43 Integration of Therapeutic and Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology

The overall five-year survival rates for children younger than 15 years with cancer have increased from less than 60% from 1975 to 1978 to more than 80% from 1999 to 2002.1 Most notable have been improvements in 5-year survival rates for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) now approaching 90%; non-Hodgkin lymphoma similarly approaching 90%; and Wilm tumor, exceeding 90% since the late 1980s. Overall 5-year survival rates most recently reported by the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute approximate 70% overall for primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors and approach 65% to 75% for sarcomas of soft tissue and bone.

Given the profound heterogeneity in diagnosis, clinical presentation, biologic behavior and outcome in primary tumors of the CNS, survival rates for individual tumor types vary considerably. Similarly, for soft-tissue and bone sarcomas, the likelihood of prolonged survival is highly linked to the initial extent of disease. Therefore, reported overall 5-year survival rates should not be considered predictive of cure for all patients with these diseases.2 For example, whereas 5-year survival rates for infants with neuroblastoma are extremely favorable and have been relatively stable at 90% to 95% since the early 1980s, until very recently, improvements in older patients with unfavorable biologic features have not shown the same improvement with current five-year survival rates now approaching only 50%.3

As survival rates differ depending upon the cancer diagnosis, trajectories of illness and patterns of death also differ. For most pediatric oncology diseases, the trajectory from diagnosis to long-term survival or death is characterized by periods of relative stability interspersed with periods of decline or crisis. Symptoms and the trajectory of illness are dependent upon the underlying malignancy.4 Leukemias are the most common type of childhood cancer and tumors of the central nervous system are the most frequent type of solid tumor in children.1 However, specific types of these common childhood malignancies have unique trajectories of illness. For example, a child diagnosed with a brain stem glioma has a poor chance of long-term survival and often presents with multiple neurological deficits, however, a period of symptom improvement may occur with treatment. Unfortunately this period of improvement may be short-lived and is likely followed by exacerbation of symptoms and ultimately death from progressive disease. The timeline from diagnosis to death may be as short as a few months to a couple of years. In contrast, a child with leukemia may initially respond well to treatment and remain in remission. However, if the leukemia returns then the course of illness may be characterized by multiple treatment protocols followed by periods of remission, but may still ultimately end in death due to progressive disease over a period of years. As a further contrast, children undergoing stem cell transplant for a variety of childhood malignancies may die relatively quickly in the trajectory of illness because of sepsis or other side effects of treatment. The palliative care practitioner should be familiar with the symptoms and disease trajectory of the underlying malignancy in order to provide recommendations for effective symptom management.

Despite the impressive record of success in improving survival outcomes, cancer remains the leading cause of death from disease in the pediatric age group. Even cancers such as ALL with high cure rates still account for a significant number of deaths from cancer. Because ALL is the most common cancer of childhood, death related to treatment failure and treatment-related complications in acute leukemia contribute the most to cancer-related mortality statistics in children.1

Whereas the concepts of cure and palliation have historically been somewhat competing objectives, recognition that palliation should not be considered exclusively applicable to end of life is paramount to the childhood cancer journey. Understanding and evaluating interventions to address physical, psychological, social, educational, and spiritual needs in children with cancer from the time of diagnosis onward must be considered.5

The Need for Palliative Care Services in Pediatric Oncology

Approximately 2300 pediatric patients die of cancer in the United States each year.6,7 Most of these patients die of recurrent or progressive disease, and most have been battling their cancers for months to years. For pediatric patients with cancer, cure-directed therapy and palliative care needs go hand in hand from the moment of diagnosis throughout therapy. All patients, even patients with a high likelihood of cure, are likely to suffer multiple symptoms from the point of diagnosis onward. These symptoms include physical side effects from chemotherapy, such as nausea and vomiting, mouth sores and pain, and fevers and hospitalizations, as well as spiritual and psychological malaise. On the other side of the spectrum, many patients who reach the point where there are no known cures for their cancers may continue chemotherapy either as part of an experimental protocol or for palliative purposes.8 Therefore, unlike many other disciplines, pediatric oncology patients are often in need of simultaneous cure-directed and palliative therapies. Effective palliative care services can ease suffering in children with cancer, allowing more hospice referrals and home death, less pain and dyspnea, and better preparation for death compared to families who did not receive palliative care services.9

Despite the clear relationship between palliative care and cancer care for children, many pediatric cancer patients do not receive palliative care services. A survey of institutions that are members of the Children’s Oncology Group revealed that only 58% have palliative care services available for their patients.10 Children with cancer are often receiving intense therapies for extended periods, sometimes years. As a result, they form strong relationships with their oncology team. These relationships can be a great asset as patients and families feel supported by members of the healthcare team who care a great deal about them. However, at times the intensity of the relationship may interfere with a patient’s ability to get appropriate palliative or end of life care. The healthcare team’s members may feel they have failed the patient if cure cannot be offered and may therefore push for cure-directed therapy over comfort care even when the chance of cure is very small.11 In addition, the healthcare team may overestimate the patients’ prognosis in an effort to keep the patient and family hopeful, which affects the families’ ability to make informed decisions about care.6 One study showed that physicians understand that patients have no realistic chance of cure a mean of 101 days before the parents’ recognition.12 Despite the clinicians’ worry, an accurate portrayal of prognosis, even bad, makes families more hopeful, not less.13 Even when parents find the news upsetting, they still derive benefit from hearing the prognosis.14 Additionally, families who know that a child is dying are more likely to spend their end of life period pain-free at home.15

Common symptoms of children with advanced cancers

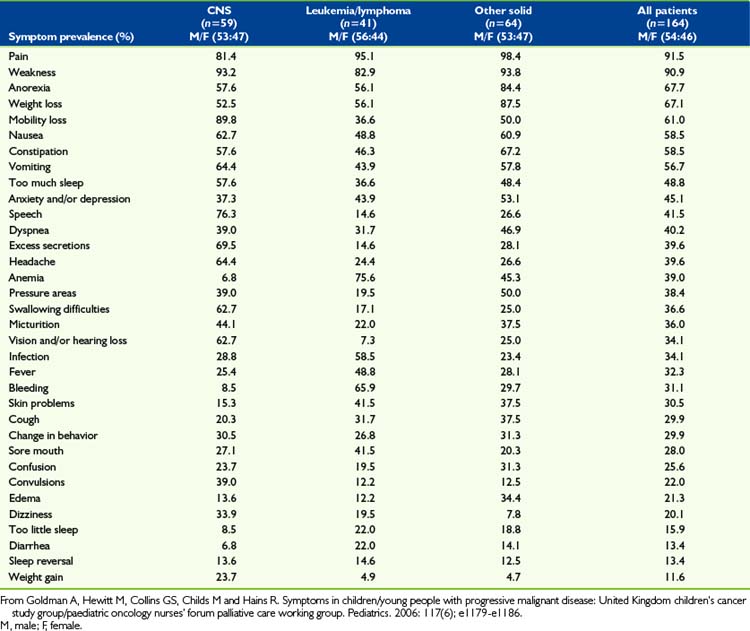

Effective pain and symptom management for children with advanced cancers is dependent upon a sound knowledge of these symptoms.16 Cancer is not unique in the palliative care spectrum in that children often experience multiple symptoms of varying intensities throughout the trajectory of illness. Few studies to date have addressed symptoms or the quality of life experienced by children with advanced cancer or who are dying of cancer.17 Of particular interest are CNS tumors, which are a life-threatening illness with high morbidity and the second-leading cause of cancer deaths in children.18 Children with brain tumors experience more severe symptom distress and treatment-related distress than children with other cancers.19 A variety of symptoms are reported in pediatric patients with advanced cancer. The underlying malignancy impacts the type and severity of symptom distress, however the most common symptoms include pain, fatigue, dyspnea, nausea and vomiting, anxiety, and weight loss and/or cachexia.16,20–23 In addition to these commonly experienced symptoms, children with hematologic malignancies may experience increased bleeding and coagulopathies and children with solid tumors may experience other symptoms related to compression of vital structures by tumor, such as spinal cord compression. An analysis of 164 children with advanced cancers in the last month of life noted that many symptoms are under-recognized and symptoms vary significantly based on the underlying malignancy4 (Table 43-1). Palliative care practitioners must have knowledge of the symptoms associated with the specific pediatric malignancies in order to adequately address symptom distress. Symptom distress is significant for children with advanced cancers and affects their quality of life. Healthcare must not merely be vested in tumor outcomes but must instead address quality of life and functional status outcomes.

Tumor-directed therapy

In one study of bereaved parents, more than one third of the patients had received chemotherapy after it was recognized that the child had no realistic chance of cure. Also, 61% of parents felt their child had suffered as a result of the chemotherapy, and most of the parents would not recommend chemotherapy to other parents of children with cancer without realistic chance of cure. This suggests that in some cases physicians may not fully reveal the potential negative impact of continuing chemotherapy.24 In end of life situations, physicians often use chemotherapy with the goal of reducing symptoms, while many parents believe that the chemotherapy has curative intent.25 Therefore, it is imperative that therapy aimed at shrinking a tumor for symptom relief is clearly identified as such and that the temptation to allow such efforts to be labeled potentially curative, and thereby avoid an honest engagement with end of life, be resisted.

The essential role of hope

None of the above considerations is meant to devalue or undermine the role of hope. Hope is a human state of existence and parents in particular cannot help but harbor hope for their children. Hope is not qualitative; there is no good hope or bad hope. False hope is a misnomer for what should be termed unrealistic expectation. Unlike unrealistic expectations, if a hope is unrealized, it does not result in the negative emotions that carry the power to complicate grief. For parents facing their child’s death, hope often provides them the strength to continue to be mentally and emotionally present to comfort and parent their child. Hope can be described as having three domains: specific future-directed goals, imagining or planning the steps to realize those goals, and believing in one’s own capacity to realize those goals. The degree of hopefulness is the interaction among these three domains.26 An example of this in the context of pediatric oncology may be that of a hospitalized adolescent with advanced cancer who realizes that he will not recover from his illness and is likely to die from his disease, however, he clearly communicates the goal that he would like to attend his high school graduation ceremony in one month. The adolescent and his family meet with the oncology team and the school counselors to discuss how he may participate in the ceremony either in person with his peers or by having a private ceremony, which is developing a plan to meet that goal. They then continue to discuss the ceremony and plan for the events of the day with confidence that the adolescent will be able to participate in the event with specific modifications they have worked out with the school, which is believing in their own capacity to realize the goal. In this context, the family has hope. The phenomenon of hope is a complex and profoundly personal experience for each patient and family.

The paramount hope of parents of children with cancer is for survival. This is by no means the only meaningful hope that parents possess. It is important to help them to identify the other meaningful things for which they hope such as the minimization of suffering, the ability of their child to interact with loved ones, and their child’s ability to feel joy or participation in a meaningful experience as above. The healthcare team often struggles with balancing hope with providing accurate information about the child’s disease.27 The healthcare team should not undermine the family’s hope for a miracle but rather provide guidance for the family to identify realistic goals and other meaningful hopes. Providing families with accurate prognostic information and awareness building resources may help them have a healthier bereavement process.13

Preparations for end of life

Part of the process of maintaining hope at the end of life is control over the process for patients and their families. Frank discussions with families when cure becomes extremely unlikely allow families and children to have some control. For example, choosing the location of death has been shown to help families feel prepared for their child’s death.28 Families who know their children are likely to die can make educated decisions about advanced care planning, or about further therapies.

In addition, when families are prepared, they are more likely to be able to talk to their children about the fact that they are likely to die. Children with cancer tend to be very savvy about their conditions, and often surprise their families and caregivers with their insight into their care plans and desire to be involved with their treatment decisions. A study of 20 children and adolescents with refractory cancers showed that children understood they were involved in end of life decisions and were capable of participating in those discussions. This study also found that children, as well as their parents, often cited altruism as a factor in their decision making about care.25 In addition, another study found that parents were actually less upset about receiving news about their child’s cancer and treatment when their children were present for the conversation.14 Finally, in a follow-up study of parents whose child died of cancer, no parents who talked to their children about death had regrets, while 27% of those who had not had the discussion did have regrets.29

Phase I Clinical Trials in the Context of Palliative Care

As parents and children make the emotional and intellectual transition from a therapeutic environment centered on curative intent to one where quality of life and management of symptoms dominate, they often become paralyzed by a feeling that they are giving up. This false perception is rooted in a number of factors, including an unrealistic belief in the power of modern medicine to control the course of disease, the feeling that the hope for survival is the only sustaining hope, and parental fear that they are ill-equipped to help their child. In many cases, the transition is complicated by a sense of suddenness if the provider and family have previously collaborated to avoid the painful acknowledgment of the potential for a fatal outcome. This time of transition is also when many families are offered enrollment in Phase I clinical trials because eligibility for such trials stipulates that no known curative therapies be available. Given the difficulty of this transition and the vulnerability of parents in this position, an inherent trap exists in the presentation of Phase I clinical trial; they can be seen as a continuation of cure-oriented therapy using a new drug. A study of parental reasons for enrollment in a Phase I study showed that two thirds believed that the alternative of no tumor-directed treatment was unacceptable.30 This perception implies an expectation of therapeutic benefit. It is incumbent upon the clinical researcher to clearly describe the nature of Phase I clinical trials as seeking to determine the safety of new compounds, rather than offering a realistic expectation of disease response.

As has been shown, dying children tend to have higher symptom burdens and a greater need for palliative care.31 Thus, Phase I clinical research virtually always takes place in a context of palliative care. However, it is important to distinguish palliative therapies intended to reduce tumor burden in an attempt to relieve symptoms from the Phase I clinical trials. Novel agents being given in a research context should not be used with a palliative intent. One large meta-analysis found an objective response rate of only 9.6% in 69 trials.32 Indeed, the potential exists to induce bothersome symptoms and thereby detrimentally affect quality of life, the antithesis of the goal of the end of life period. The risk of inducing suffering must therefore be carefully weighed in the decision to pursue Phase I clinical trials in each individual case.

However, an admonition to avoid creating an expectation of disease response does not preclude that the patient and family may derive benefit from participation in a clinical research trial. Indeed, objective tumor response is not a good surrogate measure of direct benefit from participation in a trial. In a minority of cases, disease stabilization can provide relief from symptoms and prolong good quality of life. A study of 16 Phase I trials conducted at the NCI found a disease stabilization rate of 17%, although stabilization was modestly defined as completing three cycles of therapy without disease progression.33 Other potential benefits include the strengthening of hope and the altruistic opportunity to help other children and thereby derive some meaning from their ordeal. In a study of parental decision making around Phase I trials, the provision life-prolonging treatment to allow for the possibility of a new therapy, having more time with their child, the hope for a cure and/or miracle, and the desire to help other children were identified as operative factors; the two main themes represented by these factors are hope and altruism.25

A common consequence of trying a new medicine, as families see it, is bolstering hope for survival. This is not unhealthy as long as efforts are taken to differentiate such a hope from an unrealistic expectation for effectiveness. When properly framed, such hope can free parents from the paralytic effects of despair and allow them to actively pursue other quality of life oriented hopes and goals. The mantra hope for the best and plan for the worst places the proper perspective on the events of the end of life experience. “There is nothing more we can do” should be reframed to include the idea that even though the disease is unlikely to be cured, there may be other realistic goals for which the patient and family should strive.27

Altruism is a commonly cited reason for participation in clinical trials. A study of informed consent conferences for pediatric Phase I trials found that two-thirds of consent conferences contained broad discourse on the potential benefit to others of participation, but it was raised by the physician in 80% of the cases. There was no correlation between the discussion of altruistic motives and the rate of participation.34 Another study of the personality characteristics of volunteers for clinical studies found a higher than normal scoring for altruism.35 When adolescents were studied, the qualitative data suggested that a concern for others is more prevalent in patients facing graver threats to their health.36 Therefore, while altruism may not be a driving factor in the decision-making process, there is abundant anecdotal evidence for parents and adolescents who verbalize comfort in the concept of helping other children. In this sense, adherence to an altruistic motive, among others, can represent a benefit to participation in Phase I trials in that it allows family’s to provide a context of meaning for their suffering.

The transition phase from cure directed to palliative therapy is a difficult one for providers, patients and families. Offering Phase I clinical trials at this juncture can be done in a just and noncoercive way that provides benefit to the child and family without setting up an expectation for tumor response. Further, given the essential nature of hope at this time, it is necessary to lead the family in a discussion to discover their perceptions of the elements of a quality-filled life; these things should become objects of hope.37 The means to achieve these hopes and goals lies within palliative care and hospice care at the end of life. Therefore, the transition period where Phase I therapies are often discussed makes a natural place for the discussion of palliative and hospice care if it has not already been addressed. Indeed, an argument can be made that the responsible discussion of Phase I therapy should always be preceded by or include a discussion of palliative or hospice care.

Symptoms and Suffering of Children with Cancer

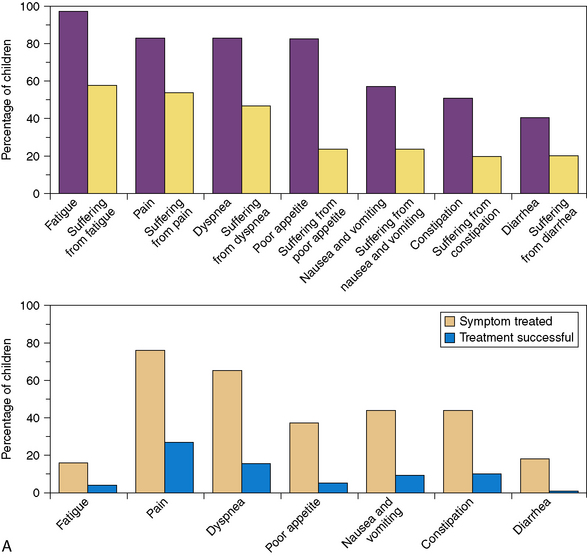

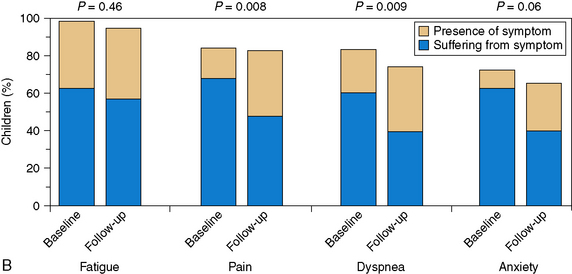

A pivotal study published in 2000 revealed that the majority of children with cancer suffer “a lot” or “a great deal” in their last month of life. Physicians were much less likely to report symptoms compared with parents, and treatments for symptoms were often not deemed effective.38 The most frequent symptoms reported were fatigue, pain, dyspnea, poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea (Fig. 43-1, A). A follow-up study in 2008 showed that with the initiation of the principles of palliative care earlier in the disease process, children experienced less suffering with regard to many of these prevalent symptoms and parents felt more prepared for the trajectory of the end of life process9 (Fig. 43-1, B). In a more recent study of children with cancer in the last day and last week of life, parents reported similar distressing symptoms by answering open-ended questions. In this case, the most frequently reported distressing symptoms included change in behavior, breathing changes, pain, change in appearance, weakness and fatigue, and change in heart rate. These symptoms were the same at a week and a day before death, though the frequency changed over the two time points. The interventions that helped the most were not usually disease-specific, but rather related to the medical team being present, and having good and open communication.31 The effectiveness of symptoms control at the end of life can have lasting repercussions for parents who watch their children die. In one study, more than half of parents whose children had pain at the end of life or a difficult moment of death were still affected by that memory four to nine years later.39

Integrative therapies as palliative care in children with cancer

Integrative therapy is often used by pediatric oncology patients, generally in addition to cure-directed conventional therapies, and often for supportive care purposes. Studies have reported 59% to 84% of children with cancer use integrative therapies.40,41 Many of the nation’s top pediatric hospitals have created centers for integrative medicine practice and research, particularly for use by pediatric cancer patients.

Of the integrative therapies, massage is one of the more popular with about 30% of children in general40 and 60% of children with cancer42 reporting use. There are limited studies of massage in children in general, and only two studies published on massage therapy in pediatric oncology patients. However, the studies consistently demonstrate improvements in anxiety in patients who receive massage, as well as some suggestions of improvement in distress, pain, tension, discomfort, and mood, indicating that massage can be helpful for palliation of symptoms in children with cancer.43–46

Acupuncture is also widely used in pediatric oncology patients. While evidence in pediatric conditions is somewhat lacking due to a paucity of well-designed clinical trials,47 there is evidence of efficacy in adult cancer patients with symptoms such as nausea and vomiting,48,49 pain, fatigue, anxiety, and insomnia,50,51 which are all symptoms that are equally burdensome to pediatric oncology patients. In addition, acupuncture has been shown to be well tolerated in children52,53 and has been shown to help some children, particularly with pain management.54–56 Acupuncture has been trialed in one pediatric oncology study of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting where it was found to significantly decrease need for rescue nausea medications as well as vomiting episodes.57 Very few adverse events have been noted.

Research needs and opportunities

While the seamless integration of clinical research with clinical care in the approach to children with cancer has had a marked impact on improving the chances for cure, the time has come to provide appropriate focus and to apply similar rigor in the design and conduct of controlled clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of interventions to improve the quality of life during all phases of the cancer experience. Longitudinal investigations of the outcome of children and the associated acute and late sequelae of cancer and its therapy have led to modifications and refinements of subsequent treatment approaches.58–60 Likewise, both retrospective and prospective studies using patient and family self-reported outcomes must be developed to assess efficacy of symptom management and prevention; interventions for social, psychological, and spiritual health; and end of life and bereavement care. These data can be used to provide a sound rationale for the construction of prospective intervention studies in order to improve quality of life for patients and families, including the minority for whom cure is not possible. Such information is also critical to the development of education and training materials and programs for all levels of caregivers and trainees. It will help to assure that there are no missed opportunities for patients and families if palliative care is conceptualized as integral to all the services provided to a child with cancer and his or her family. It should also be seen as an integral domain with respect to interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary clinical research for which the pediatric oncology community has most definitely demonstrated proof of principle.

The fact that families of children with cancer are fully capable and open to the dual goals of concurrently providing disease-directed and comfort care creates a profound opportunity, and a mandate for early integrated palliative care, rather than an unfortunate and unexpected end result of unsuccessful attempts to provide cure.25,61,62 The early development of collaborative partnerships among parents, patients, and caregivers has been critical to the success of therapeutic and non-therapeutic research studies in pediatric oncology. These same relationships can and should greatly facilitate the information, trust generation, and consent process for therapeutic research in palliation as well. Meaningful and generally sustainable bonds among caregivers and patients and families can also be effectively used to their full advantage in investigating appropriate interventions at the end of life and even effective supportive measures during bereavement.

1 United States Department of Health and Human Services. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence SEER 9 RegsLimited-Use. Nov 27Sub (1973–2005) Worldwide website: www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed Nov.25, 2008

2 Steliarova-Foucher E., Siller C., Lacour B., Kaatsch P. International Classification of Childhood Cancer. ed 3. Cancer. 103:2005: 1457-1467.

3 Matthay K.K., Reynolds C.P., Seeger R.C., et al. Long term results for children with neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13-cis-retinoic acid: a Children’s Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009.

4 Goldman A., Hewitt M., Collins G.S., Childs M., Hains R. Symptoms in children/young people with progressive malignant disease: United Kingdom children’s cancer study group/paediatric oncology nurses’ forum palliative care working group. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1179-e1186.

5 Harris M.B. Palliative care in children with cancer: which child and when? J Natl Cancer Inst Monograph. 2004;32:144-149.

6 Field M. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

7 Klausner R. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975–1995. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 1999.

8 Bluebond-Langner M., Belasco J.B., Goldman A., et al. Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2414-2419.

9 Wolfe J., Hammel J.F., Edwards K.E., Duncan J., Comeau M., Breyer J., Aldridge S.A., Grier H.E., Berde C., Dussel V., Weeks J.C. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717-1723.

10 Johnston D.L., Nagel K., Friedman D.L., et al. Availability and use of palliative care and end-of-life services for pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4646-4650.

11 Mack J.W., Cook E.F., Wolfe J., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1357-1362.

12 Wolfe J., Klar N., Grier H.E., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284:2469-2475.

13 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Cook E.F., et al. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5636-5642.

14 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Grier H.E., et al. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265-5270.

15 Surkan P.J., Dickman P.W., Steineck G., Onelov E., Kreicbergs U. Home care of a child dying of a malignancy and parental awareness of a child’s impending death. Palliat Med. 2006;20(3):161-169.

16 Woodgate R.L., Degner L.F., Yanofsky R. A different perspective to approaching cancer symptoms in children. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(3):800-817.

17 Hinds P.S., Billups C.A., Cao X., Guttuso J.S., Burghen E.A., West N., et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents at the time of diagnosis with osteosarcoma or acute myeloid leukemia. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009. in press

18 Lee D.P., Skolnik J.M., Adamson P.C. Pediatric phase I trials in oncology: An analysis of study conduct efficiency. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8341-8351.

19 Meeske K., Katz E.R., Palmer S.N., Burwinkle T., Varni J.W. Parent proxy-reported health-related quality of life and fatigue in pediatric patients diagnosed with brain tumors and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2004;101(9):2116-2125.

20 Hinds P., Quargnenti A.G., Wentz T.J. Measuring symptom distress in adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1992;9(2):84-86.

21 Hongo T., Watanabe C., Okada S., Inoue N., Yajima S., Fuji Y., et al. Analysis of the circumstances at the end of life in children with cancer: symptoms, suffering and acceptance. Pediatr Int. 2003;45:60-64.

22 Prichard M., Burghen E., Srivastava D.K., Okuma J., Anderson L., Powell B., et al. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1301-e1309.

23 Houlahan K.E., Branowicki P.A., Mack J.W., Dinning C., McCabe M. Can end of life care for the pediatric patient suffering with escalating and intractable symptoms be improved? J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;23(1):45-51.

24 Mack J.W., Joffe S., Hilden J.M., et al. Parents’ views of cancer-directed therapy for children with no realistic chance for cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4759-4764.

25 Hinds P.S., Drew D., Oakes L.L., et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146-9154.

26 Snyder C.R. Handbook of hope: theories, measures & applications. San Diego: Academic Press, 2000.

27 Tulsky J.A. Beyond advanced directives: the importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA. 2005;294:359-365.

28 Dussel V., Kreicbergs U., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., Moore C., Turner B.G., Weeks J.C., Wolfe J. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):33-43.

29 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdóttir U., Onelöv E., Henter J.I., Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1175-1186.

30 Deatrick J.A., Angst D.B., Moore C. Parents’ views of their children’s participation in phase I oncology clinical trials. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2002;19(4):114-121.

31 Pritchard M., Burghen E., Srivastava D.K., et al. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1301-e1309.

32 Lee D.P., Skolnik J.M., Adamson P.C. Pediatric phase I trials in oncology: an analysis of study conduct efficiency. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8431-8441.

33 Kim A., Fox E., Warren K., et al. Characteristics and outcome of pediatric patients enrolled in phase I oncology trials. Oncologist. 2008;13(6):679-689.

34 Simon C., Eder M., Kodish E., Siminoff L. Altruistic discourse in the informed consent process for childhood cancer clinical trials. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6(5):40-47.

35 Almeida L., Falcao A., Vaz-da-Silva M., Coelho R., Albino-Teixeira A., Soares-da-Silva P. Personality characteristics of volunteers in Phase 1 studies and likelihood of reporting adverse events. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(7):340-348.

36 Hinds P.S. The hopes and wishes of adolescents with cancer and the nursing care that helps. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(5):927-934.

37 Clayton J.M., Butow P.N., Arnold R.M., et al. Fostering coping and nurturing hope when discussing the future with terminally ill cancer patients and their caregivers. Cancer. 2005;103:1965-1975.

38 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:326-333.

39 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdóttir U., Onelöv E., Björk O., Steineck G., Henter J.I. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9162-9171.

40 Post-White J., Fitzgerald M., Hageness S., Sencer S.F. Complementary and alternative medicine use in children with cancer and general and specialty pediatrics. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2009;26(1):7-15.

41 Kelly K.M. Complementary and alternative medicinal therapies for children with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2041-2046.

42 McLean T.W., Kemper K.J. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies in pediatric oncology patients. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4(1):40-45.

43 Post-White J., Fitzgerald M., Savik K., Hooke M.C., Hannahan A.B., Sencer S.F. Massage therapy for children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2009;26(1):16-28.

44 Phipps S., Dunavant M., Gray E., Rai S.N. Massage therapy in children undergoing hematopoetic stem cell transplantation: results of a pilot trial. J Cancer Integrative Med. 2005;3(2):62-70.

45 Beider S., Moyer C.A. Randomized controlled trials of pediatric massage: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4(1):23-34.

46 Suresh S., Wang S., Porfyris S., Kamasinski-Sol R., Steinhorn D.M. Massage therapy in outpatient pediatric chronic pain patients: do they facilitate significant reductions in levels of distress, pain, tension, discomfort, and mood alterations? Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18(9):884-887.

47 Gold J.I., Nicolaou C.D., Belmont K.A., Katz A.R., Benaron D.M., Yu W. Pediatric acupuncture: a review of clinical research. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008. Jan 10

48 Melchart D., Linde K., Fischer P., Berman B., White A., Vickers A., Allais G. Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2001. CD001218

49 Ernst E. Acupuncture: what does the most reliable evidence tell us? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):709-714.

50 Ladas E.J., Post-White J., Hawks R., Taromina K. Evidence for symptom management in the child with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28(9):601-615.

51 Lu W., Dean-Clower E., Doherty-Gilman A., Rosenthal D.S. The value of acupuncture in cancer care. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22(4):631-648.

52 Kemper K.J., Sarah R., Silver-Highfield E., Xiarhos E., Barnes L., Berde C. On pins and needles? Pediatric pain patients’ experience with acupuncture. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 2):941-947.

53 Wu S., Sapru A., Stewart M.A., Milet M.J., Hudes M., Livermore L.F., Flori H.R. Using acupuncture for acute pain in hospitalized children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(3):291-296.

54 Kundu A., Berman B. Acupuncture for pediatric pain and symptom management. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(6):885-889.

55 Tsao J.C., Meldrum M., Bursch B., Jacob M.C., Kim S.C., Zeltzer L.K. Treatment expectations for CAM interventions in pediatric chronic pain patients and their parents. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2(4):521-527.

56 Lin Y.C., Lee A.C., Kemper K.J., Berde C.B. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatric pain management service: a survey. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):452-458.

57 Gottschling S., Reindl T.K., Meyer S., Berrang J., Henze G., Graeber S., Ong M.F., Graf N. Acupuncture to alleviate chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric oncology—a randomized multicenter crossover pilot trial. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220(6):365-370.

58 Friedman D.L., Meadows A.T. Late effects of childhood cancer therapy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(5):1083-1106.

59 Institute of Medicine. Childhood cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004.

60 Green D.M. Late effects of treatment for cancer during childhood and adolescence. Curr Probe Cancer. 2003;27:127-142.

61 Wolfe J., Friebert S., Hildon J. Caring for children with advanced cancer: integrating palliative care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:1043-1062.

62 Hurwitz C.A., Duncan J., Wolfe J. Caring for the child with cancer at the close of life. JAMA. 2004;292:2141-2149.

63 Stutzer C. Pediatric oncology palliative care in British Columbia. BC Provincial Pediatric Hematology Oncology Network Newsletter. 3;2004: 1-4. Fall