Temperature | 37°C |

| Respiratory rate | 14 resp/min |

| Body mass index | 25 |

| Waist circumference | 82.3 cm |

| Face | Dark under the eyes, tired looking |

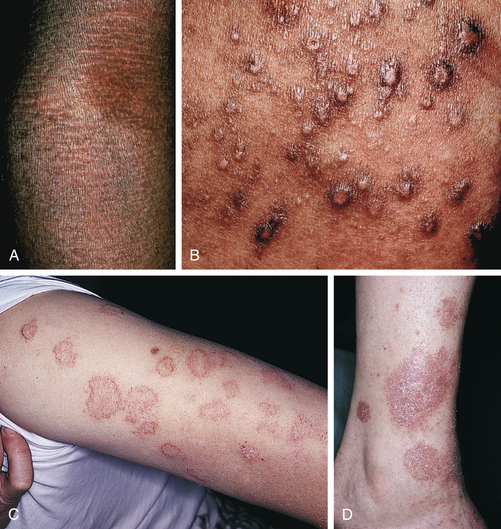

| Skin lesion on elbows and knees | Silvery loose scales with thickening of the skin (lichenification) on extensor surfaces of elbows, knees |

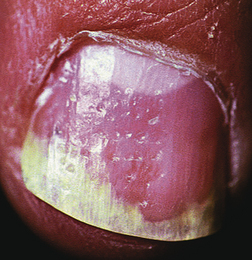

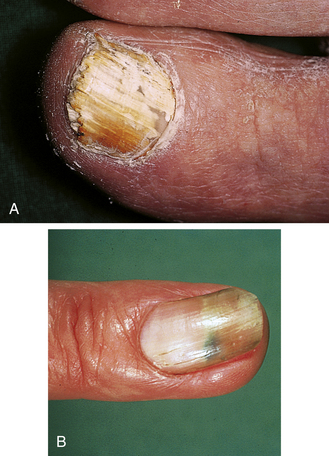

| Toenails | Appear yellow on three toe nails on left foot (finely pitted); ridging across the nails; onycholysis (lifting of nail bed) and brown stained patches |

| Urinalysis | No abnormality detected (NAD) |

TABLE 11.18 RESULTS OF MEDICAL INVESTIGATIONS [2–5, 10]

| Margaret recently had these blood tests to investigate the pain in her hands | |

| TEST | RESULTS |

| Full blood count | NAD |

| ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate indicates inflammation in general) | NAD |

| Rheumatoid factor (RH factor): in inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis IgG antibodies produced by lymphocytes in membranes act as antigens, which then react with IgG and IgM antibodies to produce immune complexes that cause inflammation and joint damage; the reactive IgM molecule is RH factor | NAD |

| Antinuclear antibodies: it is a protein antibody that reacts against cellular nuclear material and is indicative of an autoimmune abnormality; this is very sensitive in detecting systemic lupus erythematosus, but not specific to this disease as it can be present in other inflammatory and autoimmune diseases | NAD |

| HLA-B27 antigen: HLA antigens are under direct genetic control and share a locus on the chromosome; HLA-B27 is found in 90% of people with ankylosing spondylitis and Reiter’s syndrome and 70% of people with a similar spinal arthropathy with psoriasis | Detected |

TABLE 11.19 UNLIKELY DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS [2–5, 10, 53, 61]

| CONDITIONS AND CAUSES | WHY UNLIKELY |

|---|---|

| CANCER AND HEART DISEASE | |

| Solar keratosis: premalignant silvery scaly lesions in sun-exposed areas | Appear as pink macules (flat patches) that are rough like sandpaper; from long term exposure to sun and increases due to age (may not have been as exposed to as much sun in Wales as she is in Australia) |

| DEGENERATIVE AND DEFICIENCY | |

| Anaemia: iron deficiency can cause a generalised itch | Full blood count NAD |

| Anaemia of chronic disease: can develop in rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory systemic conditions regardless of high dietary levels of iron | Full blood count NAD |

| INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION | |

| Atopic dermatitis or eczema: can present with scaling and lichenification (thickening of skin); presenting in folds of knees, elbows, face, hair margin and toe nails; lesions cause some irritation and scratching; lesions worse for anxiety; lesions can be widespread; can present with pitted nail bed in toes and fingers; ridging across the nails | Usually extremely itchy and symmetrical; common to begin in childhood; often family history of allergic rhinitis or asthma; no oozing vesicles; coarse pitted nail bed often associated with weeping skin lesion on toes; skin rash usually in flexor surfaces only; arthritic involvement is not a feature of eczema |

| Pityriasis rosea: can present like psoriasis with scaling plaques or patches after recurrent scratching; red scales with clear centre and symmetrical; usually resolves within 6 weeks | Usually on trunk and extremities; can be itchy; more common in winter; oval pink patches that are macula (flat discoloured area); usually presents in children and young adults; large solitary herald patch on the trunk develops before generalised lesions |

| Erythrodermic psoriasis: generalised psoriatic rash that can affect all body sites, including the hands, feet, nails and extremities | Need to clarify if Margaret has ever smoked cigarettes and, if so, how many per day; can also include the face, trunk; pustular psoriasis is common feature and this form can be life threatening; often associated with fever, fatigue and circulation disorders; usually a burning sensation is reported |

| AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis: skin rash and inflammatory symptoms, sore hands, fingers and back, genetic link | No RH factor |

| Systemic lupus disease: facial rash and inflammatory arthritis [53] | No antinuclear antibodies |

| Ankylosing spondylitis: skin rash and sore back | ESR not raised |

| Reiter’s syndrome: reactive arthritis that is autoimmune in response to another infection in body; pustular dermatitis with inflamed joints; can be sexually transmitted | ESR not raised, no presenting fever, no conjunctivitis or urinary tract inflammation typically associated with inflamed joints |

Case analysis

| Not ruled out by tests/investigations already done [2–5, 9, 10, 52–62] | ||

| CONDITIONS AND CAUSES | WHY POSSIBLE | WHY UNLIKELY |

| ALLERGIES AND IRRITANTS | ||

| Nummular eczema (discoid) | Similar appearance to psoriasis with scaling plaques on the elbows and knees; can present in adults or children; can be anywhere including the hands and especially the limbs; can present in atopic or non-atopic clients; acute/subacute presentations common | Usually oozing of lesions is a common symptom; not clear whether symptoms are the beginning stage of a chronic skin condition or subacute and self-limiting |

| Contact dermatitis | Present asymmetrically in exposed areas; on areas of the body that have close contact with irritants and where chemicals may be applied on the skin; can present in adults and children; possible reaction to materials used for artwork | No reported oozing vesicles as is common in contact dermatitis; need to determine if the skin rash only developed when having a break from artwork while travelling in Australia |

| Shoe dermatitis: due to chrome in leather tanning | Red scaling of the feet and toes; can occur in adults or children | |

| TRAUMA AND PRE-EXISTING ILLNESS | ||

| Trauma (strains, sprains, tear, herniated disc, fracture, disc prolapse) | Work strain and lower back pain | |

| Congenital disorders: scoliosis | Lower back pain | Need to determine how long the back pain has been experienced |

| OCCUPATIONAL TOXINS AND HAZARDS | ||

| Faulty posture | Strain for long periods of time while painting and sculpting, playing flute | |

| Repetitive strain injury (RSI) | Strain for long periods of time while painting and sculpting, playing flute | |

| INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION | ||

| Plaque psoriasis vulgaris: elbows, knees, hair margin, toenails | Mechanical irritation due to scratching lesions and repetitive actions in art work, stress and anxiety, genetic inheritance of HLA-B27 antigen, pink colour, scaly appearance; rarely on the face; arthritis in distal joints common; often present in adults; usually lesions stop at the hairline; silver scales; yellow pitted nail and lifting of nail bed common on surface of nails for those with psoriasis; brown stained patches on some nail beds; ridging across the nails; can present as red scaly patches with clear centre that weep silvery foam cells; lesions can be widespread and commonly on extensor surfaces Check if Margaret has been prescribed lithium, antimalarials or beta-blockers recently, which can make psoriasis worse | |

| Psoriatic arthritis: HLA-B27 detected | Pain in the joints of the hands that is not symmetrical, presents like RA but there is no RH factor involved, ESR readings can be normal | |

| Parapsoriasis: cutaneous disease that resembles psoriasis but does not share pathogenesis; slightly scaly, light salmon-coloured patches that measure less than 5 cm in diameter | Scaling of skin | Usually over the trunk and extremities |

| Hepatic psoriasis | Psoriasis skin presentation; scaling of skin, thickening of skin on extensor surfaces | Usually develops from chronic long-term hepatic dysfunction; no jaundice observed |

| Lichen simplex/nodular prurigo (neurodermatitis) | Scaling of skin, thickening of skin on extensor surfaces; more common in females; emotional stress can potentiate this skin disorder | Usually develops due to extremely itchy skin rash that causes intense scratching and rubbing |

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis: affects those areas of the skin where there are sebaceous glands such as the face and scalp and occurs more with times of stress [52] | Can present like psoriasis with scaling patches; common in adults | May involve scalp but usually beyond hairline; yellow scales; can be orange-red patches; not well-defined borders and greasy scales; more common as associated symptom of serious illness such as Parkinson’s disease and HIV in elderly and adults |

| Dyshidrotic eczema: on feet | Present in adults, itching vesicles; pitting of nails; ridging across the nails | Need to determine if lesions on toes began with feet/toes breaking out in blisters; common to be coarse pitting if present |

| Osteoporosis | Pain in back | More common to develop in older age group |

| Osteoarthritis | Distal interphalangeal joints most affected, not asymmetrical; not associated with increase in ESR, RH factor and antinuclear antibodies are negative; more common over 60 years of age | |

| Tinea unguium: fungal infection of the nails | Nail that is lifting off the nail bed; nails may appear yellow | Nail bed may not be pitted; usually thickening of nail bed with white or brown discolouration; white crumbly material develops under nail bed that can be tested |

| Tinea pedis: fungal infection of the feet, between toes | Scaling plaques can appear like psoriasis or nummular eczema; lesions have defined border; scaling, vesicles and itching; fungal infection of one or more toe nails can develop | Determine if itch is worse in heat; usually red scaly patches with clear centre and getting red at the edge; not silvery scales |

| Candida: toe nail | Nail bed disorder on toes | Determine if nail bed is ridged |

| SUPPLEMENTS AND SIDE EFFECTS OF MEDICATIONS | ||

| Causal factor: Drug-induced psoriasis: may be induced by beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, captopril, glyburide, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, interleukens, interferons and lipid-lowering drugs | Lithium, antimalarials, beta-blockers most common and cause psoriasis-like rash | Margaret has not mentioned prescribed medication in initial history taking |

| STRESS AND NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE | ||

| Causal factor: Neurotic excoriations | Thickening of skin and excoriation on extensor surface of knees and elbows | Nervous habit of scratching causes lesions; can develop in childhood |

Working diagnosis

Margaret and psoriasis

General references used in this diagnosis: 2–4, 55, 56, 58, 60–62

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment for the presenting complaint and symptoms | Treatment for all associated symptoms | Treatment for mental, emotional, spiritual, constitutional, lifestyle issues and metaphysical considerations |

| TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY |

|

• Lifestyle recommendations to reduce skin dryness and improve skin quality • Topical herbal preparations to reduce inflammation, soften lesions and improve skin quality • Physical treatment and lifestyle suggestions to reduce symptoms and improve skin quality • Physical treatment and lifestyle suggestions to reduce trigger factors such as stress and exposure to environmental factors • Physical treatment suggestions to help reduce hand pain and stiffness • Herbal tonic and tea to improve skin function and reduce symptoms of psoriasis • Nutritional supplements to improve skin quality and reduce symptoms of psoriasis |

• Recommendations to identify and manage dietary and/or environmental sensitivities or allergies

• Dietary recommendations to improve general health, liver and bowel function

• Dietary recommendation to include foods with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immune-modulating properties

• Herbal tonic and tea containing herbs to support liver and bowel function and modulate immune response

• Nutritional supplements to improve general health, improve bowel health, reduce inflammation and improve skin quality

TABLE 11.22 DECISION TABLE FOR REFERRAL [2–5, 10, 11]

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Referral for presenting complaint | Referral for all associated physical, dietary and lifestyle concerns | Referral for contributing emotional, mental, spiritual, metaphysical, lifestyle and constitutional factors |

| REFERRAL FLAGS | REFERRAL FLAGS | REFERRAL FLAGS |

| Nil | ||

| ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE | ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE | ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE |

| Nil | ||

| REFERRAL | REFERRAL | REFERRAL |

TABLE 11.23 FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS THAT MAY BE NECESSARY [2, 3, 5, 9, 10]

| TEST/INVESTIGATION | REASON FOR TEST/INVESTIGATION |

|---|---|

| FIRST-LINE INVESTIGATIONS: | |

| Skin examination by GP/dermatologist | Clinical diagnosis of skin disorder by sighting skin lesions; often diagnosis made by sight of lesion |

| Full blood count | Infectious disease |

| Serum IgE levels | Allergic disease, atopic eczema |

| IF NECESSARY: | |

| Potassium hydroxide (KOH) test | |

| Wood’s lamp examination (hand-held ultra violet light shines certain colours for specific conditions) | Fungus: fluorescent |

| Skin biopsy | Psoriasis |

| Microscopy/fungal culture of skin lesion | Fungus |

| Skin patch tests to particular allergens | Review 2–4 days later for specific delayed contact allergies |

| Skin prick tests to particular allergens | Response to immediate contact allergies |

| Antinuclear antibody | Collagen disease, autoimmune disease |

| Liver function test | Hepatitis or hepatic disorder |

| X-ray on left and right hands | Rule out fractures, joint or bone abnormalities, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis |

| X-ray of spine | Osteoporosis |

| Bone densitometry (DEXA scanning) | Define diagnosis for osteoporosis |

Confirmed diagnosis

Prescribed medication

TABLE 11.24 DECISION TABLE FOR TREATMENT (ONCE DIAGNOSIS IS CONFIRMED)

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment for the presenting complaint and symptoms | Treatment for all associated symptoms | Treatment for mental, emotional, spiritual, constitutional, lifestyle issues and metaphysical considerations |

| TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY |

|

• Continue to use topical herbal preparations as necessary • Continue with lifestyle recommendations to improve skin quality and reduce dryness • Continue with physical treatment and lifestyle suggestions to reduce exposure to trigger factors and skin quality • Continue with physical treatment suggestions to help reduce hand pain and stiffness • Continue with herbal tonic and tea to reduce psoriasis symptoms and improve skin function • Continue with nutritional supplements to reduce psoriasis symptoms and improve skin NB: Margaret’s vitamin and mineral levels should be monitored to ensure they stay within acceptable limits; collaborative management of Margaret’s condition with her GP is important to ensure her treatment is appropriate and effective |

• Continue with recommendations to identify and manage dietary and environmental sensitivities

• Continue with dietary recommendations to include anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immune-modulating foods

• Continue with dietary recommendations to improve general health, liver and bowel function

• Continue with herbal tonic and tea to support liver and bowel function and modulate immune response

• Continue with nutritional supplements to improve general health, improve bowel health, reduce inflammation and improve skin quality

Treatment aims

• Decrease abnormal cell proliferation within the skin with the aim of normalising skin function [12, 41, 49], reducing dryness and improving skin quality [33].

• Reduce inflammatory processes within the skin [12, 41].

• Modulate the immune response. Psoriasis is a TH1-dominant condition [15].

• Enhance function of liver and bowel. Impaired liver function, bile deficiencies and bowel toxaemia are implicated in the development of psoriasis [12]. Altered bowel mucosa and inflammation are associated with psoriasis [50, 51].

• Improve protein digestion. Polyamines produced when breakdown of protein is inadequate are increased in psoriatics [12, 17]. Lowered skin and urinary levels of polyamines are associated with a clinical improvement in psoriasis [17].

• Support and protect Margaret’s cardiovascular system. Psoriatics have an increased risk of atherosclerosis [13, 41, 48].

• Support Margaret’s stress response. Stress can be a predisposing factor in psoriasis [14, 41].

• Where possible identify and remove dietary and environmental antigens, which may trigger or aggravate the condition [12, 15].

• Determine whether Margaret has a gluten intolerance and manage accordingly [12, 16].

Lifestyle alterations/considerations

• Stress-reduction techniques (e.g. meditation, tai chi, yoga) can be helpful by reducing the impact of stress on Margaret’s psoriasis [12, 14].

• The regular use of emollient creams or lotions can help keep Margaret’s skin supple and reduce dryness and itching [33].

• Margaret should avoid exposure to cigarette smoke [34].

• Margaret may benefit from exposure to sunlight [35].

• Margaret may benefit from counselling to help her deal with the stress of making a significant life change along with the stress her psoriasis is causing [28].

Dietary suggestions

• Reduce consumption of refined carbohydrates along with sugar, meat, saturated fat and alcohol and follow a low GI/GL diet to ensure her blood glucose levels are stable and stay within normal range [12, 42]. There is an association between psoriasis and abnormal blood-sugar levels [42].

• Margaret’s diet should be high in antioxidant-rich, nutrient-dense whole foods. Ensuring a high intake of antioxidants and essential nutrients is very important in psoriasis [12, 16, 48]. High consumption of fruit and vegetables is associated with a lower risk of psoriasis [14].

• Increase consumption of dietary fibre, particularly soluble fibre such as rice bran, oat bran, psyllium and linseeds. Soluble fibre can improve bowel flora and function [26].

• Increase consumption of foods containing omega-3 fatty acids [12, 16, 27]. Margaret may benefit from a period of fasting followed by a vegetarian diet [16].

• Include ½–1 tsp of turmeric in food each day [19]. Turmeric is anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulator, hepatoprotective and a cholagogue [18, 19].

• Encourage Margaret to include ginger in her diet. Ginger is anti-inflammatory [19, 40] and an antioxidant [18, 19] and immunomodulator [18, 19].

Physical treatment suggestions

• Acupuncture treatment may be beneficial. It may help improve the psoriasis [36] and reduce stress and anxiety [37].

• Hydrotherapy: brief full body baths in apple cider vinegar and salt baths can be beneficial for psoriasis [43]. Oatmeal baths for 20 minutes once or twice daily [44].

• Constitutional hydrotherapy [45, 46].

• Warm Epsom salt bath for 20 minutes to ease pain or tension [44].

• Hot foot bath to alleviate stress [47].

• Massage therapy may be beneficial in reducing Margaret’s anxiety and stress levels [39].

| HERB | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Topical application of turmeric can reduce the severity of active, untreated psoriasis [19] | |

TABLE 11.26 HERBAL FORMULA (1:2 LIQUID EXTRACTS)

| HERB | FORMULA | RATIONALE |

|---|---|---|

| 60 mL | Anti-inflammatory [18, 19]; immunomodulator [19]; depurative [18]; hepatoprotective [19]; antioxidant [18, 19]; cholagogue [18, 19]; improving liver function greatly benefits psoriasis [12] | |

| 40 mL | Adaptogen [18, 19]; mild sedative [18, 19]; anti-inflammatory [18, 19]; immunomodulator [18, 19]; traditionally used for improving stress adaptation [19]; traditional therapeutic use for psoriasis [18] | |

|

h |

70 mL | Anti-inflammatory [18, 23]; adrenal trophorestorative [18, 23]; uncured rehmannia is indicated for use in inflammatory disorders of the immune system, particularly skin and autoimmune disorders [23] |

| 30 mL | Anxiolytic [21, 19]; sedative [21, 19]; effective in anxiety and nervous restlessness [19, 24] |

Supply dose: 200 mL 5 mL 3–4 times daily

| Alternative to tea and coffee | ||

| HERB | FORMULA | RATIONALE |

| ½ part | Antipsoriatic [21, 22]; anti-inflammatory [22]; depurative [22]; mild cholagogue [21, 22]; antimicrobial [22]; laxative [21] | |

| 2 parts | Depurative [21, 22]; traditionally used for psoriasis [21, 22] | |

| 1 part | Alterative [20]; antirheumatic [20]; antiseptic [20]; antipruritic [21]; specific for psoriasis [21] | |

| 2 parts | Depurative [21, 22]; mild laxative [21, 22]; indicated for use in psoriasis [21] | |

Decoction: 1 tsp per cup – 1 cup 3 times daily

TABLE 11.28 NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS

| SUPPLEMENT AND DOSE | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

|

Providing 10, 000–12,000 mg EPA daily for at least 6 weeks [27], decreasing the dose to 6000 mg daily thereafter [19] |

Anti-inflammatory [16, 19, 25]; increases adhesion of probiotic bacteria to intestinal wall [25]; fish oil supplementation can reduce inflammatory processes associated with psoriasis [16]; supplementation of up to 10,000–12,000 mg EPA daily can significantly improve psoriasis [27] |

| Vitamin A deficiency is common in psoriasis [29] | |

|

Psoriatics can have increased serum copper:zinc ratio [30] Plasma zinc levels are lower in psoriatics than the general population [31]; psoriatics with extensive surface involvement have lower zinc levels than those with minimal involvement [31] |

|

| Supplement providing approx 800 IU Vitamin E [19, 25] and 200 mcg selenium [19, 25] daily in divided doses | Blood glutathione levels are lower in psoriatics [38] and supplementation with selenium and vitamin E can improve glutathione levels [38]; selenium deficiency is commonly found in psoriasis [32] |

| High-potency practitioner-strength multivitamin and mineral formula providing therapeutic doses of essential micronutrients and antioxidants [12, 16] | To provide broad-spectrum supplemental nutrients and antioxidants; people with psoriasis have increased oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant capacity [16, 48]; nutritional deficiencies are associated with psoriasis and supplemental nutrients and antioxidants may be beneficial [12, 16] |

[1] Talley N.J., O’Connor S. Pocket Clinical Examination, third edn. Australia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009.

[2] Kumar P., Clark C. Clinical Medicine, sixth edn. London: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

[3] Seller R.H. Differential Diagnosis of Common Complaints, fifth edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

[4] Jamison J. Differential Diagnosis for Primary Care, second edn. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006.

[5] Collins R.D. Differential Diagnosis in Primary Care, fourth edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

[6] Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. Skills for Communicating with Patients, second edn. Oxford: Radcliff Publishing; 2000.

[7] Neighbour R. The Inner Consultation; how to develop an effective and intuitive consulting style. Oxon: Radcliff Publishing; 2005.

[8] Lloyd M., Bor R. Communication Skills For Medicine, third edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009.

[9] Douglas G., Nicol F., Robertson C. Macleod’s Clinical Examination, twelfth edn. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, Edinburgh; 2009.

[10] Pagna K.D., Pagna T.J. Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test reference, third edn. USA: Mosby; 1997. (later edition)

[11] Peters D., Chaitow L., Harris G., Morrison S. Integrating Complementary Therapies in Primary Care. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002.

[12] Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T., Joiner-Bey H. The Clinicians Handbook of Natural Medicine, second edn. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

[13] Kural B.V., Orem A., Cimsit G., Yandi Y.E., Calapogula M. Evaluation of the atherogenic tendency of lipids and lipoprotein content and their relationships with oxidant–antioxidant system in patients with psoriasis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2003;328:71–82.

[14] Ortonne J.P. Aetiology and Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 1996;135(Suppl. 49):1–5.

[15] Wilsmann-Theis D., Hagemann T., Jordan J., Bieber T., Novak N. Facing psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: are there more similarities or more differences? European Journal of Dermatology. 2008;18(2):172–180.

[16] Wolters M. Diet and psoriasis: experimental data and clinical evidence. British Journal of Dermatology. 2005;153:706–714.

[17] Proctor M.S., Wilkinson D.I., Orenberg E.K., Farber E.M. Lowered Cutaneous and Urinary Levels of Polyamines With Clinical Improvement in Treated Psoriasis. Archives of Dermatology. 1979;115(8):945–949.

[18] Mills S., Bone K. Principles & Practice of Phytotherapy; Modern Herbal Medicine. Edinburgh: London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

[19] Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs & Natural Supplements: An evidence based guide, second edn. Sydney: Elsevier; 2007.

[20] Hoffman D. The New Holistic Herbal, second edn. Shaftesbury: Element Books Limited; 1996.

[21] British Herbal Medicine Association. British Herbal Pharmacopoeia. BHMA; 1983.

[22] S. Mills, K. Bone, The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety, Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, St Louis, 2004.

[23] K. Bone, Clinical Applications of Chinese and Ayurvedic Herbs: Monographs for the Western Herbal Practitioners, Phytotherapy Press, Warwick 1996.

[24] Akhondzadeh S., Naghavi H.R., Vazirian M., Shayeganpour A., Rashidi H., Khani M. Passionflower in the treatment of generalized anxiety: a pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial with oxazepam. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2001;26:363–367.

[25] Osiecki H. The Nutrient Bible, seventh edn. Eagle Farm: BioConcepts Publishing; 2008.

[26] Cummings J.H. Constipation, dietary fibre and the control of large bowel function. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1984;60:811–819.

[27] Maurice P.D., Allen B.R., Barkley A., Cockbill S.R., Stammers J., Bather P.C. The effects of dietary supplementation with fish oil in patients with psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 1988;117(5):599–606.

[28] Fortune D.G., Richards H.L., Kirby B., Bowcock S., Main C.J., Griffiths C.E. A cognitive-behavioural symptom management program as an adjunct in psoriasis therapy. British Journal of Dermatology. 2002;146(3):458–465.

[29] Majewski S., Janik P., Langner A., Glinska-Ferrenz M., Swietochowska B., Sawicki I. Decreased levels of vitamin A in serum of patients with psoriasis. Archives of Dermatological Research. 1989;280:499–501.

[30] Donadini A., Pazzaglia A., Desirello G., Minoia C., Colli M. Plasma levels of Zn Cu and Ni in healthy controls and psoriatic patients. Acta Vitamin Enzymol. 1980;1:9–16. (author’s translation)Article in Italian

[31] McMillan E.M., Rowe D. Plasma zinc in psoriasis: relation to surface area involvement. British Journal of Dermatology. 2003;108(3):301–305.

[32] Michaelsson G., Berne B., Carlmark B., Strand A. Selenium in whole blood and plasma is decreased in patients with moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venerol. 1989;69(1):29–34.

[33] Moden A.O. Role of Topical Emollients and Moisturizers in the Treatment of Dry Skin Barrier Disorders. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2003;4(11):771–788.

[34] Poikolainen K., Reunala T., Karvonen J. Smoking, alcohol and life events related to psoriasis among women. British Journal of Dermatology. 1994;130(4):473–477.

[35] Horio T. Skin Disorders that Improve by Exposure to Sunlight. Clinics in Dermatology. 1998;16:59–65.

[36] Liao S.J., Liao T.A. Acupuncture treatment for psoriasis: a retrospective case report. Acupuncture and Electrotherapeutics Research. 1992;17(3):195–208.

[37] Fassoulaki A., Paraskeva A., Patris K., Pourgiezi T., Kostopanagiotou G. Pressure Applied on the Extra 1 Acupuncture Point Reduces Bispectral Index Values and Stress in Volunteers. Anaesthesia & Analgesia. 2003;96:885–889.

[38] Juhlin L., Edqvist L.E., Ekman L.G., Luinghall K., Olsson M. Blood glutathione-peroxidase levels in skin diseases: effect of selenium and vitamin E treatment. Acta Derm Venerol. 1982;62(3):211–214.

[39] Moyer C.A., Rounds J., Hannum J.W. A Meta-Analysis of Massage Therapy Research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(1):3–18.

[40] Grzanna R., Lindmark L., Frondoza C.G. Ginger—An Herbal Medicinal Product with Broad Anti-Inflammatory Actions. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2005;8(2):125–132.

[41] Jamison J. Clinical Guide to Nutrition & Dietary Supplements in Disease Management. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

[42] Lynch P.J. Psoriasis and Blood-sugar Levels. Archives of Dermatology. 1967;95(3):255–258.

[43] Buchman D.D. The complete book of water healing. New York: Contemporary Books, McGraw-Hill Companies; 2001.

[44] Sinclair M. Modern Hydrotherapy for the Massage Therapist. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

[45] Boyle W., Saine A. Lectures in Naturopathic Hydrotherapy. Oregon: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1988.

[46] Chaitow L. Hydrotherapy, water therapy for health and beauty. Dorset: Element; 1999.

[47] Saeiki Y. The effect of foot-bath with or without the essential oil of lavender on the autonomic nervous system: a randomised trail. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2000;8:2–7.

[48] Banizor B., Orem A., Cimsit G., Yandi Y.E., Calapoglu M. Evaluation of the atherogenic tendency of lipids and lipoprotein content and their relationships with oxidant–antioxidant system in patients with psoriasis. Clinica Chimica Acta 328. 2003:71–82.

[49] Moller P., Knudsen L.E., Frentz G., Dybdahl M., Wallin H., Nexo B. Seasonal variation of DNA damage and repair in patients with non-melanoma skin cancer and referents with and without psoriasis. Mutation Research. 1998;407:25–34.

[50] Scarpa R., Manguso F., D’Arienzo A., D’Armiento F., Astarita C., Mazzacca G., et al. Microscopic inflammatory changes in colon of patients with both active psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis without bowel symptoms. Journal of Rheumatology. 2000;27(5):1241–1246.

[51] Ritchlin C. Psoriatic disease – from skin to bone. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(12):698–706.

[52] Schwartz R.A., Janusz C.A., Janniger C.K. Seborrheic dermatitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(1):125–130.

[53] Eming R., Hertl M. Autoimmune bullous disorders. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44(2):144–149.

[54] Roosterman D., Goerge T., Schneider S.W., Bunnett N.W., Steinhoff M. Neuronal control of skin function: the skin as a neuroimmunoendocrine organ. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(4):1309–1379.

[55] Svensson C.K., Cowen E.W., Gaspari A.A. Cutaneous drug reactions. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(3):357–379.

[56] Slominski A., Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(5):457–487.

[57] McLean W.H. Genetic disorders of palm skin and nail. J Anat. 2003;202(1):133–141.

[58] Jafferany M. Psychodermatology: a guide to understanding common psychocutaneous disorders. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;79(3):203–213.

[59] Cyr P.R., Dreher G.K. Neurotic excoriations. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1981–1984.

[60] Fawcett R.S., Linford S., Stulberg D.L. Nail abnormalities: clues to systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(6):1417–1424.

[61] Cahill J., Sinclair R. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(5):335–340.

[62] Schon W., Boehncke W.H. Psoriasis, N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1899–1912.

Acne

Case history

When you ask Elias about his diet he tells you he has either a can of energy drink or toast and coffee for breakfast. He usually buys his morning tea and lunch at the school canteen and has either a sausage roll or a pizza roll at recess and a burger or hot dog for lunch. He drinks either soft drink or fruit juice. Four days per week after school Elias works part time at a fast-food outlet. He usually eats something at work when he starts his shift and usually also eats something there for his evening meal as well. When he is at home Elias likes to have instant noodles or toasted cheese sandwiches. At least three nights per week Elias eats with his family but does not like eating vegetables so usually only has a small amount at the insistence of his mother. Further questioning reveals that Elias eats no fruit or whole grains, usually has one or two energy drinks daily and doesn’t drink any water.

| Analogy: Skin of the apple |

Where did the pimples first appear and how and where have they spread?

| Analogy: Flesh of the apple | Context: Put the presenting complaint into context to understand the disease |

| AREAS OF INVESTIGATION AND EXAMPLE QUESTIONS | CLIENT RESPONSES |

| Family health | |

| Is there a family history of acne? | Dad says he used to get it bad when he was growing up. |

| Recreational drug use | |

| No. | |

| Stress and neurological | Elias works part time and is also in Year 11. He is under stress because he wants to maintain school and work commitments. This has resulted in fatigue over the past 12 months. |

| Eating habits, energy and exercise | Elias has a poor diet with a high level of consumption of fast food and energy drinks, with little or no fruit, whole grains or water. Elias eats only small amounts of vegetables at the insistence of his mother. |

| Analogy: Core of the apple with the seed of ill health | Core: Holistic assessment to understand the client |

| AREAS OF INVESTIGATION AND EXAMPLE QUESTIONS | CLIENT RESPONSES |

| Emotional health | |

| Do you have any significant fears or anxieties at the moment? | I’m stressed about my skin. Also it is getting harder to keep up with my school and work commitments. |

| Environmental wellness | |

| How much time do you spend watching TV, on the computer or on your mobile phone? | A lot, I suppose, when I’m not studying or working. I talk to my friends on Facebook or MSN. |

| Stress release | |

| How do you manage your stress? | I don’t know, I suppose I talk to my friends and go out when I can. |

| Family and friends | |

| Do you spend much time with family and friends? | When I’m not at work I see my friends at school or when we go out. I see my family when I’m at home. |

| Action needed to heal | |

| What do you think you need to do to help improve your skin? | I don’t know, eat better and drink water I suppose. Maybe take some medicine too. |

TABLE 11.32 ELIAS’ SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS [2, 6, 9, 10]

| Pulse | 68 bpm |

| Blood pressure | 120/80 |

| Temperature | 37°C |

| Respiratory rate | 14 resp/min |

| Face | Open and closed comedones present over the whole face, upper back, neck and shoulders; evidence of cyst formation and some scarring; some comedones are red and inflamed |

| Body mass index | 21 – not often recorded as relevant because Elias is aged under 18 years |

| Urinalysis | No abnormality detected (NAD) |

Results of medical investigations

TABLE 11.33 UNLIKELY DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS [2, 7, 9, 10, 21, 51, 52]

| CONDITIONS AND CAUSES | WHY UNLIKELY |

|---|---|

| INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION | |

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis: affects those areas of the skin where there are sebaceous glands such as the face and scalp and occurs more with times of stress | Yellow scales; can be orange-red patches; borders are not well defined and have greasy scales; usually occurs in different typical locations such as centre of the chest, between the nose and lips, eyebrows, navel and groin; more common as an associated symptom of serious illness |

| Gram-negative folliculitis: characteristic bacterial infection with pustules and cysts on the face | Severe form of acne that is rare and can develop after long-term antibiotic use for acne vulgaris |

| Nodulocystic acne | Cysts that are inflammatory nodules and very severe |

| Acne rosacea: inflammatory disorder common on the face with pustules and papules on the nose, forehead and cheeks | More common in women; has associated symptoms of facial flushing; develops often in adult years over the age of 30 rather than in adolescence; rosacea has no comedones |

| ENDOCRINE/REPRODUCTIVE/SEXUAL HEALTH | |

| Acne conglobata: most severe form of acne, which is an inflammatory disease with blackheads, papules and abscesses; can be caused by steroid use or tumour-producing androgens; associated with testosterone and occurs mainly in men; appears on the face, neck and chest | Lesions fill with pus, crust over and fill again and can spread and remain a long time; sinus symptoms can be present; usually begins between 18 and 40 years of age; can cause severe scarring |

| Cushing’s syndrome: cause of acne | More common on the back and shoulders; no moon-shaped face, obesity, oedema, hypertension; urinalysis NAD |

| Diabetes: acne symptoms in insulin resistance | Urinalysis NAD |

| AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE | |

| Acne fulminans: immune disease with elevated testosterone levels most common in young adolescent males; fatigue can be a common symptom | Rare; would be associated with fever, muscle and bone pain; lack of appetite; begins with bone pain; will be severe acne that is nodulocystic; onset is abrupt |

|

Dermatitis herpetiformis: usually associated with bullae (fluid filled palpable mass); this condition is usually associated with gluten sensitive enteropathy, which can be asymptomatic Elias is consuming considerable amounts of gluten-containing foods; commonly occurs in early adulthood; more common to present on trunk of body |

|

TABLE 11.34 CONFIRMED DIAGNOSIS

| CONDITION | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Acne vulgaris | Common skin condition of this age group in adolescent males; comedones (black and white heads), papules, pustules and nodules; greasy skin, inflammation and scarring; areas of skin most affected with sebaceous glands |

Case analysis

| Not ruled out by tests/investigations already done [2, 9–11, 21, 24, 50–52] | ||

| CONDITIONS AND CAUSES | WHY POSSIBLE | WHY UNLIKELY |

| FAMILY HEALTH | ||

| Causal factor: Genetics: increase family history of acne | Acne – father has a history of acne | |

| ALLERGIES AND IRRITANTS | ||

| Causal factor: Food intolerances/allergies | Fatigue, skin break outs, constipation | Need to assess dietary habits more clearly |

| RECREATIONAL DRUG USE | ||

| Causal factor: Drugs: amphetamines, cannabis, cigarette smoking, alcohol | Acne, constipation, episodes of fatigue, spending a lot of time out of the family home | Eyes are not red, no signs of restlessness, still active with everyday routine; need to ascertain if Elias uses recreational drugs |

| OBSTRUCTION | ||

| Causal factor: Intestinal obstruction: e.g. faecal impaction | Constipation | No abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting reported |

| FUNCTIONAL DISEASE | ||

| Causal factor: Functional constipation | Acne and bowel motion only a couple of times a week; not drinking enough water, high caffeine intake; stress | Need to check if more than 1 in 4 bowel motions is lumpy and hard, and causes strain, a feeling of incomplete evacuation or blockage; need to check if manual help is needed to facilitate a bowel motion passing; if Elias has fewer than 3 evacuations a week |

| DEGENERATIVE AND DEFICIENCY | ||

| Causal factor: Organic fatigue: no major physical abnormalities | Tired, sleep disturbances | Shorter duration than functional fatigue; need to determine if the feeling of fatigue worsens during the day |

| Anaemia | Fatigue; diet may be low in nutrients | Assess iron and B12-rich food intake |

| Sunlight | Can exacerbate acne | Can help acne [9]; UVB and UVA phototherapy have been used to treat inflammation of acne [2] |

| INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION | ||

| Causal factor: Hygiene | Excess oil and grease can clog pores | Studies are inconclusive that excess washing helps acne and it may exacerbate in some circumstances [15, 16] |

| SUPPLEMENTS AND SIDE EFFECTS OF MEDICATION OR DRUGS | ||

| Causal factor: Medications: lithium, androgens, corticosteroid therapy | Acne | Corticosteroid-induced acne lesions will often be on the back and shoulders (rather than the face); lesions are usually pustules at the same stage of development with no comedones present; no Cushing’s symptoms present |

| ENDOCRINE/REPRODUCTIVE | ||

| Causal factor: Hormonal balance: increase androgens in adolescence | Elias is of the gender and age group that most commonly has acne | |

| STRESS AND NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE | ||

| Depression | Many adolescents with acne show signs of depression and low self-esteem [2] | Need to explore the level of fatigue and intensity of emotions, interest in daily activities and social network |

| Causal factor: Physiologic fatigue: diagnostic studies within normal limits; symptoms present for less than 14 days and not usually associated with changes in self-esteem, social difficulties or overall mood | Can be caused by depression, caffeine, alcohol, excess sleep or intense emotions | Need to question Elias more on self-perception and duration of fatigue |

| Causal factor: Functional fatigue – (depression): tiredness that lasts several months | May be eating junk food as comfort food during depression | Need to determine if the feeling of fatigue improves during the day |

| Anxiety | Excess sympathetic nervous system response may affect stress and skin lwevels [22] | Speech not fast, no fast pulse rate or no significant weight loss mentioned; lack of sleep not mentioned, not restless or fidgety, no sweating |

| Causal factor: Emotional stress: affects androgen levels [22] | Acne [15, 16] | |

| EATING HABITS AND ENERGY | ||

| Causal factor: Dietary factors: increased carbohydrates and refined sugars increase insulin and then insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) | Acne, constipation; excess sugar may increase androgen production by influencing SHBG [11–14, 44] | Studies have shown inconclusive evidence that dietary factors affect acne [15, 16] |

| Causal factor: Dairy foods: due to insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) in dairy cows (journals below) | Acne, constipation [11, 44] | |

| Causal factor: Exercise | Lack of exercise can exacerbate acne if extreme | Exercise can reduce insulin resistance [45] and stress hormones [46] to improve acne |

| Causal factor: Dehydration | Lack of water, constipation, fatigue | |

TABLE 11.36 DECISION TABLE FOR TREATMENT PRIOR TO REFERRAL

• Dietary recommendations to improve diet and intake of essential nutrients specific for skin health as well as for general good health

• Dietary recommendations to cut out refined carbohydrates, energy drinks, soft drinks, and processed, fried and fatty foods

• Recommendation to identify food allergies or sensitivities and manage accordingly

• Skin care recommendations to gently cleanse skin and drain comedones and avoid applying topical preparations, which may clog pores and aggravate acne

• Recommendation for Elias to give his skin limited exposure to sunlight

NB: Caution should be exercised that sun exposure is not excessive

• Recommendation for Elias to exercise regularly to help improve glycaemic control and reduce the action of insulin on sebum production

• Herbal tea with cholagogue, detoxifying and mild laxative action to improve bowel function and detoxification

• Supplemental nutrients to improve status of essential nutrients resulting from Elias’ poor diet

TABLE 11.37 DECISION TABLE FOR REFERRAL

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Referral for presenting complaint | Referral for all associated physical, dietary and lifestyle concerns | Referral for contributing emotional, mental, spiritual, metaphysical, lifestyle and constitutional factors |

| REFERRAL FLAGS | REFERRAL FLAGS | REFERRAL FLAGS |

| ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE | ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE | ISSUES OF SIGNIFICANCE |

| Nil | ||

| REFERRAL | REFERRAL | REFERRAL |

TABLE 11.38 FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS THAT MAY BE NECESSARY [2, 6, 9, 10]

| TEST/INVESTIGATION | REASON FOR TEST/INVESTIGATION |

|---|---|

| FIRST-LINE MEDICAL INVESTIGATIONS: | |

| Full blood count | Anaemia, inflammation, allergies |

| Fasting blood glucose test | Diabetes or insulin sensitivity |

| Blood electrolytes | Dehydration |

| Skin examination and assessment | Specialist dermatology assessment for severity of acne, dehydration |

| Abdominal inspection: guarding, rebound tenderness, palpation, abnormal pulsations (auscultation) | Constipation or obstruction |

| Diet diary | Assess food intake over a period of time |

| Skin diary | Assess any changes in acne over a period of time or patterns/triggers |

| IF NECESSARY: | |

| Serum cortisol | Cushing’s syndrome, adrenal response |

| Abdominal x-ray | Constipation |

Confirmed diagnosis

Elias and acne vulgaris with physiologic fatigue

Elias is a young man of 16 who has come to the clinic with his parents, Dorota and Henry, for help to clear acne on his face, back and chest. Elias has experienced acne since he was 14 and the condition is worsening. Recently he was diagnosed with acne during a routine visit to his medical practitioner and was offered antibiotic treatment. Dorota wanted to try alternative treatment approaches such as diet and lifestyle changes before the prescribed medication. Their doctor referred Elias to the complementary medicine clinic to collaboratively assist clearing the condition.

Prescribed medication [21, 53]

If diet and lifestyle changes are not helping:

TABLE 11.39 DECISION TABLE FOR TREATMENT (ONCE DIAGNOSIS IS CONFIRMED)

| COMPLAINT | CONTEXT | CORE |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment for the presenting complaint and symptoms | Treatment for all associated symptoms | Treatment for mental, emotional, spiritual, constitutional, lifestyle issues and metaphysical considerations |

| TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY | TREATMENT PRIORITY |

|

• Continue with dietary recommendations to reduce excessive sebum production • Continue with lifestyle recommendations for skin care and topical application of essential oils • Continue with herbal skin wash NB: Elias’ serum vitamin A levels should be monitored to avoid toxicity; vitamin A supplement should be stopped if Elias takes prescribed retinoid medication |

• Continue with dietary recommendations to improve intake of essential nutrients and eliminate refined carbohydrates, fried and fatty foods, processed foods, energy drinks and sugar

• Manage food allergies or sensitivities

• Continue with skin care recommendations and limited sunlight exposure

• Continue with exercise for general health and glycaemic control

• Continue with herbal tea to improve bowel function and detoxification

• Continue with supplemental nutrients at least until Elias’ diet improves enough to be providing sufficient levels of essential nutrients

Treatment aims

• Unblock sebaceous glands [18–20].