1 Inpatient medical care

Good medical practice

Providing good clinical care

The General Medical Council in the UK has published guidance for doctors and outlines their duties of care (www.gmc-uk.org). National practices differ from country to country but all have similar regulatory bodies and guidance. Remember:

Clinical records

Records should be written with a pen and be dated and signed, with a printed name below the signature. They must be legible, clear and accurate. They must include clinical findings, investigations and treatment(s) prescribed, the consent given, the decisions made and the information given to the patient, with details of follow-up or referrals. Records should be updated at the time of seeing the patient or soon after. The original record should never be altered but an additional note (signed and dated) should be made alongside any mistake. Records should be kept in a secure place. Computerized records are increasingly being used in some countries.

Assessment and general management

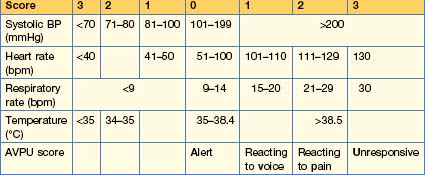

Modifed Early Warning Score (MEWS)

This simple physiological scoring system (Table 1.1) can be used at the bedside in a medical admission unit. It identifies patients at risk of deterioration who will require a higher level of care in either an HDU or an ICU.

SBAR

This is a mechanism by which teams can clarify what information should be communicated between members of the team. It develops better communication and teamwork, leading to increased patient safety. Standardized prompt questions in the four sections listed below are used to ensure that members of staff share concise and focused information with the correct level of detail. SBAR aids good communication and encourages prompt action on the part of the receiver.

• S Situation

Pre- and peri-operative care and assessment

History and examination

Co-morbidities

Routine pre-operative tests

These are often not necessary in a patient undergoing minor or elective surgery.

Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis

Anti-DVT/VTE measures include early ambulation, which reduces the risk of DVT/PE. Graduated compression stockings (unless patient has peripheral arterial disease) and low-molecular-weight heparin or oral anti-thrombotic agents e.g. dabigatran or rivaroxaban should be used. See p. 245 for details.

Specific interviews

Breaking bad news

These interviews are often difficult. The aim is to make sure that the patient is enabled to understand and make the best of even very bad circumstances. These interviews should always be carried out in a quiet place and without interruption; if possible, patients should have someone with them. Explain your status and your responsibility to them.

Patient safety and infection control

Prescribing

The WHO Guide to Good Prescribing is a useful training programme to assist in prescribing medicines (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1994/WHO_DAP_94.11.pdf).

Drug metabolism

Pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) and pharmacodynamics (what the drug does to the body)

Many drugs are metabolized by the liver. The metabolism varies between individuals, often because of changes in the cytochrome p450 family of enzymes. Inhibition or induction of cytochrome p450 isoenzymes is a major cause of drug interaction. Some examples are given in Box 1.1. Thus, for example, warfarin is metabolized by CYP2C9. Between 2 and 10% of people are homozygous for an allele that results in low enzyme activity and this leads to higher plasma warfarin levels.

The variability of a drug’s action within the body is partly due to the drug receptor and the polymorphism of this receptor.

Prescribing for the elderly

| Drug | Effect |

|---|---|

| β-Blockers (including eye drops) Digoxin |

Bradycardia |

| Nitrates α-Adrenoceptor-blockers Diuretics |

Postural hypotension |

| Diuretics (thiazides) | Glucose intolerance, gout |

| Antimuscarinic drugs Tricyclic antidepressants Neuroleptics Minor tranquillizers Anticonvulsants Hypnotics Opioids |

Confusion, cognitive dysfunction |

| Bisphosphonates (mainly alendronic acid) | Oesophageal ulceration and stricture formation |

| NSAIDs | Gastric erosions Upper gastrointestinal bleeding Perforated peptic ulcer Renal impairment |

Prescribing in pregnancy/breast feeding

Never prescribe a drug to pregnant women unless it is absolutely necessary and you have checked for possible teratogenic effects on the fetus. Appendix A gives websites for drug use. If a known teratogenic drug is required during pregnancy (e.g. an anticonvulsant), always discuss the adverse effects on the fetus with the parents, preferably prior to conception.

Writing a prescription

Prescribing controlled drugs

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs)

Classification

Two types of ADR are recognized (Table 1.3):

| Drug | Adverse reaction |

|---|---|

| Type A (augmented) | |

| Anticoagulants | Bleeding |

| Insulin | Hypoglycaemia |

| ACE inhibitors/antagonists | Hypotension |

| Antipsychotics | Acute dystonia and dyskinesia Parkinson’s disease Tardive dyskinesia |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Dry mouth |

| Amiodarone | Hyperthyroidism Hypothyroidism Pulmonary fibrosis |

| Cytotoxic agents | Bone marrow dyscrasias Cancer |

| Glucocorticoids | Osteoporosis |

| Type B (idiosyncratic) | |

| Benzylpenicillin | Anaphylaxis |

| Radiological contrast media | Anaphylaxis Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, e.g. gadolinium |

| Amoxicillin | Maculopapular rash |

| Sulphonamides Lamotrigine |

Toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| Volatile anaesthetics Suxamethonium |

Malignant hyperthermia |

| Diclofenac Isoflurane, sevoflurane Isoniazid Rifampicin Phenytoin |

Hepatotoxicity |

Clinical trials

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Odds/risk ratios and number needed to treat

If, for example, the total was 4, it would mean there was 4 times the risk.

Interpretation of diagnostic tests

A high LR indicates that a particular disorder is more likely in people with a given result.

Statistical analysis

The average

The ‘average’ value (or ‘central tendency’) can be expressed as follows:

In a symmetrically distributed population the mean, median and mode are the same.

‘p’ value

An alternative to the CI is the probability (p value), which is used if the population has a normal distribution. The basic assumption is that there is no difference between two groups (i.e. the Null Hypothesis). Statistical tests are used to determine the probability that an observed difference is due to chance. By convention, if it is less than 1 in 20 (p < 0.05), it is described as being ‘statistically significant’ and is unlikely to be due to chance (i.e. rejecting the Null Hypothesis). If the p value is >0.05, there is no statistical difference between the two groups and the Null Hypothesis cannot be rejected.

Standard deviation (SD) v standard error (SE)

The SE of the sample mean depends on both the SD and also the sample size, i.e.

The SE will fall as the sample size is increased, but the SD will not change.

Correlation

Do not attempt resuscitate (DNAR) orders

Care of the dying

A decision by a multidisciplinary that a patient is dying is agreed and should be recorded in the clinical record. This decision must be discussed with the carers and relatives of the patient. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2004) guidance on improving supportive and palliative care for adults is shown in Box 1.2.

Box 1.2

Source: National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2004 Guidance on Cancer Services. Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer.

Best practice in the last hours and days of life

Confirmation of death

Verification of death can be daunting. Ask relatives to leave the ward while you confirm the death.

Findings should be clearly documented in the medical notes, with the exact time of pronouncement of death. The presence or absence of a pacemaker and radioactive implant should be noted, as this may cause explosions if the body is cremated. The presence of other medical devices, such as cannulae, should be documented; these should not be removed. A death certificate should be filled out as soon as practicable.

Specific clinical problems

Allergy

Clinical features of allergic reactions

Investigations

Treatment

Anaphylaxis

This life-threatening emergency is due to a systemic allergic reaction, which is rapid in onset. This reaction requires ‘priming’ by an antigen followed by re-exposure and the allergen must be systemically absorbed (ingestion or parenteral injection). Serum platelet-activating factor (PAF) levels have been found to correlate directly with the severity of anaphylaxis, whereas PAF acetylhydrolase (the enzyme that inactivates PAF) correlates inversely.

Causes

Clinical features

The clinical features are shown in Box 1.3. Symptoms range from widespread urticaria and angio-oedema (laryngeal oedema, airway obstruction) to cardiovascular collapse, respiratory arrest and death. Initially there may only be tingling, warmth and itchiness. This is followed by a generalized flush, hypotension, bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema and cardiac arrhythmias; myocardial infarction can follow. Death can occur within minutes.

Anxiety

Anxiety is common in the sick and hospitalized patient. Discussion of the cause of the anxiety with the patient, along with reassurance, is often sufficient to relieve the anxiety. Hyperventilation, which is a feature of anxiety, is described in Box 1.4

Benzodiazepines

These are used for the short-term relief of severe anxiety; their action is described on p. 22. Agents used are:

The dose should be as small as possible to control symptoms.

Management of the severely disturbed patient

Severely disturbed patients (see also p. 626) are usually seen in the accident and emergency department. The primary aims of management are the control of dangerous behaviour and establishment of a provisional diagnosis. The main causes are personality disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, and psychosis. For delirium tremens, see p. 627; hallucinations are desccribed in Box 1.5.

Box 1.5 Hallucination

A hallucination is defined as a perception in the absence of a stimulus. It is:

Three specific strategies are employed when dealing with the violent patient:

This procedure must be carefully documented and be within legal boundaries.

Falls

Insomnia

Benzodiazepines

The red eye

Box 1.6 gives the red flags for a red eye. URGENT REFERRAL TO EYE CLINIC IS MANDATORY.

Conjunctivitis

Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG)

Anterior uveitis (iritis)

• Treatment

Pain management

Pain in palliative care is discussed on p. 292.

Analgesics, e.g. NSAIDs as used in rheumatic disorders, are discussed on p. 298. They (e.g. diclofenac 150 mg orally, IV, IM or rectally in 2–3 divided doses daily) are also useful in ureteric colic if renal function is normal and in post-operative musculoskeletal pain, for example.

Simple and compound analgesic agents

Severe pain

If simple analgesia or NSAIDs are ineffective, opioid analgesics are used.

Pressure ulcers (decubitus ulcers, bedsores)

Normal individuals feel the pain of continued pressure, and even during sleep, movement takes place to change position continually. However, ulcers can occur in the elderly and in immobile, unconscious or paralysed patients. They are due to skin ischaemia from sustained pressure over a bony prominence, usually the heel and sacrum. They can develop within 1–2 hours, particularly in patients on hard emergency room trolleys; 70% occur within 2 weeks of hospitalization. Once they develop, they are difficult to heal and are associated with an increased mortality. Pressure sores may be graded: