INSECT AND ARTHROPOD BITES

BEES, SPIDERS, SCORPIONS, AND OTHER SMALL BITERS

Bees, Wasps, Hornets, and Ants

“Killer bees” are an Africanized race of honeybees created by interbreeding of the African honeybee Apis mellifera scutellata (brought for experiments into Brazil) with common European honeybees. The hazard from these bees is that they tend to be more irritable, sense threat at a distance greater than their European counterparts, swarm more readily, defend their nests more aggressively and stay agitated around the nest for days, and impose mass attacks on humans. The venom of an Africanized bee is not of greater volume or potency than that of a European honeybee. However, the personality of the Africanized bees is such that they may pursue a victim for up to ⅔ mile (1 km), and may recruit other attacking bees by the hundreds or thousands. A victim may be stung from 50 to more than 1,000 times; it is estimated that 500 stings achieves the lethal threshold. The bees are established in Arizona, New Mexico, and California, and unfortunately appear to be increasing their habitat as they adapt to colder temperatures.

Treatment for Insect Sting

1. Be prepared to deal with a severe allergic reaction (see page 66). If the victim develops hives, shortness of breath, and profound weakness, and appears to be deteriorating, immediately administer epinephrine. This is injected subcutaneously (see page 474) in a dose of 0.3 to 0.5 mL for adults and 0.01 mL/kg (2.2 lb) of body weight for children, not to exceed 0.3 mL. Epinephrine is available in allergy kits with instructions for use. Anyone known to have insect allergies who travels in the wilderness should carry epinephrine. Take particular care to handle preloaded syringes carefully, to avoid inadvertent injection into a finger. When administering an injection, never share needles between people.

The drug is available in preloaded syringes in certain allergy kits, which include the EpiPen autoinjector and EpiPen Jr. autoinjector (Dey), the Twinject autoinjector (Verus: 0.3 mg or 0.15 mg doses; 2 doses per unit), and the Ana-Kit. Instructions for use accompany the kits. The EpiPen and Twinject epinephrine products are generally easier for laypeople to use, because they require less dexterity to accomplish injection with them. The Twinject autoinjector and Ana-Kit syringe are configured with enough epinephrine for a second (repeat) dose, which is sometimes necessary. The Twinject is a true autoinjector for the first dose; the second dose is delivered as a routine injection from a concealed syringe and needle.

2. Administer diphenhydramine (Benadryl) by mouth, 50 to 100 mg for an adult and 1 mg/kg (2.2 lb) of body weight for a child. This antihistamine drug may by used by itself for a milder allergic reaction. Topical antihistamine lotions or creams may be beneficial.

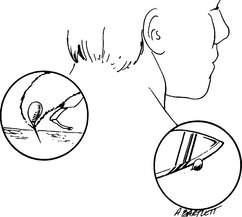

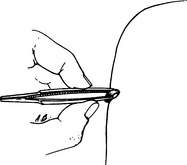

3. Stingers or pieces of stingers left in the skin should be removed as quickly as possible (Figure 203). It used to be taught that pulling the stinger out with fingers or forceps squeezed more venom into the victim, but this is currently not believed to be true. So, it is better to flick or pull a stinger and venom sac out of the skin of the victim using tweezers or your fingers than to waste precious time searching for a straight-edged object, such as a knife or credit card, to scrape away the stinger. Furthermore, crude scraping runs the risk of breaking off the stinger and leaving it embedded in the skin. An alternative is to try to pull out the stinger, then apply the Extractor device (Figure 204), if you are carrying one and it is available immediately after the sting has occurred.

4. Apply ice packs to the site of the sting.

5. Home topical remedies, such as aspirin, a 20% aluminum salt-containing preparation (including many household antiperspirants), or paste of baking soda or papain-containing meat tenderizer (such as Adolph’s unseasoned meat tenderizer) and water directly to the wound (for no more than 15 minutes), are of unproven value. Do not apply mud. The commercial product After Bite (Tender Corporation), a mixture of ammonium hydroxide and mink oil, is moderately effective for relief of pain and itching following insect bites, but will not abort an allergic reaction. StingEze liquid (Wisconsin Pharmacal) is a mixture of camphor, phenol, benzocaine, and diphenhydramine. This is a good agent to control itching and mild pain following any insect bite. Lidocaine 4% applied topically may help diminish discomfort.

6. If a person suffers an extensive skin and soft tissue reaction (swelling, itching, blisters), he may benefit from the administration of a corticosteroid, such as prednisone (60 mg by mouth day one, tapered by 10 mg per day over the next 5 days) or methylprednisolone (24 mg by mouth day one, tapered over the next 5 days).

7. If a person stung by an insect develops more than a mild to moderate local reaction, transport him to a hospital.

8. A bee sting in general does not pose a large risk for tetanus infection. Although deep punctures of other varieties deposit bacteria into the wound(s), where C. tetani can thrive in the absence of oxygen, a bee sting puncture isn’t that deep. The stinger might transfer bacteria from the skin surface, wherein lies the greatest risk. If a person has been immunized within the past 5 years, it is unnecessary to get a Td (or Tdap) booster immunization. If it has been more than 5 years but less than 10 years since the last tetanus shot, a Td (or Tdap) booster is indicated. If it has been more than 10 years since the last tetanus shot, both a Td (or Tdap) booster and tetanus immune globulin are indicated, if you go by the book.

Avoidance of Stinging Insects

1. Store garbage, particularly fruit, at a distance from the campsite.

2. Remove (carefully) beehives and wasp nests from children’s play areas.

3. Wear light-colored clothing. Dark-colored clothing is attractive to insects and may evoke a defensive (sting or bite) response. Keep shirt sleeves closed and tuck pants into boots. Wear light-colored socks.

4. Avoid wearing sweet fragrances that make you smell like a flower.

5. Do not anger bees or wasps. If confronted by a swarm, cover your face (eyes, nose, and mouth) and move rapidly from the area. If necessary, throw a blanket or towel over your head. Run if you must. Run through bushes or weeds to confuse the bees. Don’t jump into a pool—the bees may wait for you and a severe allergic reaction from a sting while in the water may be extremely dangerous. Do not poke sticks or throw rocks into bee holes.

6. Avoid rapid or jerky movements near bees. Do not swat at them.

SPIDERS

Black Widow Spider

In the United States, the female black widow spider (Latrodectus mactans) is about ⅝ in (15 mm) in body length, black or brown, and with a characteristic red (or orange or yellow) hourglass marking on the underside of the abdomen (Figure 205). The top side of the spider is shiny and features a fat abdomen that resembles a large black grape. The longest legs are directed toward the front. This species and other Latrodectus species are found scattered in rural regions, in barns, within harvested crops, and around outdoor stone walls. Some are arboreal.

Figure 205 Female black widow spider with typical hourglass marking on the underside of the abdomen.

The bite of the black widow spider is rarely very painful (usually more like a pinprick) and often causes little swelling or redness, although there can be a warm and reddened area around the bite. If much venom has been deposited, the victim develops a typical reaction well within an hour. Symptoms include muscle cramps, particularly of the abdomen and back; muscle pain; muscle twitching; numbness and tingling of the palms of the hands and bottoms of the feet; headache; droopy eyelids; facial swelling; drooling; sweating; restlessness and anxiety; vomiting; chest muscle spasms, causing difficulty in breathing; fever; and high blood pressure. A man may develop a persistent penile erection (priapism). A small child may cry persistently. A pregnant woman may develop uterine contractions and premature labor.

Treatment for a Black Widow Spider Bite

1. Apply ice packs to the bite.

2. Immediately transport the victim to a medical facility.

3. Once the victim is in the hospital, the doctor will have a number of therapies to use, which include intravenous calcium solutions and muscle relaxant medicines for muscle spasm; antihypertensive drugs for elevated blood pressure; pain medicine; and, in very severe cases, antivenom to the venom of the black widow spider.

4. If you will be unable to reach a hospital within a few hours and the victim is suffering severe muscle spasms, you may administer an oral dose of diazepam (Valium), if you happen to be carrying it. The starting dose for an adult who does not regularly take the drug is 5 mg, which can be augmented in 2.5 mg increments every 30 minutes up to a total dose of 10 mg, so long as the victim remains alert and is capable of normal, purposeful swallowing. The starting dose for a child age 2 to 5 years is 0.5 mg; for a child age 6 to 12 years the starting dose is 2 mg. Total dose for a child should not exceed 5 mg; never leave a sedated child unattended.

Brown Recluse Spider

At least five species of recluse spiders are found in the United States. The brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is the best known and found most commonly in the South and southern Midwest. However, interstate commerce has created habitats in many other parts of the country for the brown recluse and related species. The spider is brown, with an average body length of just under ½ in (10 mm). A characteristic dark violin-shaped marking (“fiddleback”) is found on the top of the upper section of the body (Figure 206). The brown recluse spider is found in dark, sheltered areas, such as under porches, in woodpiles, and in crates of fruit. It is most active at night. It commonly bites when it is trapped, but is not otherwise aggressive toward humans.

Figure 206 Brown recluse spider with typical violin-shaped marking on the top side of the cephalothorax.

The bite of the brown recluse spider may cause very little pain at first, or a sharp sting may be felt. The stinging subsides over 6 to 8 hours, and is replaced by aching and itching. Within 1 to 5 hours, a painful red or purplish blister sometimes appears, surrounded by a bull’s-eye of whitish-blue (pale) discoloration, with occasional slight swelling. The red margin may spread into an irregular fried-egg pattern, with gravitational influence, such that the original blister remains near the uppermost part of the lesion. The victim may develop chills, fever, weakness, and a generalized red skin rash. Severe allergic reactions within 30 minutes of the bite occur infrequently. Over 5 to 7 days, the venom causes a violet discoloration and breakdown of the surrounding tissue, leading to an open ulcer that may take months to heal. If the reaction has been severe, the tissue in the center of the wound becomes destroyed, blackens, and dies.

Treatment for a Brown Recluse Spider Bite

Until you receive other advice, treat the wound with a thin layer of mupirocin or bacitracin ointment, or mupirocin cream, underneath daily dressing changes. Do not apply topical steroids. Some persons have touted application of topical nitroglycerin, but there is not yet sufficient scientific evidence to routinely support this therapy.

Other Spiders

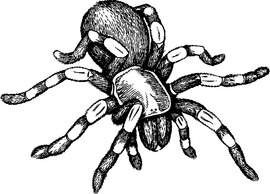

Some tarantulas (Figure 207) carry hairs that can irritate the skin, eyes, and mucous membranes of humans. When the spider is threatened, it rubs its hind legs over its abdomen and flicks thousands of hairs at its foe. These hairs can penetrate human skin and cause swollen bumps, which can itch for weeks. If any hairs or hair fragments remain in the skin, they can removed with repeated applications and peelings of sticky tape. After that, treatment is with an oral antihistamine and topical medication such as StingEze liquid. A topical antihistamine or corticosteroid preparation may provide some relief.

The hobo spider may cause a reaction similar to, but less severe than, a brown recluse spider. The bite wound should be treated accordingly (see page 380).

SCORPIONS

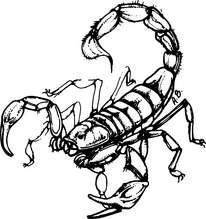

Scorpions are found in deserts and warm tropical climates, hidden under stones, fences, and garbage. In the United States, the most dangerous species is the nocturnal bark scorpion Centruroides exilicauda, which is found almost exclusively in the southwestern states and can be up to 2 in (5 cm) long. This yellowish-brown (straw-colored), solid or striped species is distinguished from other scorpions by its slender body and a small tubercle (telson) at the base of its stinger (Figure 208). The sting is inflicted with the last segment of the tail, and it is immediately exquisitely painful; the pain is made much worse by tapping on the site of the injury. Other symptoms include excitement, increased salivation, sweating, numbness and tingling around the mouth, nausea, double vision, nervousness, muscle twitching and spasms, rapid breathing, shortness of breath, high blood pressure, seizures, paralysis, and collapse. A child under age 2 years is at particular risk for a severe reaction. Stings by nonlethal scorpion species are similar to bee stings.

MOSQUITOES

Female mosquitoes bite humans in quest of a blood meal, to lay eggs. Because they breed in water, they are most frequently found in marshy, wetland, or wooded areas. Although many tend to swarm at dusk, different species feed at different times. The insects are attracted to host odors (long-range), exhaled carbon dioxide (midrange), and heat and moisture (short-range). During a bite, mosquito saliva is injected into the victim. This liquid contains the substances that cause the classic reaction—a small white or red bump that itches, and then disappears. Those who have been sensitized because of previous bites can have delayed (12 to 48 hours) reactions, which include intense swelling and itching. In addition, mosquitoes transmit diseases such as malaria (see page 146) and various types of encephalitis.

Therapy for mosquito bites is limited to cool compresses and skin hygiene to prevent infections. If someone is bitten intensely and suffers a severe delayed allergic reaction, he may benefit from a course of prednisone similar to that used to treat poison oak (see page 234). Oral antihistamines, such as cetirizine hydrochloride, given before mosquito exposure, may lessen the reaction to mosquito bites in highly sensitized persons.

BITING FLIES

Treatment is symptomatic and similar to that applied under step 5 for the local reaction to an insect sting (see page 376).

FLEAS

Treatment is symptomatic and similar to that applied under step 5 for the local reaction to an insect sting (see page 376).

CHIGGERS

Treatment is symptomatic and similar to that applied under step 5 for the local reaction to an insect sting (see page 376). One percent phenol in calamine may be helpful. Home remedies for chigger bites are common, and include application of dabs of clear nail polish or meat tenderizer. None are of proven benefit. If a person is bitten intensely and suffers a severe reaction, he may benefit from a course of prednisone similar to that used to treat poison oak (see page 234), or application of superpotent topical corticosteroid cream or ointment, such as 0.05% clobetasol applied thinly several times daily, but for only a few days’ duration. Prevention is key; pretreatment of clothing with permethrin, similar to the approach taken to repel ticks, is beneficial.

CENTIPEDES AND MILLIPEDES

Centipedes bite their victims with their fangs, not with their feet or rear-end appendages. Scolopendra species bites have been reported to cause burning pain, swelling, redness, and swollen lymph glands. More severe reactions are rare. Treatment is symptomatic and similar to that applied under step 5 for the local reaction to an insect sting (see page 376), with the exception that the application of meat tenderizer has never been suggested to be of benefit for a centipede bite.

Millipedes do not bite their human victims; instead, they eject secretions that can cause skin irritation. In tropical regions, this has been reported to begin with brown skin staining, followed by a burning sensation with blisters. Millipede secretions that enter the eye may cause severe irritation similar to a corneal abrasion (see page 180). There is no specific treatment, other than to irrigate the affected area (particularly the eyes) promptly and thoroughly with disinfected water or saline solution, and then treat as a burn (see page 108) or, if the eye is injured, as a corneal abrasion (see page 180).

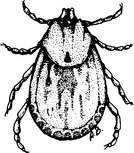

TICKS

Ticks (Figure 209) are ubiquitous in wooded regions and fields, and readily attach to the skin of victims, most commonly on the legs, lower abdomen, genitals, back, and buttocks. They may also attach to the scalp, armpits, groin, and other cozy (for a tick) areas. They like shade and moist skin, and may wander for a while in search of a comfortable spot. Up to 20% of tick attachments are in locations that cannot be visualized by the victim. Once in place, ticks hang on with their mouthparts and feed on the victim’s blood. The tick is the intermediate host for the vectors of many diseases, such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever (see page 155), Colorado tick fever (see page 156), relapsing fever (see page 153), ehrlichiosis (see page 159), babesiosis (see page 159), and Lyme disease (see page 157). In fact, ticks are the most common insect vectors of disease in the United States.

Tick Avoidance

Wear proper clothing to prevent tick attachment. Ticks have a more difficult time attaching to smooth, tightly woven fabrics. Keep shirts tucked into pants and trouser cuffs tucked into socks. Light-colored clothing displays ticks. If clothing is worn loosely fitting, it will not be pulled close to the skin, and it will be more difficult for a tick or insect to bite through and reach the skin. If mesh clothing or a head net is deployed, the mesh size should be less than 0.3 mm. Wear a light-colored, broad-brimmed hat to protect the head and neck. If ticks are seen on clothing, they may be removed by trapping them on a piece of cellophane tape or using a sticky tape lint roller device. Unless a hot cycle in a clothing dryer is employed, washing clothing may not remove tick nymphs. The deer tick, which transmits the infectious agent of Lyme disease, is extremely small, particularly in juvenile stages. The best repellent is permethrin (Permanone) applied to clothing, not to skin (see page 390), but DEET is also effective.

Tick Removal

The proper way to remove a tick is to grasp it close to its mouthparts with tweezers or with the fingernails and pull it straight out with a slow and steady motion (Figure 210). Another excellent way to remove a tick is with a grooved or V-shaped device designed to slide between the tick and the skin to trap the tick and allow it to be pulled from the skin. Do not twist the tick. If you must remove it with your fingers, use tissue paper or cloth to prevent skin contact with infectious tick fluids. Do not touch the tick with a hot object (such as an extinguished match head) or cover it with mineral oil, alcohol, kerosene, camp stove fuel, or Vaseline; these remedies might cause the tick to struggle and regurgitate infectious fluid into the bite site. Viscous lidocaine 2% applied to a tick for 5 minutes will cause it to detach its grip, but it is not known if the tick regurgitates. If a tick head is buried in the skin, you can apply permethrin (Permanone insect repellent), using a cotton swab, to the upper and lower body surfaces of the tick. After 10 to 15 minutes, the tick will relax and you will be able to pull it free. After the tick is removed, carefully inspect the skin for remaining head parts, and gently scrape them away. Wash the bite site with soap and water or with an antiseptic, and also wash your hands.

CATERPILLARS

The puss caterpillar, Megalopyge opercularis (Figure 211), is found in the southern United States. The gypsy moth caterpillar, Lymantria dispar (Figure 212), and the flannel moth caterpillar, M. cirpata, are found in the northeastern United States. The numerous bristles that cover the bodies of these species cause skin irritation when the caterpillar is directly touched, or when there is contact with detached bristles deposited on outdoor bedding or hung clothes. Shortly after exposure, the victim suffers a rash with redness, itching, burning discomfort, and hives. Blisters are rare. If a large area of skin is involved, the victim can become nauseated and weak, and can suffer from high fever. If the small bristle hairs are inhaled, shortness of breath or asthma-like (see page 45) symptoms may follow. If the eyes come into contact with these hairs, symptoms include redness, itching, tearing, and swollen eyelids. Handling particularly venomous species can cause intense pain, headache, fever, vomiting, and swollen lymph glands.

Treatment of the skin consists of applying adhesive tape (duct tape is best) to attempt removal of the bristles, followed by an application of calamine lotion. A good alternative is to apply a commercial facial peel or thin layer of rubber cement, allow it to dry, and then peel it off; the bristles will be carried with it. Management of an allergic reaction similar to that from poison oak is described on page 234. If the redness and swelling are prominent, the victim may be treated with an oral antihistamine, such as fexofenadine (60 mg twice a day) and a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug for 5 days. If the pain is severe, administer a potent pain medicine.

BEETLES

Blister beetles of the Epicauta species (Figure 213) are found throughout the eastern and southern United States. These insects are usually about ½ in (1.3 cm) long and extremely agile. When they make contact with the skin, they release a chemical substance (cantharidin) that is very irritating. Initial contact is painless. Within a few hours, blisters appear, which are not particularly painful unless they are large and broken. If a blister beetle is squashed on the skin, an enormous blister follows.

The treatment is the same as for a second-degree burn (see page 108). If “beetle juice” enters the eye, the eye should be irrigated copiously and the injury managed as you would snowblindness (see page 187). In general, it is a good idea to wash the skin with soap and water after any insect contact.

SUCKING BUGS

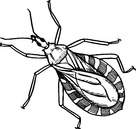

Triatomids (Figure 214) usually bite humans during the night on exposed body parts, and feed for up to 30 minutes. The initial bite is painless, without any immediate reaction. However, the wheel bug, black corsair, or masked bedbug hunter bite may cause pain similar to a hornet sting.

Treatment is symptomatic and similar to that applied under step 5 for the local reaction to an insect sting (see page 376).

SKIN INFESTATION BY FLY LARVAE

The mature larva will attempt to exit the skin through the breathing pore, and is noticed as a small white object “peeking” through the hole. To test to see if a larva is present, place a small amount of the victim’s saliva over the hole—if it bubbles, the larva is likely there and breathing. You can force it to exit through the hole by suffocating it: Cover the breathing pore with bacon or pork fat, a strip of meat, chewing gum, wax, fingernail polish, paraffin, or a plug of grease. Usually, 12 hours of occlusion will cause the larva to exit the hole or die from asphyxiation. Moistened tobacco leaves or nicotine drops will paralyze the larva. It is unwise to make a rough incision to remove the larva, because if the creature is ruptured, it will leak substances into the wound that cause inflammation and promote infection. It is sometimes possible to simply squeeze the lesion and force extrusion of the larva, but care must be taken not to rupture the larva. If nothing is done to force the larva to leave the skin, it will do so on its own in a few weeks, but this is generally not recommended because of the pain and potential for abscess (see page 241) formation.

INSECT REPELLENTS

Chemical insect repellents are mandatory whenever you travel through mosquito, sand fly, or tick territory. Different repellents work by different mechanisms and therefore their effectiveness varies for different types of insects, but I can make some general recommendations that will be applicable in most situations.

To be effective, a repellent should be applied to the skin (liquid) and clothing (spray). After you swim, bathe, or perspire excessively, reapply it. If you are being bitten by insects, reapply the repellent. In windy conditions, repellents evaporate quickly and may need to be reapplied. Children under 2 years of age should not have insect repellent applied to the skin more than once in 24 hours (it is more effective to apply it to the clothing, anyhow). If you—re applying both a sunscreen and an insect repellent, apply the sunscreen first, so that it can be absorbed; wait 30 minutes, and then apply the insect repellent. There are also sunscreen–insect repellent combinations, such as Coppertone Bug & Sun. Bug Guard contains Skin-So-Soft (mostly mineral oil) in combination with citronella, enhanced by a sunscreen.

The following recommendations are offered to avoid toxicity:

1. Apply repellent sparingly, and only to exposed skin or clothing. Keep it out of the eyes. Do not apply repellent underneath clothing.

2. Avoid high-concentration products on the skin, particularly with children.

3. Do not apply repellent to cuts, wounds, or irritated skin. Apply to face by dispensing into the palms of your hands, and then using these to apply a thin layer to the face. Afterward, wash your hands.

4. Do not inhale or ingest repellents. Do not spray aerosol or pump products directly on your face. Spray your hands and then use them to rub the repellent on the face, avoiding the eyes and mouth. Do not spray around food.

5. Use long-sleeved clothing and apply repellent to fabric rather than to skin.

6. Don’t use repellent on children’s hands, which may be rubbed in the eyes or placed in the mouth.

7. Repellent applied to a wristband is not sufficient protection—you must apply the repellent directly to all the skin areas to be protected.

8. Do not reapply repellent in normal weather conditions (unless it is a non-DEET repellent).

9. Wash repellent off the skin after the insect bite risk has ended.

Permethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid based on the naturally occurring pyrethroids that are extracted from the East African pyrethrum flower (a chrysanthemum), is actually an insecticide; that is, permethrin-containing products kill insects and ticks. Because permethrin carries some potential toxicity to humans it should be used only on clothing (or on shoes, certain camping gear, bed nets, etc.), not on skin. For instance, permethrin is known to cause eye irritation if the chemical comes in contact with a person’s eyes. Although permethrin in a 5% lotion or cream is sometimes prescribed by physicians for application to skin for treatment of mite (e.g., scabies) infestation, these medical dermatologic preparations are not recommended for use as insect repellents. In the past, combination DEET-permethrin (the latter in very low concentration) soaps have been field tested for use as an insect repellent. While they have been acceptable to the persons who used them, a commercial product based on this concept has not yet come to market.

If you decide to apply permethrin spray to clothing, be certain to do the following:

1. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions closely. Do not exceed recommended spraying times.

2. Treat clothing only. Do not apply to skin.

3. Apply the permethrin in a well-ventilated outdoor area, protected from the wind.

4. Only spray the permethrin on the outer surface of clothing and shoes.

5. In a concentration of 0.5%, it can be sprayed on both sides of clothing to lightly moisten the outer surface of the clothing item; it is not necessary to have the clothing soaked through (saturated).

6. Be certain to apply completely over socks, trouser cuffs, and shirt cuffs, where insects may attempt to crawl or fly through openings to your skin.

7. Hang treated clothing outdoors and allow to dry for at least 2 to 4 hours in nonhumid conditions and for at least 4 hours in humid conditions.

8. Treat clothing no more often than every 2 weeks.

9. Launder treated clothing separately from other clothing at least once before retreating.

10. Assume that your treated clothing is effective for repellency for 2 weeks or more. Wear it only when you need to repel insects and arthropods. Store it in a separate impermeable (to permethrin) bag when not in use.

Permethrin (Permanone tick repellent; Duranon tick repellent) may be applied to clothing, netting, and footwear. A single application is usually good for 1 to 2 weeks, or 20 washings. To apply permethrin to clothing or netting, add 2 ounces of permethrin to a quart of water in a plastic bag. The solution will turn milky white. Put the garment or netting in the bag, seal the bag, and let the item soak for 10 minutes. After the soak, allow the clothing or netting to effectively dry (in the sun or hung) for a few hours. Permethrin is effective against ticks and mosquitoes.

LEECHES

To remove a leech, don’t pull it off—the residual sore may be larger. Instead, apply lemon juice, salt, vinegar, tobacco juice, or insect repellent. Using a lighted or recently extinguished match or glowing ember may cause a skin burn. If the detached leech sticks to your fingers, roll it between them. If a leech is attached to someone’s eye, shine a flashlight close to it; it may move toward the light and away from the eye. The medical considerations for a leech bite are itching and secondary infection. Insect repellents (see page 390), particularly DEET applied to clothing and skin, will discourage leech attachment. Slippery grease (such as petroleum jelly) applied to exposed skin may also help. Wear waterproof boots when wading in leech-infested water, and tuck in pant legs.