Chapter 8. Integrating performance: linking healthcare domains

Marc Berg, Wim Schellekens and Cé Bergen

Introduction

The US Institute of Medicine reports ‘To Err is Human’ and ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm’ have had repercussions throughout Western medicine (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America, 2000 and Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America, 2001). Given the resources spent and the qualifications of its professionals, the reports argue, there is a chasm between what the overall quality delivered by the system should be and what it actually is. The US healthcare system is fragmented and ‘wasteful’. Any journey through it includes many ‘steps and handoffs that slow down the care process and decrease rather than improve safety’ (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001:28).

As the earlier chapters in this book also testify, the reports’ insights are applicable to most Western countries, and the demands on the healthcare system in the near future will only increase. The safety, effectiveness, patient centredness and timeliness of care have to be improved, while keeping costs from rising further. How can we align these targets? Small, local improvement initiatives will not do the job. Nor will large, sweeping ‘quality-improvement initiatives’ have a lasting impact if the improvements do not become embedded in a more fundamental redesign of the operations of healthcare work.

In this chapter, we take up this challenge. We do not discuss the (country-specific) payment and regulatory systems that stimulate or obstruct change at the level of the care process. We will, rather, describe a series of less country-specific, interrelated design principles that depict how healthcare delivery could be organised. This vision is futuristic: no healthcare practice has fully achieved it. Yet it is simultaneously realistic, in that it builds upon elements that are broadly accepted and proven – both theoretically and practically.

The design principles pivot around the notion of care programs: work routines based on multidisciplinary protocols that encompass tasks, decision criteria and work procedures for the care professionals involved in the care of a patient category. Such care programs touch upon all levels of the organisation: operational, tactical and strategic. On the operational level, they streamline work processes and, when designed properly, increase efficiency, patient safety, effectiveness and patient centredness simultaneously. Yet these operational characteristics may ultimately not be the most important ones. On the tactical and strategic level, we will argue, care programs will be the organisational building blocks around which the healthcare organisations of the future will be shaped. Care programs will bring together teams of professionals producing optimal quality care for patients with a given condition or problem. In line with current trends in healthcare financing and regulation, the teams running these care programs will become self-steering – responsible for their own clinical and financial results.

Integrating professional and organisational quality

In current healthcare practices, many individuals are working to improve the different dimensions of ‘quality’. Through guidelines and audits, professionals attempt to enhance the evidence-based nature of their work (Grol 2000). Quality managers organise the certification or accreditation of their organisation, information managers develop the information technology infrastructure, and unit managers worry about the optimal planning of scarce resources such as personnel and expensive technologies (Klazinga 2000, Berg 2004). Usually, however, these activities are organisationally separate and the responsible individuals, including professionals, information managers and quality managers, interact more with their peers in other organisations than with each other (Berwick 1998). In addition, they focus on different quality dimensions: professionals mainly focus on effectiveness and safety, line managers on efficiency, and so forth. At heart, the deepest dividing line runs between the professionals ‘owning’ and improving the content of healthcare work and the managers ‘owning’ and improving the organisation of that work.

To overcome the quality chasm, these separate activities have to become integrated. This is partly a matter of organisation: rethinking the composition of a project’s steering group, for example, or organising ‘integrated quality meetings’ at board level (Leape et al 2000, Murray & Berwick 2003). Yet the true integration of these activities requires a conceptual innovation: a vision on how these different activities are part and parcel of the same enterprise. To overcome the quality chasm, to improve the different dimensions of ‘quality’ simultaneously, we need to join state-of-the-art insights from different fields into a single integrated approach. In other words, we need to learn to simultaneously think about content and organisation of healthcare work for radical change to become possible.

Standardisation – creating care programs

The heart of fundamental care delivery innovation lies in the standardisation of care into ‘care programs’ (see Figure 8.1). Currently, the archetypal mode of organising healthcare delivery is the ad hoc step-by-step approach. Since every patient trajectory is unpredictable, the care professional requires the freedom to ‘pick’ what this unique patient requires next from the palette of their professional knowledge base. Every patient follows his own trajectory and in these trajectories each next step is decided upon the step before (de Vries & Hiddema 2001, Strauss et al 1985).

|

| Figure 8.1 |

One-hundred years ago, before the times of medical specialisation, physicians could handle most of what any patient could bring to their attention, and few diagnostic and therapeutic options were available (Howell 1989). At that time, the step-by-step mode of care delivery was both patient centred and efficient. In our times, however, the theory and practice of medicine have become highly complex. Healthcare institutions are populated by many different professions and specialists, handling patients that often require the attention of several of these. Yet most of our care delivery is still organised according to this archetypal form. Every next step (e.g. a surgical operation) is only conceived and planned at the completion of the previous step (e.g. obtaining diagnostic test results), resulting in frequent waits and, more often than not, very ad hoc and variably shaped patient trajectories. The result is a care process that is fragmented (not patient centred), unsafe and inefficient (see Claridge & Cook, Chapter 4).

Yet is patient care not in principle organised this way because individual patients have individual histories and needs (Strauss et al 1985, Timmermans & Berg 2003)? The individual trajectory of a patient suffering from heart failure, for example, is indeed unpredictable. A patient’s personal and medical history will shape his and his physician’s preferences in unique ways, and symptoms and reactions to therapeutic interventions never quite behave according to textbook definitions. Yet at an aggregated level, much of this individual variation disappears. For the category of heart failure patients, the steps that are mostly taken, or that should be taken, can be predicted.

For the major categories of patients that an organisation deals with care programs can be developed. As stated, care programs are work routines based upon multidisciplinary protocols that encompass tasks, decision criteria and work procedures for the care professionals involved in the care of such a patient category (see Box 8.1). Care programs can be limited to a hospital or a department, but they should ideally include all providers having a role in the care of a category of patients. The different professionals jointly develop these protocols, drawing upon evidence-based guidelines wherever possible.

Box 8.1

The term ‘care program’ is used to emphasise the patient-centred organisationof care around the major patient categories the organisation(s) involved deals with. We do not use the term ‘critical pathway’, or ‘carepath’ because these terms usually refer to a detailed protocol, sometimes used in the form of a time-oriented recording sheet. Usually, ‘critical carepaths’ are predominantly about increased effectiveness, although sometimes an increase in efficiency (such as through reducing length of stay) is included. Also, the ‘critical pathway’ literature is largely nursing oriented, while we emphasise the multidisciplinary nature of the care program.

A care program is typified by the integration of activities between disciplines, professions, departments and, in the case of a multi-organisational care path, organisations. Also, care programs are about tackling professional and organisational quality simultaneously: optimising effectiveness, efficiency, patient centredness and safety through integrating (not running side by side) professional and organisational ‘best practices’. Finally, with the notion of ‘care program’ we explicitly refer to both the operational and the tactical/strategic impact of redesigning care processes in such a way.

At the same time, a terminological battle is meaningless: much current ‘carepath’ work comes close to what we address in this paper.

Most of the benefits of care programs are well known: care delivery becomes more evidence based, and colleagues, patients and payers know what care to expect. Time after time, it has been shown that following smart guidelines meticulously yet non-dogmatically saves lives (Berenholtz et al 2004, Luthi et al 2003, Schiele et al 2005). Also, care programs afford safer care. Every safety expert knows that there is nothing more lethal than unwarranted variation in critical processes. Uncontrolled variation obstructs flow, unnecessarily burdens the cognitive processes of those involved in the process check and prohibits learning (because the process outcomes cannot be compared to each other) (Carroll & Rudolph 2006, McManus et al 2003, Rozich et al 2004).

Care programs also afford a reduction of coordination work. Working step-by-step requires each next step to be organised and planned anew, including all the ad hoc phone calls and form filling that comes with that. In organisations that work under pressures of time and resources (and most healthcare organisations do), this implies stress and loss of professionals’ and patients’ time. With care programs, the sequence of activities to pursue and professionals to see is already established. Rather than establishing this anew every time a patient comes in with ‘heart failure’, this care program is made beforehand by the professionals involved. Since everyone knows what to expect in the next, and previous, steps, coordination work is reduced (Mintzberg 1979, Timmermans & Berg 2003).

Finally, well-designed care programs are patient friendly. Those who mistake this call for standardisation for a call to quench the ‘art’ of medicine cannot be more mistaken. There is nothing ‘patient friendly’ in unnecessary waiting times and unnecessary safety risks. There is, on the other hand, nothing more patient friendly than a well-organised, smooth trajectory, in which everyone involved knows what is expected of them, is optimally informed, and can give their full attention to the patient (Millenson 1997).

For this to work, it is crucial that care programs are not just written guidelines. They should be concretely ‘anchored’ in the organisation through working arrangements between professionals and departments, special outpatient and inpatient facilities, the information technologies and forms used, material affordances and constraints, and so forth. For example, charts may be prestructured to indicate the steps to take next, or an outpatient clinic designed for optimal breast cancer care may be put in place. Likewise, the sterilised instrument baskets used in operating rooms can be standardised to ensure that the right tools for the job will be at hand, and checklists can be put in place that must be followed before a high-risk procedure is started (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2000, Norman 1988, Parker 1997). (See Box 8.3 for the importance of ‘flexible standardisation’ in making care programs work.)

Pause for reflection

The call for more ‘standardisation’ in healthcare practice is not new. In what forms has this call been heard in earlier years? Why has it been mostly ignored, until recently? What are the factors that might make it heard this time around.

Restructuring and delegating tasks

When developing care programs, the individual tasks, decision moments and work procedures should be critically reconsidered as to their organisational safety, patient centredness and efficiency. Can blood tests not be performed on the same day as the next visit? Can the variety in surgical techniques used by different surgeons be limited (Bell et al 2006, Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2000, Dy et al 2003)? This redesign starts by considering the four different components that constitute every care program: triage, intake, the core activities of the care program, and follow-up. Not all care programs will require these steps to be separated, but any care program requires:

▪ the decision whether the patient belongs here (triage)

▪ the selection of the optimal care program (including (further) diagnostic workup) (intake)

▪ a limited set of core diagnostic and/or therapeutic activities (core)

▪ follow-up activities (follow-up).

Triage and intake are often necessarily entwined. In emergency situations the intake and the core activities are often inseparable. In chronic care the ‘core’ of the care program can extend for years. In acute care situations it may last only briefly. In general, however, disentangling these components helps in designing subtasks that can be delegated, or executed in a more effective, patient-friendly and efficient way. In current practices, every individual patient encounter seems unique because every patient comes to that encounter through a different route, with different diagnostic and therapeutic activities being done. In current healthcare practices, every single patient encounter is unique partially because there is no conscious attempt to streamline these encounters. By separating ‘triage’ and ‘intake’, and by organising the care delivery process accordingly, patient flows become more predictable. Patients remain unique, but not in the sense of varyingly incomplete diagnostic histories, or large differences in therapeutic steps already taken.

Often, (specialised) nurses can do (part of the) intake, so that the physician is freed from tasks that do not require their expertise. Ensuring a complete work-up before the consultation with a medical specialist, for example, can save many unnecessary outpatient visits. Given shortages in qualified personnel, such a redistribution of tasks is essential to managing the increasing demand for care. Retinopathy screening for diabetes patients, medication optimisation in heart failure patients (see Box 8.2) and glaucoma treatment are some of the examples where a redistribution of tasks between doctors, nurses and/or paramedics can provide optimal care for more patients (Johnson et al 2003).

Box 8.2

In the Martini Hospital in Groningen, the Netherlands, patients suffering from heart failure used to occupy some 40% of the hospital’s cardiology beds. Most of these patients had been admitted because their conditions had slowly deteriorated to the point that admission was necessary. They had usually been under ‘standard’ care: regular consultations with the cardiologist or visits to the general practitioner had not prevented their hearts from decompensating. A combination of factors appeared to be at work: primarily suboptimal medication (Bouvy et al 2003), but also poor lifestyle education and poor compliance of patients with the medication and lifestyle rules. Working under time pressure, and having many other patients with acutely pressing problems, cardiologists and practitioners often spent too little time on medication finetuning and lifestyle education.

Nowadays, patients with heart failure visit a special outpatient clinic, run by cardiologists and nurse practitioners. After an initial joint consultation with a cardiologist and nurse, the nurse, supported by a computerised decision-support tool, monitors the patient’s blood pressure, weight, renal function and so forth, and finetunes the medication prescribed by the cardiologist over some five to six sessions. Based upon evidence-based guidelines, the computer similarly helps the nurse to counsel the patient on required lifestyle changes. The cardiologist only comes into play during the first session (unless unexpected reactions to treatment, for example, lead the nurse to consult the cardiologist on an ad hoc basis) (de Vries et al 2002).

In this way, the outpatient cardiology clinic has liberated 6–8% of overall capacity, because patients are now handled by the nurse practitioner, and because patients suffer less from unnecessary deterioration of their condition. Overall, 80% of heart failure patients now receive optimal medication treatment, the average patient’s ejection fraction (a core effectiveness indicator) has improved by 60%, and heart failure readmissions have reduced by 30%. The software application is now in use in over 40 Dutch hospitals (de Vries et al 2002).

Care programs and restructuring and delegating tasks are mutually dependent (see the arrows in Figure 8.1). On the one hand, restructuring and delegating tasks makes standardisation feasible: without this, one could not achieve as much quality gain with care programs. Again, multiple dimensions can now be optimised simultaneously: efficiency (optimal use of expensive capacity), timeliness (reduced throughput times), effectiveness (appropriate combinations of expertise at the right time and place) and patient centredness (a care program organises the care delivery resources around the patient rather than vice versa).

On the other hand, care programs are a necessary element of redesign and task delegation. Care programs can ensure both (a) the quality of the work delivered by the different care professionals involved and (b) the coordination of their work tasks. Both require standardisation of decision criteria (which patients may be handled by the nurse; what to do in case of doubt), data (what to register, terminology to use) and work procedures (what actions that should be done by whom). In the example of heart failure care (see Box 8.2), the nurse practitioner is supported by simple computer-based decision support systems that have been made by the physicians who hold final responsibility. In addition, the chance of errors is minimised: whenever uncertainty arises, the patient drops out of the ‘standard’ category, and is seen by a cardiologist immediately.

Resource planning and flow optimisation

The current step-by-step approach in care delivery comes with a significant level of autonomy of the individual professionals, departments or organisations ‘processing’ each step. The operating room, outpatient clinics, hospital pharmacy, radiology and pathology departments generally run ‘their own ship’, having their own lines of accountability with organisational management. Making links between units (such as booking a CT scan or requesting a consultation) take place on an ad hoc basis.

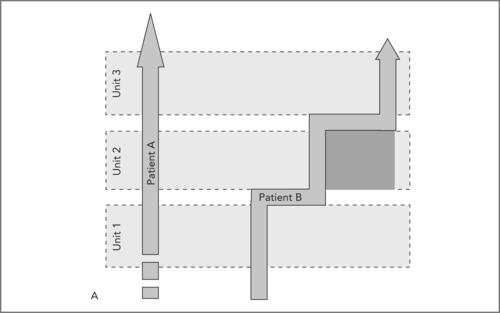

When qualified staff, expensive technologies, investigation rooms and beds are abundant, the patient’s trajectory through such a loosely coupled system may be smooth (see Figure 8.2A, Patient A). When such resources are not abundant, it is unlikely that they are available when the patient’s care demands it. As a result, the patient’s trajectory will look like Patient B (see Figure 8.2A): after having waited for a first appointment, the patient waits for a slot in the diagnostic facility, then returns to the consultant and waits for a place in the operating room schedule. For the patient and the care institution(s), time is wasted, during which unnecessary coordination work has to be performed and additional costs are incurred.

|

| Figure 8.2A |

In Figure 8.2A the straight trajectory of Patient A signifies a smooth handling of the patient, including at the interfaces between units (e.g. outpatient clinic, diagnostic facilities, inpatient ward). The shaded box below the Patient B trajectory is the time lost due to waiting times between Units 2 and 3. Such waiting times are often not noticed at the level of the management of the whole organisation, since units generally each report about their own performance, not about the performance of the ‘transfer’ moments between units.

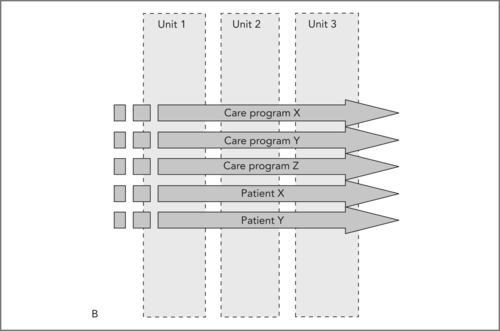

In Figure 8.2B the care programs X, Y, Z are now leading; the organisation and internal management of the units is now dependent on the care program that the organisation has decided upon. The smooth arrows indicate smooth handling. ‘Patients X and Y’ indicate that not all patients fit care programs; these patients can and should also be anticipated and planned for separately. As the diagram indicates, both types of patients can be managed in parallel.

|

| Figure 8.2B |

Through care programs, optimising the planning of scarce resources becomes possible. When it is made clear what the standard paths are for the majority of patients, the resources required for those care programs become apparent. By organising an outpatient clinic for heart failure patients (see Box 8.3), for example, and knowing the average number of new patients visiting the clinic, the number of nurse practitioners and consultancy rooms can be planned in advance. If, for example, 25% of cases require additional cardiological testing, this can be planned for as well.

Box 8.3

The term ‘standardisation’ is often associated with ‘Taylorism’ or ‘managed care’, and thus carries many predominantly negative associations: bureaucracy, over-regulation, standardisation for standardisation’s sake (Wiener 2000). Yet as we emphasise here, standardisation – of core steps in a care program, of techniques used, of communication patterns – is a prerequisite for the ambitions set by the Institute of Medicine’s reports.

Importantly, however, standardisation should remain flexible. The care program is no ‘assembly line’. At each individual step, the care professional can choose to not take the next step planned, and plan an alternative action in the traditional step-by-step approach. In addition, standardisation should not be pursued for its own sake (as it often is); only when standardisation of a step in a care program will lead to an improvement on one or more of the dimensions of quality should it be undertaken.

In many instances, the professional knowledge and motivation of healthcare workers can be most optimally drawn upon by not attempting to standardise it. This is true for those patients that do not fit the care programs, but it is also true for many steps within care programs. The activity of triage, for example, will always contain a large part of clinical judgment, which is most effectively dealt with by a highly experienced healthcare professional. In fact, bureaucratic regulations and inherited ‘standard operating procedures’ often have to be undone to fully profit from the professionals’ skills (flexibilisation). Doing away with complicated schedule systems for outpatient visits (having fixed times for separate types of patients, attempting to spread new patients over the week, etc), for example, and leaving proper scheduling to the scheduler in charge, has proven to be very effective in reducing waiting lists (Murray & Berwick 2003).

Flexible standardisation, then, is about enhancing competencies of professionals. Supported by physician-developed protocols, heart failure nurses are now responsible for therapeutic activities that traditionally would have been seen as restricted to physicians. Standardisation is only about ‘cookbook medicine’ when one confuses the standardisation of the overall care program with the standardisation of the care of an individual patient. Working with care programs is highly skilful work; it implies judging, at every step, whether the next planned step is indeed appropriate for this individual case (Timmermans & Berg 2003). This requires knowledge about the care programs’ purposes, and clinical skills to realise its (in)appropriateness.

Given adequate numbers, even the emergency consultation or admission is predictable at aggregate level, and can thus be planned for. It can be predicted how many patients will visit an outpatient clinic without a scheduled appointment each day, or how many emergency surgeries come to the hospital daily. Separating these patients from the ‘usual’ workflow drastically reduces the interruptions hindering this work, and improves the handling of the emergency cases both in the emergency department and on admission (Litvak & Long 2000).

This should not imply that every individual patient is ‘planned’ in a sequence of individual and dedicated ‘slots’ per unit. Planning every individual patient trajectory ahead in this way would require a substantial planning effort and constant rescheduling activities when plans have to be changed. Unused slots cost time, and matching individual slots to individual patient trajectories, while keeping waiting times at a minimum and optimising resource use, is difficult to achieve. Only for those care trajectories where all individual steps can be predicted 95% of the time may such detailed pre-planning be feasible. Outside of these so called ‘focused factories’, such a ‘solution’ would make matters worse (see Leggat, Chapter 2).

A smarter strategy is to use ‘advanced access’ (Murray & Berwick 2003) principles for all but the most scarce and/or expensive resource. That is to say: services, that is, clinic, ward, and also radiology, lab and operating room, keep their waiting lines very short, so that everybody can be served (almost) immediately when the need arises and no planning of individual slots is necessary. Because demand is predictable, resources can be planned to be available when needed. This is a planning task at the aggregated level of the program: so much MRI capacity is available at day X, so many bloodtests can be done, so many outpatient visits or beds are required. Each individual patient falls in line behind the resource s/he happens to require, and is served in turn. This can be done for diagnostics such as MRI, echo and blood tests, but also for outpatient visits or basic therapeutic interventions.

As said, care programs can properly estimate the amount of resources required at any given time. For advanced access principles to work at all or at most steps along the patient trajectory, however, the variability in patient numbers arriving at any step at the same time also needs to be minimised. Even when ‘demand’ and ‘capacity’ are seemingly optimised at the aggregated level, small variations in the ‘input’ have large consequences for resource use: small peaks leading to rapidly lengthening waiting times, for example, and small dips leading to resource underuse (McManus et al 2003). Care programs also help in this regard. By organisationally separating the distinctive building blocks of a care program (see Box 8.2), the variability of the demands posed on the resources by the incoming patient flow is reduced.

Resource planning is optimised for the individual service capacities ‘handling’ the individual patient’s trajectory, and variations are reduced in the ‘input’ and ‘output’ of the individual process steps. It therefore becomes possible to combine optimal throughput times for the patient with high efficiency for the required service capacities. Planning individual patients for individual slots is only necessary for the most expensive resources, such as operating room time. Of course, we ‘buy’ such overall system efficiency by allowing slight inefficiency at the subsystem level: individual service capabilities will inevitably run at 80–90% occupancy rate, rather than the 100% that could theoretically be achieved by planning every slot. Aiming for 100% optimisation for individual services capabilities would lead to sub-optimisation at the system level: increased throughput times and exponential increase in ‘coordination work’ to push patients through the overcrowded services (Goldratt & Cox 1984). Units that attempt this in practice usually end up realising occupation rates of far below 80% because of all the unfilled slots and time wasted ‘repairing’ the obstructions they themselves cause. Working this way is patient friendly and effective (the likelihood of errors is reduced because of faster and better organised ‘processing’), and the reduction of ad hoc coordination tasks is inevitably a relief for all professionals involved.

Process-supporting information technology and performance monitoring

For professionals to take up responsibility for ‘their’ care program, balanced steering information is a prerequisite. A well-designed system of monitoring of, and feedback on, the outcomes of a particular care process is a core building block of high-quality care (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001). Yet generating such information appears difficult in practice. Record keeping habits are usually well suited to getting the actual work done, but not for secondary purposes such as using this information for quality improvement monitoring, or, even more challenging, for research (Solberg et al 1997). Information capabilities for multiple uses requires more detailed and precise record-keeping habits, which cannot be simply added on to the professionals’ current, and often already overburdened, workloads.

Well-designed care programs solve this problem. The delivery process can be organised so that the secretaries, clerks, nurse practitioners (or patients themselves) enter information in standard formats, so that a more complete record, with comparable and ‘exportable’ data, becomes feasible. Simultaneously, the most expensive care professionals will be less burdened with administrative tasks (Massaro 1993). The care programs form a natural background for this data gathering and analysis. The guidelines underlying the care program form the framework that connects the otherwise isolated data items, giving more insight into the reasons why specific steps were taken or decisions made.

Finally, these guidelines allow the relevant outcomes for monitoring and steering the care program to be deduced. When fed back to the professionals ‘owning’ the care program, a professional-oriented quality system comes into being: measuring, improving and consolidating. By constantly monitoring the impact of the care program on all dimensions of quality, continuous quality improvement can thus become part of everyday work practice. The care programs can be constantly improved and updated when new scientific or practice-derived insights arise.

Information technology is crucial for realising not only this continuous monitoring of performance, but also the whole interplay of working with care programs, re-delegating tasks, optimising flow and resource planning, and measuring performance. Important first steps can be made with all these topics without dedicated IT support, but progress will remain limited. One professional’s information has to be at the other professional’s desk speedily and in a structured way for care programs and task restructuring to function, and information gathered in the care process has to be aggregated to become performance information about the care program. For this, electronic patient record functionalities are required to share information, and order-communication, triage-supporting decision technologies and basic workflow techniques are needed to initiate, support and monitor care programs.

Interestingly, process-supporting information technology is dependent on care programs to succeed. Information technology can only fulfil its potential in a workplace when decision criteria, terminologies and work processes in that workplace are sufficiently standardised. To have a useful electronic patient record, professionals need to use that record in similar ways; to work with order entry, they have to heed the agreements assumed by the application. When such standardisation is not explicitly set as a goal for an information technology implementation project, and when this is not beneficial to the practitioners involved (see also above), the implementation will fail. Working with care programs, therefore, is the optimal way to start to work with information technology in healthcare. The care programs bring the standardisation that information technology requires, and, in its turn, information technology can further improve the cooperation, data management and planning possibilities brought by the care program. 9

9For more on process-supporting information technology in healthcare, see e.g. Coiera 2003& Berg 2004

Pause for reflection

Information technology implementation in the primary care process has a poor track record. Think of examples where information technology failed, and see if you can find examples of ‘unreflexive standardisation’ in these attempts. Think also of successful implementations. Can you discern how standardisation improved the work process in ways deemed relevant by the users?

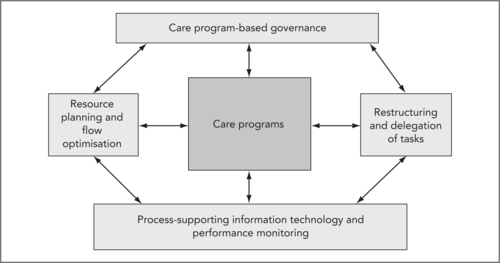

Care program-based governance

Behind this operational restructuring of the healthcare enterprise lies a development that changes the way this enterprise is structured and governed. In addition to being intimately linked to IT development, performance measurement and resource planning, care programs are simultaneously, and perhaps more importantly, the organisational building blocks around which the healthcare organisations of the future will be shaped.

Here, societal developments meet and strengthen the ‘logic’ of enhancing quality and efficiency described above. More and more, payers and patients will demand that the service and technical quality of the care they receive is of the same or higher level as other goods and services they are used to. Long waits, poor service coordination, and high levels of error will no longer be accepted now that the public is learning just how avoidable these problems are. Costs of care delivery will need to be kept in check as the demand for care can potentially outstrip the gross domestic product (GDP) of most countries.

In many countries, one of the ways in which the pursuit of quality and cost control is engineered at the system level is by introducing product-based payment, that is, paying providers a fixed sum for the integrated care of a patient with diagnosis X. The fixed (and ideally severity-adjusted) price should cover all care activities and materials required for the complete care trajectory for patients with this condition. A provider that succeeds in delivering this care at a lower cost per patient can keep the difference; a provider that has higher expenses (maybe because of a higher surgical wound infection rate) loses out on this patient category.

When public performance reporting is linked to product-based payment, a system emerges in which high-quality care is recognised and rewarded, and providers that manage to combine high quality with low cost care thrive. Of course, there is still a gap between the way systems such as diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) are currently being used and introduced throughout the world, and this optimal way of implementing product-based payment. 10 Yet the convergence of ‘pay for performance’ (P4P) schemes with the fundamentals of healthcare financing is clearly under way (Berg et al 2006, Lindenauer et al 2007).

10The care trajectories paid for are often circumscribed by boundaries that are more determined by institutional boundaries (between hospitals and primary care, for example) than by the clinical course of these trajectories and the patient’s experience. In addition, DRG payments seldom pay for the integral costs of care delivery. Often, specialists’ payments or medication costs are separated, and so forth. See for discussions e.g. Porter & Teisberg 2006, Reinhardt 2006.

As we argue above, achieving high-quality and efficient care for a given patient category, and doing so constantly and predictably, is only possible through introducing care programs. By juxtaposing this conclusion with the societal development we describe, we can start to understand why there is such a clear drive to restructure managerial control and governance at this same level. It is at this level, the integrated care around a patient’s diabetes, or liver disease, or hip arthrosis, that the value of the care (the quality bought per dollar/euro spent) is determined – not at the level of the hospital, nor at the level of the individual professional – but at the level of teams of professionals, supporting and managing staff cooperating around specific patient conditions (Porter & Teisberg 2006, Sutton & McLean 2006).

Making these teams responsible for their own clinical and financial results, allowing them to become (more) self-steering can optimise their commitment and motivation to this delivery of value. Rather than drowning in perverse incentives (cost constraints that are unrelated to patient needs, financial rewards irrespective of quality delivered, and so forth) professional motivation is then fully aligned with financial compensation. The teams set and maintain the care programs, and are responsible for measuring, continuously improving and accounting for their (quality and financial) results to patients and payers. They re-delegate tasks among themselves, and are directly responsible for smooth patient flow and the optimally efficient use of resources.

This transition, of course, is not painless. Yet the pain should not run deep. After all, this is ultimately not a loss but a transformation of autonomy: executing autonomy at the level of the individual patient program (resulting in all the problems discussed above) is traded for executing autonomy with the other professionals involved in deciding what an integrated care program should look like. In most current healthcare settings, departments and specialists rule their turf, regardless of how the delineation of that territory links to achieving optimal patient outcomes. Working with integrated care programs implies a radical break from this history. First of all, starting to measure performance and sharing the results with the other professionals and managers involved in the care program is, at least for most professionals, a fundamental break from the past. Whereas high status and financial rewards used to come with just the position of a medical specialist, now one’s actual performance is being measured and discussed by other specialists and managers.

In addition, professionals and departments have to give up part of their individual autonomy in another way. They no longer freely decide how to handle patients, or control input, throughput and output through their clinics, operating room or outpatient offices: the integrated care programs do so. While still in charge of the precise path individual patients will take, the care program does determine the outlines and core steps. Also, the care programs determine the organisation and planning of resources (see Figure 8.2B). This ‘loss’ of autonomy affects everyone: each individual professional in the care program has to be able to work from the assumption that everyone else follows the predetermined path. Also, specialists will get to plan radiology’s timeslots, but through creating the care programs, radiologists will also get a say in defining the indications for which these ‘blocks’ can be used.

There is no blueprint for what this ‘pathway-based model of clinical governance’ (Degeling et al., 2004a and Degeling et al., 2004b) should look like in any particular case. Much is dependent on the particular financial and regulatory context, on the volumes of patients per patient category, on the aims and ambitions of the teams involved and on the vision of the services in which they work. Some facilities and professionals core to a care program may be an integral part of this self-steering group; others may be contracted to provide high-level services (diagnostic, consulting) only when required. In some cases, such new organisational arrangements will be clustered around traditional specialties (cardiological and cardio-surgical care programs or ophthalmological care programs that tend to cluster together in logical wholes). In other cases, organisational arrangements will tie together different medical specialties around a given condition, creating new boundaries within specialties (oncological conditions are a case in point).

Conclusion

A careful and ‘flexible’ standardisation of care programs, we argue, is central to any viable healthcare delivery system of the future. Yet such standardisation is not possible without a thorough restructuring and delegation of tasks, resource planning and flow optimisation, and implementing process-supporting information technology (including performance monitoring). Vice versa, these additional principles can only function properly when integrated with a proper standardisation of care programs. The latter step is crucial, since more often than not, continuous quality improvement (CQI) programs and IT development programs are independently managed, and lack a common focus. Without this, the individual CQI projects remain just that, and the IT implementation is bound to yield disappointing results (Berg 2004).

The vision described here can only be achieved gradually. Healthcare is a complex system (Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America 2001) and changing one part, such as the introduction of a part of a care program, can have unexpected consequences. Redesigning care processes to overcome waiting times can lead to increased waiting times when patients become attracted to this innovative practice, for example. A ‘blueprint approach’ to care innovation, then, can only fail. Rather, care organisations will need to select their own priorities, building upon an analysis of their own resources and advances within the individual elements of the vision described above. Likewise, a care program does not have to be ‘finished’ (if that is at all possible) in one single step. The most urgent quality problems of a certain unit may be solved by standardising only a small part of the care program. Building towards this vision, then, in an iterative, step-by-step way, and learning from all the mistakes made, is the only way to proceed. In this learning process, the vision itself will certainly evolve and, simultaneously, will become part of the organisation’s culture (Ciborra et al 2000).

Acknowledgements

This paper is built upon an earlier publication in the International Journal of Quality in Healthcare (Berg et al 2005).

References

Bell, D.; Mcnaney, N.; Jones, M., Improving healthcare through redesign, BMJ 332 (2006) 1286–1287.

Berenholtz, S.M.; Milanovich, S.; Faircloth, A.; et al., Improving care for the ventilated patient, Jt Comm J Qual Saf 30 (2004) 195–204.

In: (Editor: Berg, M.) Health Information Management: Integrating Information and Communication Technology in Healthcare Work (2004) Routledge, London.

Berg, M.; De Brantes, F.; Schellekens, W., The right incentives for high-quality, affordable care: a new form of regulated competition, Int J Qual Healthcare 18 (2006) 261–263.

Berg, M.; Schellekens, W.; Bergen, C., Bridging the Quality Chasm: Integrating Professional and Organisational Quality, International Journal of Quality in Healthcare17 (2005) 75–82.

Berwick, D.M., Crossing the boundary: changing mental models in the service of improvement, Int J Qual Healthcare 10 (1998) 435–441.

Bouvy, M.L.; Heerdink, E.R.; Urquhart, J.; et al., Effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on diuretic compliance in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled study, J Card Fail 9 (2003) 404–411.

Carroll, J.S.; Rudolph, J.W., Design of high reliability organisations in healthcare, Qual Saf Healthcare 15 (2006) i4–i9.

In: (Editors: Ciborra, C.U.; Braa, K.; Cordella, A.) From control to drift: The dynamics of corporate information infrastructures (2000) Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Coiera, E., Guide to Health Informatics. (2003) Arnold, London.

Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. (2000) National Academy Press, Washington.

Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America, Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. (2001) National Academy Press, Washington.

de Vries, A.; Van Dijk, R.; Hendriks, M.; et al., Medical nurses and the use of expert software in the treatment of patients with congestive heart failure: first year experience, Eur J of Heart Failure Supplement I (2002) 29.

de Vries, G.; Hiddema, U.F., Management van patiëntenstromen. (2001) Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, Houten.

Dy, S.M.; Garg, P.P.; Nyberg, D.; et al., Are critical pathways effective for reducing postoperative length of stay?Medical Care 41 (2003) 637–648.

Goldratt, E.M.; Cox, J., The Goal. A Process of Ongoing Improvement. (1984) Gower, Aldershot.

Grol, R., Between evidence-based practice and total quality management: the implementation of cost-effective care, Int J Qual Healthcare12 (2000) 297–304.

Howell, J.D., Machines and medicine: technology transforms the American Hospital, In: (Editors: Long, D.E.; Golden, J.) The American General Hospital (1989) Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London.

Johnson, Z.K.; Griffiths, P.G.; Birch, M.K., Nurse prescribing in glaucoma, Eye 17 (2003) 47–52.

Klazinga, N., Re-engineering trust: the adoption and adaption of four models for external quality assurance of healthcare services in western European healthcare systems, Int J Qual Healthcare 12 (2000) 183–189.

Leape, L.L.; Kabcenell, A.I.; Gandhi, T.K.; et al., Reducing adverse drug events: lessons from a breakthrough series collaborative, Jt Comm J Qual Improv 26 (2000) 321–331.

Litvak, E.; Long, M.C., Cost and quality under managed care: irreconcilable differences?Am J Manag Care 6 (2000) 305–312.

Luthi, J.C.; Lund, M.J.; Sampietro-Colom, L.; et al., Readmissions and the quality of care in patients hospitalized with heart failure, Int J Qual Healthcare 15 (2003) 413–421.

Massaro, T.A., Introducing Physician Order Entry at a Major Academic Medical Centre: I Impact on Organisational Culture and Behavior, Academic Medicine 68 (1993) 20–25.

McManus, M.L.; Long, M.C.; Cooper, A.; et al., Variability in Surgical Caseload and Access to Intensive Care Services, Anesthesiology 98 (2003) 1491–1496.

Millenson, M.L., Demanding medical excellence. Doctors and accountability in the information age. (1997) University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Mintzberg, H., The Structuring of Organisation. (1979) Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Murray, M.; Berwick, D.M., Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care, Jama 289 (2003) 1035–1040.

Norman, D.A., The psychology of everyday things. (1988) Basic Books, New York.

Parker, C.S., Charting by exception, Caring 16 (1997) 36–40; 42–4.

Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O., Redefining Healthcare. Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. (2006) Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Reinhardt, U.E., The Pricing Of U.S. Hospital Services: Chaos Behind A Veil Of Secrecy, Health Aff 25 (2006) 57–69.

Rozich, J.D.; Howard, R.J.; Justeson, J.M.; et al., Standardisation as a mechanism to improve safety in healthcare, Jt Comm J Qual Saf 30 (2004) 5–14.

Schiele, F.; Meneveau, N.; Seronde, M.F.; et al., Compliance with guidelines and 1-year mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a prospective study, Eur Heart J 26 (2005) 873–880.

Solberg, L.I.; Mosser, G.; Mcdonald, S., The three faces of performance measurement: improvement, accountability, and research, Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 23 (1997) 135–147.

Strauss, A.; Fagerhaugh, S.; Suczek, B.; et al., Social Organisation of Medical Work. (1985) University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Sutton, M.; McLean, G., Determinants of primary medical care quality measured under the new UK contract: cross sectional study, BMJ 332 (2006) 389–390.

Timmermans, S.; Berg, M., The Gold Standard: An Exploration of Evidence-Based Medicine and Standardisation in Healthcare. (2003) Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Wiener, C.L., The Elusive Quest. Accountability in Hospitals. (2000) Aldine de Gruyter, New York.