Chapter 1 Integument problems

1.1 Introduction

Many lesions of skin or subcutaneous tissue are easily recognised and a diagnosis can be made virtually on inspection alone. Lipomas, ‘sebaceous’ cysts and ganglia are very common and usually have classic diagnostic features. Subcutaneous swellings are thus commonly benign — malignancies are rare but important to recognise. Many focal surface lesions are also benign and easily diagnosed; however, skin cancers are also common and any hint of malignancy requires biopsy for a certain diagnosis.

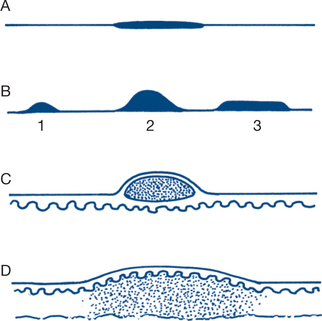

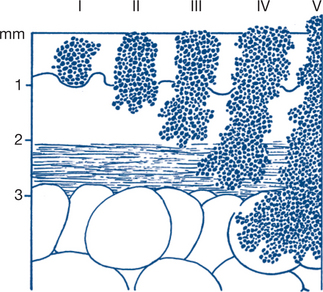

Focal skin lesions are divided morphologically into four main types: macules; papules or nodules; vesicles or pustules and wheals (Fig 1.1).

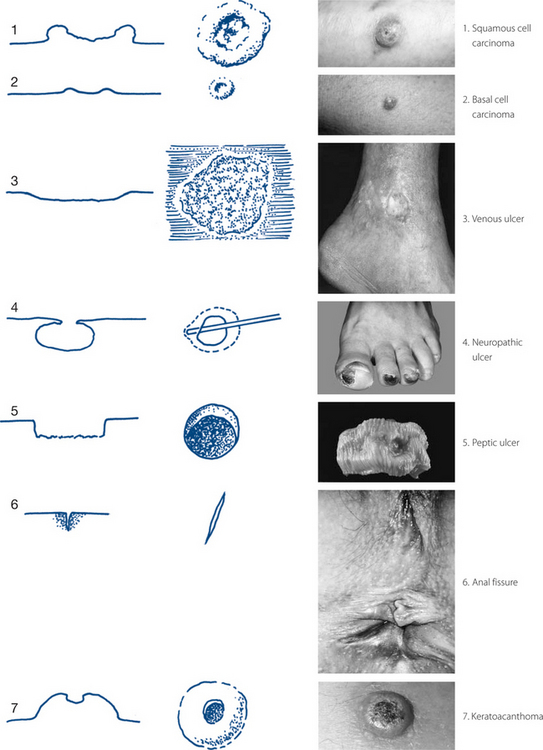

A macule is a localised surface change in skin colour without bulk or substance. It is important to note whether the colour change is permanent or blanches on compression. A lightly pigmented brown or tan macule is called a lentigo or freckle. A papule is a small solid projection above the skin surface; a larger papule is called a nodule. A flattened nodule is described as a plaque. Vesicles are elevated fluid-containing lesions: When large they are called bullae or blisters and when they contain pus, pustules. Acne (Greek — a facial eruption) comprises multiple small pustules, which if embedded are described as comedoform. Milia are tiny embedded cutaneous plaques due to keratinous retention foci; they are most common on the facial skin. Wheals are white, raised lesions of localised dermal oedema without blistering. Widespread wheals are often called urticaria, an atopic (allergic) reaction. If the skin is broken the lesion is an ulcer. Distinct morphological types of ulcer are also described (Fig 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Types of epithelial ulceration

Sources: Squamous cell carcinoma: From Rakel 2007; Basal cell carcinoma: From Rakel 2007; Venous ulcer: From Bolognia et al 2007; Neuropathic ulcer: From Bolognia et al 2007; Peptic ulcer: Courtesy of Robin Foss, University of Florida; Anal fissure: Courtesy of Gershon Effron, Sinai Hospital of Baltimore; Keratoacanthoma: From Habif 2003.

The clinical history of a lump or ulcer

1 Onset and duration

It is important always to ask the patient’s opinion of the cause of the lesion or of any incident associated with its onset. The patient may relate the lesion to an occupation, a drug or an injury. The length of history gives some idea of prognostic significance. The onset of skin lesions may be related by the patient to a triggering factor such as an insect bite. A previous history of repeated trauma may be important in pyogenic granuloma and in implantation dermoid cyst. A sudden change in the characteristics of a pre-existing mole suggests melanoma. Other skin lesions may be induced by local or systemic drug treatment.

2 Change and progression

The rate of progression helps to distinguish between benign and malignant conditions (Table 1.1). A skin lesion that progresses to a significant lump within a few days suggests infection (e.g. pyogenic granuloma); in a few weeks, hyperplasia (e.g. keratoacanthoma); or over several months, malignancy (e.g. basal and squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma). A pigmented skin lump that has not changed over several years suggests a benign mole. Most subcutaneous lumps are benign and very slowly progressive. ‘Sebaceous’ or epidermoid cysts are prone to infection, partial resolution and recurrence. Sometimes a ganglion may rupture after trauma and disappear, to return later. Abdominal wall hernias may appear suddenly after a strain and slowly progress; they are usually reducible and reappear on standing. Basal cell carcinomas may appear to heal in part of their circumference but are usually inexorably progressive.

| Length of history | Clinical appearance | |

|---|---|---|

| Basal cell carcinoma | Months to years | Pearly nodule |

| Central crusting and ulceration | ||

| Rolled or beaded, telangiectatic edge | ||

| Any site, especially head and neck | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Months | Indurated, ulcerating, raised nodule, everted friable edge |

| Contact bleeding | ||

| Sun-exposed surfaces | ||

| Keratoacanthoma | Weeks | Rapidly growing |

| Dome shaped | ||

| Volcanic apical ulceration | ||

| Sun-exposed surfaces | ||

| Pyogenic granuloma | Days or weeks | Small, soft, cherry red lesions |

| Contact bleeding | ||

| Common on mucocutaneous surfaces |

4 Multiplicity

The history should be completed by a general systems review and the family, social, occupational and allergic history. This is particularly important for skin ulcers where systemic diseases such as alcoholism, rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes are important factors to consider, both in aetiology and in treatment. Diabetes mellitus is frequently a factor in delayed healing of ulcers. Some conditions have a particular geographical predisposition such as the ‘Bairnsdale ulcer’ for which the aetiology is an atypical mycobacterium of limited geographical range.

The physical examination of a lump or ulcer

An abnormality in a bilateral structure should be compared and contrasted with its normal side. Assessment of a lump traditionally follows a sequential analysis of its characteristics (Box 1.1). Although not all the features are applicable to all lumps, it is essential to follow an ordered sequence when characterising any lump. The most important features are the site (which should be defined anatomically in all dimensions) and the physical characteristics, including relationships of the lump to its surroundings.

3 Shape and surroundings

A smoothly regular spherical lump strongly suggests a cyst. Most solid lumps have slight or prominent irregularities of shape, even when generally spherical or oval. To describe a lump’s shape as spherical implies that it has been assessed totally in three dimensions. This is only possible with very mobile lumps or when an adjunct to examination such as an ultrasound is available. More often only a portion of the circumference of the lump can be felt and its roundness implied from this assessment. Cystic liquid collections are common in skin and subcutaneous tissues and include ‘sebaceous’ cysts and bursae.

Ulcers can be regular or irregular in shape and their edges can also be described as serpiginous, sloping, everted, rolled, overhanging or punched-out (Fig 1.2). Brown pigmentation, a desquamative rash and induration of skin and subcutaneous tissues around an ulcer suggest venous insufficiency. Redness, heat, oedema and cellulitis indicate active spreading infection.

5 Contour

6 Consistency

Apart from these four grades, familiar analogies can help to describe size and consistency (e.g. golf ball or tennis ball size and feel). A diagnostic description (solid or cystic lump) combines the clinical features of shape, contour, consistency and other aspects.

9 Transillumination

Bursae, hydroceles and epididymal cysts are common transilluminable lumps. Ganglia involving tendon sheaths usually transilluminate. Firmer, deeper ganglia near joints usually do not. ‘Sebaceous’ cysts do not transilluminate because of their pultaceous contents and thick walls. Lipomas are not usually transilluminable and never brilliantly so. Transillumination of a focal lump must be differentiated from the normal luminescence of subcutaneous tissue around the beam of a torch.

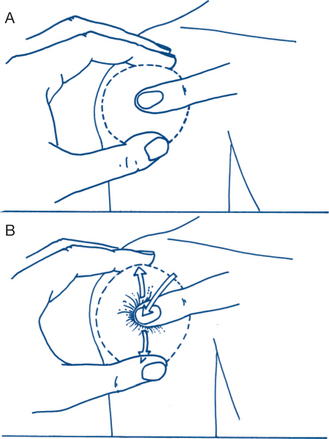

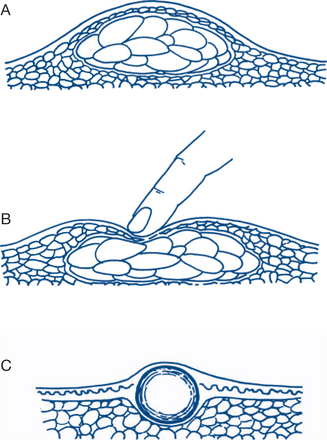

10 Fluctuation and percussion

Fluctuation is tested (preferably in two planes at right angles to each other) with a compressing and a testing finger. The lump must be fixed to ensure that it has not been itself moved by the compressing finger. The transmitted impulse of fluid is appreciated by the second, testing finger (Fig 1.3). A variation of this test is the demonstration of a fluid thrill in ascites. With some lumps, three fingers can be used conveniently. Two fingers of one hand on opposite sides of the lump control it and both test for transmission of an impulse when the index finger of the other hand compresses the lump, or both compress the lump while the index finger of the other hand tests for fluctuation.

11 Fixity

Mobility on swallowing is an important sign for neck swellings: structures normally related to the trachea or larynx exhibit this sign, which is characteristic of a goitre (Ch 2.15). Movement on inspiration occurs when intraperitoneal lumps are related to the under surface of the diaphragm (liver, spleen).

1.2 Focal skin lesions

Most focal skin lesions will be manifestly benign longstanding lesions of congenital or acquired origin that have caused the patient no problem and require no treatment. Benign skin lesions include a large number of congenital blemishes, moles, malformations and hamartomas. Benign neoplasms, localised infections and miscellaneous causes are also common (Fig 1.4). An important group of lesions are dysplastic and premalignant. Accurate diagnosis of this latter group is extremely important, as early surgical treatment of suspicious skin lesions is curative for most forms of skin malignancy. Screening programs and self-examination in high-risk populations have been employed but vary in effectively diagnosing early lesions. Repeated practice at assessing common skin lesions rapidly improves diagnostic skills. Accurate diagnosis relies first on a careful history and examination.

Focal skin disorders can be assessed on clinical grounds into:

Pigmented lesions (naevi) form a distinct category within each of these two groups.

Clearly benign lesions

Benign skin lesions will usually have been present from birth or for many years without change. In children and adolescents, congenital moles and vascular malformations are common, as are freckles and infective warts; skin malignancies are rarely seen (Box 1.2). In adulthood, degenerative and other specific lesions occur with increasing frequency in patients over the age of 40 years (Box 1.3); differentiation of benign lesions from cancers becomes increasingly important. Lesions are defined as macules or nodules. Common macules are the port wine stain, café au lait spots (neurofibromatosis), some junctional naevi and freckles. Freckles are common in children and adolescents. In older patients senile freckling of the skin is common, as are spider naevi and senile purpura. Common benign nodules include pigmented moles and angiomas. Verrucous lesions are also common in children and adults. Benign skin tags and keratoses are seen with increasing frequency in older patients. Benign traumatised lesions may ulcerate. In adults this always invokes suspicion of malignancy; in children benign ulcerated or infective lesions are relatively common. Skin vesicles occur with herpetic infections, eczema and impetigo.

Clinical features, diagnostic and treatment plans

Children

Intradermal, junctional and compound naevus

Intradermal naevus is the most common benign mole, deriving its name from the fact that the pigment cells lie entirely within the dermis (Fig 1.5). The macroscopic appearance varies considerably: from a soft flattened pale brown or flesh-coloured nodule or macule, to a deep brown warty excrescence. The edge is usually well defined. Many contain hair, which is a helpful diagnostic point — hairy moles are virtually always intradermal and benign. Intradermal naevi occur all over the body skin and are usually present from birth but are rare on the palms or finger-tips. They vary in size from a few millimetres to large lesions several centimetres across. They are biologically conservative, wholly benign lesions, throughout life.

Adults

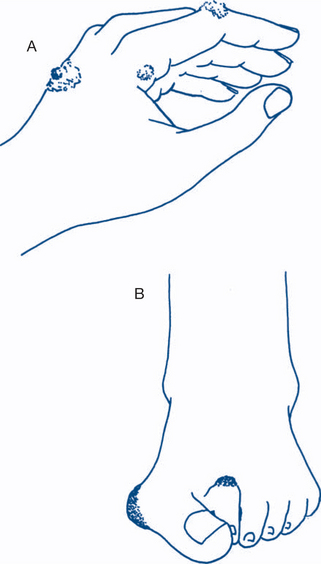

Callosity (callus)

These are more common in adults and are diffuse or localised areas of thickened hyperkeratinised skin in response to excessive wear. The calloused hands of farmers and manual labourers contrast with those of sedentary workers. Calluses occur maximally over pressure points and so are prominent on the volar skin of hands and fingers. They are usually symptomless and of no clinical significance. Corns are calluses of the feet and toes and tend to be more localised and to extend more deeply when on weight-bearing skin. They are commonly sited over bony prominences or deformities (bunions, claw or hammer toes, metatarsal heads) and can then become symptomatic and painful under stresses of weight-bearing and constriction by shoes. Treatment is of the causal deformity.

Senile haemangioma (Campbell de Morgan spot, cherry angioma, cherry spot)

These bright red, discrete skin nodules become increasingly common in the later years of life and present usually as multiple lesions of the back and trunk on elderly patients, more commonly in males. They do not blanch on pressure, once seen are instantly diagnosable and have no clinical significance.

‘Suspicious’ Lesions

Clinical features and diagnosis

1 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

These commonly occur on the face but may present at less typical sites. Basal cell tumours are locally malignant but do not metastasise to lymph nodes or via the bloodstream. They can present in various ways (Box 1.4). The usual presentation is as a raised pink nodule with a characteristically translucent pearly sheen and with fine telangiectasis visible through the stretched skin surface. Later the nodule proceeds to central shallow ulceration with a rolled edge. The lesions grow slowly but irrevocably and neglected ones can cause gross local infiltration and destruction of tissue — the ‘rodent’ ulcer. Occasionally, multiple BCC occur with a familial and inherited pattern.

2 Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

The SCC starts as a hyperkeratotic warty plaque or nodule, progressing to a typical malignant ulcer with a raised everted edge. Contact bleeding is more common than with BCC. Spread to regional lymph nodes occurs and may occasionally be the presenting symptom with a small or occult primary. Blood-borne metastasis to lungs and other sites occurs in aggressive varieties such as those in immunosuppressed patients. Histologically, masses or strands of malignant cells extend into the dermis and deeper tissues. Varying degrees of differentiation are seen. Keratinised nests or ‘pearls’ are common histological features.

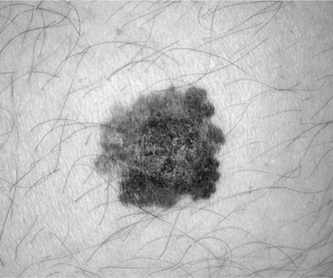

5 Malignant melanoma

This is the most malignant of all skin tumours. It occurs throughout adult life. Melanomas are particularly prevalent in fair-skinned populations in tropical climates. They are more common in females than in males and their geographical frequency varies widely. Melanomas are rare in black races, except in depigmented areas of skin. Any brown or black mole that shows increase in size, irritation, bleeding, nodularity or ulceration should arouse suspicion and should be excised (Fig 1.6).

Figure 1.6 The ABCDE assessment aids in the identification of skin lesions suspicious of melanoma

From Townsend et al, 2007

Hutchinson’s melanotic freckle (lentigo maligna melanoma). This presents initially as a dark brown macular stain on the face of older patients, particularly elderly women. Histology shows junctional activity without invasion and the lesions can remain stationary for years. Spreading growth continues laterally in an irregular fashion, giving a distinct but irregular edge and a typically variegated pigmented appearance of the surface. The lesion will invariably progress ultimately to malignant change and the edge of the malignancy can be difficult to define.

Treatment plans

Focal lesions that are suspicious of malignancy require surgical excision. An ulcerated lesion automatically induces suspicion. Lesions can usually be sorted clinically into those in which the diagnosis of BCC, SCC, keratoacanthoma or melanoma is fairly clear-cut and those in which the diagnosis is equivocal. Many diagnostic mimics exist (Table 1.2). Surgical excision provides a tissue diagnosis and for most lesions is curative with one procedure. Massive and cosmetically disfiguring excisions should not be performed.

| Malignant lesion | Common mimics |

|---|---|

| Basal cell carcinoma | ‘Sebaceous’ cysts |

| Acne | |

| Psoriasis | |

| Dermatofibroma | |

| Other focal infective lesions | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Solar keratosis |

| Bowen’s disease | |

| Keratoacanthoma | |

| Infected ‘sebaceous’ cyst | |

| Pilomatrixoma | |

| Pyogenic granuloma | |

| Dermatitis artefacta | |

| Any focal ulcer | |

| Malignant melanoma | Benign pigmented naevus |

| Dermatofibroma | |

| Pigmented BCC | |

| Seborrhoeic keratosis | |

| Amelanotic melanoma | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Pyogenic granuloma | |

| Kaposi sarcoma | Benign haemangioma |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | Dermatofibroma |

| Merkel cell tumour | BCC, haemangioma |

3 Keratoacanthoma

Although keratoacanthoma may mimic an SCC, it will resolve and can be managed by careful observation and excision only if the clinical course is unexpected. Multiple and recurrent lesions may be managed with medication.

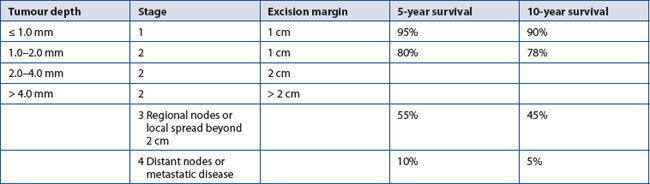

5 Melanoma

Treatment of all suspicious lesions (Box 1.5) is by surgical excision and confirmation of diagnosis by histology. Excision should be adequate in width and depth. It is difficult to define precisely the requirements for adequate excision; for benign skin lesions 1–2 mm is adequate. Recommended margins relate to the depth of the tumour. Where adequate excision and primary closure is not cosmetically acceptable, plastic and reconstructive options should be considered in surgical planning.

Lymph node involvement considerably worsens prognosis at any stage. The natural history of recurrences or metastasis is very variable. Late metastases — 10 years or more after the initial presentation — are quite common, so follow-up should be prolonged and meticulous, looking for locoregional and distant metastatic disease and new primary lesions. Therapy for recurrent melanoma may include excision of metastatic disease (Table 1.3).

7 Other malignant or infective skin lesions

Infected or traumatised benign lesions. Infection and recurrent trauma can mimic malignant change. Infected ‘sebaceous’ cysts (Ch 1.3) can mimic squamous or basal cell carcinoma. Other benign lesions mimicking malignancies include seborrhoeic keratosis, dermatofibroma and pilomatrixoma. Pigmented BCC and benign moles can each mimic malignant melanoma.

Pigmented skin lesions

Diagnostic and therapeutic plans

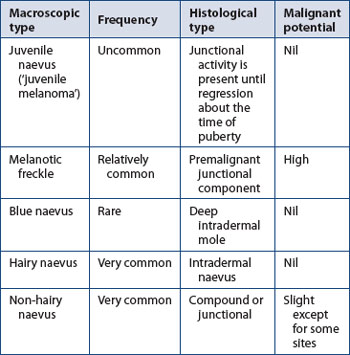

Many adult lesions will be longstanding and also clearly benign. Different types of benign pigmented moles are summarised in Table 1.4.

Indications for excision of pigmented skin lesions are outlined in Box 1.6. Ultimate diagnosis rests on histological examination of the excised specimen. Biopsy is usually best done by total excision rather than incision. Frozen section diagnosis can be helpful in planning the extent of operative excision for equivocal lesions. About 50% of malignant melanomas arise in a pre-existing dysplastic naevus.

Box 1.6

Pigmented skin lesions — indications for excision

Suspicion of malignant melanoma

Prophylactic excision of premalignant lesions

‘dysplastic’ naevus: particularly large junctional and compound naevi and those on certain sites (palms, genitals, soles)

‘dysplastic’ naevus: particularly large junctional and compound naevi and those on certain sites (palms, genitals, soles)Repeated trauma to benign lesions (intradermal naevus in beard area)

1.3 Subcutaneous lumps

Clinical features and treatment plan

1 Lipoma

Subcutaneous lipomas present as very slow-growing, soft, painless, subcutaneous swellings. The surface contour is classically lobulated. In areas of lax skin they are freely mobile in the subcutaneous layer and consequently tend to slip from beneath the palpating finger (Fig 1.8). Mobility and freedom from attachment to the skin, although classic and helpful signs, are not invariable. In regions such as the back of the neck, where the skin is thick and the underlying subcutaneous fat is closely attached to it, a large lipoma just beneath the skin tends to be firmer and flatter. The lipoma then cannot be moved independently of the surface skin nor can the skin be pinched or pushed away from the lump without skin dimpling. Differentiation from sebaceous cyst becomes more difficult in these circumstances but the irregular shape and lobulated contour of the lipoma, as distinct from the spherical shape and smooth surface of the cyst, usually are unequivocal contrasts. In areas of very lax skin, lipomas can become pedunculated but this more commonly occurs with cutaneous neurofibromas. Lipomas are often fluctuant. Firmer or deeper ones and those beneath thick overlying skin are not fluctuant. Lipomas do not usually transilluminate.

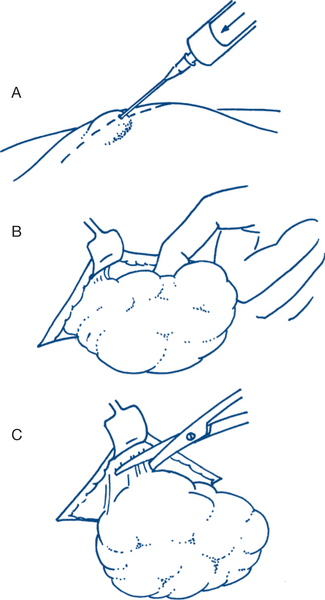

Treating lipomas often consists of just reassuring the patient of the benign nature of the lump. Removal, if required, is usually simple. Even large ones can be shelled out completely from within their soft capsules through quite small incisions (Fig 1.9). Recurrence does not occur after removal of the whole lesion. Incision is preferably along lines of skin cleavage (Langer’s lines).

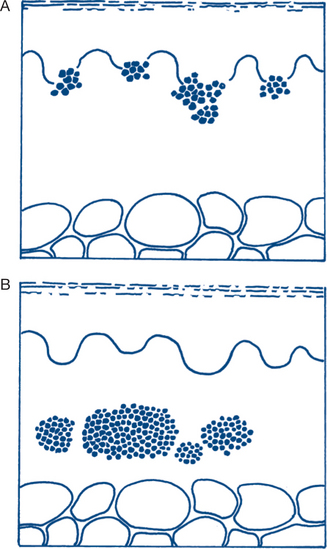

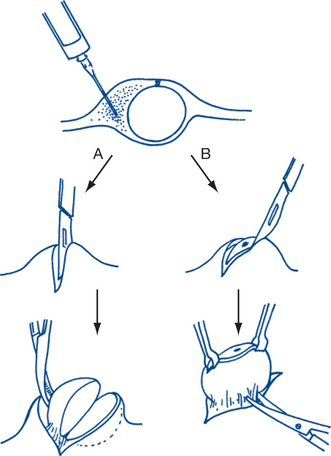

2 ‘Sebaceous’ cyst

(a) ‘Sebaceous’ cysts arise from the skin and its appendages and are thus primarily cutaneous swellings — they move with and not apart from the skin. They are thus always attached to the skin at their summit, even when very large and with the major part of their bulk expanded into the soft tissues beneath the skin. Even so, they remain ensheathed by a dermal layer (Fig 1.8). The presence of a punctum (not always present) makes their epidermal origin even more obvious — it is usually at the summit but may be eccentric and can be missed unless sought for with care.

Complications of keratinous cysts are common:

Infection and abscess formation have already been mentioned. Infected cysts can be very malodorous. Although spontaneous resolution with destruction of the cyst may occasionally occur, simple incision or spontaneous drainage of pus is more usually followed by recurrence of the lesion. Cure requires excision of the cyst, including its wall. A large infected sebaceous cyst of the scalp is known as Cock’s peculiar tumour. This can mimic a squamous cell carcinoma of skin (Ch 1.2) and highlights the importance of always confirming the diagnosis histologically. Another and more serious error is to mistake an underlying bony tumour of the calvarium for a sebaceous cyst. Cysts lie within the skin of the scalp above the epicranial aponeurosis and are always mobile over the underlying bone; however, the scalp is stretched quite tightly over the skull and this sign can be misinterpreted by the inexperienced or careless observer.

Treatment. Symptomatic ‘sebaceous’ cysts need to be excised in toto, which can be done under local anaesthesia. The simplest technique is to bisect the cyst cleanly and avulse each half from within using a haemostat (Fig 1.10). Bleeding is usually minimal. Complicated cysts need formal excision. Histological confirmation of the diagnosis is always mandatory.

3 Ganglion

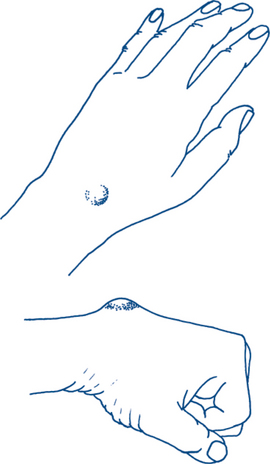

Ganglia present as more deeply placed subcutaneous lumps around joints or tendon sheaths. They are seen very commonly throughout adult life; they may be precipitated by work involving repetitive movement or associated with degenerative arthritis of the underlying joint. Associated arthritis may be the cause of symptoms, and treatment of the more obvious ganglion will not then effect a cure. Common sites for ganglia are wrists, fingers and feet. Their consistency and size are variable and may change with movement of the corresponding joint or tendon.

They present either as small localised swellings or as diffuse tendon sheath enlargements.

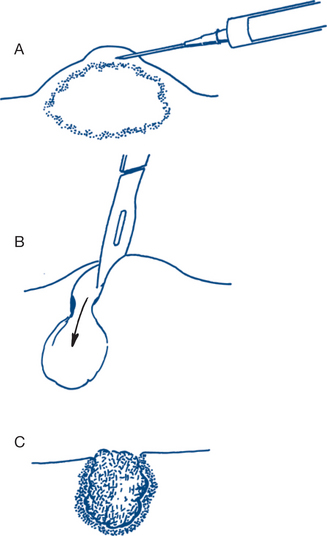

Localised swellings. A tense focal lump due to herniation or cystic degeneration of the joint capsule or tendon sheath is the most common form of ganglion. A very common presentation is a small (1–2 cm), tense, firm or hard subcutaneous swelling on the dorsum of the wrist joint towards its radial side and made more prominent by hyperflexion of the joint (Fig 1.11). The lump is immobile, fixed to the deep tissues and not attached to skin. Most will be too firm to elicit fluctuation and are not usually transilluminable. These ganglia may be unilocular or multilocular and contain a clear glairy synovial-like fluid. The natural history varies considerably. Many or most are symptomless in themselves and grow very slowly or remain static. Spontaneous resolution sometimes occurs; this may be accelerated by local pressure causing apparent rupture and dissipation. Recurrence is frequent.

Figure 1.11 Ganglion on the dorsum of the wrist joint is made more prominent by hyperflexion of the joint

Synovial (mucous) cyst of the finger is another common type of localised ganglion. This lesion presents as a subcutaneous cystic nodule over the dorsum of the terminal phalanx just distal to the interphalangeal joint. The tense fluctuant subcutaneous cyst is in close proximity to the nail bed and often causes local deformity of nail growth. Treatment is initially conservative (many resolve spontaneously). Local excision is required for persisting lesions; aspiration and local steroid injection may be tried first.

A mucous cyst that is completely subungual can be confused with melanoma.

5 ‘Dermoid’ cysts

Traumatic (implantation) dermoid cyst. This is a common lesion of the fingers or palm in adults. It is due to implantation of epithelial elements, usually from repeated occupational trauma (e.g. a seamstress or wire worker) or related to a surgical incision. It presents as a small (<1 cm) firm spherical nodule just beneath the skin surface and attached to it and is often painful and tender. Usually an overlying puncture wound or scar is apparent. Symptomatic lumps need surgical excision.

1.4 Cutaneous and subcutaneous infections

Pathology

Surgical infection develops in overlapping phases:

Cellulitis. Early spreading subcutaneous infection is the most common manifestation.

Clinical features

Systemic toxicity (septicaemia), due to bacteraemia and circulating endotoxins and tissue breakdown products, is manifest by symptoms of lethargy, weakness, restlessness, delirium, shivering and chills, as well as signs of fever, tachycardia and hypotension. Metastatic abscess formation with specific signs related to the organ involved may manifest later.

Diagnosis and treatment plans

General principles

General principles of treatment (Box 1.7) are determined by the three main aetiological factors:

Box 1.7

The general principles of the treatment of surgical infection

1 The primary site of infection

The presence of tension and impending tissue necrosis is suggested by persistent throbbing pain and systemic toxicity, and is an indication for urgent surgical decompression — even in the absence of signs of pus. Fluctuation is frequently a late sign of abscess formation and drainage should not be delayed until this sign is present (Fig 1.12). Superficial infected ulcers or infected wounds are best dressed by adequate drainage and by moist porous dressings. After drainage, later secondary closure by suture or by skin grafting may be required to reduce the length of convalescence. The local region should initially be rested, immobilised and elevated to minimise oedema. Physiotherapy is commenced once there is evidence of resolution of the infection and is an important component in final rehabilitation.

2 The infectious agent

Heavy bacterial contamination increases the susceptibility to infection. Wounds sustained in a dirty environment and in patients with dermatological conditions associated with a heavy load of bacteria, such as impetigo, are more likely to become infected. The numbers of bacteria and duration of exposure, the virulence of the organism, the antibiotic resistance of the organism and the presence of opportunistic bacteria are important risk factors in the pathogenesis of infection. Common organisms found in skin infections are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. When Staphylococcus aureus is cultured, an antistaphylococcal penicillin such as flucloxacillin is indicated. For Streptococcus pyogenes infections benzyl penicillin is usually curative. In severe cases of infection with either organism the antibiotic should be given parenterally. In the penicillin-allergic patient erythromycin is an acceptable alternative. Early antibiotic treatment facilitates local and systemic control of infection. Initially the nature of the organism is often unknown; the type of antibiotic selected is then chosen with a view to the most likely organism, based upon clinical guidelines.

Specific infections of skin and subcutaneous tissues

Clinical features and treatment plan

2 Folliculitis, furuncle, carbuncle, hydradenitis

Furuncles (boils) and carbuncles. These are more florid forms of folliculitis. Boils are staphylococcal abscesses of hair follicles. Abscess formation involves the entire hair follicle and adjacent subcutaneous tissue. The condition is contagious and multiple furuncles are common (furunculosis). Furunculosis normally occurs in young adults with acne and abnormal skin function related to hormonal changes or seborrhoeic dermatitis. Boils may be the presenting symptom of diabetes mellitus. The follicular abscess becomes fluctuant and spontaneously discharges a soft core of necrotic pus after several days. The treatment of a furuncle is minimal incision and drainage, with removal of the hair. Antibiotics are not indicated unless the boil is in an area such as the upper lip, nose or eye, where septic phlebitis and cavernous sinus thrombosis are real risks of spreading infection. Washing with an antiseptic to reduce the skin burden of staphylococci is advisable for recurrent furunculosis. When furunculosis is associated with severe acne vulgaris, long-term tetracycline may be of value.

3 Erysipelas, cellulitis, impetigo

Cellulitis usually affects the extremities as an area of brawny, hot, oedematous skin without a clear border. Blistering, necrosis and ulceration can develop quite rapidly and may involve the fascia and muscles. Cellulitis is seen frequently in the legs of susceptible patients (e.g. drug addicts and alcoholics) and in patients with oedema from chronic lymphoedema, venous insufficiency or heart failure. Sometimes cellulitis is secondary to arterial insufficiency. Patients with chronic lymphatic oedema are particularly prone to recurrent skin infections. A foreign body from previous injury or underlying osteomyelitis are other important precipitating lesions. Radiological imaging is essential to detect these two predisposing causes. Bacteria may be difficult to obtain for culture but blood culture may be positive. Therapy entails rest, elevation and penicillins — with drainage of any focus of pus, if detected. Failure to respond within 24 hours suggests the need to change antibiotics and that a further search for a hidden abscess should be made and more radical debridement considered.

4 Necrotising soft tissue infections

The wound is painful, crepitant and discoloured. The brownish discharge has a characteristic sickly sweet, ‘mousy’ odour. Shock, haemolysis, jaundice and renal injury follow unless surgical treatment is prompt. The most important consideration is prevention — by early and adequate primary care of all contaminated wounds, with delayed closure of high-risk wounds. The treatment of established myositis demands prompt radical surgery — sometimes amputation — to remove all dead or dubiously viable tissue and to establish free drainage. Penicillin is given in high doses. Gas gangrene antiserum has little or no place in management. Hyperbaric oxygenation may be of value in treatment but must not delay necessary surgical debridement.

5 Specific sites

Subcutaneous infections at specific sites often originate in a focus of established pathology and require special management. Under this heading may be included hand infections (Ch 6.8), perianal abscess (Ch 7.22), bursitis (Ch 6.11), fungal infections, cervical tuberculosis, infected rheumatoid nodules and Ludwig’s angina. Gout and occupational tenosynovitis are aseptic inflammatory lesions that can mimic cellulitis.

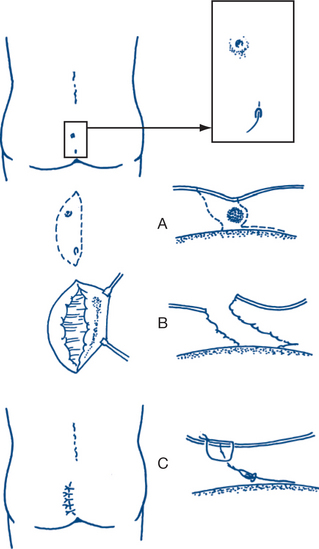

Chronic pilonidal sinus. For a chronic sinus, the aims of treatment are excising the sinus and contained hair, removing the midline sinus or pits and obliterating the natal cleft to prevent the entry of hair at new sites. Excision of the lesion in toto, with primary suture, is often performed as an elective procedure (Fig 1.13).

1.5 Lymph node swellings

Clinical assessment

Generalised lymph node swellings

Generalised lymphadenopathy with hepatosplenomegaly occurs with systemic infections and with haemopoietic and other malignancies. In chronic myeloid leukaemia, the spleen is often enlarged to a much greater degree than the lymph node enlargement; in lymphatic leukaemia the reverse applies.

Diagnostic and treatment plans

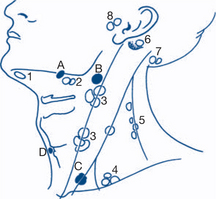

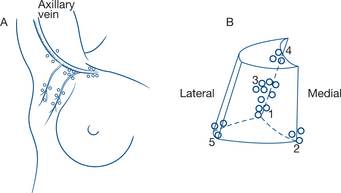

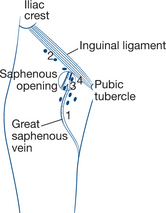

Figures 1.14–1.16 show lymph nodes in the neck, axilla and groin respectively.