Instrumentation

A surgeon’s tools are analogous to those of a carpenter, a mechanic, a research chemist, or an atomic physicist. High-quality instruments are required for the performance of precise and excellent surgery. Although a fine surgeon may overcome the deficits of inferior instruments, the real and potential difficulties presented by using second-rate tools make doing first-rate surgery harder. Good instruments coupled with good surgeons yield the best outcomes.

Throughout this book, reference is made to various instruments utilized in the performance of specific operations. For convenience, this section will codify the panoply of instruments commonly used in gynecologic surgery.

Forceps

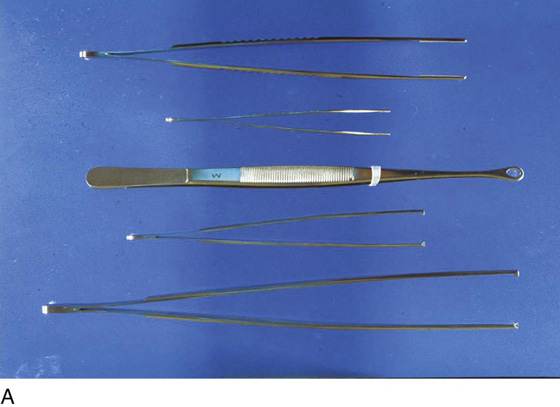

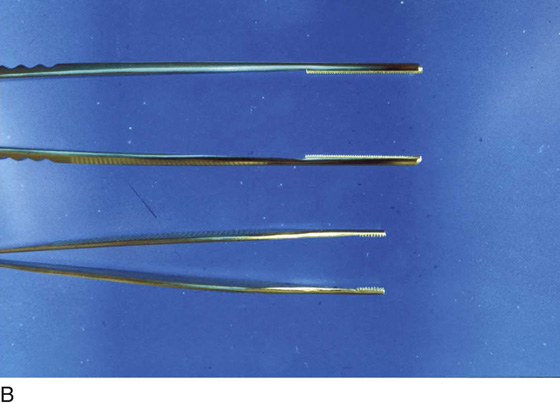

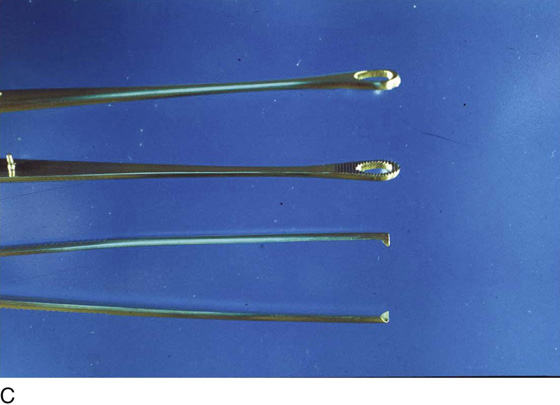

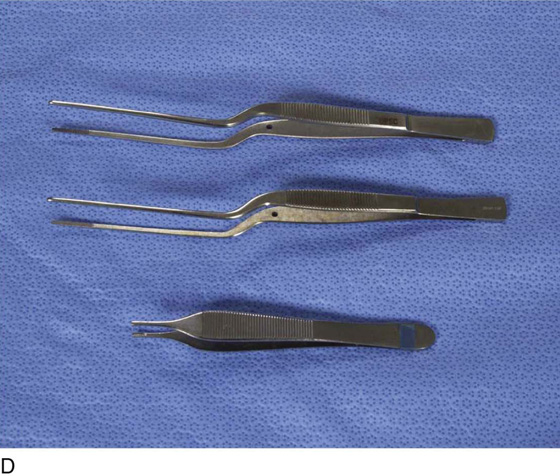

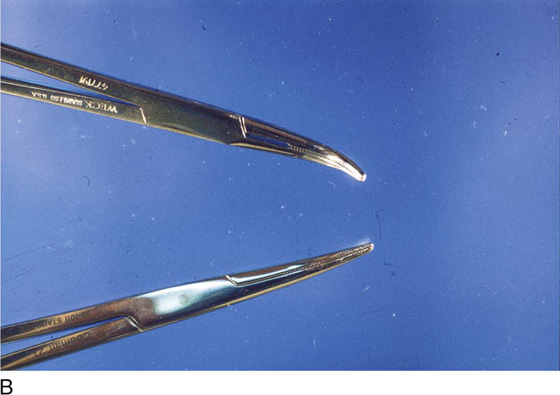

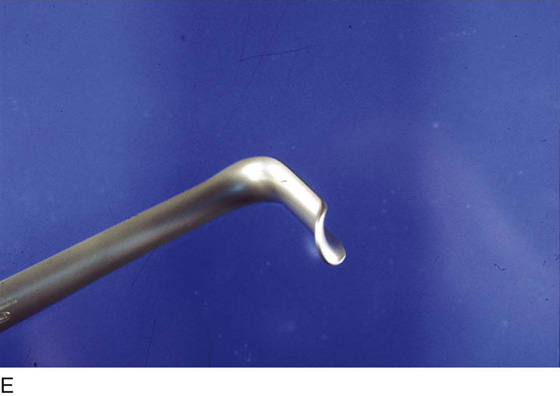

A number of forceps are available. Atraumatic forceps include the Adson and DeBakey instruments. For lymph node and fat dissection, for example, obturator fossa dissection, ring forceps are quite acceptable. Rat-tooth forceps are excellent for traction and for holding tissue securely; however, they may traumatize skin and other delicate tissues. Adson-Brown forceps are the best instruments for grasping skin edges during closure procedures (Fig. 3–1A–C). For fine work deep in the pelvis, for example, dissecting around the ureter or iliac vessels, the author prefers a bayonet forceps equipped with a brown-toothed tip (Fig. 3–1D, E).

Clamps

Clamps may be subdivided into grasping and traction clamps, which include Allis and Ochsner clamps. Grasping clamps are relatively atraumatic, whereas traction clamps are best suited to specimens that will be excised or otherwise removed. Allis clamps are frequently required in vaginal and abdominal surgery. Babcock clamps are atraumatic instruments useful for grasping delicate structures, such as the oviducts, utero-ovarian ligaments, and other fragile tubular structures (Fig. 3–2A, B). Ochsner clamps, for example, may be applied to the cervix for traction during vaginal hysterectomy or on skin scars that are going to be cut out (Fig. 3–2C, D).

Dissecting or hemostatic clamps include standard and long tonsil clamps (Fig. 3–3A, B). These are excellent for fine dissection and for clamping bleeding vessels deep within the pelvis, particularly in strategic locations. The tips of these clamps are tapered and angled. One variety, the right-angle clamp, has a 90° angle (Fig. 3–3C). This is the instrument of choice for isolating large arteries from underlying veins, as occurs during hypogastric artery ligation.

Hemostatic clamps may be straight or curved. Mosquito clamps and the larger Kelly clamps are most commonly used to secure bleeding vessels. Additionally, the fine mosquito clamps may also be used as dissecting tools (Fig. 3–4A, B).

Large vascular pedicle clamps used for hysterectomy or radical hysterectomy should incorporate powerful, atraumatic jaws, a variety of curvatures, and suitable length to facilitate securing these large pedicles. These characteristics are exemplified by the Zeppelin clamps (Fig. 3–5A–C). Haney clamps of the straight and curved variety are the most common pedicle clamps used in the performance of vaginal hysterectomy (Fig. 3–5D).

Scissors

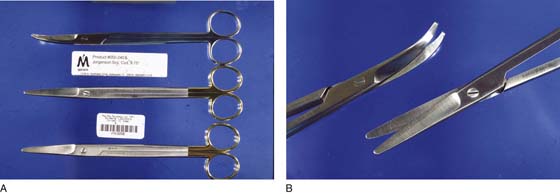

Surgical scissors may be divided into fine dissecting instruments and heavy-duty mass-cutting devices. The first category includes Metzenbaum and Stevens scissors. The former are superior for dissection, whereas the latter are the superlative cutting tools (Fig. 3–6A, B). Large pedicles, vaginal cuffs, and ligaments are best cut with Mayo or Jorgenson scissors (Fig. 3–7A, B).

Knives

Of course, the sharpest mechanical cutting tool is the scalpel. A variety of blade shapes are available for different applications. Scalpel handles may be a standard 6-inch length or an elongated 9- to 10-inch length (Fig. 3–8).

Retractors

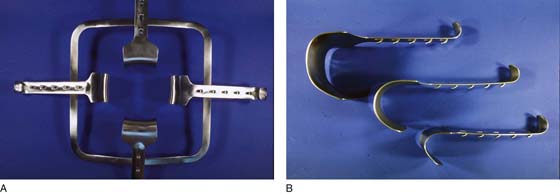

During contemporary abdominal surgery, a self-retaining retractor is essential. Several types are available, ranging from the frame type (Bookwalter and Kirschner) to the spreading type (O’Sullivan-O’Connor). The modern frame retractor has the advantage of remote location, that is, location outside of the abdominal cavity. Its varied blades may be placed within the abdomen and interchanged when necessary without compromising exposure or completely removing the retractor (Fig. 3–9A, B).

The O’Sullivan-O’Connor retractor and the Balfour retractor are the most commonly used devices for pelvic surgery. The O’Sullivan-O’Connor retractor is easy to use and has a sufficient variety of blades to satisfy most clinical conditions. This retractor is equally suitable for transverse and vertical incisions (Fig. 3–10A, B). The Balfour retractor is also a mainstay abdominal retractor in gynecologic and obstetric surgery. This device may be alternatively fitted with standard or deep lateral retractor pieces (Fig. 3–10C, D).

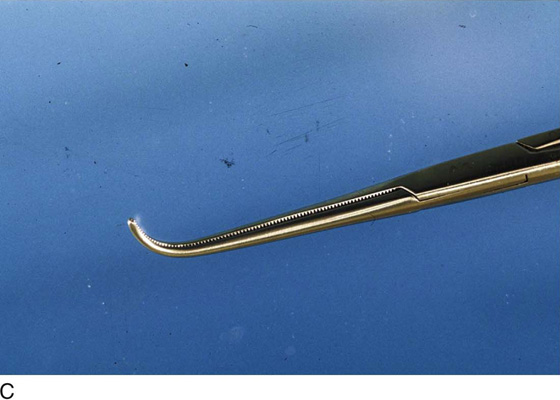

FIGURE 3–1 A. Five surgical forceps are shown. From the top: DeBakey, Adson-Brown, ring, rat-tooth, standard (6-inch), and medium (10-inch) tissue forceps. B. Close-up view of the atraumatic DeBakey (top) and Adson-Brown forceps (bottom). C. Close-up view of the ring forceps, which are ideal for clearing fatty tissue from the obturator fossa and between large vessels. Below is the grasping end of rat-tooth tissue forceps. D. Bayonet forceps (top and center) and Adson forceps (bottom) are ideal for fine tissue handling. E. Another view of the forceps shown in Figure 3–1D.

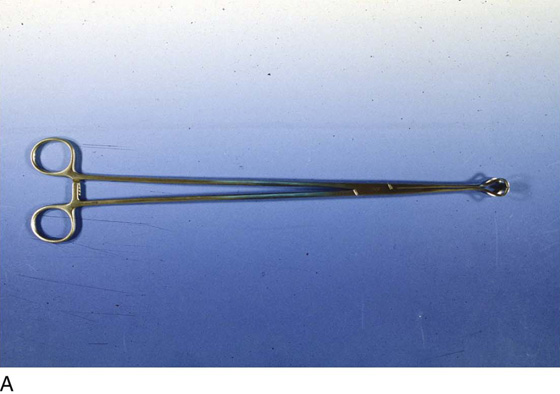

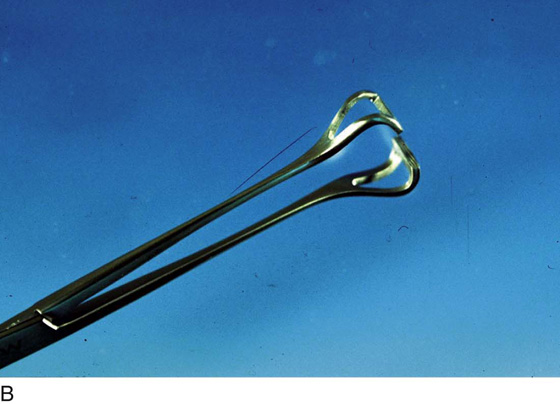

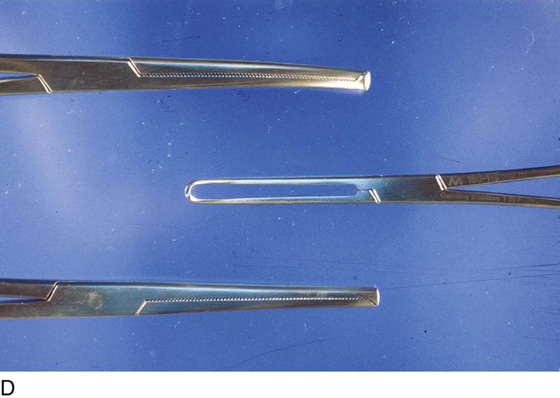

FIGURE 3–2 A. The Babcock clamp, which ranges in length from 8 to 14 inches, is an atraumatic grasping instrument ideal for placing traction on tubular structures while not crushing the tissue. B. Close-up of the shaft and terminus of the Babcock clamp. C. The three clamps illustrated here are curved Ochsner (top), Allis (center), and straight Ochsner clamps (bottom). D. Close-up view of Figure 3–2C. Note the toothed jaws of the Ochsner clamps (top), which grasps very securely but is rather rough on the tissue. In contrast, the Allis clamp (center) grasps tissue firmly but less aggressively than the Ochsner clamp, thereby avoiding crush trauma.

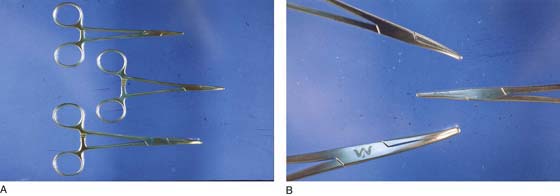

FIGURE 3–3 A. Tonsil dissection and hemostatic clamps are shown in standard and long variations. The two upper clamps are curved, and the lower two are straight. B. The fine, tapered tips of the tonsil clamp are well suited for fine dissection and for securing small bleeding vessels deep within the pelvis. C. The right-angle clamp is used to dissect around and to isolate the hypogastric artery. It is also useful for dissecting the ureter and receiving a traction tape or suture.

FIGURE 3–4 A. The two upper clamps are Halsted mosquito clamps. A curved Kelly clamp is pictured at the bottom. B. The detail in Figure 3–4A shows the heavier aspect of the Kelly hemostatic (bottom) compared with the finer, tapered Halsted mosquito clamp.

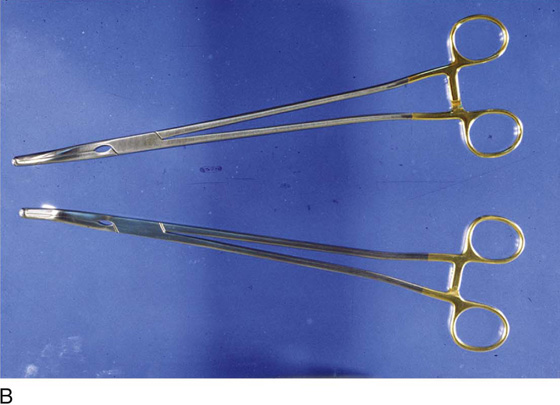

FIGURE 3–5 A. Straight Zeppelin clamp is shown here. Renditions of the same clamps in varying angles of curvature are also available. B. Two extra long Zeppelin clamps (14 inches) used for securing the vaginal angles in deep pelvises. C. Right angulated Zeppelin clamp is ideal for application at the vaginal angle and for clamping across the vaginal cuff. D. Detail of the jaw tip of a Zeppelin hysterectomy clamp. Note the longitudinal groove in one limb of the clamp and the machined ridge in the other limb. E. The grooved-out right jaw and interlocking teeth on the tip of the jaw prevent tissue slippage when the clamp is applied. F. Four Haney clamps are illustrated. These, like the Zeppelin clamps, are available in straight and curved variations. The instruments shown here are curved.

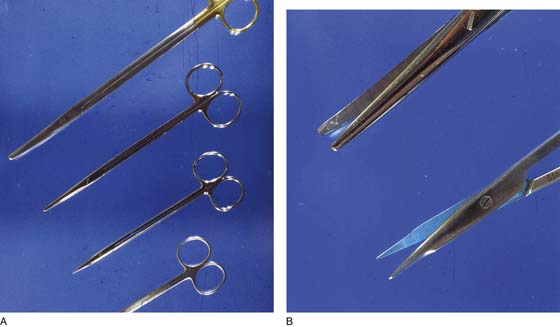

FIGURE 3–6 A. Two general types of dissecting scissors are shown here. The top two are long and standard Metzenbaum scissors. The bottom two are long and short Stevens tenotomy scissors. B. The differences between Metzenbaum and Stevens scissors are apparent. The latter are finer and are beveled for precision cutting.

FIGURE 3–7 A. Mass tissue cutting (e.g., ovarian and parametrial pedicles) requires sharp, heavy-duty scissors as pictured. Mayo and Jorgenson scissors types are most commonly used for hysterectomy and radical hysterectomy. B. Angled Jorgenson scissors (above) are ideal for severing the cardinal ligaments and the vagina during hysterectomy operations.

FIGURE 3–8 Standard and long scalpel handles range from 6 inches to 10 inches in length.

FIGURE 3–9 A. The frame retractor is placed over the open laparotomy incision. A wide selection of blades permits bladder and bowel retraction, as well as sidewall exposure. B. The ratchets on the undersides of the retractor blades are easily interlocked via a series of spaces located on the underside of the frame retractor.

FIGURE 3–10 A. The O’Sullivan-O’Connor retractor is the most commonly used device of its kind for obstetric and gynecologic surgery. B. Several blades are attached to the retractor by wing nuts located fore and aft. C. The Balfour retractor is another self-retaining device. A bladder blade is shown here attached by a wing nut. D. The undersurface of the Balfour retractor is shown in this view. For obese patients, long retractor blades are postoperatively fitted to the frame.

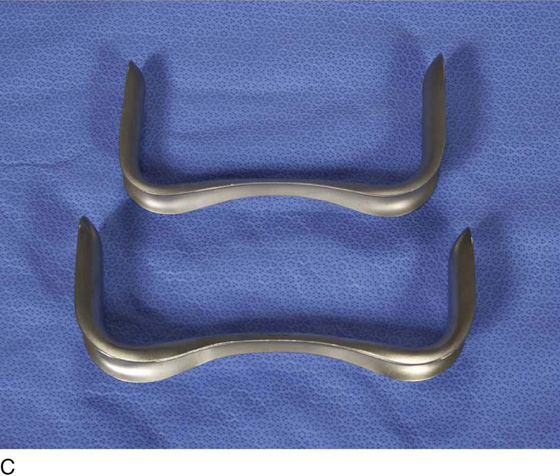

Among the many useful instruments for vaginal surgery are the weighted speculum and the Haney, Sims, Dever, and Breisky-Navratil retractors (Fig. 3–11A–D). The small Richardson retractor is particularly ideal for insertion beneath the anterior cervical circumcision (during vaginal hysterectomy) to facilitate entry into the vesicouterine space (Fig. 3–11E, F). Breisky-Navratil retractors are needed for deep vaginal work (e.g., paravaginal repair) (Fig. 3–11G).

Malleable retractors are well suited to protect the bladder, colon, and other structures during surgery. They are usually available in narrow or wide widths and can be bent to shape for more or less any specific intraoperative need (Fig. 3–11H).

The long-handled vein retractor is the instrument of choice for moving and retracting large vessels (e.g., the external iliac vein) during exposure of the obturator fossa or the hypogastric artery during ureteral dissection (Fig. 3–11I, J).

Needle Holders

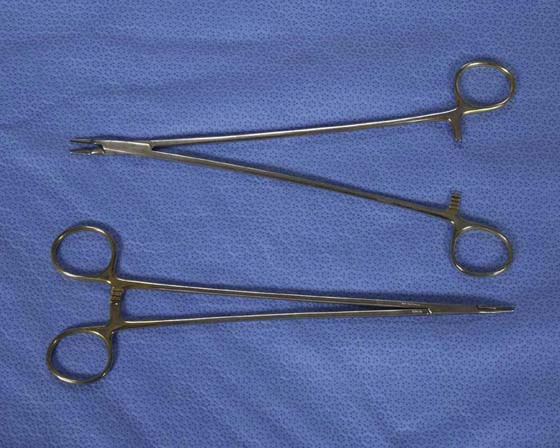

A variety of long and short needle holders are available for gynecologic surgery. Selection depends on the application for the device, the anticipated size of the needle and suture, and the anatomic location.

For fine needles, the long and short Ryder or fine bulldog instruments provide satisfactory options (Figs. 3–12 and 3–13). As an all-purpose needle holder, the long or medium bulldog device is an excellent choice (Figs. 3–14 and 3–15). For vaginal work, or when a curved instrument provides a strategic mechanical advantage, the Haney needle holder is the instrument the author prefers (Fig. 3–16).

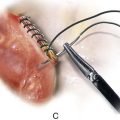

As with any tool, correct usage provides the best overall results. The needle should be driven into the tissue perpendicularly and should traverse through the tissue in its natural arc. The action of needle holder movement is totally within the wrist. When suture ligatures are performed, for example during hysterectomy, the needle must be driven just below the toe of the pedicle clamps. If a transfixing stitch is to be placed, then the same stitch circles the pedicle and is driven toward the heel of the clamp (see Fig. 11–32 in Chapter 11).

Dilators

The operation of dilatation and curettage (D & C) is one of the most often performed surgical procedures in both obstetrics and gynecology.

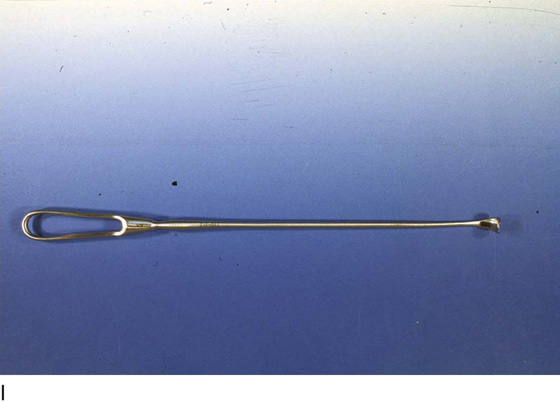

Cervical dilatation is a critical part of the D & C operation, as well as a necessary component of hysteroscopic examination of the uterus. Several types of cervical dilators are available, but the least traumatic are the graduated Hank’s or Pratt devices (Figs. 3–17 and 3–18). For stenotic cervices, the author prefers to initiate dilatation with a baby Hegar dilator (Figs. 3–19 and 3–20).

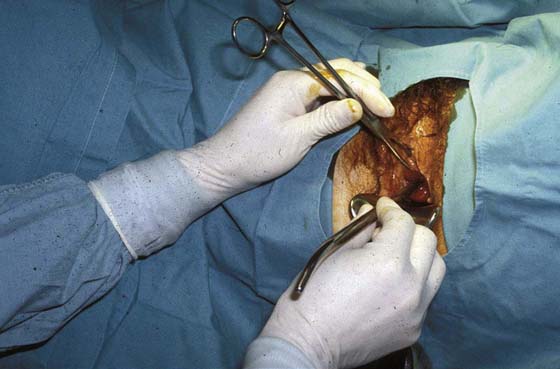

A single-toothed tenaculum should always be used in conjunction with a dilator (Fig. 3–21).

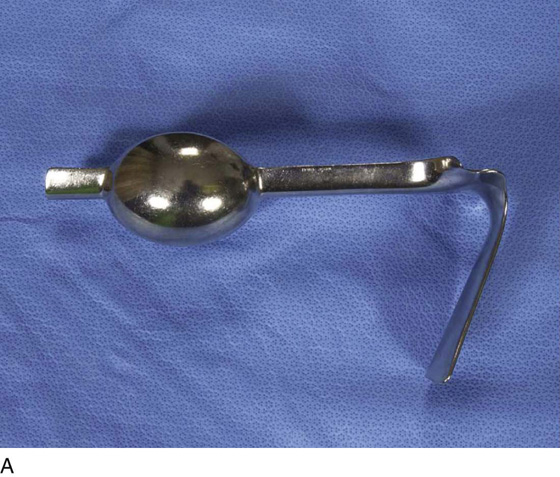

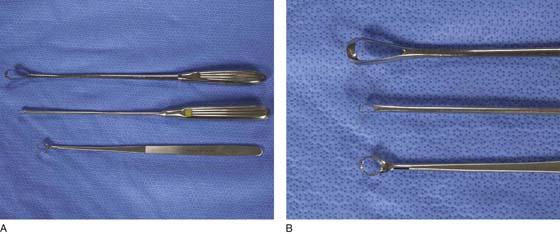

Curettes

The second critical instrument required for the D & C operation is the uterine curette. Several varieties of curettes, including sharp, serrated uterine, and sharp endocervical types, are available. As is the case for uterine dilators, the curette is required to stabilize the cervix with a tenaculum when a curettage is performed (Fig. 3–22A, B).

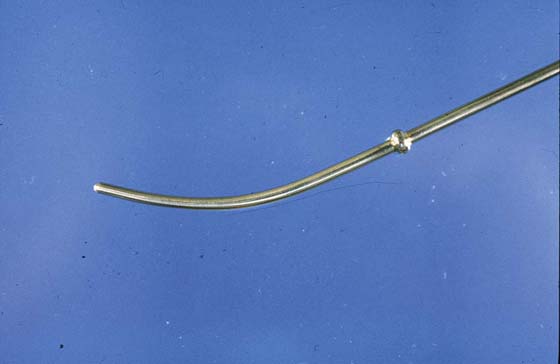

Suction Curettes

Suction curettes are manufactured in a variety of sizes, shapes, and curvatures. Essentially, they are plastic cannulas with an offset terminal opening. They attach to a handpiece fitted with a suction control device. These are used principally for pregnancy termination, evacuation of incomplete or missed abortion, and hydatidiform mole evacuation (Fig. 3–23).

FIGURE 3–11 A. The weighted speculum is utilized as a self-retaining vaginal retractor. It is positioned along the posterior vagina and into the posterior fornix. B. The right-angled Haney retractor is placed into the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs after the peritoneum is opened during vaginal hysterectomy. These retractors provide a barrier between the uterus and the rectum, as well as between the uterus and the bladder. C. Sims retractors may be used to examine the vagina as well as to retract it during surgery. A Sims retractor placed into the vagina along the posterior wall provides the easiest method of exposing the cervix to apply a tenaculum (to the cervix) for hysteroscopic and laparoscopic procedures. D. Dever retractors are utilized during abdominal operations to retract the intestines and occasionally the bladder. Narrow Dever retractors are ideal for lateral vaginal retraction during the performance of vaginal hysterectomy. E. The small, narrow Richardson retractor is an excellent device for retracting the anterior vagina during the initial phase of vaginal hysterectomy. F. The Richardson retractor is also useful for retracting the advanced bladder during the anterior colpotomy portion of vaginal hysterectomy. G. Breisky-Navratil retractors pr vide excellent exposure during vaginal suspension procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension operations. H. Malleable retractors can be bent and molded into many shapes. This allows them to be tailored to a specific clinical situation, whether the approach is abdominal or vaginal. The author favors the broad malleable retractor to place behind the uterus into the cul-de-sac of Douglas to protect the sigmoid colon and rectum. I. The vein retractor is used to retract delicate structures and should be handled gently. This device is the best instrument for retracting the external iliac vein when the obturator fossa is dissected. J. The vein retractor is also useful for retracting the ureter.

FIGURE 3–12 The long Ryder needle holder is an excellent tool for deep suturing when fine needles and 3-0 or small-gauge suture material is required.

FIGURE 3–13 This short, fine bulldog needle holder is used for fine suturing close to or on the surface, for example, in vulvar, lower vaginal, perianal, and urethral surgery.

FIGURE 3–14 The standard bulldog needle holder is a general-purpose needle holder.

FIGURE 3–15 Long bulldog needle holders are useful for suturing deep in the pelvis.

FIGURE 3–16 The curved Haney needle holder offers a great mechanical advantage for driving and retrieving suture needles. The needle is driven with the convex curve of the jaws and is retrieved using the concave curve.

FIGURE 3–17 Hank’s dilator is gently tapered to permit the least traumatic type of cervical dilatation.

FIGURE 3–18 This graduated set of Pratt dilators permits gradual, minimally traumatic cervical dilatation. The dilators are numbered using the French system (division by 3 equals the diameter in millimeters).

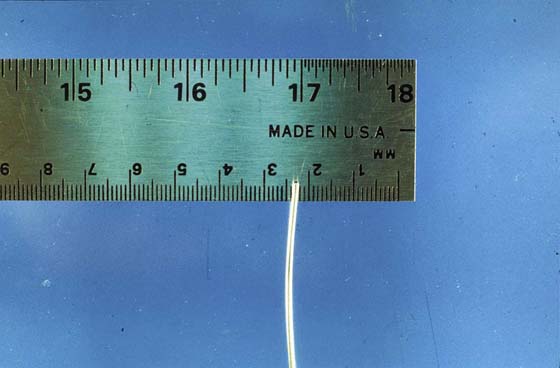

FIGURE 3–19 Above is a Hank’s dilator. Below is a baby Hegar dilator.

FIGURE 3–20 The baby Hegar is 1.5 mm in diameter at one end and 2.5 mm on the opposite end. It is ideal for determining the axis of the cervical canal in cases of cervical stenosis.

FIGURE 3–21 A single-toothed tenaculum should be attached to the anterior lip of the cervix to provide countertraction during cervical dilation.

FIGURE 3–22 A. The bottom curette is a sharp, serrated curette (Haney type), which is ideally suited for curettage, principally in nonpregnant patients. The same can be said for the small, sharp curette (middle). The large, sharp curette at the top is well suited for curetting products of conception. B. Close-up view of the curettes illustrated in Figure 3–22A).

FIGURE 3–23 Suction cannulas are available in a variety of diameters, ranging from 6 to 14 mm. The device illustrated here is 12 mm in diameter.