Chapter 22 Insomnia and sleep disorders

Epidemiology of insomnia

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder across all stages of adulthood, and is often associated with significant medical, psychological and social disturbances.1, 2 It is a prevalent health complaint associated with daytime impairments, reduced quality of life, and increased health care costs. The epidemiological data indicate occasional episodes of insomnia symptoms are reported by one-half of all adults in the US,3, 4 while multiple studies have documented the prevalence of chronic insomnia in 10–15% of the US adult population, and that an additional 25–35% has transient or occasional insomnia identified in various countries.4–7 Reported rates of insomnia in other countries include 21% in Japan,8 19% in France,9 and 18% in Canada.10 Among those people who experience insomnia at least a few nights per week, the most frequent symptoms reported are 1) waking up feeling unrefreshed (34%) and 2) awakening often during the night (32%).3, 4 Less often, adults with insomnia report difficulty falling asleep or awakening early (23–24%).4 Furthermore, up to 25% of children seen in general practice11 and 60% of adults older than 60 years of age experience sleep problems.12, 13

In a telephone survey about sleep and insomnia, in randomly selected French-speaking adults in Quebec, of the total sample 25% were dissatisfied with their sleep, 30% reported insomnia symptoms, and 10% met criteria for an insomnia syndrome.3 Of the respondents, 13% had consulted a health care provider specifically for insomnia in their lifetime, with general practitioners being the most frequently consulted. Daytime fatigue (48%), psychological distress (40%) and physical discomfort (22%) were the main determinants prompting individuals with insomnia to seek treatment. Fifteen percent had used at least 1 herbal/dietary products to facilitate sleep and 11% had used prescribed sleep medications in the year preceding the survey. Other self-help strategies used to facilitate sleep included reading, listening to music and relaxation.3

Symptoms of insomnia

As insomnia is a frequent symptom in the general population, classifications have gradually given more emphasis to its daytime repercussions and to their consequences on social and cognitive functioning.14 The criteria for the diagnosis of insomnia include at least 1 of the following complaints:

(For reviews see Ramakrishnan and Scheid;15 American Academy of Sleep Medicine.16)

Risk factors

General

There are various root causes of insomnia, such as drugs and stimulants that are known to cause insomnia, hormonal problems (e.g. menopause and pregnancy), adjustment sleep disorder (e.g. grief and major stress), environmental changes (e.g. moving house, excessive noise) and limit-setting sleep disorder (e.g. children who need clear boundaries for sleep).4 These need to be addressed and treated in their own right.

Psychological factors

One study exploring sleep patterns in 472 children aged 4–12 years found a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, somatic complaints, attention problems, enuresis, frequent falls, ADHD, pica and fatigue in children suffering insomnia compared with those who do not suffer insomnia.17

School transition

Data from a longitudinal study of 4460 children aged 4–5 years and 6–7 years found sleep problems during school transition are common and are significantly associated with poor health-related quality of life, behaviour, language and learning scores compared with children reported not to have sleep problems.18

Pain

Clearly pain is a common cause of insomnia and is best treated by controlling the pain. Opiates are valuable in pain-associated insomnia.15

Smoking

In a randomly selected sample of 769 individuals (379 men and 390 women, aged 20–98), participants completed 2 weeks of sleep diaries.19 They provided a global report on their sleep, indicated the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and supplied information on health, depressive symptoms, anxiety, caffeine and alcohol use. After controlling for demographic, health, psychological and behavioural variables, light smoking (< 15 cigarettes per day), but not heavier smoking, was associated with self-reported chronic insomnia and reduced sleep (diary recorded as total sleep time and time in bed). Smokers did not differ significantly from non-smokers on diary measures of sleep–onset latency, number of awakenings during the night, wake-time after sleep onset, or sleep efficiency.19

The ARIC study20 is a well-characterised population-based study that specifically correlated sleep complaints in adults to differing covariates. Difficulty falling asleep and difficulty staying asleep was demonstrated to have different causes and outcomes and smoking was a significant correlate. Table 22.1 summarises some of the risk factors for insomnia.

| Life stages |

Pharmacological treatments

The most common treatment for sleep disorders (particularly insomnia) is pharmacological. The efficacy of non-drug interventions has been suggested to be slower than pharmacological methods, but with no risk of drug-related tolerance or dependency. A recent meta-analysis of 24 studies21 of more than 2400 patients found that whilst improvements in sleep with sedative use are statistically significant the magnitude of this effect is small. The analysis demonstrated risk of adverse events as statistically significant particularly in older people at risk of falls and cognitive impairment. In people using any sedatives, the risk of adverse events compared with placebo, was 4.78 times more common for cognitive events, 2.61 times more common for adverse psychomotor events and daytime fatigue was 3.82 times greater than placebo.21 Based on these concerns, the authors concluded that, in people over 60, the benefits of these drugs may not justify the increased risk, particularly if the patient has additional risk factors for cognitive or psychomotor adverse events.

A survey of 100 insomnia cases in hospital found 51% were younger than age 65 and 40% of patients had started experiencing insomnia whilst in hospital.22 Short-acting benzodiazepine medication was used in 88% of the cases and only 11% of patients received information about non-drug alternatives for insomnia. Eighty-two patients felt that the alternatives were healthier, and the majority (n = 67) responded that if an alternative were offered in the hospital, they would be willing to accept it. Female patients were more willing to consider alternatives (P<0.01). First time users of benzodiazepines were more receptive to alternatives compared with chronic users (P<0.002). Preferred alternatives for insomnia included massage therapy, sleep hygiene, music and relaxation techniques (P<0.001). The authors concluded that educational programs are needed for appropriate evidence-based management protocols for insomnia.

Behavioural interventions such as developing healthy sleep patterns, avoiding over-stimulation before sleep, such as watching too much TV14, 20, 23 good sleep hygiene tips, reducing stress levels, and avoiding over-work would appear to be useful first-line advice.

Insomnia and health risks

Cardiovascular

Long-term sleep deprivation may also increase risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) due to sympathetic overdrive and increases in blood pressure according to data from 71 617 women.24 The association between sleep and CHD persisted after adjusting for age, smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors. According to this study, women who were getting 5 or fewer hours of sleep per night had a 39% increased risk of CHD at 10 week follow-up compared to those on 8 hours sleep. Sleep of 6–9 hours was linked to an 18% increase link of CHD.

The integrative approach to the management of insomnia

Lifestyle and behavioural changes

Developing good sleep habits can help. These include:

In a trial of 36 community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their family caregivers, all received written materials describing age- and dementia-related changes in sleep and standard principles of good sleep hygiene.25 The patients and caregivers were then randomised to either an active group (n = 17) receiving specific recommendations about setting up and implementing a sleep hygiene program for the dementia patient or a control group, receiving training in behaviour management skills. Also, the patients in the active group were instructed to walk daily and increase daytime light exposure with the use of a light box. Control participants (n = 19) received general dementia education and caregiver support. Sleep outcomes were derived at baseline, post-test (2 months), and 6-month follow-up. Patients in the active group showed significantly greater (P<.05) post-test reductions in number of night-time awakenings, total time awake at night, and depression, and increases in weekly exercise days than control subjects. At 6-month follow-up, treatment benefit was maintained, with further improvement in reduced night awakenings. The control subjects were noted to spend more time in bed at 6 months than the active group. The authors’ concluded:

Mind–body medicine

Behaviour modification

It has been recently reported that non-drug therapies, such as using sleep diaries and dispelling dysfunctional beliefs about sleep patterns, may be as effective as hypnotics.26 It is important to educate patients about normal sleep patterns for age. For example, the elderly can function on sleep of up to 6 hours per night. Actually counting the number of hours patients sleep can be reassuring. For instance, waking up in the early hours such as 5 a.m. might be considered abnormal for a person, but when counting the total hours of sleep, this might actually be adequate. Also, establishing a proper bedtime routine and avoiding daytime naps might help (see clinical tips at the end of this chapter).

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

A recent Cochrane review identified 6 trials to examine the effectiveness of CBT for sleep problems.27 The final total of participants included in the meta-analysis was 224. The data suggests only a mild effect of CBT for sleep problems in older adults, best demonstrated for sleep maintenance insomnia. The authors’ concluded that, whilst more research is required, ‘when the possible side-effects of standard treatment (hypnotics) are considered, there is an argument to be made for clinical use of cognitive behavioural treatments’.27

Despite these findings, a recent randomised, double-blinded placebo-controlled trial that was not included in the Cochrane review but published in JAMA,28 found CBT was superior to a hypnotic. The study compared CBT with the pharmaceutical zopiclone for the treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults (mean age 61 years). The participants (n = 46) were randomised over 6 weeks to either CBT (sleep hygiene, sleep restriction, stimulus control, cognitive therapy, and relaxation; n = 18), sleep medication (7.5mg zopiclone each night; n = 16), or placebo medication (n = 12). The 2 active treatments were followed up at 6 months. CBT resulted in improved short- and long-term outcomes compared with zopiclone and, overall for most outcomes, zopiclone did not differ from placebo. Participants receiving CBT improved their sleep efficiency from 81.4% at pre-treatment to 90.1% at 6-month follow-up compared with a decrease from 82.3% to 81.9% in the zopiclone group. Participants in the CBT group spent much more time in slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4) compared with those in other groups, and spent less time awake during the night. Total sleep time was similar in all 3 groups; at 6 months, patients receiving CBT had better sleep efficiency using polysomnography than those taking zopiclone. Based on these results CBT is superior to zopiclone treatment both in short- and long-term management of insomnia in older adults.

Another study compared, for 8 weeks, CBT alone with the pharmaceutical agent zolpidem alone, a CBT/zolpidem combination, and a placebo in 63 adults, aged 25–64.29 Therapists taught CBT participants how to identify and curb thoughts that elevate arousal and interfere with sleep. They were advised to reserve the bedroom for sleep and sex, to go to bed only when drowsy, arise at the same time each day, and use other behavioural tactics known to benefit sleep. At 1-year follow-up, the CBT group demonstrated marked improvement with sleep, superior to the zolpidem group, and combination treatment offered no advantage over CBT alone.

Hypnosis

Several studies suggest hypnosis may be useful in managing insomnia, however most of these trials are dated and of poor quality.30 A small study randomised 45 participants and compared hypnotic relaxation technique to stimulus control and placebo as a means of reducing sleep onset latency (SOL).31

The hypnotic group involved 4 weekly sessions of 30-minutes duration and compared stimulus control and placebo from baseline assessment. The subjects in this group were able to sleep more quickly. A similar case study also found hypnotherapy to assist with insomnia.32 Factors that seemed to contribute to long-term response in this small group of patients included a report of sleeping at least half of the time while in bed, increased hypnotic susceptibility and no history of major depression.

A recent study reported on a retrospective chart review performed for 84 children and adolescents with insomnia, excluding those with central or obstructive sleep apnoea.33

All children (mean age 12 years) were offered and accepted instruction in self-hypnosis for treatment of insomnia, and for any other symptoms that was suitable for hypnosis. Seventy-five patients returned for follow-up after the first hypnosis session. If the first session was not useful, patients were offered the opportunity to use hypnosis to gain insight into the cause of their insomnia. The younger children were more likely to report that the insomnia was related to fears. Two or fewer hypnosis sessions were provided to 68% of the patients. Of the 70 patients reporting a delay in sleep onset of more than 30 minutes, 90% reported a reduction in sleep onset time following hypnosis. Of the 21 patients reporting night-time awakenings more than once a week, 52% reported resolution of the awakenings and 38% reported improvement. Of the 41% of children with somatic complaints such chest pain, dyspnoea, functional abdominal pain, habit cough, headaches, and vocal cord dysfunction, 87% reported improvement or resolution of the somatic complaints following hypnosis. The authors concluded the use of ‘hypnosis appears to facilitate efficient therapy for insomnia in school-age children’.33

Meditation and relaxation

Relaxation techniques may be useful when stress and worry cause sleep disruption. An assessment of the literature by an expert panel found a number of well-defined behavioural and relaxation interventions now exist and are effective in the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia.34 The panel found strong evidence for the use of relaxation techniques in reducing chronic pain conditions and behavioural techniques (relaxation and biofeedback) for sleep improvement. However, they concluded ‘it is questionable whether the magnitude of the improvement in sleep onset and total sleep time are clinically significant’.34

A recent pilot study of 14 patients aimed to test mindfulness-based meditation for persistent insomnia.35 Despite methodological limitations, meditation had significant benefit on improving quality of sleep.

Music therapy

Several studies have explored the effect of music on sleep patterns. One study of 28 abused women residing in domestic violence shelters was assessed for anxiety and sleep quality.36 They were randomised to music therapy procedure (music listening paired with progressive muscle relaxation) or to a control. Results from pre- and post-testing indicated that music therapy constituted an effective method for reducing anxiety levels and had a significant effect on sleep quality for the music therapy group, but not for the control group. In another study, 60 Taiwanese elderly men and women aged 60–83, with difficulty sleeping, were randomised to a music group or a control group.37 The music group involved participants listening to their choice of six 45-minute sedative music tapes at bedtime for 3 weeks. Sleep quality was measured before the study and at 3-weekly post-tests. Groups were comparable on demographic variables, anxiety, depressive symptoms, physical activity, bedtime routine, herbal tea use, napping, pain, and pre-test overall sleep quality. Music resulted in significantly better sleep quality, better perceived sleep quality, longer sleep duration, greater sleep efficiency, shorter sleep latency, less sleep disturbance and less daytime dysfunction in the music group compared with the control and pre-testing groups. Sleep improved weekly, indicating a cumulative dose effect.

Physical activity

Exercise

A number of studies with healthy participants have documented the benefits on sleep patterns of exercise during the day. Whilst several reasons are provided, regular physical exercise may promote relaxation and raise core body temperature in ways that are beneficial to initiating and maintaining sleep. A study that surveyed a randomly selected population of adults (mean 54–59 years of age, n = 319 men and 403 women), found that when participating in an exercise program and walking at a normal pace for more than 6 blocks per day, both women and men had significantly reduced risk of developing sleep disorders.38 The findings suggest that a program of regular exercise may be a useful therapeutic modality in the treatment of sleep disorders. A small randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted over 16 weeks reported that participants with sedentary lifestyles and moderate sleep problems experienced significant improvement in sleep from baseline with an exercise program comprised of four 30–40 minutes of endurance training per week when compared with wait-listed controls.39

Exercise for the elderly

Exercise for the elderly may be more difficult, but may also enhance sleep and contribute to an increased quality of life. An early study demonstrated that in older adults with moderate sleep complaints self-rated sleep quality was improved by initiating a regular moderate-intensity exercise program.39

A recent Cochrane review identified 1 trial of 43 participants over 60 years of age with insomnia, to examine the effectiveness of exercise.40 The findings at post-treatment found that total sleep duration, sleep onset latency and scores on a scale of global sleep quality showed significant improvement, but improvements in sleep efficiency were not significant. The Cochrane reviewers conclude:

Yoga

A small 8-week trial of 20 people suffering chronic insomnia found a simple daily yoga treatment was useful in statistically improving sleep-onset, sleep efficiency, total sleep time and sleep quality compared with pre-treatment values.41 Participants practiced the treatment on their own following a single training session with subsequent brief interview and telephone follow-ups. In a recent study with 120 residents from a home for the aged, 69 were stratified based on age (5-year intervals) and randomly allocated to 3 groups, namely the yoga group (physical postures, relaxation techniques, voluntarily regulated breathing and lectures on yoga philosophy), a group for Ayurveda herbal preparation, and a wait-list control (no intervention). The groups were evaluated for self-assessment of sleep over a 1-week period at baseline, and after 3 and 6 months of the respective interventions.42 It was concluded that yoga practice improved different aspects of sleep in a geriatric population as compared to herbal and control groups.

Sunshine and bright light therapy (BLT)

Exercise combined with sunshine may provide additional benefit for sleep disorders. It is generally advisable to increase daytime exposure to the sun and avoid bright lights at night. Darkness and daylight help to control the natural circadian rhythm and the production and release of the pineal hormone melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine). Rest–activity and sleep–wake cycles are controlled by the endogenous circadian rhythm generated by the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the hypothalamus. According to a Cochrane review,43 degenerative changes in the SCN may be a biological basis for circadian disturbances in people with dementia, and might be reversed by stimulation of the SCN by light.

A randomised, prospective trial compared the efficacy of 20-minutes versus 45-minutes bright light exposure (10 000 lux for 60 days) for relieving insomnia in the elderly.44 Compared with baseline, improvement was significantly higher in the 45-minutes versus 20-minutes exposure group at 3 months. At 6 months, variables returned toward baseline in the 20-minutes but not in the 45-minutes group. Another study found 2 evenings of BLT (2500 lux bright light) compared with control (dim red light) improved early morning awakening in insomniacs and day-time functioning up to 1 month after treatment.45

Findings are not so positive for the effectiveness of BLT in managing sleep, behaviour, or mood disturbances associated with dementia, according to a recent Cochrane review that found most studies were of poor quality and revealed inadequate evidence.46 The Cochrane review concluded when:

the possible side-effects of standard treatment (hypnotics) are considered, there is a reasonable argument to be made for clinical use of non-pharmacological treatments. In view of the promising results of bright light therapy in other populations with problems of sleep timing, further research into their effectiveness with older adults would seem justifiable.46

Nutritional influences

Diet

Recently it has been demonstrated that changes in lifestyle behaviours after attending an educational program significantly reduced sleep and stress disorders in as little as 4 weeks, primarily explained by decreasing Body Mass Index (BMI) and/or increasing exercise.47 These are lifestyle modifications that take into significant deliberation nutritional practices.

It is generally advisable to avoid a heavy late meal and over-eating in the evening.

It has been suggested that night eating syndrome may be related to sleep disorders.48 Reducing caffeine intake during the day, particularly close to bedtime, found in colas, some teas (e.g. black and green) and coffee is beneficial and limiting the intake of alcohol.49 Eliminating and or reducing cigarette smoking is also of benefit, as nicotine is a stimulant to the brain.19

Tryptophan and melatonin — food sources

Tryptophan has a long research history for sleep disorders, spanning some 3 decades. There are foods and plants rich in tryptophan and melatonin that are considered as being helpful in inducing sleep. Studies have identified indolamines such as serotonin, tryptamine, and melatonin in some edible and medicinal plants that can assist with sleep.50 For example, the pulp of under-ripe and ripe yellow banana contains 5-hydroxytryptamine at concentrations of 31.4 and 18.5ng/g respectively.51 Corn, rice, barley grains, and ginger showed the highest concentrations of melatonin, at 187.8, 149.8, 87.3, 142.3ng/100g, respectively. Pomegranate and strawberry also showed a low level of indolamines (8–12μg/g serotonin, 4–9μg/g tryptamine, and 13–29ng/100g melatonin).

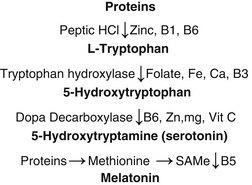

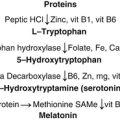

The amino acid tryptophan is necessary for the pineal gland to make both serotonin and melatonin. In animal models, consumption of L-tryptophan can cause a rise in blood melatonin levels by fourfold. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) is also necessary for the production of serotonin from tryptophan (see Figure 22.1). Protein food sources of tryptophan can be comparable to pharmaceutical grade tryptophan for the treatment of insomnia.

Tryptophan

A double-blind placebo-controlled study of 57 insomniacs were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 conditions:52 protein source tryptophan (de-oiled gourd seed; an extremely rich source of tryptophan, 22mg tryptophan/1g protein) in combination with carbohydrate; pharmaceutical grade tryptophan in combination with carbohydrate; or carbohydrate alone. Only 49 patients completed the 3-week protocol. Both protein source tryptophan with carbohydrate and pharmaceutical grade tryptophan, but not carbohydrate alone, resulted in significant improvement on subjective and objective measures of insomnia. Protein source tryptophan with carbohydrate alone proved effective in significantly reducing time awake during the night.52

Melatonin supplement

A recent Cochrane review identified 9 placebo-controlled trials to assess the efficacy of melatonin supplement for jet lag.53

Eight trials found if melatonin was taken close to the target bedtime at the destination (10 p.m. to midnight), this resulted in decreased jetlag from flights crossing 5 or more time zones.53 Whilst daily doses of between 0.5 and 5mg are similarly effective, people fall asleep faster and sleep better with dosages greater than 5mg than 0.5mg. Slow-release melatonin (2mg) was relatively ineffective, suggesting that a short-lived higher peak concentration of melatonin works better. Benefit is greater the more time zones are crossed and less for westward flights. Adverse events are low but case reports suggest epileptics and patients with depression taking warfarin should avoid its use. The authors’ concluded ‘melatonin is remarkably effective in preventing or reducing jet lag, and occasional short-term use appears to be safe’.53

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 62 children with idiopathic chronic sleep-onset insomnia were randomised to either 5mg melatonin or placebo at 7 p.m.54 The study consisted of a 1-week baseline period, followed by a 4-week treatment. Total sleep improved significantly with melatonin treatment compared to placebo. Melatonin treatment also significantly advanced sleep onset by 57 minutes, sleep offset by 9 minutes, and melatonin onset by 82 minutes, and decreased sleep latency by 17 minutes. Lights-off time and total sleep time did not change. The authors’ concluded melatonin ‘improves health status and advances the sleep-wake rhythm in children with idiopathic chronic sleep-onset insomnia’.54

A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of 22 elderly people (over 65) with a history of sleep disorder complaints were randomised to 2 months of melatonin (5mg/day) or placebo.55 Melatonin significantly improved sleep quality, behavioural disorders and mood levels (depression and anxiety) compared with placebo. Melatonin administration also facilitated discontinuation of therapy with conventional hypnotic drug. Another trial of a night-time milk containing ultra-low dosage (10–40 nanogram/litre) melatonin drink may benefit institutionalised elderly by increasing their daytime activity.56

A very small trial of 7 children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) were randomised to melatonin or placebo. For those who completed the trial, sleep improved significantly with melatonin supplementation resulting in reduced waking per night, earlier onset of sleep and increased duration of sleep.57

Recent research found 3mg of melatonin at bedtime was effective for the treatment of sleep problems in children with ASD and fragile X syndrome.58

Melatonin also plays a role in facilitating withdrawal of addictive medication such as benzodiazepines, which can cause significant adverse events such as drowsiness and falls in the elderly, whilst improving sleep quality.59, 60

A double-blind placebo-controlled study of 45 elderly patients taking low-dose anxiolytic benzodiazepines, randomised to melatonin 3mg or placebo for 6 weeks, found no benefit of melatonin compared with placebo.61

A systematic review of the literature found an overall trend towards efficacy of melatonin on sleep quality in the elderly, including those with Alzheimer’s dementia.62

Nutritional supplements

Magnesium

Periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS), with or without symptoms of restless leg syndrome (RLS), may cause sleep disturbances. A small, open, clinical and polysomnographic study researched 10 patients (mean age 57 years; 6 men, 4 women) suffering from insomnia related to PLMS (n = 4) or mild-to-moderate RLS (n = 6).63 Following oral magnesium treatment (dose of 12.4mmol in the evening) over a period of 4 to 6 weeks, PLMS associated with arousal significantly decreased, PLMS without arousal were also moderately reduced and sleep efficiency improved. In 7 of the patients, estimating their sleep and/or symptoms of RLS as improved after therapy, the effects of magnesium on PLMS and PLMS-A were even more pronounced. The study indicates that magnesium treatment may be a useful therapy in patients with mild or moderate RLS or PLMS-related insomnia.63

Herbal medicine

An excellent review article assesses the efficacy and safety of stimulants and sedatives in sleep disorders.64 The authors postulated that herbal sedatives may have evidence of efficacy based on observation studies that certain plant flavonoid compounds bind to benzodiazepine receptors. Caution is required with their use combined with other sedatives as they may have an overall additive effect. Withdrawal symptoms such as delirium have also been reported with chronic valerian use.65 Whilst these herbs have a mild sedative effect, the effect can be strong in sensitive people.

Kava also displays anti-anxiolytic effects.66 The ethanolic form and use in high doses has been associated with hepatotoxicity.67, 68 Consequently this preparation is banned in Australia with limitations in dosage.69 (See Chapter 4 for more detail.)

Valerian (Valerian officinalis)

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of an extensive literature search identified 16 eligible studies examining a total of 1093 patients.70 The available evidence suggests that valerian may improve sleep quality without producing serious side-effects, although most studies have significant methodologic problems, with considerable variations in the valerian doses and preparations used, and with the length of treatment. Another systematic review of RCTs also suggests that valerian might improve sleep quality without producing significant side-effects,71 although 1 systematic review whilst supporting that valerian as being a safe herb associated with rare adverse events, did not support the clinical efficacy of valerian as a sleep aid for insomnia.72

One randomised, double-blind trial found valerian was shown to have positive benefit on sleep although trial quality was generally low.73 Two studies found valerian to be equally effective to oxazepam and triazolam in randomised, double-blind, clinical comparative studies.74, 75 When compared with triazolam in the small, randomised control trial of 9 healthy individuals, valerian had less adverse effects on cognitive function.75 In another study the effect of an aqueous extract of valerian root was assessed on subjectively rated sleep measures studied on 128 people.76 Each person received 9 samples to test (3 containing placebo, 3 containing 400mg valerian extract and 3 containing a proprietary over-the-counter valerian preparation) presented in random order, and were taken on non-consecutive nights.

Valerian produced a significant decrease in subjectively evaluated sleep latency scores and a significant improvement in sleep quality especially among people who considered themselves poor or irregular sleepers, smokers, and people who thought they normally had long sleep latencies.76

Another double-blind study of valerian compared with placebo also showed benefit for insomnia, however more robust quality studies are required.77

Valerian and kava (Kava Kava) combined

A combined formula consisting of valerian and kava herbs were compared in a pilot study of 24 patients suffering from stress-induced insomnia.78 Patients were treated for 6 weeks with kava 120mg daily, followed by 2 weeks off treatment and then (5 having dropped out) 19 received valerian 600mg daily for another 6 weeks. Overall stress severity and insomnia were significantly relieved by both compounds (P < 0.01) equally. Side-effect profile was similar for both; 58% with each herb respectively and the commonest effect was vivid dreams with valerian (16%), followed by dizziness with kava (12%).78

Valerian and hops (Humulus lupulus) extract

The herb hops is well known as a bitter agent in the brewing industry and has a long traditional history in medicine to treat sleep disturbances.79

A pilot study of 30 patients with insomnia resulted in better quality sleep with the fixed valerian–hop extract combination (Ze 91019 extract) after 2 weeks of treatment, with no adverse events noted.80 The exact mechanism for its pharmacological activity is not clear, but it is postulated from in vitro studies that partial agonistic activity on adenosine receptors (A1Ars) for the fixed extract and valerian extract may be contributing to its sleep-inducing effect.81

A randomised placebo-controlled trial (n = 184) of a valerian–hops combination versus diphenhydramine showed a modest hypnotic effect relative to placebo for adults suffering mild insomnia.82

Also, sleep improvements with a valerian–hops combination were associated with improved quality of life, did not produce rebound insomnia upon discontinuation of use, and both treatments appeared safe.82

Another randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind sleep-EEG study in a parallel design using electrohypnograms of 42 subjects found time spent in sleep was significantly higher for subjects who took a single dose of valerian–hops fluid extract compared with placebo.83

Physical therapies

Massage therapy

A study aimed to examine the effects of massage therapy versus relaxation therapy on sleep, substance P, and pain in fibromyalgia patients.87 Twenty-four adult fibromyalgia patients were randomised to a massage therapy or relaxation therapy group. They received 30-minute massage treatments twice weekly for 5 weeks. Of interest, both groups displayed a decrease in anxiety and depressed mood immediately after the first and last therapy sessions, however, only the massage therapy group reported an increase in the number of sleep hours and a decrease in their sleep movements. In addition, substance P levels decreased, and the patients’ physicians assigned lower disease and pain ratings and rated fewer tender points in the massage therapy group.

A recent Cochrane review88 identified studies in which babies under the age of 6 months were randomised to an infant massage or a no-treatment control group. Twenty-three studies were included in the review. Fourteen studies were excluded, 13 of which were regarded at high risk of bias. The results of 9 studies suggest that infant massage has no effect on growth, but provided some evidence suggestive of improved mother–infant interaction, sleep and relaxation, reduced crying and a beneficial impact on a number of hormones controlling stress. The authors’ concluded:

Acupuncture

A recent Cochrane review conducted to investigate the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating insomnia that included 7 eligible studies for review, involving 590 participants, found most studies were of low methodological quality and were diverse in the types of participant, acupuncture treatments and sleep-outcome measures used.89 This severely limited the ability to pool the findings and draw conclusions. Therefore the review concluded that currently there is a lack of high quality clinical evidence supporting the treatment of people with insomnia using acupuncture.

A recent study of 40 patients suffering insomnia aimed to evaluate the efficacy of an acupressure device, ‘H7-insomnia control’, positioned on Heart-7 (HT-7) points of both wrists during the night, and assessed general health, anxiety levels, sleep quality and the urinary melatonin metabolite 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate determination.90

Compared with the placebo group, the H7-treated patients demonstrated improved quality of sleep, reduced anxiety levels in insomniacs to a higher extent. Furthermore, the 24 hours urinary melatonin metabolite rhythm obtained at the end of treatment was found to be of normal levels in a higher percentage of H7-treated patients compared with placebo group.90

A similar trial assessing HT-7 point acupressure in cancer patients with insomnia was also beneficial in improving quality of sleep.91

Aromatherapy

A number of essential oils from fragrant plants, such as lavender, have been reported to help promote relaxation and sleep in a pilot study.92 A recent Cochrane review identified 3 small trials for aromatherapy, but only 1 trial had useable data. This trial showed a statistically significant treatment effect in favour of aromatherapy intervention on measures of agitation and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia and thus may play a role in inducing sleep.93

Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea (OSAH)

Sleep apnoea can be a serious sleep disorder. People who exhibit sleep apnoea stop breathing for 10 to 30 seconds at a time while they are sleeping.94 These short stops in breathing can happen up to 400 times every night, disrupting sleep patterns, hence we have briefly included it in our compilation of disordered sleep patterns.

A Cochrane review95 aimed to determine whether weight loss, sleep hygiene and exercise were effective in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoeas. No completed RCTs were identified for this analysis and the authors’ concluded a need for RCTs of these commonly used treatments in obstructive sleep apnoeas.95

Jaw splint — sleep apnoea

A recent Cochrane review included 16 studies (745 participants) that assessed oral appliances (OA) with a control and in several trials compared with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).96

Overall, the authors’ concluded there is:

increasing evidence suggesting that OA improves subjective sleepiness and sleep disordered breathing compared with a control. CPAP appears to be more effective in improving sleep disordered breathing than OA. The difference in symptomatic response between these 2 treatments is not significant, although it is not possible to exclude an effect in favour of either therapy. 96

Until there is more definitive evidence available, the reviewers recommend:

with regard to symptoms and long-term complications, it would appear to be appropriate to recommend OA therapy to patients with mild symptomatic OSAH, and those patients who are unwilling or unable to tolerate CPAP therapy.96

Long-term data on more severe symptoms of sleep disorder, quality of life and cardiovascular health are required.

Summary

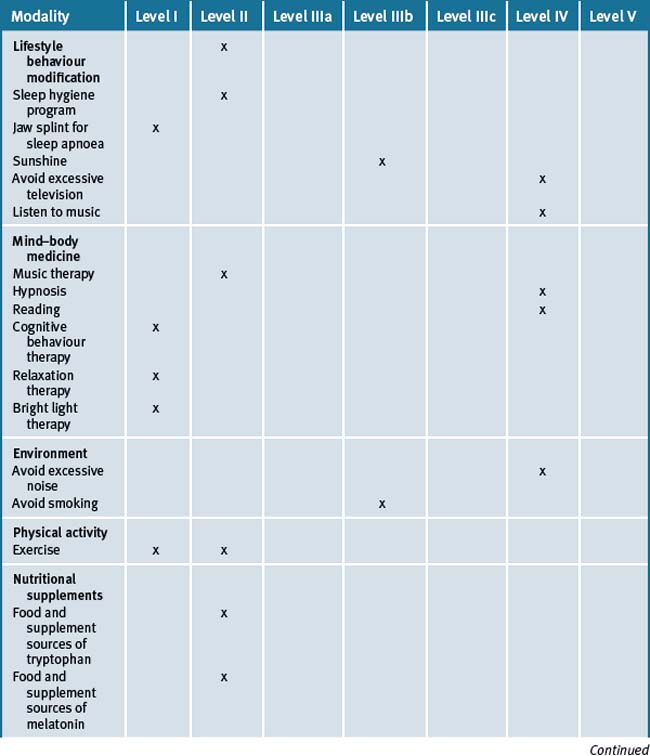

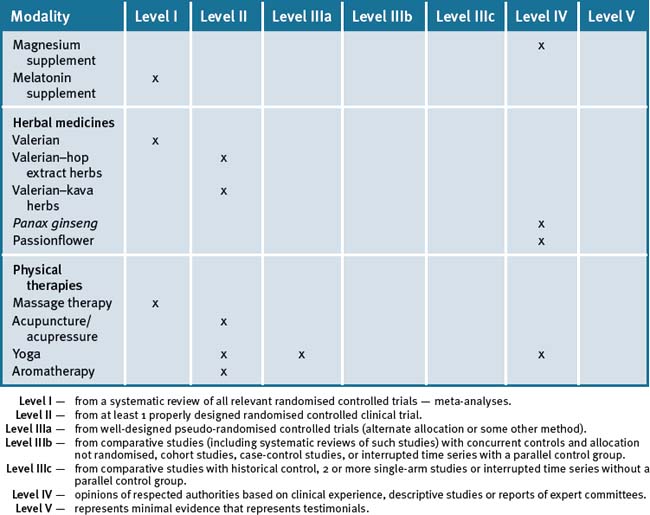

There is a strong scientific rationale for the use of an integrative approach to assist with the management of insomnia. The integrative approach may include a combination of modalities that also promote and sustain a healthy lifestyle, particularly correcting diet, reducing caffeine, restoring sleep, sun exposure, reducing stress levels and exercise which are essential in the management of insomnia. Table 22.2 summarises the evidence for complementary medicine/therapies.97

Clinical tips handout for patients — insomnia

1 Lifestyle advice

General advice about sleep

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Melatonin

Vitamin D (cholecalciferol 1000 international units)

Doctors should check blood levels and suggest supplementation if levels are low.

Magnesium and calcium (best taken together)

Multivitamins, especially B-group

Herbs

Valerian

Valerian and kava combined

1 NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults. NIH Consens Sci Statements. 2005 Jun 13-15;22(2):1-30.

2 Becker P.M. Insomnia: prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(4):855-870.

3 Morin C.M., Le Blanc M., Daley M., et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviours. Sleep Med. 2006;7(2):123-130.

4 Zammit G.K. The prevalence, morbidities, and treatments of insomnia. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6(1):3-16. Review

5 Drake C.L., Roehrs T., Roth T. Insomnia causes, consequences, and therapeutics: an overview. Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(4):163-176. Review

6 Ancoli-Israel S., Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. I. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S347-S353.

7 Ford D.E., Kamerow D.B. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479-1484.

8 Kim K., Uchiyama M., Okawa M., et al. An epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population. Sleep. 2000;23:41-47.

9 Leger D., Guilleminault C., Dreyfus J.P., et al. Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. Sleep Res. 2000;9:34-42.

10 Ohayon M.M., Caulet M., Guilleminault C. How a general population perceives its sleep and how this relates to the complaint of insomnia. Sleep. 1997;20(9):715-723.

11 Blunden S., Lushington K., Lorenzen B., et al. Are sleep problems under-recognised in general practice? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(8):708-712.

12 Neckelmann D., Mykletun A., Dahl A.A. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30(7):873-880.

13 Almeida O.P., Pfaff J.J. Sleep complaints among older general practice patients: association with depression British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55:864-866.

14 Thompson M.D., Christakis D.A. The Association Between Television Viewing and Irregular Sleep Schedules Among Children Less Than 3 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:851-856.

15 Ramakrishnan K., Scheid D.C. Treatment options for insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(4):517-526. Review

16 American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2nd ed. Westchester, Ill: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

17 Leger D., Poursain B. An international survey of insomnia: under-recognition and under-treatment of a polysymptomatic condition. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(11):1785-1792.

18 Quach J., Hiscock H., Canterford L., et al. Outcomes of Child Sleep Problems Over the School-Transition Period: Australian Population Longitudinal Study. PEDIATRICS. 2009 May;123(5):1287-1292. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1860

19 Riedel B.W., Durrence H.H., Lichstein K.L., et al. The relation between smoking and sleep: the influence of smoking level, health, and psychological variables. Behav Sleep Med. 2004;2(1):63-78.

20 Phillips B., Mannino D. Correlates of sleep complaints in adults: the ARIC study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1(3):277-283.

21 Glass J., Lanctôt K.L., Herrmann N., et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:1169.

22 Azad N., Byszewski A., Sarazin F.F., et al. Hospitalised patients’ preference in the treatment of insomnia: pharmacological versus non-pharmacological. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003 Summer;10(2):89-92.

23 Johnson J.G., Cohen P., Kasen S., et al. Association between television viewing and sleep problems during adolescence and early adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(6):562-568.

24 Ayas N.T., White D.P., Manson J.E., et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:205-209.

25 McCurry S.M., Gibbons L.E., Logsdon R.G., et al. Nighttime insomnia treatment and education for Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):793-802.

26 Becker P.M. Sleep diaries and dispelling dysfunctional beliefs may be as effective as hypnotics. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7:13-20.

27 Montgomery P., Dennis J. Cognitive behavioural interventions for sleep problems in adults aged 60+. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (1):2003. CD003161

28 Sivertsen B., Omvik S., Pallesen S., et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851-2858.

29 Lamberg L. CBT outperforms hypnotics in sleep-disorder patients. Psychiatr News. 2005;40:30.

30 Anderson J.A., Dalton E.R., Basker M.A. Insomnia and hypnotherapy. J Roy Soc Med. 1979;72:734-739.

31 Stanton H.E. Hypnotic relaxation and the reduction of sleep onset insomnia. Int J Psychosom. 1989;36(1-4):64-68.

32 Becker P.M. Chronic insomnia: outcome of hypnotherapeutic intervention in six cases. Am J Clin Hypn. 1993;36(2):98-105.

33 Anbar R.D., Slothower M.P. Hypnosis for treatment of insomnia in school-age children: a retrospective chart review. BMC Pediatrics. 2006;6:23.

34 NIH Technology Assessment Panel on Integration of Behavioural and Relaxation Approaches into the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Insomnia. Integration of behavioural and relaxation approaches into the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia. JAMA. 1996;276(4):313-318.

35 Heidenreich T., Tuin I., Pflug B., et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for persistent insomnia: a pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(3):188-189.

36 Hernandez-Ruiz E. Effect of music therapy on the anxiety levels and sleep patterns of abused women in shelters. J Music Ther. 2005;42(2):140-158.

37 Lai H.L., Good M. Music improves sleep quality in older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(3):234-244.

38 Sherrill D.L., Kotchou K., Quan S.F. Association of Physical Activity and Human Sleep Disorders. Archive of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1894-1898.

39 King A.C., Oman R.F., Brassington G.S., et al. Moderate-intensity exercise and self-rated quality of sleep in older adults. A randomised controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;277:32-37.

40 Montgomery P., Dennis J. Physical exercise for sleep problems in adults aged 60+. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2002. CD003404

41 Khalsa S.B. Treatment of chronic insomnia with yoga: a preliminary study with sleep-wake diaries. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004;29(4):269-278.

42 Manjunath N.K., Telles S. Influence of Yoga and Ayurveda on self-rated sleep in a geriatric population. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121(5):683-690.

43 Forbes D., Morgan D.G., Bangma J., et al. Light Therapy for Managing Sleep, Behaviour, and Mood Disturbances in Dementia. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (2):2004. CD003946

44 Kirisoglu C., Guilleminault C. Twenty minutes versus forty-five minutes morning bright light treatment on sleep onset insomnia in elderly subjects. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):537-542.

45 Lack L., Wright H., Kemp K., et al. The treatment of early-morning awakening insomnia with 2 evenings of bright light. Sleep. 2005;28(5):616-623.

46 Montgomery P., Dennis J. Bright light therapy for sleep problems in adults aged 60+. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (2):2002. CD003403

47 Merrill R.M., Aldana S.G., Greenlaw R.L., et al. The effects of an intensive lifestyle modification program on sleep and stress disorders. J Nutr Health Ageing. 2007;11:242-248.

48 Winkelman J.W. Sleep-related eating disorder and night eating syndrome: sleep disorders, eating disorders, or both? Sleep. 2006;29(7):876-877.

49 Philip P., Taillard J., Moore N., et al. The effects of coffee and napping on nighttime highway driving: a randomised trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(11):785-791.

50 Reiter R.J., Reiter R.J., Tan D.X., et al. Melatonin in plants. Nutr Rev. 2001;59(9):286-290.

51 Badria F.A. Melatonin, Serotonin, and Tryptamine in Some Egyptian Food and Medicinal Plants. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2002;5:153-157.

52 Hudson C., Hudson S.P., Hecht T., et al. Protein source tryptophan versus pharmaceutical grade tryptophan as an efficacious treatment for chronic insomnia. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8(2):121-127.

53 Herxheimer A., Petrie K.J. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (2):2002. CD001520

54 Smits M.G., van Stel H.F., van der Heijden K., et al. Melatonin improves health status and sleep in children with idiopathic chronic sleep-onset insomnia: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(11):1286-1293.

55 Garzón C., Guerrero J.M., Aramburu O., et al. Effect of melatonin administration on sleep, behavioural disorders and hypnotic drug discontinuation in the elderly: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ageing Clin Exp Res. 2009 Feb;21(1):38-42.

56 Valtonen M., Niskanen L., Kangas A.P., et al. Effect of melatonin-rich night-time milk on sleep and activity in elderly institutionalised subjects. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(3):217-221.

57 Garstang J., Wallis M. Randomised controlled trial of melatonin for children with autistic spectrum disorders and sleep problems. Child Care Health Dev. 2006 Sep;32(5):585-589.

58 Wirojanan J., Jacquemont S., Diaz R., et al. The Efficacy of Melatonin for Sleep Problems in Children with Autism, Fragile X Syndrome, or Autism and Fragile X. Syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:145-150.

59 Garfinkel D., Zisapel N., Wainstein J., et al. Facilitation of benzodiazepine discontinuation by melatonin: a new clinical approach. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Nov 8;159(20):2456-2460.

60 Peles E., Hetzroni T., Bar-Hamburger R., et al. Melatonin for perceived sleep disturbances associated with benzodiazepine withdrawal among patients in methadone maintenance treatment: a double-blind randomised clinical trial. Addiction. 2007 Dec;102(12):1947-1953. Epub 2007 Oct 4

61 Cardinali D.P., Gvozdenovich E., Kaplan M.R., et al. A double-blind-placebo-controlled study on melatonin efficacy to reduce anxiolytic benzodiazepine use in the elderly Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2002 Feb;23(1):55-60.

62 Olde Rikkert M.G., Rigaud A.S. Melatonin in elderly patients with insomnia. A systematic review. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2001 Dec;34(6):491-497.

63 Hornyak M., Voderholzer U., Hohagen F., et al. Magnesium therapy for periodic leg movements-related insomnia and restless legs syndrome: an open pilot study. Sleep. 1998;21(5):501-505.

64 Gyllenhaal C., Merritt S.L., Peterson S.D., et al. Efficacy and safety of herbal stimulants and sedatives in sleep disorders. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2000;4(3):229-251.

65. Garges H.P., Varia I., Doraiswarmy P.M. Cardiac Complications and Delirium Associated with Valerian Root Withdrawal. JAMA. 1998;280:1566-1567.

66 Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Kava extract versus placebo for treating anxiety. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (2):2002. CD003383

67 Russmann S., Lanterburg B.H., Helbling A. Kava Hepatotoxicity. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;135:68-69.

68 Escher M., Desmeulus J., Giostra E., et al. hepatitis Associated with Kava, a Herbal Remedy for Anxiety. BMJ. 2000;322(7279):139.

69 Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) Web page last updated on 21 August 2006. Available: http://www.tga.gov.au/cm/kavafs0504.htm (accessed August 2007).

70 Bent S., Padula A., Moore D., et al. Valerian for sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119(12):1005-1012.

71 Stevenson C., Ernst E. Valerian for insomnia: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Sleep Med. 2000;1:91-99.

72 Taibi D.M., Landis C.A., Petry H., et al. A systematic review of valerian as a sleep aid: safe but not effective. Sleep Med Rev. 2007 Jun;11(3):209-230.

73 Dorn M. Efficacy and tolerability of Baldrian versus oxazepam in non-organic and non-psychiatric insomniacs: a randomised, double-blind, clinical, comparative study. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2000;7:79-84.

74 Ziegler G., Ploch M., Miettinen-Baumann A., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of valerian extract LI 156 compared with oxazepam in the treatment of non-organic insomnia- a randomised, double-blind, comparative clinical study. Eur J Med Res. 2002;7(11):480-486.

75 Hallam K.T., Olver J.S., McGrath C., et al. Comparative cognitive and psychomotor effects of single doses of Valerian officinalis and triazolam in healthy volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:619-625.

76 Leathwood P.D., Chauffard F., Heck E., et al. Aqueous extract of valerian root (Valeriana officinalis L.) improves sleep quality in man. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17(1):65-71.

77 Lindahl O., Lindwall L. Double blind study of a valerian preparation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32(4):1065-1066.

78 Wheatley D. Kava and valerian in the treatment of stress-induced insomnia. Phytother Res. 2001;15(6):549-551.

79 Zanoli P., Zavatti M. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological profile of Humulus lupulus L. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008 Mar 28;116(3):383-396. Epub 2008 Jan 20

80 Fussel A., Wolf A., Brattstrom A. Effect of a fixed valerian-Hop extract combination (Ze 91019) on sleep polygraphy in patients with non-organic insomnia: a pilot study. Eur J Med Res. 2000;5:385-390.

81 Müller C.E., Schumacher B., Brattström A., et al. Life Sciences. 2002;71:1939-1949.

82 Morin C.M., Koetter U., Bastien C., et al. Valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine for treating insomnia: a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sleep. 2005 Nov 1;28(11):1465-1471.

83 Dimpfel W., Suter A. Sleep improving effects of a single dose administration of a valerian/hops fluid extract – a double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled sleep-EEG study in a parallel design using electrohypnograms. Eur J Med Res. 2008 May 26;13(5):200-204.

84 Takagi K., Saito H., Tsuchiya M. Pharmacological studies of Panax Ginseng root: pharmacological properties of a crude saponin fraction. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1972;22(3):339-346.

85 Lee S.P., Honda K., Rhee Y.H., et al. Chronic intake of panax ginseng extract stabilises sleep and wakefulness in food-deprived rats. Neurosci Lett. 1990;111(1-2):217-221.

86 Speroni E., Minghetti A. A NeuroPharmacological Activity of extracts from Passiflora Incarnata. Planta Medica. 1988;54:488-491.

87 Field T., Diego M., Cullen C., et al. Fibromyalgia Pain and Substance P Decrease and Sleep Improves After Massage Therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2002;8(2):72-76.

88 Underdown A., Barlow J., Chung V., et al. Massage intervention for promoting mental and physical health in infants aged under six months. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (4):2006. CD005038

89 Cheuk D.K.L., Yeung W.F., Chung K.F., et al. Acupuncture for insomnia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2007. Art. No.: CD005472. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005472.pub2

90 Nordio M., Romanelli F. Efficacy of wrists overnight compression (HT 7 point) on insomniacs: possible role of melatonin? Minerva Med. 2008 Dec;99(6):539-547.

91 Cerrone R., Giani L., Galbiati B., et al. Efficacy of HT 7 point acupressure stimulation in the treatment of insomnia in cancer patients and in patients suffering from disorders other than cancer. Minerva Med. 2008 Dec;99(6):535-537.

92 Lewith G.T., Godfrey A.D., Prescott P. A single-blinded, randomised pilot study evaluating the aroma of Lavandula augustifolia as a treatment for mild insomnia. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(4):631-637.

93 Thorgrimsen L., Spector A., Wiles A., et al. Aroma therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. (3):CD003150

94 American Family Physician. http://familydoctor.org/online/famdocen/home/articles/212.html Accessed October 2007.

95 Shneerson J., Wright J. Lifestyle modification for obstructive sleep apnoea. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (1):2001. CD002875

96 Lim J., Lasserson T.J., Fleetham J., et al. Oral appliances for obstructive sleep apnoea. The Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (1):2006. CD004435

97 National Health and Medical Research Council. A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 1999.