Chapter 140 Insect Allergy

Etiology

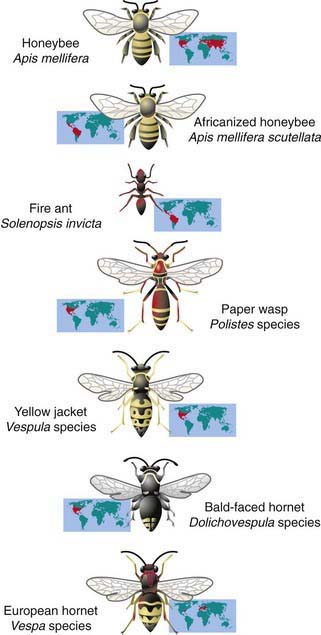

Most reactions to biting and stinging insects, such as those induced by mosquitoes, flies, and fleas, are limited to a primary lesion isolated to the area of the bite and do not represent an allergic response. Occasionally, insect bites or stings induce pronounced localized reactions or systemic reactions that may be based on immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions. Systemic allergic responses to insects are attributed most typically to immunoglobulin (Ig) E antibody–mediated responses, which are caused primarily by stings from venomous insects of the order Hymenoptera and more rarely from ticks, spiders, scorpions, and Triatoma (kissing bug). Members of the order Hymenoptera include apids (honeybee, bumblebee), vespids (yellow jacket, wasp, hornet), and formicids (fire and harvester ants) (Fig. 140-1). Among winged stinging insects, yellow jackets are the most notorious for stinging because they are aggressive and ground dwelling, and they linger near activities involving food. Hornets nest in trees, whereas wasps build honeycomb nests in dark areas such as under porches; both are aggressive if disturbed. Honeybees are less aggressive, nest in tree hollows, and, unlike the stings of other flying Hymenoptera, honeybee stings almost always leave a barbed stinger with venom sac.

Treatment

Anaphylactic reactions after a Hymenoptera sting are treated exactly like anaphylaxis from any cause. Therapies may include oxygen, epinephrine, intravenous saline, steroids, antihistamines, and other treatments (Chapter 143). Referral to an allergist-immunologist should be considered for patients who have experienced a generalized cutaneous or systemic reaction to an insect sting, need education about avoidance and emergency treatment, may be candidates for VIT, or have a condition that may complicate management of anaphylaxis (use of β-blockers).

Venom Immunotherapy

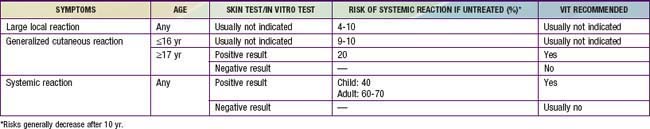

Hymenoptera VIT is highly effective (95-97%) in decreasing the risk for severe anaphylaxis. The selection of patients for VIT depends on several factors (Table 140-1). Individuals with local reactions regardless of age are not at increased risk for severe systemic reactions on a subsequent sting and are not candidates for VIT. The risk of a systemic reaction for those who experienced a large local reaction is no more than 4-10%; testing or VIT is usually not recommended, and prescription of self-injectable epinephrine is considered optional but usually not necessary. Those who experience severe systemic reactions, with airway involvement or hypotension, and have a positive skin test result should receive immunotherapy. Immunotherapy against winged Hymenoptera is not usually indicated for children ≤16 yr of age in whom stings have caused only generalized urticaria or angioedema, because their risk for a reaction after a subsequent sting is <10%, with isolated skin reactions the most likely event. The risk could be reduced to 1% after treatment with VIT, so it is an option to consider if multiple future stings are anticipated. Immunotherapy against Hymenoptera is indicated in those ≥17 yr of age if venom skin test results are positive and there is a history of generalized urticaria or a systemic reaction, because their risk for future systemic reactions is ≈60-70%. VIT is usually not indicated if there is no evidence of IgE to venom. The incidence of adverse effects in the course of treatment is not trivial in adults, as 50% experience large local reactions and about 7% experience systemic reactions. The incidence of both local and systemic reactions is much lower in children. It is uncertain how long immunotherapy with Hymenoptera venom should continue; lifelong treatment has been advocated for patients with very severe reactions. Consideration to discontinue therapy after 3-5 yr has been suggested, however, because >80% of adults who have received 5 yr of therapy tolerate challenge stings without systemic reactions for 5-10 yr after completion of treatment. Long-term responses to treatment are even better for children. Follow-up over a mean of 18 yr of children with moderate to severe insect sting reactions who received VIT for a mean treatment period of 3.5 yr and were stung again showed a reaction rate of only 5%; untreated children experienced a reaction rate of 32%. Whereas duration of therapy with VIT may be individualized, it is clear that a significant number of untreated children retain their allergy.

Freeman TM. Hypersensitivity to hymenoptera stings. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1978-1984.

Golden DB. Insect allergy in children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:289-293.

Golden DB, Kagey-Sobotka A, Norman PS, et al. Outcomes of allergy to insect stings in children, with and without venom immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:668-674.

Moffitt JE, Golden DB, Reisman RE, et al. Stinging insect hypersensitivity: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:869-886.

Müller U, Golden DB, Lockey RF. Immunotherapy for hymenoptera venom hypersensitivity. Clin Allergy Immunol. 2008;21:377-392.

Tankersley MS. The stinging impact of the imported fire ant. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:354-359.