CHAPTER 3 Instrumentation and Operative Setup for Ankle and Subtalar Arthroscopy

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Diagnostic Assessment

If doubt remains after this assessment, more advanced imaging and possibly diagnostic injections may assist in determining the nature and location of the pathology1. Liberal use of preoperative diagnostic injections can pinpoint symptomatic pathology, which can aid in decision making for the operating room setup. A patient with anterior and posterior ankle pathology may have complete resolution of symptoms with an anterior ankle injection, obviating the need for posterior access and vice versa. For lesions on the talar dome, it is essential to assess the extent of ankle plantar flexion to determine whether an anterior approach alone is sufficient to access the lesion.

Operating Room Setup

Some surgeons may choose to use an arthroscopic pump. Occasionally, fluoroscopy is necessary, which requires a significant amount of space. The arthroscopy tower should be mobile to optimize its position for each case. The components of the arthroscopy tower are listed in Box 3-1 and shown in Figure 3-1. The equipment table is used for therapeutic instruments. The instruments routinely used during the diagnostic arthroscopy (e.g., scalpels, 18-gauge needle, trocars, cannulas, probes) are placed on a Mayo stand for easy accessibility (Fig. 3-2). Backup equipment should be readily available in the event that additional instrumentation is required.

Anesthesia and Positioning

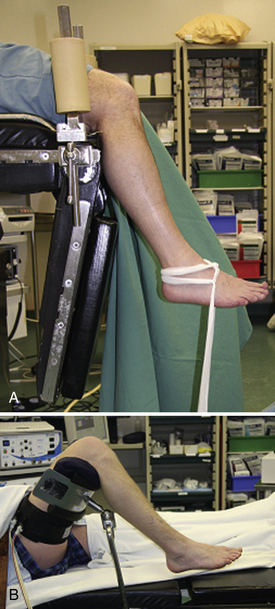

The most appropriate patient positioning for ankle arthroscopy is a matter of the surgeon’s preference. Supine and lateral positions are well described. There are two common variations of the supine position (Fig. 3-3). In the first, the patient is placed supine with the operative leg placed in a knee holder. The knee is placed just distal to the break in the operating room table, and the foot of the bed is lowered to allow the lower leg to rest unsupported.2 A second option is to place the patient supine and use a well-padded thigh holder to position the operative leg such that the hip is flexed 45 degrees and the leg is allowed to hang, providing access to the ankle.3 The lateral position has been described by Parisien (Fig. 3-4).4 It involves placing the patient in a 45-degree lateral position with the operative side up. A platform (box or sheets) is placed underneath the operative leg to elevate it above the nonoperative leg. The hip is externally rotated to access the anterior aspect of the ankle. The leg can be returned to neutral position for access to the lateral or posterior aspects of the ankle. Harbach5 modified the lateral position with the addition of a thigh holder, which allows the ankle to hang similar to the supine position described previously. Although all previously described positions may be used for subtalar arthroscopy, the most common approaches are from the lateral position or posteriorly with the patient in the prone position.

ARTHROSCOPIC METHODS AND INSTRUMENTATION

Distraction

Although several methods of invasive distraction exist, all involve drilling traction pins or wires into bone. The well-described Guhl technique uses two  -inch threaded Steinmann pins and an external distraction device containing a strain gauge and a pivoting distal end.6 The proximal pin is placed into the distal tibia approximately 3 to 5 cm proximal to the ankle joint and 1 cm posterior to the anterior tibial crest. The distal pin is placed into the calcaneus 2 to 2.5 cm anterior to its posterior border and just beneath the peroneal tendons. Both pins are placed in unicortical fashion from lateral to medial aspects. The calcaneus pin should be aimed 20 degrees distally. Many other techniques have been described, including medial distraction with the distal pin in the talus7; medial and lateral distraction8; a single, smooth, 0.045-mm wire passed through the sinus tarsi and attached to weights9; and a single pin through the calcaneus attached to a fracture table.10

-inch threaded Steinmann pins and an external distraction device containing a strain gauge and a pivoting distal end.6 The proximal pin is placed into the distal tibia approximately 3 to 5 cm proximal to the ankle joint and 1 cm posterior to the anterior tibial crest. The distal pin is placed into the calcaneus 2 to 2.5 cm anterior to its posterior border and just beneath the peroneal tendons. Both pins are placed in unicortical fashion from lateral to medial aspects. The calcaneus pin should be aimed 20 degrees distally. Many other techniques have been described, including medial distraction with the distal pin in the talus7; medial and lateral distraction8; a single, smooth, 0.045-mm wire passed through the sinus tarsi and attached to weights9; and a single pin through the calcaneus attached to a fracture table.10

Yates and Grana11 described a means of applying semicontrolled distraction. A small loop is tied in the center of a Kerlix gauze roll. The free ends of the roll are wrapped around the ankle and then passed through the loop. The ends are tied together and then placed underneath the surgeon’s foot. Traction can be added by stepping (similar to stepping on a gas pedal) on the loop underfoot (Fig. 3-5A). Cameron12 modified this technique by passing the loop behind the surgeon’s back, rather than underfoot (see Fig. 3-5B). To apply distraction, the surgeon leans backward.

Takao and colleagues13 use a different bandage configuration to produce equal distraction anteriorly and posteriorly (see Fig. 3-5B). These methods of distraction require little equipment and are very cost effective. However, it is difficult to maintain consistent traction, and some operators may find the multitasking of operating and controlling distraction somewhat onerous. Another disadvantage is that placing the Kerlix roll underfoot or behind the back may compromise the sterility of the procedure.

Through controlled methods, specific amounts of distraction can be applied and maintained with ease. The most common means of controlled distraction is to use one of the many commercially available, sterile foot straps and attach the sling to a tensioning device (Fig. 3-6). This system allows the surgeon to keep both hands free. The foot may be placed into various degrees of plantar flexion by modifying the position of the straps. In many of these systems, the entire apparatus is sterile, which avoids contamination concerns that exist with the semicontrolled techniques. Waseem and coworkers14 routinely use the foot strap technique. However, for tight arthritic ankles, they advocate using a clamp from the AO pinless fixator applied to the patient’s heel and attached to a traction setup. Aydin15 described a distraction technique in which a kyphoplasty balloon is inserted through an arthroscopic portal and is inflated to distract the joint. The entire joint can be visualized, but it is necessary to move the balloon to different positions within the ankle. The controlled techniques are more costly than the uncontrolled and semicontrolled methods.

The acceptable amount of weight and duration of traction depend on the technique used. Guhl6 recommends 7 to 8 mm of distraction with his invasive technique.

Distraction should not be increased after slight bending of the pins has been noticed. The distraction force required usually is 30 to 50 pounds, and it should not continue longer than 45 to 60 minutes to avoid excessive stretching of the ligament. Using cadaveric ankles, Albert and associates16 found that complications were avoided if less than 135 N of distraction force was used. Beyond 135 N, they encountered pin bending and bony destruction of the calcaneus. Takao and colleagues13 compared the bandage distraction technique described by Yates and Grana11 with their own and found better distraction (90% anterior and posterior opening) using the Takao technique with 8 kg of force. They recommended a maximum of 8 to10 kg of force be used because the test subjects felt pain at greater than 10 kg of force. Dowdy and coworkers17 advise that foot straps be used for less than 1 hour at a maximum distractive force of 30 pounds because the subjects in their study developed reversible nerve conduction changes above this threshold.

Invasive distraction is now rarely used. Although it provides greater distraction,17 the risk of complications is also much greater. Box 3-2 lists the potential complications of invasive and noninvasive distraction. Despite the potential for complications with invasive distraction, studies have not shown a significant difference in morbidity for invasive or noninvasive distraction. Ferkel and associates3 found no difference in complication rates between invasive and noninvasive distraction. Guhl6 reported a 10% complication rate in his series using invasive distraction, but ultimately, only three complications were related to distraction and only one (i.e., scarred nodule adjacent to the peroneal sheath) resulted in patient morbidity. Tibial stress fractures through the pin site have been reported.20,21 Stone and Guhl21 recommend avoidance of stressful activities for 6 to 12 weeks postoperatively after the use of invasive distraction.

Box 3-2 Potential Complications of Invasive and Noninvasive Distraction in Ankle Arthroscopy

Data from references 3, 6, 14, 17, 18, and 19.

The contraindications to distraction are found in Box 3-3. Several investigators have found that distraction is rarely necessary.1,22,23 The need for distraction can be minimized or eliminated by using smaller arthroscopic instruments or by a more accurate preoperative diagnosis. Distraction may make some portions of ankle arthroscopy more difficult. The space available deep to the anterior capsule is decreased with traction.1 Because most therapeutic ankle arthroscopy procedures occur within the anterior compartment, many surgeons find distraction unnecessary. Distraction usually is not employed in subtalar arthroscopy.

Box 3-3 Contraindications to Invasive and Noninvasive Distraction in Ankle Arthroscopy

Adapted from Boynton MD, Parisien JS, Guhl JF, Vetter CS. Setup, distraction, and instrumentation. In: Guhl JF, Parisien JS, Boynton MD, eds. Foot and Ankle Arthroscopy. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2004.

Preferred Method: Anesthesia, Position, and Distraction

Ankle arthroscopy with local anesthesia alone has been used only in rare circumstances. We prefer to position the patient supine with the hip flexed 45 degrees and the patient’s thigh supported by a well-padded thigh holder (Fig. 3-7A). The foot is attached to a sterile foot strap, which is fixed to a sterile tensioning device (see Fig. 3-7B). Although the posterolateral portal is accessible, we prefer to use this position for anterior ankle arthroscopy alone. Preoperatively, we determine the need or potential need for posterior ankle arthroscopy. Patients who have posterior ankle pathology are placed in the prone position after an anterior ankle arthroscopy is performed or as a solitary procedure (see Chapter 7). Two separate setups are used for the rare patient who requires anterior and posterior ankle arthroscopies rather than trying to accomplish the anterior and posterior arthroscopies in the supine or lateral position. Noninvasive foot strap distraction is routinely used at 20 to 30 pounds of distraction to facilitate joint visualization. We decrease or remove the traction if increased space is needed for procedures in the anterior compartment beneath the anterior capsule.

Instrumentation

Arthroscopes

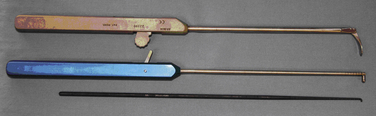

Arthroscopes are available in a variety of lengths, diameters, and lens angles. The most commonly used arthroscopes for ankle arthroscopy are the 4.0-mm, 30-degree arthroscope and the 2.7-mm, 30-degree arthroscope (Fig. 3-8). Occasionally a 70-degree arthroscope may be beneficial to improve visualization of the posterior aspect of the joint. We have found the 4.0-mm, 30-degree arthroscope is effective for most anterior ankle arthroscopies. This arthroscope has the advantage of a greater field of view and increased intra-articular flow compared with the 2.7-mm arthroscope. Subtalar arthroscopy is better and more safely performed with the 2.7-mm arthroscope because of increased joint congruency.

Handheld Instruments

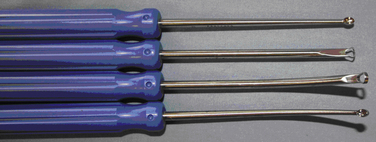

Probes.

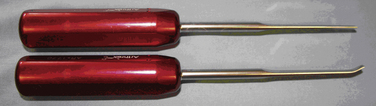

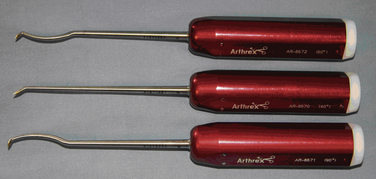

Calibrated probes can increase the accuracy of measurement. Calibrations are preferably marked in ink rather than scored into the metal, because scoring creates stress risers that can lead to instrument breakage.18 Probes come in various curvatures, lengths, and diameters (Fig. 3-9). Articulating probes are commercially available (Arthrex) and allow the probe to enter the joint straight and then articulate and lock at 90 degrees. Shorter probes are more useful in ankle arthroscopy because they have a shorter lever arm and are easier to control.

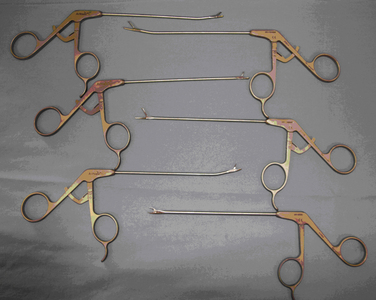

Basket Forceps.

Basket forceps (i.e., punches) are used for débridement. Wide tips are available for greater efficiency, and narrow tips are available for improved control. A variety of angulations exist to facilitate maneuverability (Fig. 3-10).

Curettes.

Curettes are available in ring or cup formation. Ring curettes are often helpful for débriding osteochondritis dissecans lesions. Straight and angled versions are available (Fig. 3-11).

Graspers.

Graspers are used to remove loose bodies or broken instruments from the joint. They are available in straight or curved shafts and in a variety of tip angles (Fig. 3-12).

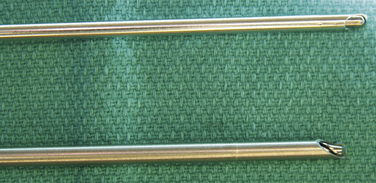

Motorized Instruments

Motorized instruments frequently enable the surgeon to execute the procedure more efficiently. Shavers and burrs of various sizes, angles, and degrees of aggressiveness are available (Fig. 3-15). The larger instruments enable the procedure to be performed quickly; however, the amount of joint space available ultimately determines the size that is used. Less aggressive instruments should be used near vulnerable structures or when learning a new procedure. Conceptually, the instruments are constructed similarly, with a rotating blade or burr housed in a sheath that is attached to suction. The surgeon is able to adjust the direction of rotation and the amount of suction.

1. Van Dijk CN, Scholte D. Arthroscopy of the ankle joint. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:90-96.

2. Andrews JR, Previte WJ, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the ankle. technique and normal anatomy, Foot Ankle. 61985 29-33.

3. Ferkel RD, Dalton DH, Guhl JF. Neurological complications of ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:200-208.

4. Parisien JS, Vangsness T. Operative arthroscopy of the ankle. Three years’ experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;199:46-53.

5. Harbach GP, Stewart JD, Lambert EW, Anderson C. Ankle arthroscopy in the lateral decubitus position. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:597-599.

6. Guhl JF. New concepts (distraction) in ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:160-167.

7. Baker CL, Graham JM. Current concepts in ankle arthroscopy. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1027-1035.

8. Brazytis KE, Hergenroeder PT. Arthroscopic ankle surgery. Overcoming anatomic difficulties with improved techniques. AORN J. 1992;55:492-502.

9. Wright G. Technique tips. Skeletal traction for ankle arthroscopy. Foot Ankle Int. 1996:17-119.

10. Casteleyn PP, Handelberg F. Technical note. Distraction for ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:633-634.

11. Yates CK, Grana WA. A simple distraction technique for ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:103-105.

12. Cameron SE. Technical note. Noninvasive distraction for ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:366-369.

13. Takao M, Ochi M, Shu N, et al. Bandage distraction technique for ankle arthroscopy. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:389-391.

14. Waseem M, Barrie JL. A new distraction method in difficult ankle arthroscopy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2002;41:412-413.

15. Aydin AT, Ozcanli H, Soyuncu Y, Dabak TK. Technical note. A new noninvasive controlled intra-articular ankle distraction technique on a cadaver model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:905.e1-905.e3.

16. Albert J, Reiman P, Njus G, et al. Ligament strain and ankle joint opening during ankle distraction. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:469-473.

17. Dowdy PA, Watson BV, Amendola A, Brown JD. Noninvasive ankle distraction. relationship between force, magnitude of distraction, and nerve conduction abnormalities, Arthroscopy. 121996 64-69.

18. Boynton MD, Parisien JS, Guhl JF, Vetter CS. Setup, distraction, and instrumentation. In Guhl JF, Parisien JS, Boynton MD, editors: Foot and Ankle Arthroscopy, 3rd ed, New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2004.

19. Palladino SJ. Distraction systems for ankle arthroscopy. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1994;11:499-511.

20. Ferkel RD, Guhl JF, Van Beucken K, et al. Complications in ankle arthroscopy. analysis of the first 518 cases, Orthop Trans. 1993 16-726 [abstract]

21. Stone JW, Guhl JF. Pfeffer GB, Frey CC, Anderson RB, Mizel MS, editors. Current Practice in Foot and Ankle Surgery. Pfeffer GB, Frey CC, Anderson RB, Mizel MS, editors. Ankle arthroscopy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Vol 1 1993.

22. Sandmeier RH, Renstrom PAFH. Ankle Arthroscopy. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5:64-70.

23. Sun YQ, Slesarenko YA. Joint distraction may be unnecessary in ankle arthroscopy. Orthopedics. 2006;29:118-120.