Chapter 14 Insomnia

AETIOLOGY, CLASSIFICATION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Periods of sleep disturbance due to acute stress or environmental change are common human experiences. The diagnostic DSM-IV classification of chronic primary insomnia is differentiated from an acute occurrence of insomnia, requiring the disorder to be a major health complaint, presenting with over 1 month of persistent problems in initiating or maintaining sleep, or having non-restorative sleep.1 Furthermore, for this diagnosis to be met the sleep disturbance must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational functioning, be exclusive of other disorders (such as other sleep or psychiatric disorders), and not due to medications, drugs, alcoholism or a general medical condition. Insomnia may be secondary (caused by) another medical condition, from medicines, recreational drugs or alcohol consumption, or be from environmental factors such as altitude, jet lag, poor bedding, excess light or noise. Because of this a thorough assessment is required to establish the particulars of the cause. It is estimated that 25% of chronic insomnia can be classified as ‘primary’, with approximately 75% due to the aforementioned causes.2 Interestingly, people who experience ‘transient’ insomnia (< 1 month), usually from an environmental change, acute social stressors or the loss of a loved one, usually experience daytime sleepiness during this period; a person with chronic insomnia usually does not feel sleepy, and instead may feel ‘hyperstimulated’ even after 4–6 hours’ sleep.2

Parameters measuring sleep outcomes involve evaluating total sleep time, sleep latency (how long it takes to get to sleep) and wake time after sleep onset.3 Little regard in present research is given to next-day functioning or improved outcomes in comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders. These remain areas of significance in enhancing outcomes in sleep disorders.

The prevalence of general sleep disturbance experienced by people over a year is estimated at approximately 85%, while the estimate of diagnosed chronic insomnia is estimated at around 10%.2 As in the case of other psychiatric disorders, women have a slightly higher incidence of primary insomnia.

The pathophysiology behind sleep disorders appears to involve:4–7

Prolonged poor ‘sleep hygiene’ may cause behavioural conditioning towards ‘expecting’ to have bad sleep.8 This is reflected in the fact that population surveys indicate that of the 50% of people who have sleep difficulties, between 20% and 36% report the duration is greater than 1 year.9 ‘Sleep hygiene’ is a term used to describe lifestyle interventions that assist with preparation for sleep. Aspects of good sleep hygiene focus on replacing stimulating activities with restful and quiescent activities (or non-activities) to establish a regulated circadian rhythm (this is discussed further below). Beyond the socioeconomic cost, the subjective effect of chronic sleep disturbance often involves the person experiencing a low mood or anxiety (this may not meet diagnostic threshold), fatigue or daytime somnolence, poor concentration or memory, tension headaches and digestive disturbances.10

RISK FACTORS AND ECONOMIC IMPACT

The elderly, female gender, shift workers, chronic-pain sufferers and people with co-occurring medical conditions or psychiatric disorders (especially depression and anxiety) are at greater risk of developing chronic insomnia (see the box below).4 A sedentary life and reduced exposure to sunlight may also contribute to sleep disorders. Elderly populations frequently report that they perceive a poorer quality of sleep, commonly that they have interrupted sleep, wake early or feel inadequately rested.11 Interestingly, studies show that, statistically, the elderly sleep similar hours to younger counterparts, and that the reduction of qualitative sleep experience is actually due to comorbid health issues or medications, not to do with ‘being old’.11 Chronic experience of pain increases the risk of insomnia, with a study revealing that 44% of people with chronic pain had co-existing insomnia.11 Furthermore, the more severe the level of pain was, the greater the percentage who experienced insomnia.

With respect to major depressive disorder, a study12 showed that patients with chronic insomnia had an increased risk of a major depressive disorder of 1.6 times higher than subjects with good sleep; if the insomnia was maintained for a year the risk was 40 times as high! Sleep disturbance is a frequent symptom of depression, and a strong causal link exists between insomnia and depression.11 It is likely that this is bimodal; that is, insomnia can cause depression and vice versa. Furthermore, epidemiological data have shown that approximately 40% of chronic insomniacs suffer from another comorbid psychiatric disorder.10,13 The cost that sleep disorders cause is immense, with an estimate of direct cost of insomnia in the United States of America approximating US$13.93 billion in 1999.14 Interestingly, most of this cost was service-based (especially for nursing home costs) and only a fraction was from

prescriptive costs. While prescriptive drug use is prevalent in insomniacs for the treatment of the disorder, medications for other conditions may also cause insomnia (see the box above).11,15

It should be noted that while the previously mentioned risk factors may cause sleep disorders chronic sleep disturbances may also in turn cause a variety of physical and mental conditions.9,17 The most concerning link with chronic insomnia is that evidence indicates that people with poor sleep or < 6 hours per night have a significantly greater risk of: 3

Sleep disorders and headaches

Sleep, or lack thereof, is regarded as being able to both provoke and relieve headache.18 Epidemiological research has associated sleep disorders with more frequent and severe headaches. Clinical research correlates specific headache diagnoses with chronobiological sleep-pattern disturbance, implicating similar neurochemical processes between the two disorders.19 Chronic daily morning headache patterns are particularly suggestive of sleep disorders, including sleep-related breathing disorders, insomnia, circadian rhythm disorders and parasomnias.18

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Sage advice when treating transient insomnia should be to establish the underlying causes, initiate good sleep hygiene changes, commence (or refer) an appropriate psychological intervention and offer lifestyle and prescriptive advice.15 The medical ‘quick fix’ is usually the use of pharmaceutical hypnotics as the primary first-line pharmacotherapy to treat chronic insomnia.20 The use of benzodiazepines such as diazepam (or its metabolites) or non-benzodiazepine hypnotics such as zolpidem or zopiclone are preferred currently over older barbiturates which can cause death in cases of overdose.20 Although benzodiazepines are relatively safe medications, concerns exist over dependency, and currently most guidelines endorse only short-term use.21

Sedating antidepressants, for example mirtazepine or fluvoxamine, may also be prescribed, especially in cases of comorbid depression.20 In some cases the use of sedating antipsychotic or tricyclic medication may also be employed. Opiates also have soporific effects, and may be indicated in cases of chronic pain with insomnia. Melatonin (an endogenous hormone secreted by the pineal gland) is also prescribed in some countries, especially to treat sleep disturbance, especially if caused by jet lag.22 A novel

melatoninergic agent called agomelatine, a melatonin 1,2 receptor agonist and serotonin 5HT2c receptor agonist (at stage IV clinical trials), may in the future be used as a non-addictive hypnotic with anxiolytic properties.25 Referral for psychological interventions such as cognitive modification or behavioural adjustments may also be recommended in primary care.26

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

Circadian rhythm modulation

The primary circadian ‘clock’ in humans is located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei in the hypothalmus; these cells govern the daily biological rhythm over a cycle lasting approximately 24 hours and 11 minutes.5 The wake/sleep cycle is influenced externally by light and dark, with exposure to light increasing the secretion of serotonin, while darkness increases the secretion of melatonin. The circadian rhythm governs internal temperature changes, sleep and eating patterns. Human clock genes have been identified as being involved with various sleep disorders.5 Future gene therapy may target the expression of these clock genes to effectively reset the circadian rhythm. In the meantime, the use of interventions that modulate the circadian rhythm and the use of sleep hygiene techniques such as ‘sleep restriction’ and ‘light therapy’ may assist in readjusting the circadian rhythm.

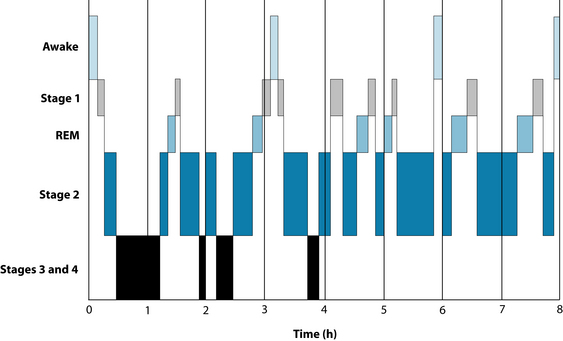

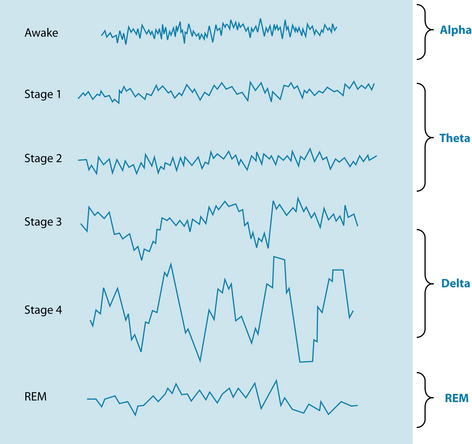

Another neurological factor involved in sleep is the endogenous compound adenosine. This inhibitory compound and the adenosine receptor binding sites are a homeostatic sleep factor responsible for mediating the REM cycle (see Figures 14.1 and 14.2).27 Adenosine can potently inhibit cholinergic neurons that are involved with cortical arousal, and during periods of prolonged wakefulness adenosine accumulates in certain parts of the brain and promotes the transition from a wake state to a sleep state.7 This is considered to be one of the factors involved in the theory of ‘sleep debt’, in which sleep deprivation over days accrues a chronological sleep debt (a build-up of adenosine), which then prompts a period of increased sleep to make up for loss. Caffeine antagonises adenosine receptors, thereby increasing wakefulness (see the lifestyle advice section below).28 The compound adenosine would appear to be a potential hypnotic substance; as discussed above, endogenous adenosine is responsible for modulating the wake-sleep cycle via binding to adenosine (A1) and (A2) receptors. A literature search reviewing clinical evidence of this product revealed no clinical evidence, however; this remains an area of potential exploration.

Humulus lupulus is used in Europe extensively in sleep formulations to promote sleep. The bitter herb is regarded by the eclectics as a useful remedy for imparting sedative and hypnotic actions.29 While animal and in vitro models do not currently support sedative or anxiolytic activity, hypnotic effects involving melatoninergic and GABAergic modulation have been documented.30 Humulus lupulus combines well with Valeriana spp. root, demonstrated by a fixed valerian–hop combination (Ze 91019) found to reduce sleep latency and waking time compared to placebo in 30 subjects after 2 weeks of treatment.31 Another randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing the combination to placebo and diphenhydramine revealed less conclusive results.32 The 4-week study involving 184 adults with mild insomnia showed none or only minor improvements of subjective sleep parameters compared to placebo, with most outcomes being similar between all three groups. It is possible that the inclusion of ‘mild’ insomniacs diluted the response from the herbal combination. In vitro studies indicate that hops–valerian preparations invoke hypnotic activity via agonising adenosine, melatonin and serotonin receptors.33–35

Valeriana officinalis has a rich folkloric tradition of use in conditions of restlessness, hysteria, nervous headache and mental depression,29,36 with Pliny regarding the powder of the root as effective in cases of spasms causing pain.37 Energetically Valeriana spp. root was regarded by Dioscorides as possessing warming properties;37 this is reflected in the pungent aroma of the essential oils (valerenal, iso/valerianic acid) and terpenes (valerenic acid).38 The use of Valeriana spp. in prescriptions needs to be monitored due to this ‘heating ’ effect, which can evoke stimulation and restlessness (the eclectics classified valerian as a ‘cerebral stimulant’).29,39 A systematic review and meta-analysis included 16 eligible RCTs involved a total of 1093 patients.38 The results revealed that on six studies with a dichotomous outcome of sleep quality (‘improved’ or ‘not improved’) a statistically significant benefit occurred. Nine out of 16 studies did not, however, have positive outcomes in regard to improvement of sleep quality. It should be noted that many studies included in the review involved combinations of valerian with other herbal medicines (for example Piper methysticum or H. lupulus), differing outcome scales, dosages and participant populations, and eight trials had small sample sizes. Because of this, currently the evidence does not firmly support the use of valerian as a stand-alone hypnotic.

A 2001 clinical trial demonstrated that V. edulis improved sleep architecture over V. officinalis by diminishing waking episodes and improving delta sleep.40 This is an important difference with respect to addressing ‘maintenance insomnia’. Valeriana spp. have demonstrated some clinical evidence in enhancing sleep parameters when used for periods of >2 weeks, and acute administration appears to have only minor effect.31,41,42 The mechanism of action regarding Valeriana spp. hypnotic effect is posited as involving an increase in REM stage and delta sleep,40,41 mediated by GABA-A receptor (β3 subunit) agonism,43 and adenosine 1, benzodiazepine and serotonin 5-HT (1A) receptor agonism.33,35,44 Commission E and the World Health Organization support the use of valerian for restlessness and sleep disorders,45 but more robust clinical trials are required to provide firm endorsement.

Vitex agnus-castus, although used commonly for hormonal and menstrual irregularities,46 may exert a novel melatoninergic activity. While to date no human clinical trials exist testing V. agnus-castus in insomnia, a study of 20 healthy human males demonstrated a significant dose-dependent increase of melatonin secretion using 120 mg, 240 mg, 480 mg of the extract per day compared to placebo for 14 days.47

Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) hyperarousal

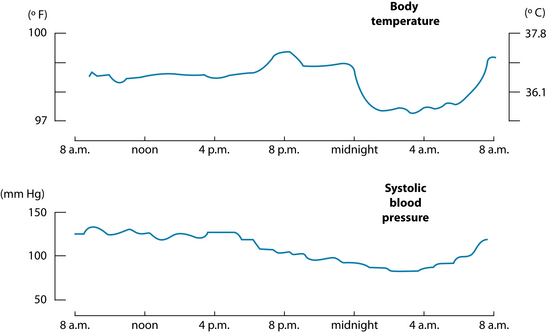

Chronic primary insomnia has been characterised by a state of biopsychological arousal, which is counter to a lowering of body temperature, blood pressure and cortisol (see Figure 14.3).4 Elevations of circulating catecholamines, adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol production, raised metabolic rate and core body temperature and overactive beta EEG frequency have been documented in this hyperstimulated state responsible for chronic insomnia.4 Interestingly, this mirrors various presentations of melancholic depression (anxiety, psychosocial unresponsiveness and early morning waking), and the common link (an overactive HPA axis) could explain the link between depression and insomnia (see the depression chapter, and Section 5 on the endocrine system).13,48 Herbal medicines that regulate HPA-axis activity and exercise may have role in treating insomnia. Withania somnifera is regarded as an anxiolytic, adaptogen and nervine trophorestorative, used to assist in reducing mental tension and revitalise body/mind.49 W. somnifera is classed as a ‘rasayana’ in Ayurvedic medicine, and is used to promote physical and mental health.50 Animal studies have confirmed its efficacy in the treatment of chronic stress and anxiety,50,51 with the glycowithanolides regarded as the active constituents, exerting a GABA-mimetic activity.49,50 To date no RCTs exist examining the herb for use in insomnia, so caution should be adopted when extrapolating from the minor in vitro and in vivo evidence. Other herbal medicines that may exert a HPA-axis modulating effect include Rhodiola rosea, Panax ginseng (its use in the evening due to its stimulatory properties should be limited) and Eleutherococcus senticosus.39,52

Exercise and physical activity are advised to assist in balancing the function of the HPA axis. Regular graded physical exercise may promote relaxation and raise core body temperature, this activity potentially benefiting the sleep pattern.53 Exercise also addresses weight gain and obesity, which are factors that increase the occurrence of sleep disorders. A Cochrane review found that, in one trial involving a sample of 43 elderly participants with insomnia, exercise improved sleep onset latency, total sleep and quality of sleep.54

The GABAergic system

As discussed previously in the anxiety case, GABA has a role in the inhibitory effect on neurological activity by attenuating hyperarousal in both mood and sleep disturbance. GABA-α receptors play a crucial role in the initiation and maintenance of non-REM sleep (deep sleep).6 Furthermore, in cases of comorbid anxiety, interventions that modulate GABA activity may have a role in reducing anxiety, which in turn may ameliorate insomnia. The use of GABA modulating phytotherapies such as Scutellaria lateriflora, Passiflora incarnata and Piper methysticum may be of benefit in treating insomnia. S. lateriflora was regarded by eclectic physicians and physiomedicalists as a ‘truly valuable medicine’ used to treat nervous excitability, restlessness or wakefulness (see the anxiety chapter for evidence).29,36 P. incarnata has a history of use by. Europeans and Native Americans for its hypnotic and anxiolytic action (see the anxiety chapter for evidence).29 It should be noted that while both S. lateriflora and P. incarnata have documented anxiolytic activity, it does not necessarily confer a hypnotic effect. The use of the herbs may play an adjuvant synergistic role with hypnotic interventions, especially if comorbid anxiety is apparent.

P. methysticum is a well documented GABA-modulator that has solid evidence as an effective anxiolytic. It may be of benefit in anxious insomnia, and to date one specific study has examined the plant in this presentation. A 4-week RCT using 200 mg of a standardised extract of kava in 61 patients explored the effect on anxious participants with comorbid insomnia.55 Via a sleep questionnaire, the results revealed that, compared to placebo, the extract improved the quality of sleep and the recuperative effect after sleep. A 5-week RCT has also been conducted to explore the use of P. methysticum on benzodiazepine withdrawal. A standardised WS® 1490 P. methysticum extract was used on 40 subjects with chronic anxiety and a long history of benzodiazepine use.56 Subjects were tapered off their benzodiazepines over the first 2 weeks, while the kava was titrated from 50 mg up to 300 mg by the end of week 1. P. methysticum produced a statistically significant reduction in anxiety on the Hamilton anxiety scale57 (a 7.5 point decrease over placebo at week 5), and the Benfindlichkeits-Skala subjective wellbeing scale.58 Importantly, aside from some subjects experiencing withdrawal symptoms, no negative reactions (such as increased sedation) occurred during the first week of adjuvant P. methysticum use. Furthermore, five subjects in the P. methysticum group displayed adverse symptoms from benzodiazepine withdrawal compared with 10 in the placebo group. During a follow-up study, nine out of 14 subjects who were switched from P. methysticum to placebo experienced recurrence of anxiety. A qualitative study conducted by Sarris et al. (2009: in submission) exploring the experiences of people taking kava in a clinical trial revealed that in addition to the plant improving participants’ mood and anxiety levels, some participants detailed beneficial effects on sleep markers.

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

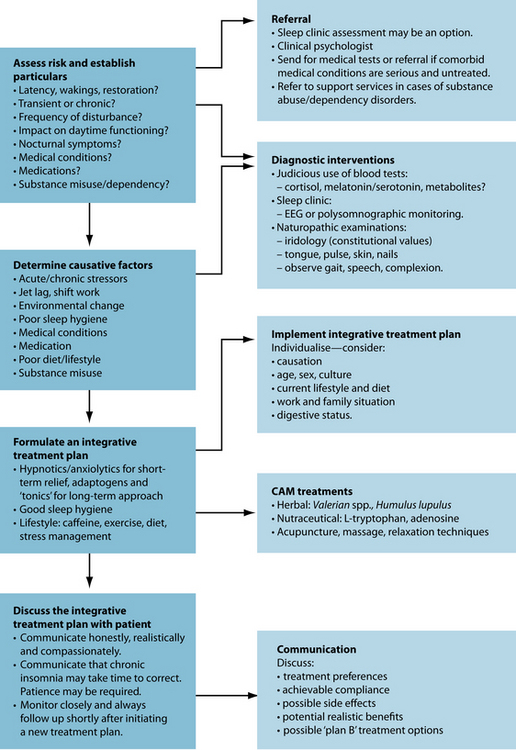

Various integrative options exist for treating insomnia. Referral for appropriate psychological interventions and for an exercise program or relaxation techniques (and possibly acupuncture) may be of assistance. Sleep clinics are usually available in large cities. These

SLEEP APNOEA AND SNORING59

clinics may perform EEG tests observing the person’s sleep latency and arousal level during sleep, and other nocturnal factors such as sleep apnoea. Sleep hygiene techniques may also be taught at these clinics.

Psychological intervention

A review of the psychological and behavioural treatments of insomnia by Morin et al.26 of 37 controlled studies involving 2246 subjects concluded that these techniques produced reliable changes in several sleep parameters, and that these improvements were well-sustained over time. Five main evidence-based psychological and behavioural treatments exist in the management of insomnia:

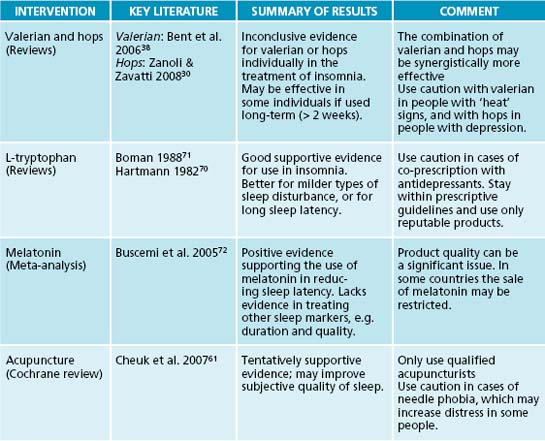

Acupuncture

A Cochrane review and meta-analysis of acupuncture and acupressure in the treatment of insomnia has been conducted.61 Seven trials met sufficient methodological rigour for inclusion and included 590 participants. Conventional needle acupuncture, acupressure, auricular magnetic and seed therapy, and transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation were evaluated. Results revealed that acupuncture and acupressure may help to improve sleep quality scores when compared to control or compared to no treatment. The authors note that the efficacy of acupuncture or its variants was inconsistent between studies for many sleep parameters, such as sleep onset latency, total sleep duration and wake after sleep onset. The combined result from three RCTs evaluating subjective insomnia improvement, however, revealed that acupuncture or its variants was no more effective than control. Although promising, the small numbers of heterogenous and methodologically poor RCTs do not strongly support the use of any form of acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia.

Case Study

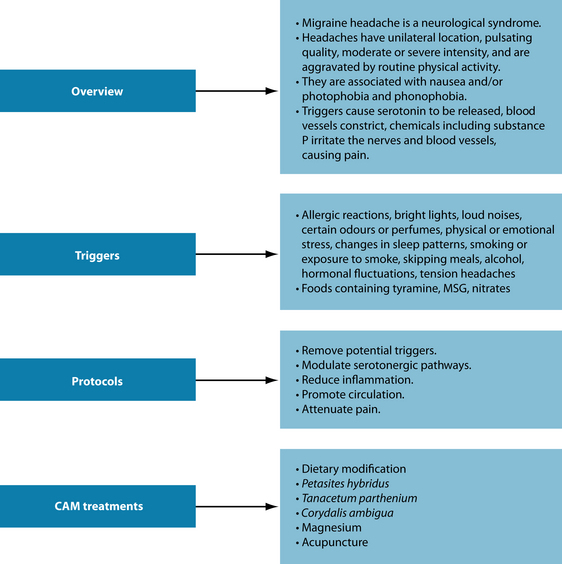

A 62-year-old male reports that his sleeping pattern is poor. He has a long sleep latency (1 hour to get to sleep) and wakes during the night. He has a stressful job and present relationship difficulties. Due to getting only between 5 and 6 hours sleep per night he is drinking coffee throughout the day to stay awake. Complicating matters, he also complains that he suffers from regular migraine headaches, which he says affects his sleep (see Figure 14.5).

Example treatment

Herbal and nutritional prescription

As part of an integrative approach, the use of hypnotic, anxiolytic and adaptogenic actions in the formula should aid in the restoration of sleep. Withania somnifera is prescribed as a sedative and adaptogen; Valeriana officinalis, Humulus lupulus and Vitex agnus-castus are prescribed to exert a hypnotic activity.30,38,39 The use of two doses in the evening is important. The initial dose will exert a hypnotic and anxiolytic effect that will prepare the body/mind for sleep. The next dose 1 hour before sleep will boost serum levels of the constituents, and in combination with good sleep hygiene techniques should facilitate sleep. Although currently only possessing theoretical evidentiary support, the use of adenosine phosphate tablets may aid in the modulation of the circadian rhythm.27 The use of L-tryptophan or melatonin may also be options (see ‘Additional therapeutic options’ below).

Herbal formula

| Withania somnífera 1:1 | 30 mL |

| Valeriana officinalis 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Passiflora incarnata 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Humulus lupulus 1:2 | 15 mL |

| Vitex agnus-castus 1:2 | 10 mL |

| 7.5 mL b.d. | 100 mL |

| (early evening and 1 hour before bedtime) | |

To address his migraines, as detailed in Figure 14.5, the implementation of a diet reducing the consumption of common food triggers (such as dietary amines, MSG and nitrates) may be of benefit. Magnesium may be beneficial in reducing the frequency of the attacks.62 Tanacetum parthenium has a history of traditional use for the treatment of migraine. While this may be a potential therapeutic option for the patient, two RCTs have revealed no efficacy in treating migraine headaches beyond placebo.63

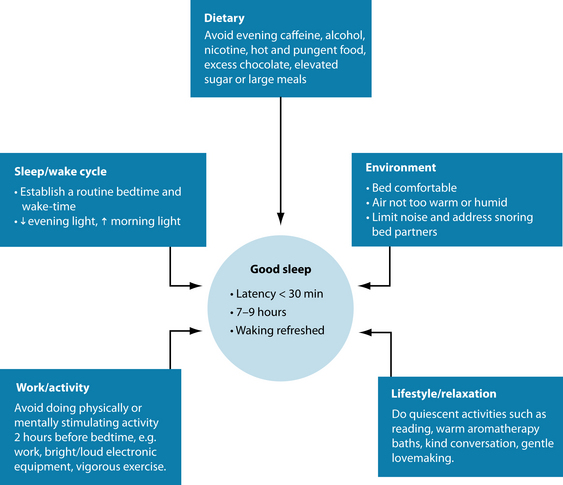

Sleep hygiene and dietary and lifestyle advice

General lifestyle advice should focus on good sleep hygiene techniques (see Figure 14.6).8 The key techniques revealed by sleep researchers focus primarily on limiting exposure to the bed (sleep restriction)—that is, the patient having only a limited time to sleep, and getting up at a set time in the morning regardless of quality or quantity of sleep.8 This should in time regulate the circadian rhythm. Patients should also be advised not to ‘force’ sleep. If sleep does not occur within 20 minutes, then they should get up and focus the mind on an activity until they feel tired (still minimising light and mental activity). The other mainstay is to reduce exposure to light prior to sleep, and increase exposure to morning sunlight upon waking. It is also best to avoid excessive daytime naps as this may disturb the circadian rhythm.

Further sleep hygiene advice includes stimulus control: avoidance of stimulating activity and stimulants close to sleep (for example, smoking, caffeine and stimulating TV or books),66 and adequate sleep preparation (for example, aromatherapy baths, relaxing reading material, gentle lovemaking and positive calming mental cognition). Avoidance of excess energetically ‘heating’ foods (such as alcohol, garlic, chillies and curries) may also be of assistance,67 while the diet (or supplementation) may provide the nutrients required for the creation and regulation of adrenal hormones and psychoactive neurotransmitters (B vitamins, magnesium, calcium and vitamin C) helps support healthy functioning of the nervous system.68 Although evening meal portions should not be excessive (this may cause rebound hypoglycaemia), sufficient calorific intake is required to avoid waking up due to hunger. Some people find a warm milk drink helpful in initiating sleep; this may be due to the effect of calcium.69 Finally, moderating a busy work schedule is desirable to allow for regular exercise and relaxation to reduce stress levels.

The most obvious advice is to cut down or eliminate caffeine consumption. Caffeine is antagonistic to adenosine receptors and will interfere with circadian rhythm.28 The half-life of caffeine is approximately 4–6 hours and in women taking the oral contraceptive pill it may be greatly increased (see the anxiety chapter for more detail).28 Pharmacokinetically, the caffeine from a cup of coffee drunk at 1 p.m can be still in the system by sleep time at 11 p.m., so avoidance of caffeine after lunch may be prudent. Patients may also be advised to keep a sleep diary over 2 weeks to record their sleep patterns. This may provide more diagnostic detail, and allow for a more thorough critique of their sleep hygiene. A ‘worry diary’ can also be an added component, with patients writing down before they sleep anything on their minds. This technique may help the person ‘let go’ of these concerns, leaving them on paper to be addressed the following day.

With respect to dietary change to address his migraines, various potential ‘migraine-triggering’ food groups can be removed and re-challenged (see Chapter 5 on food intolerance). Below is a list of common culprits that may provoke a migraine attack:

Additional therapeutic options

recommended dosage should not present with any high level of risk (see a health professional for exact prescriptive advice).

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

In the above case the patient’s insomnia is expected to be ameliorated within the week. Chronic insomniacs have a poor prognosis and the prognosis is worse if it is complicated by comorbid mental disorders and substance abuse.74 An integrative approach involving sleep hygiene education, psychological, dietary/nutraceutical, lifestyle and herbal intervention should offer a sustained benefit if compliance is maintained. If after 2 weeks of the prescription minimal benefit has occurred, the herbal prescription can be modified to include other hypnotics and anxiolytics such as Eschscholzia californica, Melissa officinalis and Bacopa monnieri.29,75 Melatonin or L-tryptophan may also be used if the patient is non-responsive to the initial prescription. Additional psychological interventions (behavioural or social-based models) may also be of assistance to examine and aid in the management of the external triggers of the stress and insomnia. The key is to advise the person to be patient and not to ‘force’ the sleep process, to be disciplined if following sleep restriction techniques (no daytime napping and a regular waking time), maintain good sleep hygiene and try to address any psychosocial social factors impacting sleep. With regard to the patient’s migraines, his headaches may take longer to abate, and if no change was occurring after several weeks of treatment with dietary adjustment and herbal and nutritional prescription, use of Tanacetum parthenium and Petasites hybridus and referral for acupuncture may be advised. It is likely that the migraines will be mitigated when the patient’s sleep pattern improves.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Roth T., Roehrs T. Insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequences. Clinical Cornerstone: Chronic Insomnia. 2003;5(3):5-15.

3. Krystal A.D., Roth T. Definitions, measurements, and management in insomnia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:5-7.

4. Roth T., et al. Insomnia: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2007;11(1):71-79.

5. Piggins H.D. Human clock genes. Annals of Medicine. 2002;34(5):394-400.

6. Lancel M. Role of GABA(A) receptors in the regulation of sleep: initial sleep responses to peripherally administered modulators and agonists. Sleep. 1999;22(1):33-42.

7. Strecker R.E., et al. Another chapter in the adenosine story. Sleep. 2006;29(4):426-428.

8. Stepanski E.J., Wyatt J.K. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2003;7(3):215-225.

9. Krystal A.D. The changing perspective on chronic insomnia management. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:20-25.

10. Roth T. Measuring treatment efficacy in insomnia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:8-12.

11. Benca R.M. Special considerations in insomnia diagnosis and management: depressed, elderly, and chronic pain populations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:26-35.

12. Ford D., Kamerow D. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479-1484.

13. Roth T. Insomnia as a risk factor for depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;7:S34-S35.

14. Walsh J.K. Clinical and socioeconomic correlates of insomnia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:13-19.

15. Ramakrishnan K., Scheid D.C. Treatment options for insomnia. American Family Physician. 2007;76(4):517-526.

16. Sateia M.J., et al. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2000;23(2):243-308.

17. Sateia M.J., Nowell P.D. Insomnia. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1959-1973.

18. Rains J.C., et al. Sleep and headaches. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(2):167-175.

19. Rains J.C., Poceta J.S. Headache and sleep disorders: review and clinical implications for headache management. Headache. 2006;46(9):1344-1363.

20. Tariq S.H., Pulisetty S. Pharmacotherapy for insomnia. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2008;24(1):93-105.

21. Rickels K., Rynn M. Pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 14):9-16.

22. Cajochen C., et al. Role of melatonin in the regulation of human circadian rhythms and sleep. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2003;15(4):432-437.

23. Schwartz J.R., Roth T. Shift work sleep disorder: burden of illness and approaches to management. Drugs. 2006;66(18):2357-2370.

24. Hein H. [The sleep apnoea syndromes: alternative therapies]. Pneumologie. 2004;58(5):325-329.

25. Lemoine P., et al. Improvement in subjective sleep in major depressive disorder with a novel antidepressant, agomelatine: randomized, double-blind comparison with venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1723-1732.

26. Morin C.M., et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998–2004). Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398-1414.

27. Basheer R., et al. Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation. Prog Neuropsychobiol. 2004;73:379-396.

28. Nehlig A., et al. Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1992;17(2):139-170.

29. Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American dispensatory. Online. Available: http://www.henriettesherbal.com/eclectic/kings/extracta

30. Zanoli P., Zavatti M. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological profile of Humulus lupulus L. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116:383-396.

31. Fussel A., et al. Effect of a fixed valerian-hop extract combination (Ze 91019) on sleep polygraphy in patients with non-organic insomnia: a pilot study. Eur J Med Res. 2000;5(9):385-390.

32. Morin C., et al. Valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine for treating insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1465-1471.

33. Abourashed E.A., et al. In vitro binding experiments with a valerian, hops and their fixed combination extract (Ze91019) to selected central nervous system receptors. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(7–8):633-638.

34. Muller C.E., et al. Interactions of valerian extracts and a fixed valerian-hop extract combination with adenosine receptors. Life Sci. 2002;71(16):1939-1949.

35. Schellenberg R., et al. The fixed combination of valerian and hops (Ze91019) acts via a central adenosine mechanism. Planta Med. 2004;70(7):594-597.

36. Cook W. The physiomedical dispensatory. Online. Available: http://www.ibiblio.org/herbmed/eclectic/cook/main.htm. Accessed 10 October 2005.

37. Culpeper N. Culpeper’s complete herbal. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd; 1652.

38. Bent S. Valerian for sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119:1005-1012.

39. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

40. Herrera-Arellano A., et al. Polysomnographic evaluation of the hypnotic effect of Valeriana edulis standardized extract in patients suffering from insomnia. Planta Med. 2001;67(8):695-699.

41. Donath F., et al. Critical evaluation of the effect of valerian extract on sleep structure and sleep quality. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33(2):47-53.

42. Gutierrez S., et al. Assessing subjective and psychomotor effects of the herbal medication valerian in healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78(1):57-64.

43. Benke D., et al. GABA(A) receptors as in vivo substrate for the anxiolytic action of valerenic acid, a major constituent of valerian root extracts. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):174-181.

44. Schumacher B., et al. Lignans isolated from valerian: identification and characterization of a new olivil derivative with partial agonistic activity at A(1) adenosine receptors. J Nat Prod. 2002;65(10):1479-1485.

45. Blumenthal M., editor. The ABC clinical guide to herbs. Austin: American Botanical Council, 2004.

46. Wuttke W., et al. Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus) – pharmacology and clinical indications. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(4):348-357.

47. Dericks-Tan J.S., et al. Dose-dependent stimulation of melatonin secretion after administration of agnus castus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003;111(1):44-46.

48. Ayuso-Gutierrez J.L. Depressive subtypes and efficacy of antidepressive pharmacotherapy. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2005;6(Suppl 2):31-37.

49. Mishra L.C., et al. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Withania somnifera (ashwagandha): a review. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(4):334-346.

50. Bhattacharya S.K., et al. Anxiolytic-antidepressant activity of Withania somnifera glycowithanolides: an experimental study. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(6):463-469.

51. Bhattacharya S.K., Muruganandam A.V. Adaptogenic activity of Withania somnifera: an experimental study using a rat model of chronic stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75(3):547-555.

52. Kelly G.S. Rhodiola rosea: a possible plant adaptogen. Altern Med Rev. 2001;6(3):293-302.

53. Atkinson G., Davenne D. Relationships between sleep, physical activity and human health. Physiol Behav. 2007;90(2–3):229-235.

54. Montgomery P., Dennis J. Physical exercise for sleep problems in adults aged 60+. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2002. CD003404

55. Lehrl S. Clinical efficacy of kava WS 1490 in sleep disturbances associated with anxiety disorders. Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:101-110.

56. Malsch U., Kieser M. Efficacy of kava-kava in the treatment of non-psychotic anxiety, following pretreatment with benzodiazepines. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;157:277-283.

57. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50-55.

58. CIPS. Internationale Skalen fur die Psychiatrie. Gottingen: Beltz; 1996.

59. Malhotra A., White D.P. Obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):237-245.

60. Puhan M.A., et al. Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 4. 2006;332(7536):266-270.

61. Cheuk D.K.L., et al. Acupuncture for insomnia. Cochrane Database syst Rev. (3):2007;. CD005472

62. Rios J., Passe M.M. Evidenced-based use of botanicals, minerals, and vitamins in the prophylactic treatment of migraines. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2004;16(6):251-256.

63. Pittler M.H., et al. Feverfew for preventing migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2000;. CD002286

64. Silberstein S.D. Migraine. Lancet. 2004;363(9406):381-391.

65. Griggs C., Jensen J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine: critical literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(4):491-501.

66. Jefferson C.D., et al. Sleep hygiene practices in a population-based sample of insomniacs. Sleep. 2005;28(5):611-615.

67. Maciocia G. The foundations of Chinese medicine. Singapore: Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

68. Haas E.M. Staying healthy with nutrition. Berkeley: Celestial Arts; 1992.

69. Werbach M. Nutritional influences on illness, 2nd edn. Tarzana: Third Line Press; 1996.

70. Hartmann E. Effects of L-tryptophan on sleepiness and on sleep. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(2):107-113.

71. Boman B. L-tryptophan: a rational anti-depressant and a natural hypnotic? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1988;22(1):83-97.

72. Buscemi N., et al. The efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for primary sleep disorders. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1151-1158.

73. Lazic S.E., Ogilvie R.D. Lack of efficacy of music to improve sleep: a polysomnographic and quantitative EEG analysis. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;63(3):232-239.

74. Nutt D., et al. Generalized anxiety disorder: a comorbid disease. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(Suppl 2):S109-S118.

75. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs: herbal formulations for the individual patient. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.