Chapter 22 Integrative Medicine in Rehabilitation

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine. These therapies are either complementary to standard medical therapies (used with) or alternative to (used in place of) orthodox treatments. CAM is popular in both North America16,49 and Europe. The U.S. National Institutes of Health organized the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM; http://nccam.nih.gov/)17,101,103 in 1998 to advance the study of these therapies.

The term integrative medicine is now widely used to describe the practice of combining mainstream medical therapies and CAM therapies for which there is some high-quality scientific evidence of safety and effectiveness.17,101,103 Although many CAM treatments have not been properly studied, there are many that can be safely integrated into physical medicine and rehabilitation practice.

CAM therapies have been categorized by NCCAM17,101,103 into the following groups:

Alternative Medical Systems

Chiropractic

Chiropractic is a profession founded on the theory that minor spinal misalignments can detrimentally affect the neurologic function of spinal nerves and the organs and structures supplied by those nerves (see Chapter 19). These misalignments are often called subluxations. The chiropractic use of the term subluxation is not congruent with the medical definition, which requires partial dislocation of a joint. This disparity not uncommonly leads to confusion between practitioners and patients when discussing their condition. Chiropractors treat subluxations with various interventions, the most common being spinal manipulation. Although much is written about subluxations, there is little agreement among chiropractors on how to define, detect, or treat them. Because these proposed lesions cannot be reliably measured or detected (and are therefore difficult to study), their effect on health is unclear. Despite this, there are many randomized controlled studies of chiropractic treatments for various conditions, particularly musculoskeletal disorders such as back pain and neck pain. Spinal manipulation is considered to be the active intervention in most of those studies.

Chiropractors often incorporate other techniques, such as massage and exercise prescription, in treatment. They also use radiography to aid in diagnosis. Chiropractors do not dispense prescription medications or perform surgery or invasive treatments. A comprehensive report has detailed the chiropractic profession in the United States.38 There were approximately 53,000 chiropractors practicing in the United States in 2006.6 Many others practice in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Japan, and most northern European countries.

Osteopathic Medicine

Osteopathic medicine was founded in the United States in the late nineteenth century about the same time as chiropractic and has a similar underlying theory. Osteopathic theory holds that somatic lesions (similar in concept to the chiropractic subluxation) occur in the musculoskeletal system and can be treated by various forms of manual therapy, including spinal manipulation. In many ways osteopathic physicians are now indistinguishable from traditionally trained medical physicians because they have adopted most practices of Western medicine including prescription medicines and surgery. A subgroup of osteopaths, however, continues to use manual therapies to treat disease.

Homeopathy

Homeopathy’s central tenets are the principle of similars and the principle of dilution. The principle of similars, or “like begets like,” can be found in many systems of magical thought. In application the idea is that small quantities of an agent can ameliorate the same symptoms that are evoked in a healthy patient when given in larger quantities. For some practitioners, determination of the causative agent is as critical as matching the symptoms that are being treated (i.e., the complaint might not have been caused by a bee sting, but the patient is responding just like he or she was stung). The principle of dilution states that highly dilute solutions have biologic activity, and the more dilute the solution, the more potent the remedy. Some remedies are diluted but still possess measurable biologic activity. Others might be diluted to the point that efficacy could not be explained by conventional science (a solution could be so dilute that not every dose contains a single molecule of the active substance). Although most of these remedies are safe, their potential for interaction with other ingested substances can be difficult to predict. Homeopaths typically seek to identify substances or agents that can reproduce the patient’s symptoms. Many substances are studied and cross-referenced in the homeopathic literature. Computerized tools are available for matching symptoms to a specific remedy to aid the homeopath in the selection of an appropriate treatment. Despite this practice being incongruent with science, there is some evidence of effect. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial demonstrated benefit from homeopathic treatment of mild traumatic brain injury.37 Another trial found benefit in treating tendinopathy.121 Other studies have not found benefit. A study of homeopathic therapy after knee ligament reconstruction failed to find benefit.109 Similarly, a trial of homeopathy to improve muscle tone in children with cerebral palsy also failed to find a significant effect.120 Although there are some intriguing possibilities represented in the literature, current evidence does not appear to be sufficient to suggest a significant role for homeopathy in medical practices.

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Disease can manifest in a number of different ways. Sometimes disturbances have a material manifestation, altering blood, tissues, or the organs. At other times they manifest as more energetic (qi) symptoms such as fatigue, anxiety, or depression. Diagnosis of disease focuses on eliciting a history to determine the underlying disturbance. The TCM examination might include determining the characteristics of pulses at specific locations on the body, the appearance of the tongue, and the characteristics of olfaction, as well as carefully palpating the body. This information aids the TCM practitioner in the diagnosis of an individual’s complaint. A diagnosis in TCM (such as ascending fire of the liver or kidney qi deficiency) might have no analog in the allopathic model.

Mind-Body Therapies

NCCAM identifies mind-body practices as those that “focus on the interactions among the brain, mind, body, and behavior, with the intent to use the mind to affect physical functioning and promote health.”103 Included in this group are such therapies as cognitive-behavioral therapy, meditation, prayer, and guided imagery, and therapies using creative outlets (e.g., art, music, and dance therapies).

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Although often included as a CAM therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy has moved into the mainstream of conventional medical practice. It integrates the cognitive restructuring approach of cognitive therapy with the behavioral modification techniques of behavioral therapy. A therapist typically works with patients to identify thoughts and behaviors that are maladaptive and attempts to change their thought patterns, leading to a change in behavior. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been successfully used for a variety of conditions, including insomnia,131 fibromyalgia,144 headache,3 pain,47 and low back pain.41,89

Meditation

The definition of the act of meditation according to the American Heritage Dictionary2 is ”to train, calm, or empty the mind, often by achieving an altered state, as by focusing on a single object.” Meditation is also frequently described as self-regulation of attention. It is perhaps one of the most commonly used mind-body modalities and is a significant component of many of the world’s major religions. There are numerous types of meditation (e.g., transcendental, mindfulness, and focused meditation). Much of the current interest in meditation can be traced to the 1970s work of Dr. Herbert Benson, who studied the physiologic responses to meditation. It was this early work by Benson22 that led to the identification of the “relaxation response.” Most patients use meditation to help manage stress and anxiety.18,34,116 However, there are numerous specific applications such as helping deal with pain,13 improving quality of life after brain injury,20 and improving irritable bowel syndrome.71 A small study found that older adults with chronic back pain benefited from meditation.98 A study of practitioners of transcendental meditation revealed that over a span of 5 years, health care utilization was significantly reduced in those who meditated regularly.108

Guided Imagery

Guided imagery is a technique that uses images or symbols to train the mind to create a physiologic or psychologic effect. This process, often guided by a practitioner or audiotape, has been used to reduce anxiety and pain, and to relieve physical problems caused by stress. Studies suggest it might have benefit in treating headaches,94 recurrent abdominal pain in children,14 depression,128 and fibromyalgia.54

Spirituality

Spirituality has been described as an awareness of something greater than the individual self. Some have argued against the inclusion of spirituality in the CAM realm, recognizing that spirituality is a part of normal life for a majority of people, regardless of cultural origin. The mind-body-spirit emphasis frequently found in CAM disciplines, however, has usually led to its inclusion in CAM therapy discussions. Although spirituality can take many forms, typically it involves prayer, either for one’s self or another. It can be pursued alone or in a group (e.g., church or synagogue). There are many possible psychologic benefits of spiritual awareness and focus, including reduction of stress and anxiety and the creation of a positive attitude. However, rigorous scientific studies of the effects of spirituality are relatively few. One study reported that spirituality can play an important role in rehabilitation.35

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy uses essential oils, distilled from plants, to improve mood, health, or both. Scents can be inhaled or applied in oil during massage. For inhalation a few drops of the essential oil are placed in steaming water, diffusers, or humidifiers that are used to spread the steam-oil combination throughout the room. They can also be added to bath water. For application to the skin, the oils are combined with a carrier, usually vegetable oil. Early clinical trials suggest aromatherapy might have some benefit as a complementary treatment in reducing stress, pain, and depression.33,76

Expression- and Art-Based Therapies

The American Art Therapy Association defines art therapy as the “therapeutic use of art making, within a professional relationship, by people who experience illness, trauma, or challenges in living, and by people who seek personal development.”4 It uses creative activities to help patients with physical and emotional problems. Proponents claim that both the creative process and the final work can help express and heal trauma. Patients can create paintings, drawings, sculptures, and other types of artwork, and can work individually or in groups. Art therapists typically have a master’s degree in art therapy or a related field. They help patients express themselves through the art they create. They also discuss emotions and concerns that patients might identify as they work on their art.

Music therapy is the use of specific music (with specific vibration frequencies) to promote relaxation and healing. Although most healing music is soft and soothing, individual patient preferences (jazz, classical, etc.) can also be relaxing and healing to that individual. Music is used to help patients express deep-set emotions, both positive and negative. It is thought to be helpful in treating autism, mentally or emotionally disturbed children and adults, elderly and physically challenged persons, and patients with schizophrenia, nervous disorders, or stress. Music therapists design music sessions for individuals and groups based on individual needs and tastes. Some aspects of music therapy include music improvisation, receptive music listening, song writing, lyric discussion, imagery, music performance, and learning through music. Individuals can also perform their own music therapy at home by listening to music or sounds that help relieve their symptoms.80,141

Dance therapy is “the psychotherapeutic use of movement to promote emotional, cognitive, physical and social integration of individuals.”12 It is sometimes also referred to as movement therapy. From a physical standpoint, dance therapy can provide exercise, improve mobility and muscle coordination, and reduce muscle tension. From an emotional standpoint, dance therapy has been reported to improve self-awareness, self-confidence, and interpersonal interaction, and is an outlet for communicating feelings.66

Biologically Based Therapies

Select Dietary Supplements Frequently Encountered in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Practice

Chondroitin Sulfate

Evidence

Numerous studies have been conducted on chondroitin, chondroitin and glucosamine, and glucosamine. Most indicate that these two supplements, either in combination or by themselves, are modestly effective at relieving symptoms of osteoarthritis. The multicenter, double-blind, placebo- and celecoxib-controlled Glucosamine/chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) reported on 1583 patients with knee arthritis.42 Significant effects were seen in the subgroup of patients with the most severe pain, but not in those with lesser symptoms. Although it was reported as a “negative” trial, several concerns emerged after the study was reported, including that the placebo response was unexplainably high. Consequently there is still active debate about the proper role of these agents in the management of arthritis symptoms.

Proponents believe that chondroitin acts as a substrate needed for joint matrix structure.72 If this mechanism is indeed correct, the finding that it could require at least 2 to 4 months of therapy before significant improvement is noted is not surprising.84 A number of studies have suggested that adding chondroitin sulfate to a conventional analgesic or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) is synergistic, possibly allowing reduction or elimination of those agents.84,99

Glucosamine Sulfate

Evidence

Studies of efficacy have been centered on knee osteoarthritis. Most studies evaluating glucosamine sulfate for knee osteoarthritis have been positive.96 Glucosamine was found to be effective for osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine in one study.53 Some studies suggest efficacy equivalent to certain NSAIDs.90 Like chondroitin, onset of relief is generally delayed, requiring up to 8 weeks for full effect. In addition to symptom control, glucosamine might also have disease-modifying properties. Long-term studies suggest that treatment with glucosamine might result in significantly less joint space narrowing and knee joint degeneration as compared with placebo.115

S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine

Evidence

A number of clinical trials suggest that S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) is superior to placebo and comparable to NSAIDs for decreasing symptoms associated with osteoarthritis.59,77,102 The full effect might require up to 1 month of treatment. The mechanism of action is thought to include stimulation of articular cartilage growth and repair.27

Bromelain (Ananas comosus)

Evidence

Bromelain, taken in conjunction with trypsin and rutin, resulted in decreased pain and improved knee function in patients with osteoarthritis.73 A study of knee pain in otherwise healthy adults also showed evidence of benefit.138 However, a subsequent trial of bromelain alone did not demonstrate any benefit in patients with knee osteoarthritis.30

Camphor (Cinnamomum camphora)

Evidence

Camphor is Food and Drug Administration–approved as a topical analgesic. A topical cream containing camphor, glucosamine sulfate, and chondroitin sulfate was found to provide reduction in pain caused by osteoarthritis.43 Because there is no evidence that glucosamine and chondroitin can be absorbed topically, the relief might have resulted from the counterirritant effect of camphor, but these data should be considered inconclusive.

Cat’s Claw (Uncaria tomentosa)

Evidence

Found in Peru, cat’s claw is a large vine with curved thorns, resembling the claws of a cat. It is touted as an effective remedy for a number of conditions. In the United States many patients have been attracted to claims of its antiinflammatory effects, but there are no well-designed studies in this regard. One study found that a freeze-dried cat’s claw extract relieved knee pain related to physical activity, but did not affect pain at rest.112 Modest effects were seen in another trial of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.100 The mechanism of action is uncertain but might be inhibition of the production of prostaglandin E2 and tumor necrosis factor-α.

Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens)

Dimethylsulfoxide

Evidence

Although not as popular as in the 1980s and 1990s, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) is still used by many patients as a topical treatment for osteoarthritis. There is limited evidence that it might have efficacy in this regard.118,135

Adverse Effects

DMSO is readily absorbed through the skin, so even topical application can result in systemic effects. Adverse effects include sedation, headache, dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and anorexia. Many people also experience skin changes (erythema, pruritus, burning, blistering, drying, and scaling).144

Evening Primrose Oil (Oenothera biennis)

Evidence

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of rheumatoid arthritis, evening primrose oil resulted in a significant reduction of symptoms.21 Evening primrose oil contains γ-linolenic acid), which is thought to have antiinflammatory properties.

Adverse Effects

There are no reports of significant side effects.

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 created a separate supplement classification known as “dietary supplements” that covers the use of herbs, vitamins, amino acids, and even certain hormones such as dehydroepiandrosterone and melatonin. As dietary supplements, they are neither subject to the stringent food safety rules nor are they considered over-the-counter medications or drugs. This permits them to escape traditional oversight mechanisms in the United States. As a result, it is difficult for physicians to monitor patient use of these products. Further, the Act specifically states that manufacturers of dietary supplements are not required to prove the safety and efficacy of their products before going to market, which has created a true “caveat emptor” requirement on the part of the consumer when purchasing dietary supplements. Fortunately, in 2007, the United States Food and Drug Administration passed a Good Manufacturing Practices rule. This rule requires that dietary supplements sold in the United States be “manufactured consistently as to identity, purity, strength, and composition.”5 When fully implemented in 2010, this rule will help ensure the quality of these products in the United States.

Manipulation and Body-Based Therapies

Manipulation and Mobilization

Manipulation (typically inferring to high-velocity thrust techniques applied to a joint) and mobilization (nonthrust, oscillatory techniques) have been used for centuries to treat various conditions. In North America and Europe, they are often used by chiropractors, physical therapists, and physicians to treat musculoskeletal conditions, most commonly low back pain. Although the systems of patient evaluation and treatment vary and the taxonomies are often different, the techniques used are remarkably similar. There is no evidence that manipulation or mobilization applied by one profession is more or less beneficial than when provided by a competing profession. The goal of these therapies is to normalize motion and tension about a joint. Some professions, chiropractic in particular, infer health benefits beyond the reduction of pain and improvement in musculoskeletal function, but evidence for these claims is very limited. (See also Chapter 19.)

Minor side effects of spinal manipulation are common. At least one unpleasant reaction was experienced after manipulation by more than half of patients, with the most frequent being local discomfort (53%), headache (12%), tiredness (11%), and radiating discomfort (10%). Reactions were mild or moderate in 85%, and were typically short-lived (74% resolved within 24 hours). Uncommon reactions such as dizziness and nausea accounted for less than 5% of the symptoms, and no serious complications were reported.122

Complications of thoracic and lumbar manipulation are listed in Box 22-1. They are rare, and investigators agree that the risk-to-benefit ratio of manipulation for low back pain is acceptable in most patients.8,114 The most serious complication of lumbar manipulation is cauda equina syndrome. About half of the reported cases occurred during manipulation under anesthesia.8 Haldeman and Rubinstein63 noted 10 cases of cauda equina syndrome that were not associated with manipulation under anesthesia, and reported three additional cases. Those cases represented treatment by chiropractors, osteopathic and allopathic physicians. The frequency of cauda equina syndrome has been estimated to be one in several million treatments.63,124

Complications of cervical manipulation are also listed in Box 22-1. Although relatively rare, they are often more serious than those associated with lumbar or thoracic manipulation. Noncerebrovascular complications can usually be prevented by excluding patients with contraindications to manipulation.9 The most controversial issue concerning spinal manipulation is the relationship between cervical manipulation and stroke. Cervical manipulation can cause mechanical stress on the vertebral arteries, resulting in vertebrobasilar stroke.9 The most common site of injury appears to be the extracranial third segment of the vertebral artery.19,67,79 Permanent and severe neurologic injury and even death can result. For this reason, some have argued that the risk-to-benefit ratio of cervical manipulation is unacceptable.114 Proposed risk factors such as vessel anomalies, spondylosis, and hypertension have been largely absent in persons sustaining vertebral artery injury.55 It is difficult to study the frequency of stroke after a single cervical manipulation, but it has been estimated to be 1 case per 400,000 to 3 million cervical manipulation.48,125 Hurwitz et al.68 estimated 5 to 10 serious complications and 3 deaths for every 10 million cervical spine manipulations. A Danish study found the risk of death or permanent sequelae to be 1 in 1.3 million treatments.74

A screening test using neck extension and rotation has been thought to predict patients at risk of vertebrobasilar stroke, but its value is questionable at best.44 Haldeman et al.62 reviewed the literature related to vertebrobasilar artery dissection and found no specific neck movement, position, or type of manipulation to be associated with it, and a specific population at risk for dissection could not be identified. They concluded that although some unique but as yet unidentified factor might predispose to vertebrobasilar dissection, there is little evidence to support the contention that cervical manipulation or any other neck motion, position, or injury is a significant risk for these occurrences.

Relative and absolute contraindications for spinal manipulation are listed in Box 22-2.9,64 Although most past recommendations have been based on sound rationale, some have not been supported by scientific evidence. For example, disk herniation has often been listed as a contraindication for lumbar manipulation, but chiropractors and therapists commonly use it to treat persons with disk herniation. Another reported contraindication is lumbar spondylolisthesis, but these patients appear to respond as well as those with normal spinal anatomy.97

The most common condition treated with manipulation and mobilization is low back pain. Because the effect size is small (as it is for all treatments for back pain), trials have sometimes reached conflicting conclusions. This has resulted in many metaanalyses attempting to determine the appropriate use of manual therapy techniques. The reviews with higher methodologic quality that have concentrated on randomized controlled trials have reached overall positive conclusions.10 The best evidence supports the use of manipulation for most types of uncomplicated acute and chronic low back pain,82 but there is no compelling evidence that it is more efficacious than other commonly used therapies.11

After low back pain, neck pain is the next most common complaint treated with manipulation and mobilization. The data are far less convincing than those for low back pain. Recent metaanalyses have found limited evidence of efficacy and have arrived at nearly the same conclusions: (1) there are very few high-quality studies, and (2) there is some evidence for the effectiveness of manipulation and mobilization for neck pain especially when combined with exercise.60,137

Data from a variety of sources indicate that many patients with headache seek manual therapy. A survey by Eisenberg et al.50 found that 27% of subjects with headaches used a nonmedical therapy within the previous 12 months, and chiropractic was sought most often. The use of spinal manipulation as treatment for headaches is predicated on the cervical spine being a contributing factor in the etiology of headaches. This theoretic mechanism is based on the convergence of two peripheral systems of nociception: the trigeminal system and the cervical spinal nerves (particularly from C1 to C3). The functional effect of this convergence is that the nociceptive input from these two systems is poorly localized, and pain arising from one system can be interpreted subjectively as coming from the other. In this model, cervical spine dysfunction that produces pain can be experienced as a headache.24,25 Bovim et al.29 were able to demonstrate experimentally that disorders of the cervical spine could cause headaches. Another possible connection between the cervical spine and headache is an anatomic connection between the rectus capitus posterior minor muscle and the spinal dura via a dense connective tissue bridge at the level of the occiput-atlas junction.61

The evidence for the use of spinal manipulation for headache is primarily from five randomized clinical trials. Two studies104,110 examined migraine headache; two,26,28 tension-type headache; and one,106 cervicogenic headache. When compared with some forms of medical prophylaxis for both tension-type and migraine headaches, spinal manipulation appears to offer similar relief. It is not clear to what extent nonspecific treatment effects contribute to this benefit. There are no known factors that differentiate headache patients who benefit from manipulation and mobilization from those who do not. The long-term benefits (>1 month) are unknown. These treatments do not appear to be effective in aborting headaches.

There is little evidence to suggest that manipulation or mobilization can correct or reduce idiopathic scoliosis.107,113 There is, however, a suggestion that spinal manipulation therapy is helpful in controlling chronic mechanical back pain associated with scoliosis.133

Although manual medicine practitioners have reported alleviation of symptoms caused by carpal tunnel syndrome and normalization of nerve conduction studies,136 there is little evidence to suggest a therapeutic effect.45

Shekelle123 has noted that “there appears to be little evidence to support the value of spinal manipulation for nonmusculoskeletal conditions.” Randomized controlled trials of chiropractic treatment for asthma have demonstrated no change in measured lung functions in either children15 or adults.105 Although otitis media is sometimes treated by chiropractors, there have been no randomized trials. A review of the literature concluded that the effect of spinal manipulation on enuresis is similar to the natural remission rate.78 Primary dysmenorrhea has been reported to respond to spinal manipulative therapy.32,85 A single randomized trial demonstrated reduction in pain and menstrual distress. The control (sham manipulation) and treatment groups had similar elevations in circulating prostaglandins, indicating that the effect may have been the result of nonspecific factors.75 There is no evidence that manual therapies are beneficial for central nervous system–based disorders such as epilepsy.

Movement Therapies

Feldenkrais Method

The Feldenkrais Method is a system of body movement education that is believed to enhance awareness of movement and improve functional movement. The underlying theory is that poor habitual movement patterns result in injury and pain. The expected results of Feldenkrais therapy (awareness through movement classes or functional integration sessions) are that a person will be able to move more efficiently and comfortably, and with less pain. Feldenkrais practitioners undergo an extensive apprentice-like training program. Although the popular press promotes this therapy for many conditions, there are few randomized studies of the Feldenkrais Method. A nonrandomized study in patients with nonspecific musculoskeletal pain syndromes found no difference between conventional physical therapy, body awareness therapy, and the Feldenkrais Method as reflected by medical outcomes study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey subscale scores.92 A small randomized study of the effect of Feldenkrais on pain found the affective dimension (attitude toward the pain) to be reduced, but no change was measured in other dimensions.129 A small randomized trial found patients with neck and shoulder complaints to benefit more from Feldenkrais than physical therapy.91 There is theoretic potential for benefit in numerous conditions because of possible effects on motor control, but this therapeutic paradigm has been inadequately studied.69

Alexander Technique

The Alexander technique is a psychophysical reeducation method that proposes to relieve muscular tension and improve the efficiency of movement. The technique involves examination of posture, breathing, balance, and coordination, and has three underlying principles: (1) an organism functions as a whole; (2) a person’s ability to function optimally is dependent on the relationship of the head, neck, and spine; and (3) body function is affected by habitual patterns of use. The Alexander technique is often advocated in the treatment of asthma, headaches, arthritis, and pain, and is often used by performing artists.51 The evidence supporting the use of the Alexander technique is very limited and at this point inconclusive,52 although at least one randomized trial has demonstrated benefit for persons with chronic low back pain.89

T’ai Chi

Tái chi is an ancient exercise form that originated in China. Various forms of it are practiced today, and it has become a popular physical activity in North America and Europe. It has been advocated as a therapeutic exercise, particularly in the elderly. Tái chi has been reported to improve balance, flexibility, and cardiovascular fitness in geriatric patients.139,145,146 A Cochrane systematic review found only four trials that had appropriate control groups. No statistically significant or clinically meaningful effect was found for most outcomes measured, although significant increases in range of motion were noted.65 In spite of this, tái chi appears to be a safe form of exercise for most individuals, even the elderly.

Pilates

Pilates exercises were originally designed for and used by performance artists, but have enjoyed wider popularity in recent years. It is estimated that 5 million people now use them, largely because of mass marketing. There are at least two randomized studies examining the effects of Pilates exercises on back pain. A randomized controlled trial (n = 39) with 12-month follow-up comparing specific Pilates exercises (using specialized exercise equipment) with usual medical care found the Pilates group to have lower disability scores and pain ratings after the intervention, with the improved disability scores maintained at 12 months.119 In another study 53 subjects were randomized to receive either pilates treatment or referral to a back school and exercise program for chronic low back pain, with blinded observers and 6-month follow-up. Both groups improved similarly in regard to disability and pain, although the Pilates group had better compliance and perceived benefit.47

Yoga

Yoga is part mind-body therapy and part stretching and breathing exercise. It is most appropriately addressed with movement therapies. It is commonly advocated as treatment for musculoskeletal conditions including arthritis58 and carpal tunnel syndrome.58 There are few controlled studies in the literature. Yoga appears to have some beneficial effect on asthma, but the mechanism of effect is unclear.95 It might be beneficial for hypertension as well.111 A randomized trial of yoga, exercise, or a self-care book for low back pain found the yoga group to have improved function compared with the book and exercise groups at 12 weeks, but there were no significant differences in the “bothersomeness” of symptoms. At 26 weeks, back-related function in the yoga group continued to be superior to the book group.126

Energy Therapies

Acupuncture

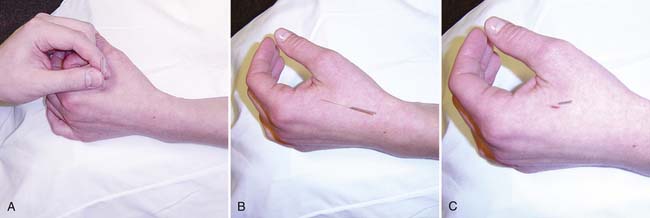

Originating in ancient China, acupuncture is one of the best recognized CAM treatments. Acupuncture consists of the insertion of thin, flexible needles into the body at specific points to improve health (Figure 22-1). The needles are inserted to varying depths and angles, and typically are inserted superficially (Figure 22-2). The needles can be further stimulated in a number of ways, including twirling the needles, electrical stimulation, or burning an herb placed on the end of the needle outside the patient. In the United States acupuncture is most widely used for analgesia or relief of pain, but it is also used to treat a wide range of other conditions including asthma, fatigue, gastrointestinal disturbance, and infertility.

A wide range of practitioners perform acupuncture. State laws vary, but acupuncture practitioners include physicians (MDs), osteopaths (DOs), chiropractors (DCs), and licensed acupuncturists (LAcs). In some states, acupuncture can be performed as part of a religious ceremony. With such a diverse group of practitioners, there is considerable variability in the approach to acupuncture. Given its historical origin, acupuncture is most commonly associated with TCM (see earlier discussion). Acupuncture in this setting is often provided with recommendations regarding diet, herbal remedies, exercises, massage, and lifestyle modification.

Acupuncture is a modality that is generally safe, with a growing but not definitive evidence base regarding its effectiveness for many conditions frequently seen in a physical medicine and rehabilitation practice. Conditions commonly treated with acupuncture in the rehabilitation medicine setting are listed in Box 22-3. It is most often used after therapies with more evidence of efficacy have been tried and failed. There is considerable anecdotal evidence and a large number of clinical trials that support its use. In the 1990s, high-quality evidence for the efficacy of acupuncture was scant.1 Individual studies often demonstrated benefit for multiple conditions, but they were usually small, less rigorous, and difficult to reproduce. In addition, there was a question of publication bias; Asian studies tended to report more favorable results than those studies performed in the United States. Larger, more rigorous trials have now demonstrated less favorable results for many conditions. Several difficulties continue to produce controversy in acupuncture research. The difficulty of establishing adequate sham procedures and the variability in study design continue to be of concern. Also, the precision of the diagnosis is lacking, because patients are classified by symptoms rather than by objective criteria or specific medical diagnoses. Acknowledging this complex background, recent trials show a generally positive effect on knee osteoarthritis symptoms,22,70,93,117 chronic low back pain,56 and headaches.86,87 There is also evidence that acupuncture added to standard treatment is beneficial for fibromyalgia.132

The literature regarding acupuncture safety indicates only a low rate of complications, even among acupuncture students.1 Risks for acupuncture include bleeding, infection, and organ puncture (including pneumothorax).81 Needle shock is an uncommon side effect that typically occurs during the first acupuncture treatment. The description of this event is similar to a vasovagal episode: sweating, flushing, and the sensation that the world is being seen from down a long tunnel. Treatment of needle shock is the immediate removal of the needles. A technique that is particularly prone to complications is the permanent placement of needles. These needles are inserted, and the handles are broken off.39 Unfortunately, they can migrate and cause damage to internal organs.

Reiki and Healing Touch

A number of trials using reiki and healing touch are currently being conducted by the National Institutes of Health. Completed studies suggest that both of these modalities might be effective in reducing psychologic sequelae of disease, such as pain. A Cochrane review concluded that use of reiki (versus other touch modalities) by experienced practitioners might result in a greater degree of pain relief.131

Reflexology

Research on reflexology has produced mixed results. As with many of the other energy treatments listed above, methodological flaws are prevalent in a large number of studies. Large well-designed studies are not available. Small studies suggest that it might be helpful for some conditions. For instance, it can possibly help spasticity, paresthesias, and urinary symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis.127 Yet it was found not to be helpful for irritable bowel syndrome.134 It is uncertain whether this variability is secondary to reflexology’s efficacy, the variation in how reflexology is practiced, or poor study design.

Electromagnetic Fields and Magnets

Unlike the energy medicine techniques discussed above that defy scientific attempts to characterize their energies, electromagnetic fields are well-defined physical phenomena that are widely used in technology. Electromagnetic fields are very familiar to physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians and are used in testing, such as MRI scans, electromyography, and electrocardiograms. The human body is composed of multiple structures and molecules that are highly charged and therefore particularly sensitive to strong magnetic fields. Magnets of varying field strengths and polarity can be applied to the body. Although the theoretic framework is in place, clinical effects of magnetic therapy have not been demonstrated. The data from trials on this modality are mixed, with the majority reporting no significant improvement in the condition being studied. Most studies have investigated magnetic therapy as a treatment for a specific condition, such as rotator cuff disorder,23,83 rather than for a general class of conditions.

How to Discuss Integrative Medicine With Your Patient

Many physicians feel challenged by CAM topics, particularly those whose training occurred before the boom in interest in CAM. They can feel inadequately trained or educated to make sound recommendations regarding the use or avoidance of supplements, interventions, or both. At the same time, many patients feel that they have been dismissed when raising questions regarding CAM or integrative medicine. As a result, they become “gun shy” about asking such questions of their physician. Additionally, surveys have shown that patients frequently consider therapies such as herbs “natural” and therefore not of interest to their physician. As a result, patients may withhold information because they do not recognize the importance of their physician knowing about their use of CAM therapies. Either way, both physicians and patients need to make a concerted effort to discuss integrative medicine approaches as part of the physician-patient encounter.

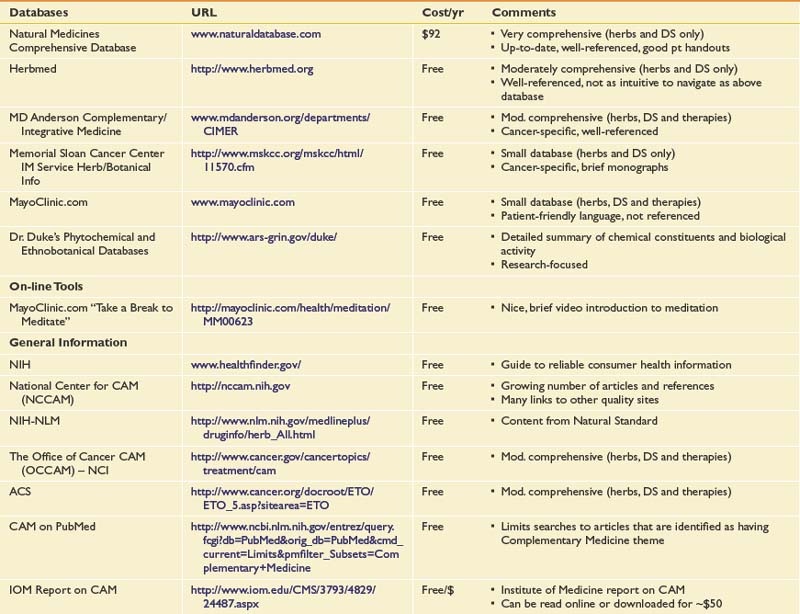

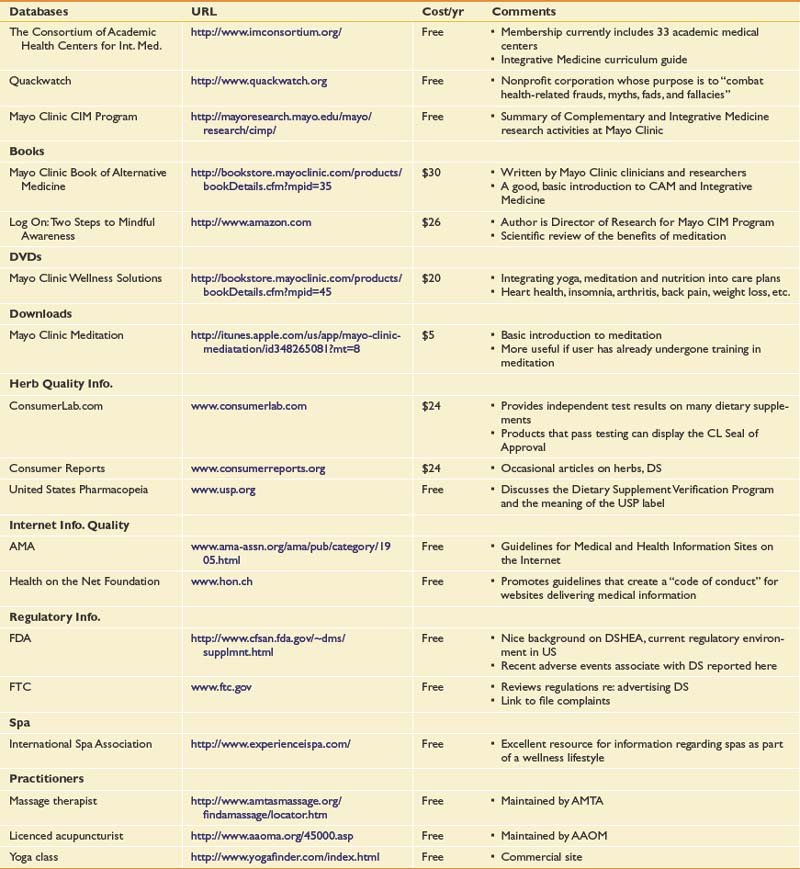

The obvious challenge in this setting is for the physician who has not had significant training in integrative medicine or CAM to know how to respond when the patient does reply in the affirmative to these inquiries. Many institutions have physicians or pharmacists who have received extra training in dietary supplements, including their risks and potential benefits. These individuals can be excellent resources. For dietary supplements, there is a wealth of reliable websites that can be queried. Online sources are of particular help in finding information regarding other specific therapies as well (Table 22-1).

The goal of discussing integrative medicine with a patient is to provide patient education. This is a critically important goal. Much of the information that patients are otherwise exposed to is commercial in intent and fraught with misinformation. The physician can fulfill the classic role of healers throughout the centuries, that of a teacher, by providing a safe environment for the patient to obtain information about these CAM therapies. By providing the patient with reliable, evidence-based information about the risks and benefits of a therapy, and by collaborating with the patient, the clinician can be an ally to the patient who is trying to navigate the complex realm of integrative medicine.

1. NCDPo Acupuncture: NIH Consensus Conference. Acupuncture. JAMA. 1998;280:1518-1524.

2. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, ed 4. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2000.

3. Andrasik F. Behavioral treatment approaches to chronic headache. Neurol Sci. 2003;24(suppl 2):S80-S85.

4. [Anonymous]. About art therapy (American Art Therapy Association), 2004. Available at: http://www.arttherapy.org/aboutarttherapy/about.htm. Accessed June 28, 2005.

5. [Anonymous]. Fact sheet: dietary supplement current good manufacturing practices (CGMPs) and interim final rule (IFR) facts (United States Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition). Available at: http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/dscgmps6.html. Accessed March 20, 2009.

6. [Anonymous]. Occupational outlook handbook, 2008-09 edition (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor), 2008. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos071.htm. Accessed March 23, 2009.

7. [Anonymous]. SAMe for depression. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1999;41:107-108.

8. Assendelft W.J., Koes B.W., van der Heijden G.J., et al. The effectiveness of chiropractic for treatment of low back pain: an update and attempt at statistical pooling. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19:499-507.

9. Assendelft W.J.J., Bouter L.M., Knipschild P.G. Complications of spinal manipulation. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:475-480.

10. Assendelft W.J.J., Koes B.W., Knipschild P.G., et al. The relationship between methodological quality and conclusions in reviews of spinal manipulation. JAMA. 1995;274:1942-1948.

11. Assendelft WJJ, Morton SC, Yu Emily I., et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2006.

12. Association ADT. Who we are, 2000. Available at: http://www.adta.org/. Accessed July 8, 2010.

13. Astin J. Mind-body therapies for the management of pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:27-32.

14. Ball T., Shapiro D., Monheim C., et al. A pilot study of the use of guided imagery for the treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2003;42:527-532.

15. Balon J., Aker P.D., Crowther E.R., et al. A comparison of active and simulated chiropractic manipulation as adjunctive treatment for childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1013-1020.

16. Barnes P.M., Bloom B., Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. CDC National Health Statistics Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008.

17. Barnsley L., Lord S., Bogduk N. The pathophysiology of whiplash. Spine: State of the Art Reviews. 1993;7:329-353.

18. Barrows K., Jacobs B. Mind-body medicine: an introduction and review of the literature. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:11-31.

19. Barton J.W., Margolis M.T. Rotational obstruction of the vertebral artery at the atlantoaxial joint. Neuroradiology. 1975;9:117-120.

20. Bedard M., Felteau M., Mazmanian D., et al. Pilot evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention to improve quality of life among individuals who sustained traumatic brain injuries. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:722-731.

21. Belch J., Ansell D., Madhok R., et al. Effects of altering dietary essential fatty acids on requirements for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a double blind placebo controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:96-104.

22. Benson H., Beary J., Carol M. The relaxation response. Psychiatry. 1974;37:37-46.

23. Binder A., Parr G., Hazleman B., et al. Pulsed electromagnetic field therapy of persistent rotator cuff tendinitis: a double-blind controlled assessment. Lancet. 1984;1:695-698.

24. Bogduk N. Cervical causes of headache and dizziness. In: Grieve G.P., editor. Modern manual therapy of the vertebral column. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1986.

25. Bogduk N., Marsland A. On the concept of the third occipital headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:775-780.

26. Boline P.D., Kassak K., Bronfort G., et al. Spinal manipulation vs. amitriptyline for the treatment of chronic tension-type headaches: a randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18:148-154.

27. Bottiglieri T. S-Adenosyl-L-methionine. (SAMe): from the bench to the bedside—molecular basis of a pleiotrophic molecule. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:S1151-S1157.

28. Bove G., Nilsson N. Spinal manipulation in the treatment of episodic tension-type headache: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1576-1579.

29. Bovim G., Berg R., Dale L.G. Cervicogenic headache: anesthetic blockades of cervical nerves (C2-C5) and facet joints (C2/C3). Pain. 1992;49:315-320.

30. Brien S., Lewith G., Walker A.F., et al. Bromelain as an adjunctive treatment for moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. QJM. 2006;99:841-850.

31. Brien S., Lewith G.T., McGregor G. Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) as a treatment for osteoarthritis: a review of efficacy and safety. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:981-993.

32. Browning J.E. Pelvic pain and organic dysfunction in a patient with low back pain: response to distractive manipulation: a case presentation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1987;10:116-121.

33. Buckle J. Use of aromatherapy as a complementary treatment for chronic pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999;5:42-51.

34. Carlson L., Ursuliak Z., Goodey E., et al. The effects of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients: 6-month follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:112-123.

35. Chally P., Carlson J. Spirituality, rehabilitation, and aging: a literature review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:S60-S65. quiz S66–S67

36. Chantre P., Cappelaere A., Leblan D., et al. Efficacy and tolerance of Harpagophytum procumbens versus diacerhein in treatment of osteoarthritis. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:177-183.

37. Chapman E.H., Weintraub R.J., Milburn M.A., et al. Homeopathic treatment of mild traumatic brain injury: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14:521-542.

38. Cherkin D.C., Phillips R.B., Mootz R., et al. Chiropractic in the United States: training, practice, and research. Rockville: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997.

39. Chiu E.S., Austin J.H. Images in clinical medicine. Acupuncture-needle fragments. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:2.

40. Chou R., Huffman L.H., American Pain Society, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. [See comment.]. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:492-504. [Erratum: Ann Intern Med 2008; 148:247-248.]

41. Chrubasik S., Pollak S., Fiebich B. Harpagophytum extracts. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71:104-105.

42. Clegg D.O., Reda D.J., Harris C.L., et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. [See comment.]. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795-808.

43. Cohen M., Wolfe R., Mai T., et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of a topical cream containing glucosamine sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, and camphor for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:523-528.

44. Cote P., Kreitz B.G., Cassidy J.D., et al. The validity of the extension-rotation test as a clinical screening procedure before neck manipulation: a secondary analysis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19:159-164.

45. Davis P., Hulbert J.R., Kassak K.M., et al. Comparative efficacy of conservative medical and chiropractic treatments for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21:317-326.

46. Devine E. Meta-analysis of the effect of psychoeducational interventions on pain in adults with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:75-89.

47. Donzelli S., Di Domenica E., Cova A.M., et al. Two different techniques in the rehabilitation treatment of low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42:205-210.

48. Dvorak J., Orelli F. How dangerous is manipulation to the cervical spine? Manual Med. 1985;2:1-4.

49. Eisenberg D.M., Davis R.B., Ettner S.L., et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569-1575.

50. Eisenberg D.M., Kessler R.C., Foster C., et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-252.

51. Ernst E. Complementary and alternative medicine in rheumatology [review]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2000;14:731-749.

52. Ernst E., Canter P.H. The Alexander technique: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2003;10:325-329.

53. Foerster KK, Schmid K, Rovati LC: Efficacy of glucosamine sulfate in osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine: a placebo controlled, randomized, double-blind study, 64th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Denver, Co, October 29–November 2.

54. Fors E., Sexton H., Gotestam K. The effect of guided imagery and amitriptyline on daily fibromyalgia pain: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:179-187.

55. Frumkin L.R., Baloh R.W. Wallenberg’s syndrome following neck manipulation. Neurology. 1990;40:611-615.

56. Furlan A.D., van Tulder M., Cherkin D., et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2005;30:944-963.

57. Garfinkel M., Schumacher H., Husain A., et al. Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2341-2343.

58. Garfinkel M.S., Singhal A., Katz W.A., et al. Yoga-based intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1601-1603.

59. Glorioso S., Todesco S., Mazzi A., et al. Double-blind multicentre study of the activity of S-adenosylmethionine in hip and knee osteoarthritis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1985;5:39-49.

60. Gross A.R., Hoving J.L., Haines T.A., et al. A Cochrane review of manipulation and mobilization for mechanical neck disorders. Spine. 2004;29:1541-1548.

61. Hack G.D., Koritzer R.T., Robinson W.L., et al. Anatomic relation between the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle and the dura mater. Spine. 1995;20:2484-2486.

62. Haldeman S., Kohlbeck F.J., McGregor M. Risk factors and precipitating neck movements causing vertebrobasilar artery dissection after cervical trauma and spinal manipulation. Spine. 1999;24:785-794.

63. Haldeman S., Rubinstein S.M. Cauda equina syndrome in patients undergoing manipulation of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1992;17:1469-1473.

64. Haldeman S., Rubinstein S.M. Compression fractures in patients undergoing spinal manipulative therapy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992;15:450-454.

65. Han A., Robinson V., Judd M., et al. Tai chi for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD004849.

66. Hanna J. The power of dance: health and healing. J Altern Complement Med. 1995;1:323-331.

67. Hart R.G. Vertebral artery dissection. Neurology. 1988;38:987-989.

68. Hurwitz E.L., Aker P.D., Adams A.H., et al. Manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine, a systematic review of the literature. Spine. 1996;21:1746-1759.

69. Ives J.C., Shelley G.A. The Feldenkrais Method in rehabilitation: a review. Work. 1998;11:75-90.

70. Jubb R.W., Tukmachi E.S., Jones P.W., et al. A blinded randomised trial of acupuncture (manual and electroacupuncture) compared with a non-penetrating sham for the symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee. Acupunct Med. 2008;26:69-78.

71. Keefer L., Blanchard E. A one year follow-up of relaxation response meditation as a treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:541-546.

72. Kelly G. The role of glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfates in the treatment of degenerative joint disease. Altern Med Rev. 1998;3:27-39.

73. Klein G., Kullich W. Short-term treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee with oral enzymes. Clin Drug Investig. 2000;19:15-23.

74. Klougart N., Leboeuf-Yde C., Rasmussen L.R. Safety in chiropractic practice. Part I: the occurrence of cerebrovascular accidents after manipulation to the neck in Denmark from 1978-1988. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19:371-377.

75. Kokjohn K., Schmid D.M., Triano J.J., et al. The effect of spinal manipulation on pain and prostaglandin levels in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1992;15:279-285.

76. Komori T., Fujiwara R., Tanida M., et al. Effects of citrus fragrance on immune function and depressive states. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1995;2:174-180.

77. Konig B. long-term (two years) clinical trial with S-adenosylmethionine for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1987;83:89-94.

78. Kreitz B.G., Aker P.D. Nocturnal enuresis; treatment implications for the chiropractor. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:465-473.

79. Krueger B., Okazaki H. Vertebal-basilar distribution infarction following chiropractic cervical manipulation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:322-332.

80. Lane D. Music therapy: gaining an edge in oncology management. J Oncol Manag. 1993:44-46.

81. Lao L., Hamilton G.R., Fu J., et al. Is acupuncture safe? A systematic review of case reports. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:72-83.

82. Lawrence D.J., Meeker W., Branson R., et al. Chiropractic management of low back pain and low back-related leg complaints: a literature synthesis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:659-674.

83. Leclaire R., Bourgouin J. Electromagnetic treatment of shoulder periarthritis: a randomized controlled trial of the efficiency and tolerance of magnetotherapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:284-287.

84. Leeb B., Schweitzer H., Montag K., et al. A metaanalysis of chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:205-211.

85. Liebl N.A., Butler L.M. A chiropractic approach to the treatment of dysmenorrhea. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1990;13:101-106.

86. Linde K., Allais G., Brinkhaus B., et al. Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD001218.

87. Linde K., Allais G., Brinkhaus B., et al. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 (1):CD007587.

88. Linton S.J., Nordin E. A 5-year follow-up evaluation of the health and economic consequences of an early cognitive behavioral intervention for back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Spine. 2006;31:853-858.

89. Little P., Lewith G., Webley F., et al. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ. 2008;337:a884.

90. Lopes Vaz A. Double-blind clinical evaluation of the relative efficacy of ibuprofen and glucosamine sulphate in the management of osteoarthrosis of the knee in out-patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 1982;8:145-149.

91. Lundblad I., Elert J., Gerdle B. Randomized controlled trial of physiotherapy and Feldenkrais interventions in female workers with neck-shoulder complaints. J Occup Rehabil. 1999;9:179-194.

92. Malmgren-Olsson E., Branholm I. A comparison between three physiotherapy approaches with regard to health-related factors in patients with non-specific musculoskeletal disorders. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:308-317.

93. Manheimer E., Linde K., Lao L., et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:868-877.

94. Mannix L., Chandurkar R., Rybicki L., et al. Effect of guided imagery on quality of life for patients with chronic tension-type headache. Headache. 1999;39:326-334.

95. Manocha R., Marks G.B., Kenchington P., et al. Sahaja yoga in the management of moderate to severe asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2002;57:110-115.

96. McAlindon T.E., LaValley M.P., Felson D.T. Efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2000;284:1241.

97. Mierau D., Cassidy J.D., McGregor M., et al. A comparison of the effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain patients with and without spondylolisthesis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1987;10:49-55.

98. Morone N.E., Greco C.M., Weiner D.K. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: a randomized controlled pilot study. Pain. 2008;134:310-319.

99. Morreale P., Manopulo R., Galati M., et al. Comparison of the antiinflammatory efficacy of chondroitin sulfate and diclofenac sodium in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1385-1391.

100. Mur E., Hartig F., Eibl G., et al. Randomized double blind trial of an extract from the pentacyclic alkaloid-chemotype of uncaria tomentosa for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [comment]. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:678-681.

101. Nachemson A. The load on lumbar discs in different positions of the body. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1966;45:107-122.

102. Najm W.I., Reinsch S., Hoehler F., et al. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) versus celecoxib for the treatment of osteoarthritis symptoms: a double-blind cross-over trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:6.

103. NCCAM. What is complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)?. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; 2002.

104. Nelson C.F., Bronfort G., Evans R., et al. The efficacy of spinal manipulation, amitriptyline and the combination of both therapies for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21:511-519.

105. Nielsen N.H., Bronfort G., Bendix T., et al. Chronic asthma and chiropractic spinal manipulation: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25:80-88.

106. Nilsson N., Christensen H.W., Hartvigsen J. The effect of spinal manipulation in the treatment of cervicogenic headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:326-330.

107. Nykoliation J.W., Cassidy J.D., Arthur B.E., et al. An algorithm for the management of scoliosis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1986;9:1-14.

108. Orme-Johnson D. Medical care utilization and the transcendental meditation program. Psychosom Med. 1987;49:493-507.

109. Paris A., Gonnet N., Chaussard C., et al. Effect of homeopathy on analgesic intake following knee ligament reconstruction: a phase III monocentre randomized placebo controlled study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:180-187.

110. Parker G.B., Tupling H., Pryor D.S. A controlled trial of cervical manipulation of migraine. Aust N Z J Med. 1978;8:589-593.

111. Patel C., North W. Randomised controlled trial of yoga and bio-feedback in management of hypertension. Lancet. 1975;2:93-95.

112. Piscoya J., Rodriguez Z., Bustamante S., et al. Efficacy and safety of freeze-dried cat’s claw in osteoarthritis of the knee: mechanisms of action of the species Uncaria guianensis. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:442-448.

113. Plaugher G., Cremata E.E., Phillips R.B. A retrospective consecutive case analysis of pretreatment and comparative static radiological parameters following chiropractic adjustments. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1990;13:498-506.

114. Powell F.C., Hanigan W.C., Olivero W.C. A risk/benefit analysis of spinal manipulation therapy for relief of lumbar or cervical pain. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:73-78.

115. Reginster J., Deroisy R., Rovati L., et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001;357:251-256.

116. Reibel D., Greeson J., Brainard G., et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health-related quality of life in a heterogeneous patient population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:183-192.

117. Reinhold T., Witt C.M., Jena S., et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture treatment in patients with osteoarthritis pain. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;9:209-219.

118. Rosenstein E. Topical agents in the treatment of rheumatic disorders. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25:899-918. viii

119. Rydeard R., Leger A., Smith D. Pilates-based therapeutic exercise: effect on subjects with nonspecific chronic low back pain and functional disability: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:472-484.

120. Sajedi F., Alizad V., Alaeddini F., et al. The effect of adding homeopathic treatment to rehabilitation on muscle tone of children with spastic cerebral palsy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14:33-37.

121. Schneider C., Klein P., Stolt P., et al. A homeopathic ointment preparation compared with 1% diclofenac gel for acute symptomatic treatment of tendinopathy. Explore (NY). 2005;1:446-452.

122. Senstad O., Leboeuf-Yde C., Borchgrevink C.F. Side-effects of chiropractic spinal manipulation: types frequency, discomfort and course. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1996;14:50-53.

123. Shekelle P.G. What role for chiropractic in health care? N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1074-1075.

124. Shekelle P.G., Adams A.H., Chassin M.R., et al. Spinal manipulation for low-back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:590-598.

125. Shekelle P.G., Coulter I. Cervical spine manipulation: summary report of a systematic review of the literature and a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10:223-228.

126. Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C., Erro J., et al. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849-856.

127. Siev-Ner I., Gamus D., Lerner-Geva L., et al. Reflexology treatment relieves symptoms of multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled study. Mult Scler. 2003;9:356-361.

128. Sloman R. Relaxation and imagery for anxiety and depression control in community patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25:432-435.

129. Smith A.L., Kolt G.S., McConville J.C. The effect of the Feldenkrais Method on pain and anxiety in people experiencing chronic low back pain. N Z J Physiother. 2001;29:6-14.

130. Smith M., Neubauer D. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic insomnia. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5:28-40.

131. So P.S., Jiang Y., Qin Y. Touch therapies for pain relief in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006535.

132. Targino R.A., Imamura M., Kaziyama H.H.S., et al. A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture added to usual treatment for fibromyalgia. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:582-588.

133. Tarola G.A. Manipulation for the control of back pain and curve progression in patients with skeletally mature idiopathic scoliosis: two cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:253-257.

134. Tovey P. A single-blind trial of reflexology for irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:19-23.

135. Trice J., Pinals R. Dimethyl sulfoxide: a review of its use in the rheumatic disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1985;15:45-60.

136. Valente R., Gibson H. Chiropractic manipulation in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:246-249.

137. Vernon H.T., Humphreys B.K., Hagino C.A. A systematic review of conservative treatments for acute neck pain not due to whiplash. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:443-448.

138. Walker A.F., Bundy R., Hicks S.M., et al. Bromelain reduces mild acute knee pain and improves well-being in a dose-dependent fashion in an open study of otherwise healthy adults. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:681-686.

139. Wang C., Collet J.P., Lau J. The effect of tai chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:493-501.

140. Warnock M., McBean D., Suter A., et al. Effectiveness and safety of Devil’s Claw tablets in patients with general rheumatic disorders. Phytother Res. 2007;21:1228-1233.

141. Watkins G. Music therapy: proposed physiological mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Nurse Spec. 1997;11:43-50.

142. Wegener T., Lupke N- P. Treatment of patients with arthrosis of hip or knee with an aqueous extract of devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens). Phytother Res. 2003;17:1165-1172.

143. Williams D. Psychological and behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia and related syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:649-665.

144. Williams H., Furst D., Dahl S., et al. Double-blind, multicenter controlled trial comparing topical dimethyl sulfoxide and normal saline for treatment of hand ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:308-314.

145. Wu G. Evaluation of the effectiveness of Tai Chi for improving balance and preventing falls in the older population: a review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:746-754.

146. Zwick D., Rochelle A., Choksi A., et al. Evaluation and treatment of balance in the elderly: a review of the efficacy of the Berg Balance Test and Tai Chi Quan. Neuro-Rehabilitation. 2000;15:49-56.