Chapter 14. Injuries to the lower limb

Fractures at the upper end of the femur: general considerations

Fractures at the upper end of the femur are seen in young patients and high energy injuries or in elderly patients with bones weakened by osteoporosis. Because they live longer than men and the hormonal changes of the menopause make them more subject to osteoporosis, these fractures are commoner in women. The fractures are becoming more and more frequent as the average age of the population increases and in many areas they are the commonest fractures admitted to hospital.

Fractures at the upper end of the femur create clinical, social and economic problems.

Clinical problems

Because the fractures occur in elderly patients, medical problems are seen that are not encountered in fit young adults with broken bones or in older patients undergoing reconstructive surgery. Assessment therefore requires special attention to the general medical condition, drugs that the patient is taking and the social history.

Bronchopneumonia and cerebral confusion are particular problems and the prognosis for an elderly patient with a fracture at the upper end of the femur is poor.

Approximately 10% of patients die within 6 weeks of this injury and 30% within 1 year.

Of the remaining 70% who survive, one-third are unable to return to their former level of independence or physical activity as the result of the fracture.

Social problems

The fractures are important from the social stand-point because they often connote the end of independent existence, particularly if the patient has unsuitable accommodation and was unfit to live alone even before the fracture. Admission to hospital – a strange and frightening place for an elderly patient at the best of times – always causes anxiety which, when coupled with the upset of operation, may be so great that the patient is quite unable to cope with the problems of rehabilitation.

If return home is impossible and alternative accommodation has to be found, close liaison with the social services, family practitioner and health visitor is mandatory (p. 88). The mental adjustment asked of the patient will be even greater and this must be taken into consideration.

Economic problems

These fractures consume a large part of health service resources in terms of beds, nurses and support outside hospital. As the fractures become more common, pressure on resources becomes greater but there is seldom any increase in the provision of services to match the increased demand.

The result is more pressure on less urgent services, which in practice means that patients with non-urgent conditions cannot be treated and must wait longer for admission to hospital. The level of provision for fractured necks of femur is largely responsible for long orthopaedic waiting lists.

Fractures of the femoral neck

Fractures of the acetabulum are dealt with on page 000.

Clinical features

Fractures of the femoral neck occur after a trivial injury or even without any injury at all; the bone may be so brittle that it snaps as the patient gets out of a chair.

On examination, the affected leg will be short and externally rotated because the fracture allows the shaft of the femur to move independently of the hip joint, which means that the iliopsoas and gravity will rotate the femur externally instead of rotating the hip internally (Fig. 14.1).

|

| Fig. 14.1

Position of the leg with shortening and external rotation, seen with a displaced fracture at the upper end of the femur.

|

Types of fracture

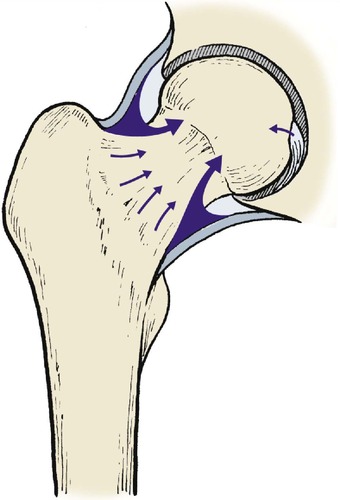

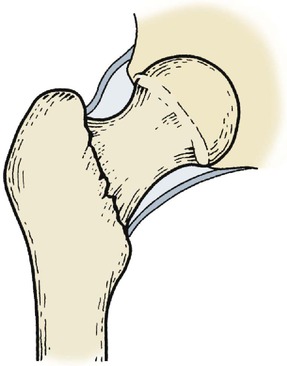

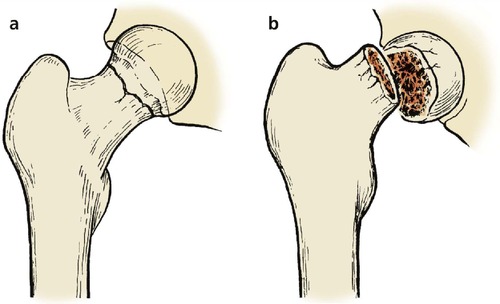

Intracapsular fractures result from a high transcervical fracture and interrupt the blood supply to the femoral head. This is derived from three sources (Fig. 14.2).

|

| Fig. 14.2

Blood supply of the femoral head via the capsule, intramedullary vessels and ligamentum teres.

|

Blood supply to the femoral head

1. Synovium and joint capsule.

2. The medullary cavity.

3. A tiny proportion from the ligamentum teres.

An intracapsular fracture can cut off the blood supply to the femoral head completely, leading to aseptic necrosis, non-union, or both. Because the fracture line is inside the capsule, blood is contained within it. This raises the intracapsular pressure and damages the femoral head still further. It also prevents visible bruising because blood cannot reach the subcutaneous tissues.

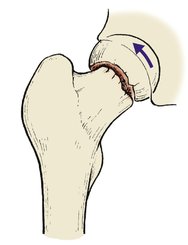

To add to these problems, an intracapsular fracture leaves the femoral head very mobile inside the capsule (Fig. 14.3 and Fig. 14.4), particularly if the fracture is just below the head (subcapital). This makes accurate reduction almost impossible. The posterior cortex may also be crushed.

|

| Fig. 14.3

Displaced subcapital fracture of the femoral neck. The femoral shaft has moved proximally.

|

|

| Fig. 14.4

Displaced transcervical fracture of the femoral neck. The femoral head maintains its correct relationship to the pelvis but the femur is rotated.

|

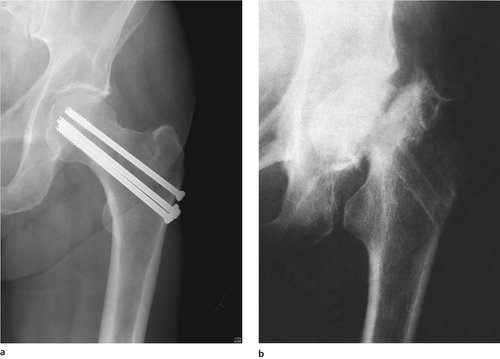

All these factors predispose to non-union and aseptic necrosis (Fig. 14.5), and intracapsular fractures are notorious for their high complication rate.

|

| Fig. 14.5

(a) Internal fixation of a femoral neck fracture with screws. (b) Non-union of a femoral neck fracture with aseptic necrosis of the femoral head. Note how the head has become smaller and denser.

|

Extracapsular and basal fractures are less difficult for three reasons (Fig. 14.6):

1. The blood supply is not interrupted so seriously.

2. The surface area of the fracture available for union is larger and consists of good cancellous bone.

3. The femoral head is less mobile.

|

| Fig. 14.6

Basal fracture of the femoral neck.

|

Nevertheless, non-union and avascular necrosis can occur, and extracapsular fractures must be treated with great respect.

Undisplaced and impacted fractures of the femoral neck present other problems (Fig. 14.7, Fig. 14.8 and Fig. 14.9). Because the bones are jammed tightly together the fracture appears stable and the patient may even be able to bear weight on the leg (Fig. 14.10). Many impacted fractures probably pass undiagnosed and do very well without medical attention, but in some patients the fracture becomes displaced days or even weeks after the injury. An impacted fracture must therefore be carefully observed to be certain that it remains stable, and should be protected until the bones are united.

|

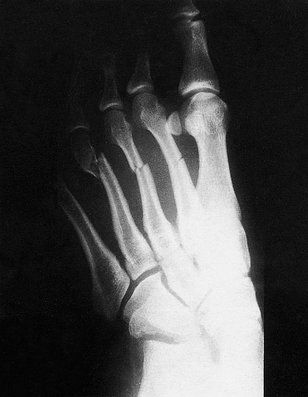

| Fig. 14.7

Impacted fracture of the femoral neck with the head in valgus.

|

|

| Fig. 14.8

Impacted fracture of the femoral neck. The head rolls into valgus and there is double density of the bone at the site of impaction.

|

|

| Fig. 14.9

(a) Undisplaced fracture of the femoral neck; (b) displaced fracture of the femoral neck.

|

|

| Fig. 14.10

Impacted fracture of the femoral head with little valgus deformity. The patient had walked on this fracture.

|

Treatment (intracapsular)

The choice of treatment for femoral neck fractures depends upon three factors:

1. The age and fitness of the patient.

2. The type of fracture.

3. The degree of displacement.

Displaced fractures can be treated by internal fixation or prosthetic replacement.

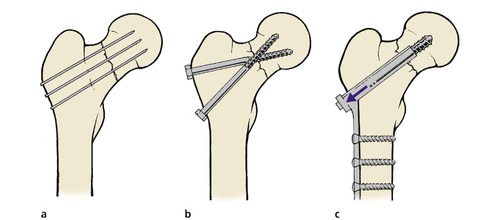

Internal fixation. The fracture can be held with several fine pins, a pair of crossed nails, cannulated screws or a dynamic compression screw and plate. All of these are inserted under image intensifier control (Fig. 14.11).

|

| Fig. 14.11

Methods of internal fixation of femoral neck fractures: (a) multiple pins; (b) crossed screw-nails; (c) compression with dynamic screw and plate.

|

The fracture must be protected from full weight-bearing after fixation, which is difficult in the elderly patient, who may not be able to use crutches easily.

If successful, internal fixation of the fracture produces an almost perfect hip, but if the fracture is complicated by aseptic necrosis or non-union, a second operation will be required to replace the head with a prosthesis (Table 14.1). The femoral head may also collapse onto the pins, damaging the acetabulum.

| Indications |

| Internal fixation: fit; young, little displacement |

| Prosthesis: unfit, old, displaced fractures |

| Results |

| Internal fixation: better long-term result. More complications. May need second operation. Slow rehabilitation |

| Prosthesis: early mobilization. Long-term complications are rarer but more serious. A good guideline is to fix the fractures of fit patients under 65 and replace the rest |

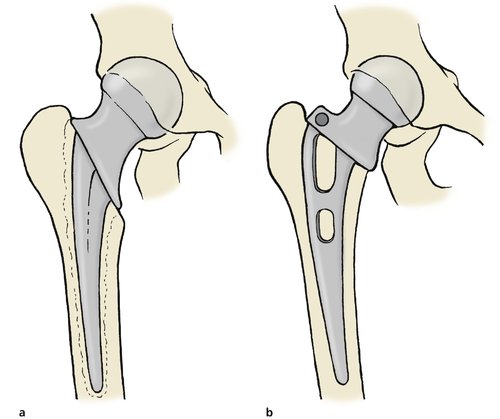

Prosthetic replacement. Immediate replacement of the head with a hemiarthroplasty (e.g. Thompson or Austin Moore prosthesis; Fig. 14.12) avoids the complications of non-union and aseptic necrosis and allows immediate full weight-bearing (Fig. 14.13).

|

| Fig. 14.12

Hip prosthesis for fracture of the femoral neck: (a) Thompson prosthesis secured with cement; (b) Austin Moore prosthesis with no cement.

|

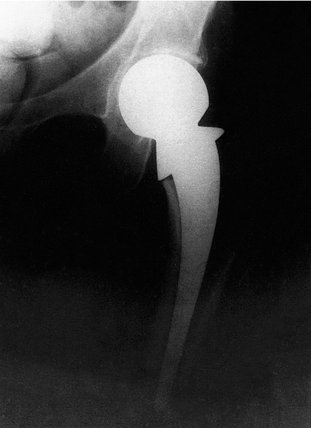

|

| Fig. 14.13

A Thompson prosthesis in position.

|

Early mobilization has many advantages, but the prosthesis may loosen or the femoral head may erode the floor of the acetabulum. If either complication occurs, a total hip replacement will be needed. The wound may also become infected, making excision arthroplasty necessary.

As always with prosthetic replacement, the results are better than other techniques when they are successful but far worse when they are not.

Bipolar prostheses. ‘Bipolar prostheses’ are useful in younger patients. A bipolar prosthesis includes a ball and socket bearing within the space occupied by the femoral head. Thus, the outside diameter of the prosthesis replaces the femoral head and fills the acetabulum. Within this sphere there is a second bearing, usually about 22 mm in diameter. Ball and socket movement can therefore occur at two joints, the interface between the acetabulum and the outer circumference of the prosthesis and the smaller bearing within.

These prostheses are more expensive than simple femoral prostheses but they reduce the forces imposed on the interface between the outer circumference and the acetabulum. They are particularly suitable for younger patients with femoral neck fractures not suitable for internal fixation.

Trochanteric fractures

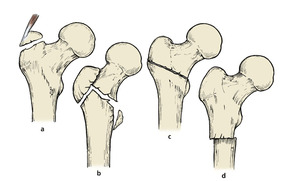

There are four types of trochanteric fracture (Fig. 14.14):

1. Pertrochanteric – through both trochanters.

2. Intertrochanteric – between the trochanters.

3. Subtrochanteric – below the trochanters.

4. Avulsion of the trochanters.

|

| Fig. 14.14

Types of trochanteric fracture: (a) avulsion of the greater tuberosity; (b) pertrochanteric fracture; (c) intertrochanteric fracture between the trochanters; (d) subtrochanteric fracture.

|

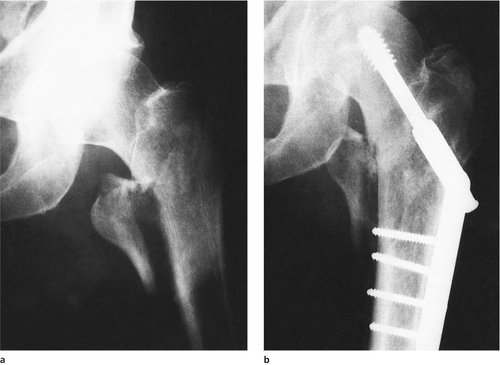

Pertrochanteric and intertrochanteric fractures

Clinical features

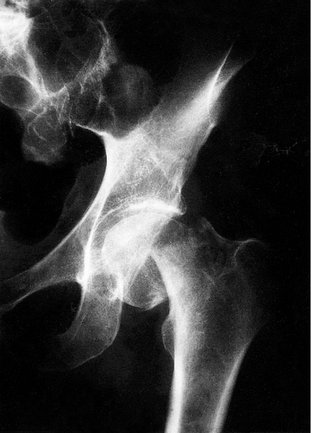

In contrast to fractures through the femoral neck, which occur with little or no trauma, these fractures are caused by a sharp twisting injury, and a history of trauma is usual (Fig 14.15). A further point of difference is that fractures of the femoral neck do not occur in joints affected by osteoarthritis because osteoarthritic bone is denser than normal and the femoral neck is not the weakest point.

|

| Fig. 14.15

Pertrochanteric fracture of the femur following a fall.

|

Fractures through or between the trochanters present different problems from those of the femoral neck. Because the fractures occur through cancellous bone and are surrounded by muscle, they almost always unite but are very unstable and malunion is almost inevitable unless they are fixed internally.

Treatment

Pertrochanteric or intertrochanteric fractures must be held in good position, preferably with a dynamic hip screw or intramedullary hip screw, until united (Fig. 14.16). These implants are not strong enough to take over the mechanical functions of the femur and allow the patient to put all his or her weight through the limb, but they will hold the bones together for the 8 weeks or so needed for union to occur.

|

| Fig. 14.16

(a), (b) Pertrochanteric fracture fixed with compression screw and nail-plate.

|

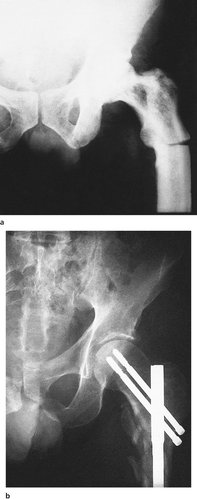

Subtrochanteric fractures

Subtrochanteric fractures are rarer than fractures of the neck or pertrochanteric fractures and are often pathological, occurring through areas of Paget’s disease or metastases (Fig. 14.17a).

|

| Fig. 14.17

(a) Subtrochanteric fracture through an area of Paget’s disease. (b) Subtrochanteric fracture with intramedullary nail.

|

Treatment

Subtrochanteric fractures usually require internal fixation using a nail-plate with a long femoral plate or an intramedullary implant (Fig. 14.17b). If the fracture is pathological, the underlying disorder will also need attention.

Avulsion of the greater trochanter

The greater trochanter can be avulsed by a violent adduction strain.

Clinical presentation

The patient experiences severe pain over the trochanter, abduction is painful and the Trendelenburg sign (p. 25) is positive because the abductor muscles are separated from their bony attachment.

Treatment

Large fragments with much displacement should be reattached if the patient is fit enough but many patients achieve a good result without internal fixation. Non-union is common and causes marked weakness of the abductors, with a Trendelenburg gait.

Fractures at the upper end of the femur in children

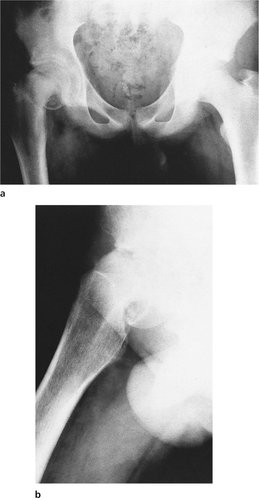

Slipped upper femoral epiphysis

In children, the anatomical equivalent of an intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck is a slipped upper femoral epiphysis (Fig. 14.18). The condition occurs most often during the adolescent growth spurt, is commoner in boys than girls, and consists of a medial and backward displacement of the epiphysis, which rolls the limb into external rotation. The slip is either as a result of a Salter I fracture due to trauma or as an insidious gradual event. The slip is probably the result of weakening of the epiphyseal plate and soft tissues by the hormones of adolescence and this may explain why plump gynaecoid boys are most often affected.

|

| Fig. 14.18

Slipped upper femoral epiphysis: (a) anteroposterior view; (b) lateral view.

|

Clinical features

A slipped upper femoral epiphysis often causes referred pain to the knee and the diagnosis should be suspected in any adolescent with aching around the knee but no abnormality at the knee on clinical examination.

On examination, the appearance is very like that of a femoral neck fracture, the leg lying shortened and externally rotated. The condition is bilateral in 40% of cases and the opposite hip should therefore be checked.

Complications

A slipped upper femoral epiphysis can be followed by avascular necrosis of the epiphysis and early osteoarthritis, or by necrosis of the articular cartilage, which also leads to a stiff and painful hip.

Treatment

Slight or moderate displacement should be treated by fixation with pins to prevent further slip.

Manipulation or traction, however gentle, may cause aseptic necrosis of the epiphysis and should not be attempted. Do not manipulate a slipped upper femoral epiphysis. Although this was once standard practice it is now thought to cause further damage to the epiphysis and its blood supply.

Gross displacement may be irreducible, particularly if there is a long history. In these patients it may be better to accept the deformity and correct it by osteotomy when growth is complete, although there is a high incidence of aseptic necrosis of the head.

Femoral neck fractures

Fractures at the upper end of the femur are essentially an injury of the elderly but they are seen very occasionally in children, when they behave very differently. The fractures are usually basal and the prognosis is worse than in adults.

Although rare, these fractures are serious when they occur and the entire femoral head and neck may undergo aseptic necrosis.

Treatment

Treatment is by careful reduction and internal fixation.

Fractures of the femoral shaft

The femoral shaft can be fractured by direct trauma, twisting or a blow to the front of the flexed knee in a road traffic accident. This injury can also produce a fracture of the patella, ruptured posterior cruciate ligament and posterior dislocation of the hip.

Clinical features

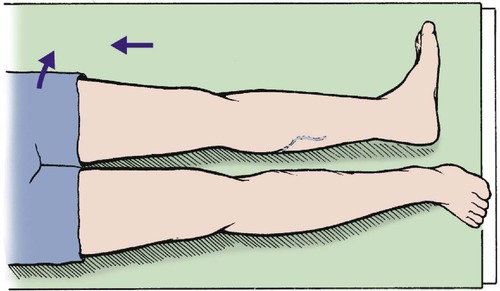

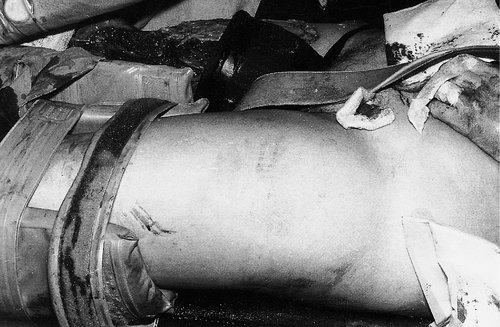

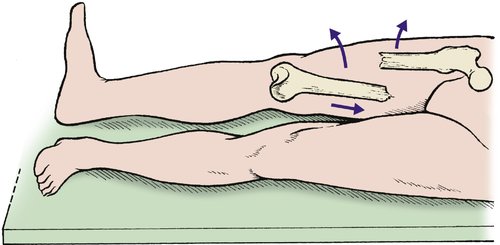

A broken thigh is shorter and fatter than normal and lies with the distal fragment in external rotation and adduction for four reasons (Fig. 14.19):

1. Without the longitudinal stability of the femur, the muscles attached to the upper and lower ends contract and the thigh shortens, which makes it look swollen (Fig. 14.20).

|

| Fig. 14.20

Swelling of the thigh in a patient with a fracture of the femur. An inflatable air splint has been applied for a fracture of the tibial shaft.

|

|

| Fig. 14.19

Position of the fragments after a fracture of the femoral shaft. The upper fragment swings upwards and outwards, the distal fragment is adducted and the foot is externally rotated.

|

2. The adductors are attached to the distal fragment and the abductors to the upper fragment. The fracture separates the two groups, which then act unopposed (p. 39).

3. The weight of the foot rolls the distal fragment into external rotation.

4. The femur is surrounded by muscle which is lacerated by the sharp ends of the fractured bone and the thigh fills with blood. The bone also bleeds.

Complications

• Haemorrhage, which can lead to cardiovascular collapse. This can be corrected by adequate transfusion.

• Infection, particularly if a wound is contaminated and wound debridement has been inadequate.

• Non-union, which is common in midshaft fractures, high speed trauma and fractures with soft tissues interposed between the fragments. Non-united fractures need bone grafting and internal fixation.

• Malunion, caused by abductors and adductors acting unopposed on the proximal and distal fragments, respectively. A varus deformity results from this combination of forces.

• Arterial and nerve injury is uncommon but does occur. The neurological and vascular state of the foot should always be checked and recorded.

Treatment

Immediate care

The blood loss from a fractured femur, whether open or closed, is between 2 and 4 units (1–2 litres). An intravenous line should therefore be set up and blood sent to the laboratory for haemoglobin estimation and cross-matching. If there are no other fractures, it may be possible to avoid transfusion, but if any other injuries are present, 2 units of blood should be given as soon as it is available.

Open fractures are usually open from within out, with a wound on the lateral side or the front of the thigh. The wound should be debrided meticulously in the operating theatre and all foreign material removed. It is usually wise to pack the wound and treat it by delayed primary suture (p. 139). Only in very exceptional circumstances can a wound be made clean enough to close immediately. Antibiotics and antitetanus treatment should be given, as for any open fracture.

Treatment of the fracture

When the patient’s condition is stable and the wound has been dealt with, the fracture can be immobilized in one of four ways:

1. Traction.

2. Internal fixation.

3. External fixation.

4. Cast bracing.

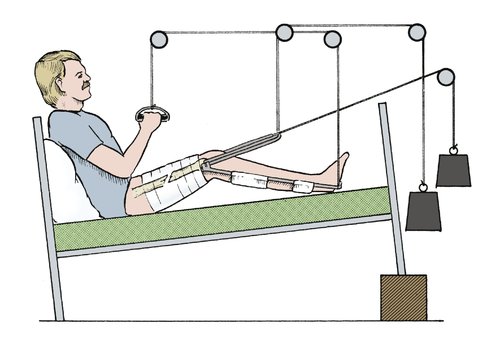

Traction. Traction used to be the mainstay of treatment of these fractures in the past. Patients were in bed for up to 3 months at times. Traction is now rarely used and is only advocated when surgery is contraindicated or in children. A single, balanced, skeletal traction apparatus is shown applied via a femoral pin in Figure 14.21.

|

| Fig. 14.21

Conservative treatment of a femoral shaft fracture with balanced sliding traction and a knee flexion piece.

|

Adequate longitudinal traction is needed for the first 24 h to overcome muscle spasm and prevent shortening and the fragments must be supported posteriorly to prevent sagging. Six kilograms (131b) is usually enough, but heavy patients need more and light patients less. Check radiographs after 24 h will show if the weight is correct; if there is overdistraction, the weight should be reduced. If there is overlap, it should be increased.

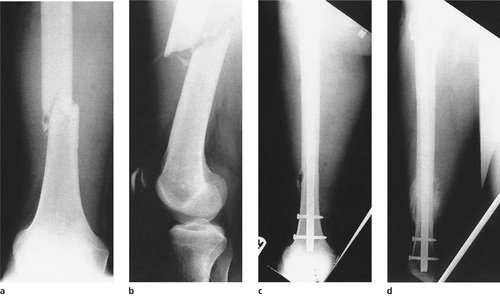

Internal fixation. An intramedullary nail is ideal for most fractures (Fig. 14.22). Fractures can be held straight and out to length by a nail, but the fixation may not be firm enough to control rotation. The advent of locking nails – where screws are inserted through the bone and nail – can now control rotation. Open reduction and fixation with a plate is not often performed owing to the extensive soft tissue exposure needed, the devitalization of the bone, and the mechanical failure of the plates.

|

| Fig. 14.22

Unstable fracture of the femur: (a), (b) before operation; (c) after fixation with a locking nail; (d) united with callus.

|

The advantages of intramedullary nailing are that it provides longitudinal stability as well as alignment and enables the patient to be mobilized rapidly enough to leave hospital within days of fracture. Disadvantages include the anaesthetic, additional surgical trauma and the risk of infection.

Intramedullary nails are inserted through the proximal or distal femur. They can be ‘reamed’ or ‘unreamed’. This simply means that the medullary cavity of the bone is enlarged to allow the nail to fit into the bone. The theoretical advantage of unreamed nails is that there is no excessive damage to the endosteal blood supply, which may further weaken the bone. By reaming the intramedullary canal, the intact endosteal blood supply is damaged throughout the length of the reamed segment and this, in conjunction with the damage to the periosteal layer, may delay healing.

Intramedullary nails can be used for comminuted fractures with shortening, provided the bone can be pulled out to length and held there. Locking nails which maintain length and rotation (p. 135) are required for such fractures.

External fixation. External fixation is used for contaminated and unstable open fractures or in the emergency situation.

Cast bracing. When a fracture treated on traction is stable and a mass of callus is visible radiologically, usually at about 6 weeks, a cast brace can be applied. Fractures in which fixation is less than 100% secure are also suitable.

The cast brace (p. 131) will enable the patient to leave hospital and begin rehabilitation more rapidly.

Fractures of the lower end of the femur

Supracondylar fractures

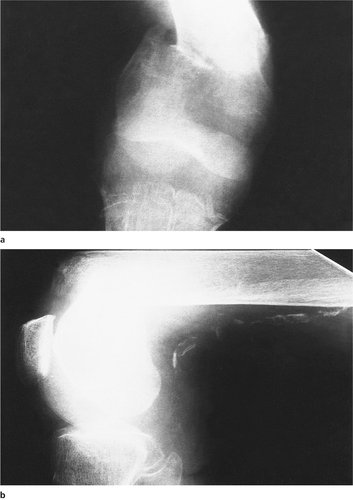

Supracondylar fractures are commonest in older patients with soft porotic bone (Fig. 14.23). The fractures are caused by either forced flexion or hyperextension and are unstable. Gastrocnemius flexes the distal fragment and increases the deformity (Fig. 14.24).

|

| Fig. 14.23

(a), (b) Supracondylar fracture of the femur in an elderly patient. Note the calcification in the femoral vessels and the extreme flexion of the distal fragment.

|

|

| Fig. 14.24

Injuries of the lower end of the femur: (a) the mechanism of flexion of the distal fragment in a supracondylar fracture; (b) slipped lower femoral epiphysis.

|

Treatment

These fractures are difficult to control conservatively because of the mobility of the distal fragment. Internal fixation is the method of choice. A blade or dynamic compression screw can be used and the newer locking plates may be of value in the porotic bone. An intramedullary implant, when inserted through the intercondylar notch of the femur, will hold the bone out to length and in the reduced position. This can be supplemented with additional screws to hold fragments together.

Slipped lower femoral epiphysis

In children, the equivalent of a supracondylar fracture is a slipped lower femoral epiphysis caused by a sharp flexion injury. Surgeons of the 19th century recorded that the fracture occurred in boys who fell backward while sitting on railings or whose feet became caught in the spokes of the wheel while riding on the back of a horse-drawn cart. Today, these injuries are less common.

Treatment

Reduction is usually easy but accuracy is important because angular deformities occur if the reduction is not perfect or the epiphysis is damaged.

Comminuted fractures

Violent trauma, particularly from motor cycle accidents, produces a very nasty comminuted fracture just above the condyle, often accompanied by a condylar fracture. The comminution is usually so great that the bone fragments cannot be reassembled and bone length is lost.

Treatment

Traction or external fixation may hold the bone out to its correct length but grafting may be required to fill the defect. Circular frames with wire fixation may hold the fragments. Again, locking plates may be of use.

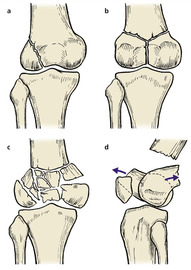

Condylar fractures

Fractures entering the intercondylar notch can break one or both condyles away from the femoral shaft, or follow an oblique line (Fig. 14.25). The relationship of the two condyles is essential for normal knee function and accurate reduction is important; even a millimetre of proximal displacement leaves a valgus or varus deformity and rotation of one condyle relative to the other interferes with flexion.

|

| Fig. 14.25

Fractures of the femoral condyles: (a) oblique fracture of the lateral condyle; (b) Y-shaped fracture into the notch; (c) comminuted fracture with (d) rotation of the condyles.

|

Treatment

Treatment depends on the degree of displacement.

Undisplaced fractures and those with negligible displacement can be treated by aspiration of the joint to remove blood, followed by rest on traction for at least 4 weeks until the fracture is sufficiently united to be safe in a cast.

Displaced fractures must be accurately reduced to avoid degenerative changes, which usually means open reduction and internal fixation.

If one condyle is involved it can be fixed onto the femur with screws. If both condyles are separated they can be fixed together, converting the lesion into a supracondylar fracture.

Oblique fractures are managed in the same way, with conservative treatment for slight displacement and internal fixation for the rest. Elderly or infirm patients can be managed conservatively.

Complications

The fragments often lose their blood supply at the time of injury or at operation. This can lead to aseptic necrosis, collapse and a gross deformity.

If the fragments are not repositioned exactly there will be a valgus or varus deformity, which may lead to osteoarthritis.

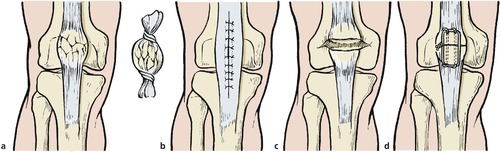

Fractures of the patella

Comminuted fractures

The patella is easily fractured by a blow to the flexed knee, often in a road traffic accident (Fig. 14.26).

|

| Fig. 14.26

Fractures of the patella: (a) stellate fracture; (b) comminuted fracture treated by patellectomy; (c) transverse fracture; (d) transverse fracture treated by tension band wiring.

|

Treatment

The shear stresses on the back of the patella are enormous and any irregularity of its surface will cause osteoarthritis in later life.

Unless the fragments can be accurately reassembled, which is usually impossible, it is best to remove the patella and encourage early movement.

Stellate fractures

A blow to the patella may crack it without displacing the fragments, like a boiled sweet broken inside its wrapper (Fig. 14.27).

|

| Fig. 14.27

(a), (b) Stellate fracture of the patella with little displacement.

|

Treatment

Stellate fractures can be managed conservatively by aspirating blood from the knee and supporting it in a long leg cast for 3 weeks, when mobilization is begun.

Transverse fractures

The patella can be split transversely by indirect violence, e.g. a forced flexion injury caused by falling with the flexed knee under the body or stepping onto a non-existent step. These injuries split not only the patella but also the quadriceps expansions on either side.

Left untreated, the fragments separate widely and quadriceps function is lost (Fig. 14.28).

|

| Fig. 14.28

(a), (b) Non-union of a transverse fracture of the patella. Note the disuse osteoporosis in the patella and underlying femur.

|

Treatment

Internal fixation is required. A tension band wire is usually adequate.

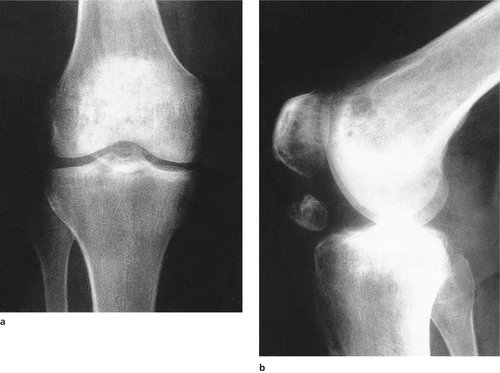

Injuries of the extensor mechanism

Rupture of the rectus femoris

Sudden violent contraction of the quadriceps is enough to tear rectus femoris transversely in its mid portion (Fig. 14.29). The patient feels sudden severe pain and a defect can be felt in the muscle.

|

| Fig. 14.29

Sites of rupture of the extensor mechanism: ( A) rectus femoris; ( B) quadriceps tendon; ( C) patella; ( D) patellar tendon.

|

Treatment

None is effective apart from the application of ice wrapped in a towel, elevation, analgesics and mobilization within the limits of comfort. The defect in the muscle remains but the functional deficit is negligible.

Ruptured quadriceps tendon

The same forces that cause transverse fractures of the patella also rupture the quadriceps tendon above the patella.

Treatment

Ruptured quadriceps tendons must be repaired surgically or the defect will widen and quadriceps power will be lost.

Ruptured patellar tendon

The patellar tendon may also be ruptured by a forced flexion injury and this, like the quadriceps tendon, must be repaired. Very rarely, the tendon may pull a fragment of bone from the lower pole of the patella.

Treatment

The defect must be repaired if a serious weakness and extensor lag are to be avoided.

Dislocation of the patella

The patella can be dislocated by a sharp twisting movement of the knee in very slight flexion (Fig. 14.30) and is common in adolescents, particularly girls with loose ligaments. The dislocation often used to occur on the dance floor during the Charleston, the twist and their successors. The patella sometimes reduces itself at once, but if it remains dislocated, the patient will remember seeing the kneecap lying on the outer side of the knee and may report that the ‘knee dislocated’ (Fig. 14.31).

|

| Fig. 14.30

Dislocation of the patella: (a) the patella can be dislocated by sharp twisting movements; (b) dislocation accompanied by a tear in the medial capsule.

|

|

| Fig. 14.31

A dislocated patella.

|

On examination soon after a dislocation, the knee will be swollen because of the haemarthrosis and there will be tenderness on the medial side of the patella because the medial structures are torn (medial patella femoral ligament).

Radiographs will show a haemarthrosis, perhaps with a fat–fluid level (see Fig. 5.1) and sometimes an osteochondral fracture. This fracture can be an avulsion fracture from the medial side of the patella or from the lateral femoral condyle.

In over 70% of cases an underlying abnormality is found. These include joint hypermobility, patella alta, patella maltracking and axial malalignments.

Complications

In some patients the patella continues to dislocate with progressively less trauma. Recurrent dislocation of the patella is described on page 426.

If the articular surface is disrupted, patellofemoral osteoarthrosis is likely.

Treatment

All blood should be aspirated to help reduce pain. Immobilization of the knee will weaken the quadriceps further and early active rehabilitation is preferable.

If an osteochondral fracture is present, the fragment must be dealt with. Large fragments in the weight-bearing area should be fixed back into their bed and small ones removed. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis or the size of the fragment, the joint should be examined arthroscopically. Fat within the aspirate should alert one to the osteochondral injury.

If the patella has dislocated more than three times a stabilizing operation will probably be required (p. 426).

Fractures within the knee

Osteochondral fractures

Slivers of bone can be sheared off the articular surfaces by twisting stresses under load, or chipped off by direct trauma. Indirect violence is commoner in adolescents, and direct violence in young adults. Both are accompanied by haemarthrosis, and fat from the cancellous bone forms a fat–fluid level on the lateral radiograph.

The diagnosis is often missed because the loose body and the defect on the articular surface may be small and escape detection. If left untreated, the fragment will present later as a loose body.

Treatment

Large fragments should be reattached and small ones removed.

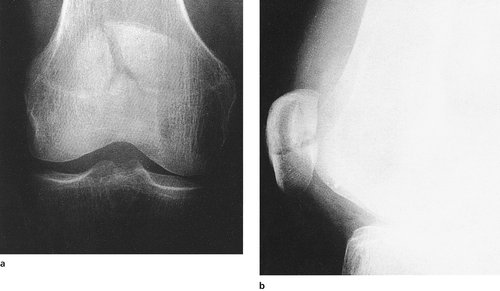

Fractures of the tibial plateau

If the knee is struck violently on the lateral side, one of two things can happen:

1. The medial ligament tears.

2. The lateral tibial plateau fractures.

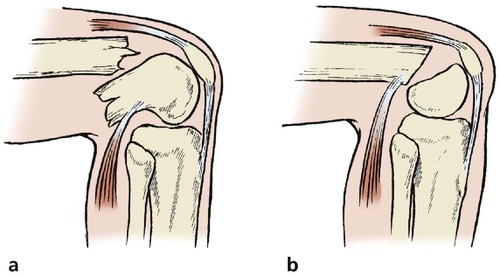

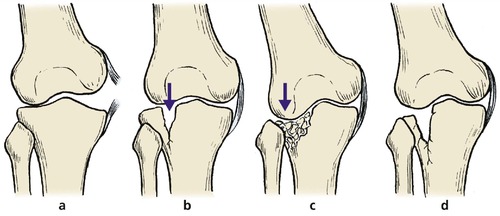

If the bone fractures, four patterns of fracture can occur (Fig. 14.32):

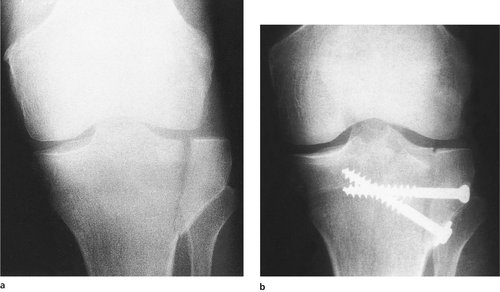

1. The lateral condyle acts like a blunt chisel and splits the lateral tibial plateau vertically (Fig. 14.33).

|

| Fig. 14.33

(a) A vertical split in the lateral plateau; (b) treated by internal fixation. The gap has not been completely obliterated and the depressed fragment has not been elevated. This unsatisfactory result illustrates the difficulties caused by this fracture.

|

|

| Fig. 14.32

Injuries from a force to the lateral side of the knee: (a) medial ligament rupture; (b) vertical split in the lateral plateau; (c) crush fracture of the lateral plateau; (d) crush and split of the lateral plateau.

|

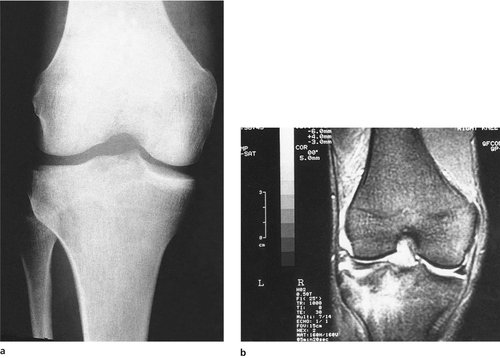

2. Part of the tibial plateau may be thrust downwards into the tibia producing a depressed plateau fracture (Fig. 14.34).

|

| Fig. 14.34

(a) Anteroposterior radiograph of a depressed plateau fracture. The fracture is hard to see. (b) MRI scan of the same fracture showing the full extent of the damage.

|

3. Both of these can occur together.

4. The whole tibial plateau may be depressed (Fig. 14.35).

|

| Fig. 14.35

Depression of the lateral plateau with impaction.

|

The full extent of the fracture may not be apparent on a plain radiograph, and CT or MRI scanning may be needed to define the anatomy of the fracture.

Treatment

If a large fragment is split off the tibia it must be screwed back to restore the contour of the tibia. Large depressed fragments can be elevated to reconstitute the bone surface but a cavity will remain at the site of the fragment because the bone was crushed. The chondral surface should be reconstructed and the underlying cavity must be filled with a cancellous bone graft as support.

If there is only a slight depression in the plateau, the fracture can be managed conservatively with early mobilization. The defect will fill in with fibrocartilage and the patient will probably achieve good function despite a slight valgus deformity. This is adequate for an infirm patient with few physical demands on the limb but those younger, requiring a more physical lifestyle, may need reconstruction.

Ligament injuries at the knee

The knee depends heavily on its ligaments for stability. The hip and the shoulder move freely in any direction, the range being limited by the shape of the bones as much as the ligament. The knee has a very restricted range of movement from 0 to 150° in one plane only, and it is the ligaments which prevent unwanted movement.

Because ligaments never heal soundly or regain their normal strength, as bone does, ligament injuries of the knee have more serious long-term implications for the patient than a fracture of the tibia or femur.

Ligaments do not show on radiographs and patients with serious injuries are sometimes sent home from the accident department with the good news that ‘no bones are broken’. If the patient felt something break in the leg but the bones are intact, there is a major ligament injury until proved otherwise.

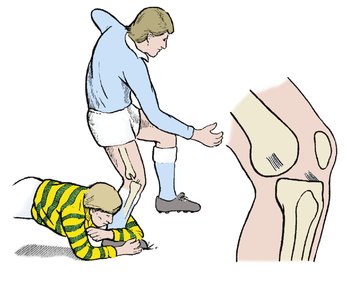

Anterior cruciate rupture

The anterior cruciate limits forward movement of the tibia on the femur and is often ruptured in sporting activities by a sharp twisting movement, or by a tackle which pushes the upper part of the tibia forwards (Fig. 14.36).

|

| Fig. 14.36

Mechanism of injury of the anterior cruciate ligament.

|

Acute anterior cruciate rupture is a common injury. About 80% of acute haemarthroses are caused by this lesion, and about 60% of these patients will have other associated injuries.

The patient often feels something ‘go’ in the knee at the moment of injury and may think a bone has broken, particularly as breaking a cruciate makes a snapping sound that is audible to those nearby. The patient is unable to carry on and feels the knee is very weak. The event is so dramatic that patients can remember the incident with great clarity many years later.

The instability is easy to assess immediately after injury, before bleeding has occurred and the tissues have swollen. Within 15 minutes the instability is difficult to assess because of swelling and protective muscle spasm.

Natural history

There are three possible outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Roughly one-third of patients with anterior cruciate rupture achieve a good result without operation and lead a normal life, including sport, without any difficulties.

In another third, the knee becomes so unstable that it gives way even when walking over level ground. The instability may be so great that the patient is even afraid of crossing a road in case they fall. These patients need reconstruction of the ligament (p. 420).

The remaining third experience symptoms of instability which interfere with life to a variable degree. Some are happy to give up sport or simply to avoid those activities that cause symptoms. Others prefer a reconstruction.

There is no way of knowing for certain what the long-term outcome will be in any one patient on the day of injury. Solidly built rugby players with big bones are likely to have fewer symptoms of instability than lightly built female netball players with slim bones and generalized ligamentous laxity, but apart from these groups it is hard to give a prognosis.

Because the outcome cannot be accurately predicted, it is better to opt for conservative treatment in most patients and to defer reconstruction until the outcome is known.

Treatment

Conservative. This consists of removing blood from the knee by thorough aspiration or arthroscopy. Arthroscopy is hazardous in patients with ligamentous and possible capsular injury and should only be undertaken by an experienced arthroscopist. It may nevertheless be needed both to remove blood and to assess the condition of the intra-articular structures.

Once blood has been removed, physiotherapy can be instituted to build up all muscle groups, especially the hamstrings. The hamstrings prevent excessive forward movement of the tibia and are therefore more important than the quadriceps, which work in the opposite direction (exacerbating the anterior draw).

There is no need to apply a cast to a patient with an isolated rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament, provided the diagnosis is certain. In some circumstances a cast may be appropriate as a pain-relieving measure, particularly if the patient has to travel a long distance after injury.

Operative. Effective repair of the anterior cruciate ligament is impossible and has largely been abandoned. The ligament crosses the synovial cavity of the knee, and its torn ends, which look like pieces of soggy string, are devitalized at the moment of injury and retract very rapidly. Apposing two such structures with inert non-absorbable suture material does not produce a functioning anterior cruciate ligament.

If operation is to be undertaken it should be a full reconstruction, of the type described on page 421. This should only be advised immediately after injury if the patient needs to return to top class sport without delay, e.g. a professional footballer, or for a patient with gross instability.

Avulsion of the anterior cruciate

In young patients the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate may be avulsed instead of the ligament tearing (Fig. 14.37).

|

| Fig. 14.37

(a) Avulsion of the anterior cruciate attachment of the tibia; (b) the fragment has not united in its bed.

|

Treatment

The fragment should be accurately replaced by manipulation, or by reduction and fixation under arthroscopic control, and immobilized for 6 weeks. The results are unpredictable because the avulsed ligament is often devitalized.

Medial collateral ligament

Complete tears of the medial collateral ligament are usually associated with a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament. Isolated tears of the medial collateral are caused by a pure valgus strain. In the UK, blows to the side of the knee from impetuous Labradors and other large dogs are a frequent cause.

Isolated lesions of the medial collateral usually heal well without operation. Lesions near the femoral attachment can heal with the formation of a flake of new bone, which can be seen radiographically, but the site of injury may remain tender for many years. Tenderness associated with the radiological signs of an old medial ligament injury is known as ‘Pellegrini–Stieda disease’ but it is not a disease in the accepted sense.

Treatment

Although isolated partial medial collateral ligament tears probably heal well whatever is done, it is prudent to apply a long leg cast brace from groin to ankle for about 6 weeks. This brace should allow a degree of knee flexion as this aids ligamentous healing. This brace can be modified to a removable brace to aid with physiotherapy.

Tears of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) together should be immobilized in a cast for 6 weeks, as above, unless it is decided to proceed to immediate anterior cruciate reconstruction, which may be combined with repair of the medial collateral ligament. It is often better to allow the MCL to heal first and then come back and do an ACL reconstruction, if indicated, in the future.

Posterior cruciate ligament

The posterior cruciate ligament can be torn in three ways:

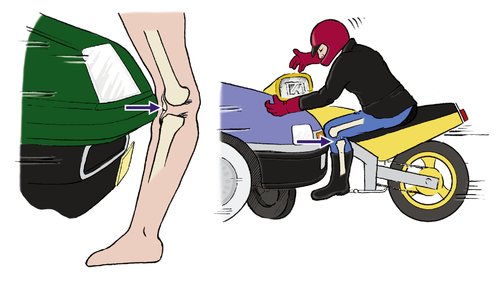

1. A blow to the upper end of the tibia when the knee is flexed, as when seated on a motorcycle or in the front seat of a car involved in a head-on collision (Fig. 14.38).

|

| Fig. 14.38

Mechanism of rupture of the posterior cruciate ligament by (a) hyperextension: (b) impact to the upper end of the tibia with the knee flexed.

|

2. By hyperextension.

3. In combination with other ligament injuries (dislocations).

On examination soon after injury, there will be a haemarthrosis and a backward sag of the tibia relative to the femur. This is not disguised by muscle spasm.

Natural history

Most patients make an excellent recovery from an isolated posterior cruciate ligament rupture without treatment and there are many international athletes competing at their former level with posterior cruciate insufficiency.

A few patients, usually those with an associated posterior capsular rupture or damage to the posterior lateral ligamentous structures, do very badly but there is no way of knowing on the day of injury which patients will fall into this category.

Treatment

Conservative. Conservative treatment consists of removing blood from the joint by careful aspiration or arthroscopy and then immobilizing the knee in extension. Following removal of the plaster, a vigorous quadriceps exercises regimen is begun. These should be continued until the quadriceps is more powerful on the side of the injured limb than on the side of the uninjured opposite limb.

Operative. Operation should only be considered if there is considerable instability, associated damage to other ligamentous structures, or when the tibial insertion of the posterior cruciate has been avulsed with a block of bone. If such a block of bone is present it can be reattached with a screw using the posterior approach to the knee.

Most patients manage well without a posterior cruciate ligament and it is usually best to treat the lesion conservatively and perform a late reconstruction if necessary.

Lateral collateral ligament

The lateral collateral ligament is seldom injured on its own, except in lacerations. The ligament joins the femur to the fibula, not the tibia, and it is not as important as the other ligaments. When injured, there is, however, a high incidence of damage to the common peroneal nerve (30%). It is often injured together with the other lateral stabilizers of the joint (popliteus, arcuate, capsule, hamstrings).

Treatment

Early operative repair is preferable as conservative management is often unsatisfactory.

Dislocation of the knee

Complete separation of the tibia from the femur requires enough trauma to tear at least two of the four major ligaments. Trauma as great as this is enough to damage the popliteal vessels and nerves. Both vascular and neurological functions must be assessed carefully and recorded so that any deterioration will be noticed. Damage to the popliteal vessels occurs in 50% of cases and an angiogram is mandatory if there is doubt about the peripheral vascularity. Exploration of the popliteal artery and repair should be performed as an emergency as there is a high chance of an amputation if this is delayed more than 6 hours from the time of the injury.

Treatment

Management consists of attention to the nerves and vessels and watching for compartment syndromes. Accurate reconstruction of a dislocated knee is difficult. Reattachment of avulsed ligaments is often possible but reconstructing both the cruciates is very difficult. Conservative treatment involves immobilizing the knee for 6 weeks in a plaster cast. Care is taken to ensure there is no displacement of the joint while it is in plaster. Reconstruction may be required later.

Conservative treatment of the ligaments is indicated if damage to the vessels or nerves is suspected but definite damage to the vessels and nerves is an indication for immediate repair of those structures.

Meniscal injuries

Meniscal injuries are described on page 413.

Haemarthrosis of the knee

Management

Bleeding into the knee always indicates a serious injury. Roughly 80% of patients with a haemarthrosis have a major ligament injury, usually the anterior cruciate ligament; 15% are as a result of a patella dislocation and 5% from other causes including osteochondral fractures and peripheral third meniscal tears. The principles of managing a haemarthrosis are twofold:

2. To make a diagnosis.

Blood in the knee acts like superglue. If not removed, it will clot inside the joint and cause intra-articular adhesions that limit mobility. Even if it does not clot, blood is an irritant and causes an intense synovitis that takes many weeks to resolve. For both these reasons, rehabilitation is much more rapid if the joint is free of blood.

Treatment

Because a haemarthrosis always indicates a serious injury, a diagnosis must be made and treatment begun as soon as possible. Arthroscopy may be needed to remove blood and confirm the diagnosis but this is difficult.

If arthroscopy is not available, blood should be aspirated from the joint as thoroughly as possible and the aspirate examined for fat globules. Fat can only enter the knee from a fracture site or a contused area of subcutaneous fat communicating with the knee. The presence of fat in the aspirate indicates a serious injury. A fat–fluid level may also be visible on a lateral radiograph (see Fig. 5.1).

If the diagnosis remains unclear the knee should be examined by MRI or CT. It is not acceptable to immobilize the knee in a cast or firm supporting bandage and refer the patient to the fracture clinic 2 weeks later. This allows adhesions to form within the joint, the muscles waste and definitive treatment such as replacement of osteochondral fragments is delayed.

Fracture of the tibia and fibula

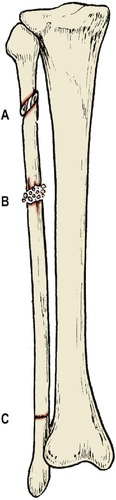

Fracture of the fibula alone

The fibula can be fractured alone in three ways (Fig. 14.39):

1. Direct trauma to the outer side of the leg, which produces a transverse or a comminuted fracture.

2. Twisting injuries, which produce a spiral fracture. Beware of an isolated spiral fracture at the upper end of the fibula: it may be associated with a fracture of the tibia at the ankle. This combination is a Maisonneuve fracture and will do badly with conservative treatment. The ankle must be examined radiologically in every patient with an apparently isolated fracture of the fibula, so that a tibial fracture is not missed (Fig. 14.40). Maisonneuve, Monteggia and Galeazzi fractures have much in common.

|

| Fig. 14.40

A fracture of the fibula associated with a medial malleolar fracture. This was caused by a pronation injury of the foot.

|

|

| Fig. 14.39

Isolated fracture of the fibula: ( A) spiral fracture; ( B) comminuted fracture from direct trauma; ( C) fatigue fracture.

|

3. Repeated stress in long-distance runners can cause a fatigue fracture, usually just above the inferior tibiofibular ligament (see Fig. 15.2).

On examination, the fracture site will be tender, and perhaps bruised. Dorsiflexion of the ankle may be painful because the fibula takes part in the ankle joint and movement of the ankle causes movement of the fracture site. As long as the tibia remains intact the patient can bear weight through the limb, but will avoid the heel-strike phase of gait if possible.

Treatment

If the fracture is undisplaced and the tibia is intact, no immobilization is required unless movement is painful. A cast may then be required to immobilize the ankle.

Fatigue fractures need immobilization.

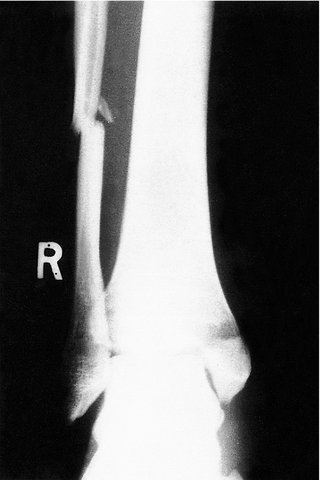

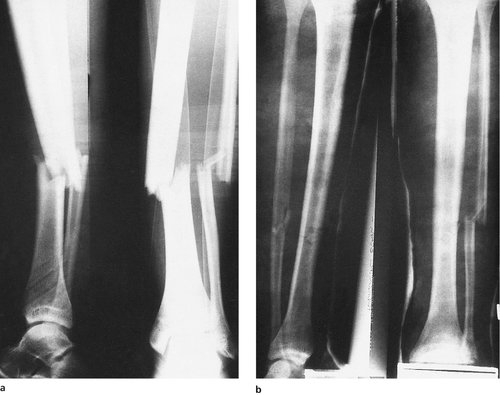

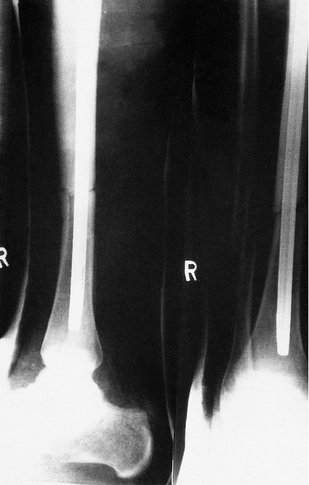

Fracture of the tibia alone

The tibia can be broken, leaving the fibula intact, in three ways (Fig. 14.41):

1. Direct trauma.

2. Very rarely by twisting injuries.

3. Repeated stress can cause a fatigue fracture at the junction of the middle and upper thirds. The lesion is commonly seen in long-distance road runners, hurdlers, and male ballet dancers who jump to excess.

|

| Fig. 14.41

Isolated fractures of the tibia: ( A) fatigue fracture at the upper end; ( B) comminuted fracture; ( C) spiral fracture; ( D) ‘boot top’ fracture.

|

Note: Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia is not a true fracture; it is dealt with on page 364.

Treatment

The fracture is treated in the same way as a fracture of both bones. It might seem helpful to have the fibula intact, but this is not so because the intact fibula holds the ends of the tibia apart (Fig. 14.42 and Fig. 14.43) and it may be necessary to cut the fibula in order to achieve satisfactory alignment of the tibia.

|

| Fig. 14.42

Isolated fracture of the tibia. If the tibia alone is fractured, the intact fibula can hold the ends apart.

|

|

| Fig. 14.43

In this isolated fracture of the tibia, the fracture has united with loss of length. The fibula is thus relatively long, causing dislocation of the head of the fibula.

|

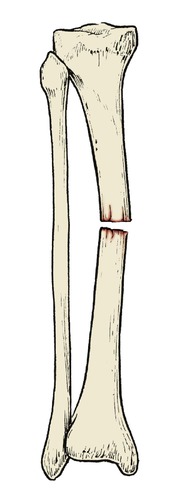

Fractures of both tibia and fibula

Fracture of both the tibia and fibula is a common injury and occupies much orthopaedic time. Road traffic accidents and twisting injuries on the sports field are the commonest causes.

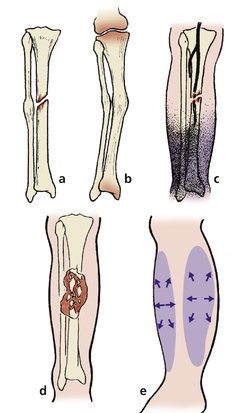

Complications (Fig. 14.44)

• Non-union.

• Delayed union.

• Malunion.

• Vascular damage.

• Soft tissue damage.

• Skin loss.

• Compartment syndrome.

|

| Fig. 14.44

Complications of fractures of the tibia and fibula: (a) non-union of the tibia with union of the fibula: (b) malunion with osteoarthrosis of knee and ankle; (c) ischaemia of the foot due to vascular damage; (d) skin necrosis over the fracture; (e) compartment syndrome.

|

If non-union occurs, plating and grafting will be required.

Delayed union is common in the same group of patients who develop non-union.

Malunion is also common and causes increased wear on the knee and ankle, which in turn causes osteoarthritis.

Vascular damage may lead to gangrene of the foot and ankle. The circulation must always be observed carefully if it is likely that the vessels are seriously stretched or contused at the moment of impact, and the findings recorded. Neurological damage often accompanies vascular injury.

Soft tissue damage around a fractured tibia and fibula interferes with the final function of the leg; management of the soft tissues is often more difficult than treating the fracture.

Skin loss over the subcutaneous surface of the tibia presents a particular problem. Exposed bone does not heal well and it is often necessary to seek the help of a plastic surgeon to achieve skin cover. Any skin cover is better than none, but a free flap transferred with its own blood supply by microvascular surgery may be the most satisfactory solution. A cross-leg flap is an alternative.

Compartment syndromes. Closed fractures cause bleeding and oedema in the closed fascial spaces and a compartment syndrome with ischaemic fibrosis of the muscles if untreated. If a patient develops a tense calf with loss of passive extension and diminished sensibility following a fracture of the tibia, decompression of all four compartments of the leg is required. This can conveniently be done by excising a 5 cm segment of the fibula with its periosteum, but a wide fasciotomy through a long skin incision is equally effective.

Treatment

Treatment begins at the scene of the accident.

Immediate care. The wounds of an open fracture should be covered with the cleanest material available. For transport to hospital the injured limb can be supported by bandaging it to the other leg but air splints are better and readily available in most ambulances. The blood loss from a fractured tibia is between 1 and 3 units and transfusion is not required unless there is haemorrhage from elsewhere.

Definitive treatment. The fragments must be held in the reduced position for 10–16 weeks by one of the following techniques:

1. Cast immobilization.

2. Internal fixation.

3. External fixation.

Very basic summary of choice of management in fractures of the tibia and fibula:

• Stable – cast immobilization.

• Unstable – internal fixation.

• Contaminated and unstable – external fixation.

Cast immobilization. The fracture is reduced under general anaesthesia and a cast applied from groin to toe (Fig. 14.45). Until skilled in plastering, apply the cast in stages, beginning with a gaiter round the shin and extending this above and below to include the knee and foot separately. The circulation in the foot must be carefully observed for the first 24 h.

|

| Fig. 14.45

(a) Transverse fracture of the tibia and fibula treated by (b) closed reduction and plaster immobilization.

|

The fracture should be examined radiologically immediately after the reduction, 24 h later and at 1 week, 2 weeks and then monthly after injury. A walking heel can be applied and weight-bearing permitted after a month if the fracture is stable and the position satisfactory.

Internal fixation is indicated for unstable fractures and patients with multiple fractures (p. 132). Plates and screws, screws alone, wires or intramedullary nails can all be used; the choice of technique depends upon the pattern of the fracture (Fig. 14.46). Although rigid anatomical fixation is attractive, the operation is a second injury to the limb and may be followed by infection.

|

| Fig. 14.46

Internal fixation of a transverse fracture of the tibia with an intramedullary nail. The nail is too small to hold rotation but alignment is maintained. A locking nail would have been more secure.

|

External fixation is needed if there is a dirty wound or extensive skin loss. The fixation is not as rigid as a plate or intramedullary nail but will maintain reduction and length until the soft tissues have healed. Although the fixation apparatus looks gruesome it is well tolerated by patients.

Choice of treatment depends on the shape of the bone ends and the state of the soft tissues.

Transverse fractures of the tibia are stable if the ends can be hitched. Provided that the fracture is truly stable on longitudinal pressure, full weight-bearing can be permitted in a long leg cast as soon as the patient can tolerate it. The cast can be changed to a patellar tendon-bearing or below-knee cast as soon as callus is visible and the fracture appears firm, usually about 8 weeks from injury. The cast can be discarded altogether after about 12 weeks.

Spiral fractures are caused by twisting injuries and are always unstable (Fig. 14.47). The instability is worse if one of the bone ends is broken off as a ‘butterfly’ fragment. Internal fixation by plating or intramedullary nailing is usually needed for these fractures.

|

| Fig. 14.47

A very unstable spiral fracture of the tibia and fibula.

|

Segmental fractures, in which the tibia and fibula are fractured in two places, with a mobile central fragment, are very unstable and best treated by a locking intramedullary nail.

Boot-top fractures. A ski boot immobilizes the ankle so firmly that rapid deceleration breaks the leg at the top of the boot. These fractures are unstable and usually need internal fixation.

Contaminated fractures are frequently seen after road traffic accidents and are usually comminuted and unstable.

The wound must be meticulously cleaned of all foreign material and dead tissue under general anaesthesia.

External fixation is ideal for contaminated fractures, provided that the proximal and distal fragments are large enough to hold the pins needed for sound fixation. Locked reamed or unreamed intramedullary nails are used frequently with excellent results. If neither of these two methods is possible, skeletal traction can be applied by a calcaneal pin. When the wounds are healed the patient can either be discharged with the external fixation device still in position or after the fractures have been stabilized.

Internal fixation with a plate and screws is very occasionally advised for contaminated wounds on the basis that infection is less likely to persist in a stable skeleton than an unstable fracture. This is an interesting but very controversial subject. It is much safer, especially in examinations, to remember that internal fixation should only be used on clean and healthy tissues.

‘ Technically compound’ fractures, in which the skin is punctured from inside, must be cleaned and debrided meticulously because dirt and clothing can be drawn into the wound at the moment of injury. They are just as dangerous as any other open fractures.

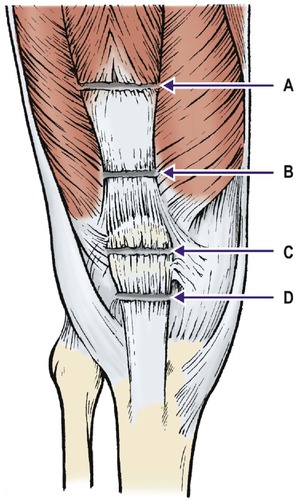

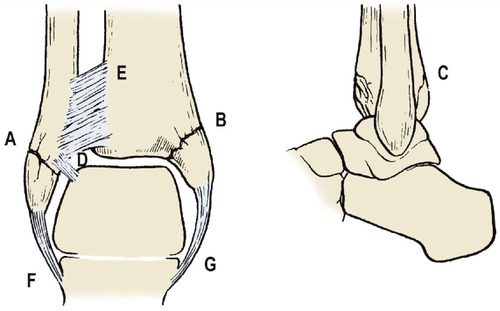

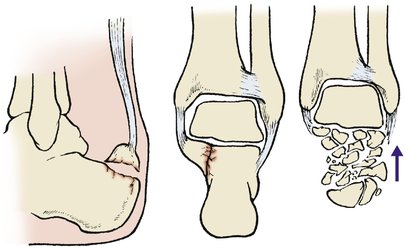

Injuries of the ankle

In 1769 Sir Percival Pott of St Bartholomew’s Hospital described a fracture of the lower end of the fibula with lateral displacement of the talus. ‘Pott’s fracture’ is still often applied loosely to any fracture dislocation of the ankle. This is confusing because the type that Pott described is quite rare. There are many different types of fracture caused by a variety of mechanisms, and each needs to be treated differently.

Bones may be broken in the ankle at three points:

1. The medial malleolus of the tibia.

2. The lower end of the fibula, including the lateral malleolus.

3. The ‘posterior malleolus’, or posterior margin of the tibia.

Three ligaments may be torn (Fig. 14.48):

1. The inferior tibiofibular ligament.

2. The medial ligament.

3. The lateral collateral ligament.

|

| Fig. 14.48

Structures that may be injured at the ankle: ( A) lateral malleolus; ( B) medial malleolus; ( C) posterior malleolus; ( D) anterior inferior talofibular ligament; ( E) inferior tibiofibular syndesmosis; ( F) lateral ligament; ( G) medial ligament.

|

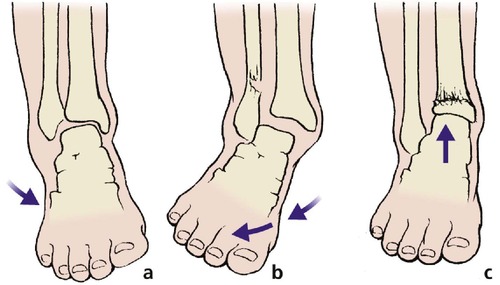

Four forces may contribute to the injury (Fig. 14.49):

1. Abduction.

2. Adduction.

3. External rotation.

4. Vertical compression.

|

| Fig. 14.49

Forces that may injure the ankle: (a) adduction; (b) abduction; (c) upward compression.

|

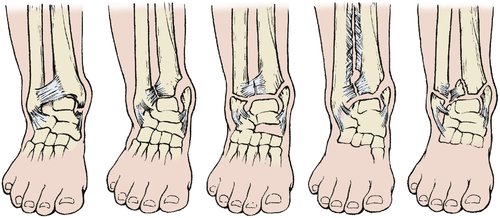

Five grades of severity are seen (Fig. 14.50):

1. Ligament injury alone.

2. Ligament injury plus one malleolus.

3. Ligament injury plus two malleoli.

4. Ligament injury plus all three malleoli.

5. Ligament injury plus diastasis of the inferior tibiofibular joint plus fracture.

|

| Fig. 14.50

Severity of ankle fracture. Ligaments may be ruptured and bones broken around the ankle in many different combinations.

|

Management

Treatment can be conservative or operative. Both methods consist of reversing the movement that caused the fracture and holding the foot reduced. In some patients a good position will be achieved by manipulation alone but internal fixation is needed if the fractures are unstable or the joint surface of the ankle is disturbed.

The choice between internal fixation and conservative treatment is often difficult and depends on the type of the fracture, its stability and the patient’s age.

Conservative treatment

Fractures treated conservatively should be re-examined radiologically at 10 days to be sure that the position has not slipped, and the plaster retained for at least 8 weeks. If the fracture is stable, weight-bearing can be permitted at about 4 weeks. Physiotherapy after the plaster is removed will help to restore ankle movement.

Internal fixation

There are two principal objectives:

1. To reconstitute the joint surface.

2. To create a stable joint.

If these two aims can be achieved, the ankle can be left free and early movement commenced. If not, a cast is needed.

Complications

The main complications of fracture dislocation of the ankle are malunion and secondary osteoarthritis. Because the ankle is at the lowest point of the body it takes all the body’s weight and even a slight imperfection of the joint causes degenerative change. Nevertheless, if alignment is good (Fig. 14.51), function may be surprisingly good.

|

| Fig. 14.51

(a), (b) Malunion following a severe fracture dislocation of the ankle. The function was surprisingly good because the foot was correctly aligned on the tibia in the anterior posterior view.

|

Abduction injuries

Violent abduction of the ankle can tear the deltoid ligament or pull the medial malleolus away from the rest of the tibia. The abduction force also knocks the lower end of the fibula off at the level of the joint surface, but leaves the inferior tibiofibular ligaments intact. The damage on the medial side causes much soft tissue swelling.

Treatment

These fractures are difficult to hold in a cast. The initial position may be satisfactory but as the swelling subsides the cast becomes loose and the fragments can slip. Internal fixation is more reliable and allows earlier mobilization.

Adduction injuries

Pure adduction injuries are rare because there is usually an element of rotation if the deforming force is strongly applied.

Sprained ankle

The commonest ankle injury of all, a sprained ankle, is a partial tear of the anterior inferior talofibular ligament caused by sudden adduction of the foot when the ankle is plantar-flexed. The patient is aware of pain at the time of injury, and on clinical examination there is tenderness over the ligament. There may be a haemarthrosis as well.

Treatment. A firm elastic support is usually sufficient to relieve the pain but some patients need a below-knee cast.

The pain settles substantially after 10 days, but it will be uncomfortable for 8–12 weeks. The ankle may be painful if it is twisted accidentally for up to 2 years afterwards.

Lateral collateral ligament rupture

Lateral collateral ligament rupture can occur without a fracture. The radiograph is normal but the diagnosis can be made by the history, clinical examination and a stress radiograph to demonstrate abnormal mobility.

Treatment. Protected mobilization is required for 4–6 weeks.

Complications. Recurrent instability of the ankle can follow rupture of the lateral collateral ligament and may require a reconstructive procedure later (p. 431).

Avulsion of the lateral malleolus

The lateral collateral ligament of the ankle is strong enough to avulse a fragment of the lateral malleolus.

Treatment. The injury can be regarded as a severe sprain rather than a fracture of the fibula but pain can be so severe that a below-knee cast is needed. If the fragment is more than 1 cm wide or displaced, it should be replaced and fixed.

Fracture of the malleoli

In adduction injuries the medial malleolus is pushed away from the rest of the tibia and may break off. The lateral malleolus may be avulsed and the fragment is sometimes substantial.

Treatment. Fractures with no displacement can be treated conservatively in a below-knee cast. Displaced or unstable fragments will need internal fixation.

External rotation injuries

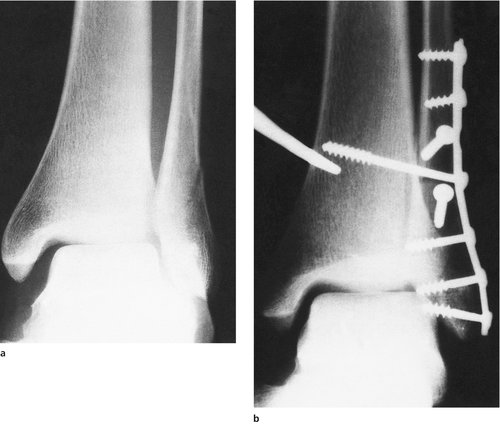

External rotation of the foot pushes the talus against the lateral malleolus (Fig. 14.52). The deltoid ligament may be torn or the medial malleolus avulsed, but the lateral side is more severely damaged. The fibula may be broken at the level of the inferior tibiofibular ligament and the back of the tibia, or ‘posterior malleolus’, may also be broken. The fracture of the fibula is sometimes well above the ankle.

|

| Fig. 14.52

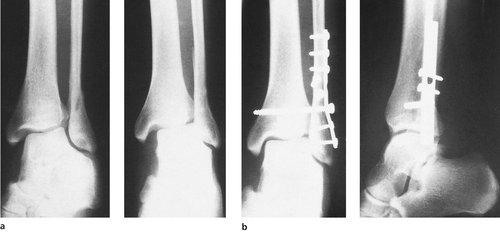

Anteroposterior view of external rotation injury of ankle before (a) and after fixation (b). The talus and lateral malleolus are shifted laterally. Note: The diastasis screw was unnecessary once the fibula had been held reduced.

|

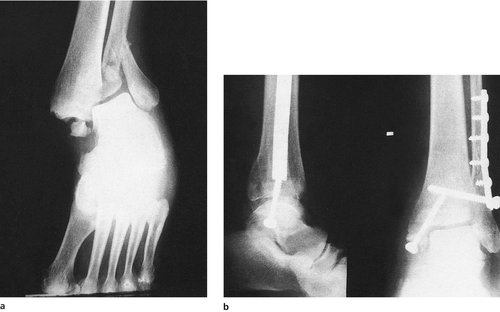

Treatment. These fractures are very unstable and internal fixation is usually needed to restore the inferior tibiofibular joint and the surface of the ankle joint (Fig. 14.53). If the posterior malleolus involves more than one-quarter of the joint surface, it will also need to be reduced and fixed.

|

| Fig. 14.53

(a), (b) Anteroposterior and lateral views of an external rotation fracture dislocation of the ankle with a small fracture of the posterior malleolus. (c), (d) The same fracture after open reduction and internal fixation of the lateral malleolus.

|

Diastasis

In very severe external rotation injuries the inferior tibiofibular joint may be completely disrupted with diastasis and a fracture higher up the fibular shaft (Fig. 14.54).

|

| Fig. 14.54

(a) Anteroposterior view of an external rotation and abduction fracture with fracture of the fibula, posterior malleolus and medial malleolus. (b) The result of open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture in (a).

|

Treatment. The diastasis should be closed with a transverse screw after fixation of the fibular shaft fracture (Fig. 14.55). This screw must be removed after about 8 weeks, when the ligament has healed. There is a little movement between the tibia and fibula in the normal leg, which is not possible with a screw across the syndesmosis. If the screw is not removed, either it will break through fatigue or the ankle will be stiff.

|

| Fig. 14.55

(a) External rotation and abduction fracture of the fibula, with diastasis treated by internal fixation (b).

|

Vertical compression injuries

Vertical compression or hyperextension of the ankle can cause a comminuted crush fracture of the anterior cortex of the tibia. The fracture is often caused by a sharp upward movement of the foot when it catches on a protruding object as the patient is falling from a height.

Treatment. Because the joint surface of the tibia is crushed and the fracture is unstable, it must be held with a plate and, if necessary, a bone graft to fill the defect. The aim is to produce a joint surface in the normal relationship to the talus. An articulated external fixator can be used to hold the bone out to length at the same time as allowing the ankle to move.

Achilles tendon rupture

The Achilles tendon can be torn by a forward lunge on the sports field or squash court. These are the same movements that tear the head of the gastrocnemius (p. 286). The patient will feel as though somebody has kicked him on the Achilles tendon and there are legendary stories of the victim feeling a kick, turning round and punching the person behind – usually a policeman – in retribution.

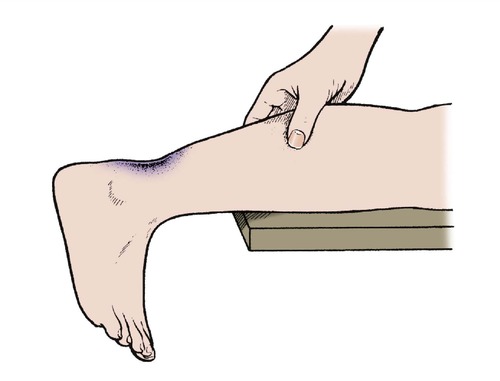

On examination, there is swelling around the tendon but a defect will be felt in the tendon. The ‘squeeze’ test will be positive because the fascial sheath is ruptured (Fig. 14.56).

|

| Fig. 14.56

The squeeze test for rupture of the Achilles tendon. If the tendon is ruptured, the foot does not move when the calf is squeezed.

|

Treatment

Treatment can be conservative or operative but both methods rely on holding the torn ends of the tendon together until healed, and this can be done in a below-knee cast with the ankle in full flexion. Operation is difficult because the ends are not cut cleanly across and at operation look like two untidy shaving brushes, but it is generally preferred, especially for athletes.

Cast immobilization is required for both conservative and operative treatment. A below-knee cast in full ankle flexion is maintained for 4 weeks and then changed to bring the foot halfway up to neutral for a further 2 weeks, when the cast is removed. A further walking cast is used for 2 weeks and then the patient starts on an intensive physiotherapy regimen. Recently a removable brace has been used which holds the foot in the desired position but allows physiotherapy to start sooner.

Ultrasound to reduce the swelling and physiotherapy to restore movement can be started when the cast is removed, but no vigorous activity or sport should be permitted until a full range of movement has been restored. This is likely to be at least 16 weeks from injury and usually longer.

Fractures of the talus and hindfoot

Fractures of the talus

The talus can be fractured by twisting injuries to the foot, violent dorsiflexion or impact from below.

The talus takes part in the ankle, subtalar and midtarsal joints. The function of all these joints is affected if the talus is fractured.

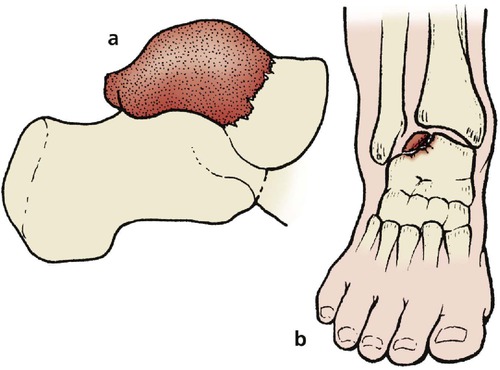

There are three types of fracture of the talus (Fig. 14.57):

1. Fractures of the body of the talus.

2. Fractures through the neck of the talus.

3. Osteochondral fractures.

|

| Fig. 14.57

Fractures of the talus: (a) a fracture of the neck may cause aseptic necrosis of the body; (b) osteochondral fracture of the talus.

|

Complications

Fractures of the neck of the talus are serious and often followed by complications:

1. Skin necrosis if the talus is extruded subcutaneously, when it stretches the skin severely.

2. Non-union.

3. Aseptic necrosis because the blood supply of the body of the talus is interrupted by a fracture through its neck.

4. Late osteoarthrosis of the subtalar and talonavicular joints.

5. Unrecognized osteochondral fragments may need to be removed later as loose bodies.

Treatment

Fractures of the neck should be reduced in good position, by open reduction and internal fixation if necessary, and protected from stress until united.

Fractures of the body cannot be reduced accurately and may be treated by early mobilization within the limits of pain.

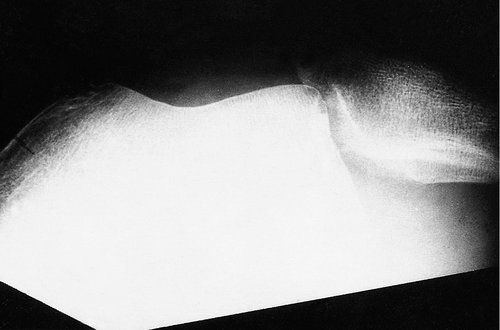

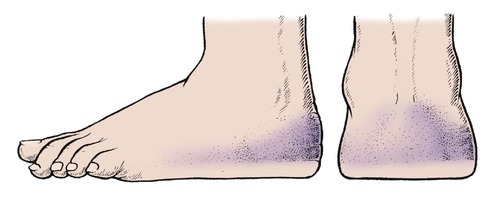

Fractures of the calcaneum

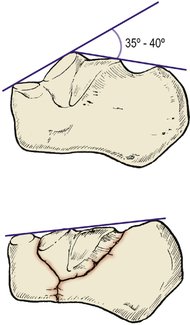

The calcaneum is broken by a blow to the heel, most often caused by landing from a height. Because the calcaneum is made of cancellous bone, it is crushed at the moment of impact and restoration of the anatomy is difficult (Fig. 14.58). If the cortical fragments are placed in their correct position, a cavity remains and must be filled with a bone graft.

|

| Fig. 14.58

Fracture of the calcaneum with loss of Bohler’s angle.

|

Recognition

Many different patterns of fracture occur, and many escape recognition in the accident department. To assess the calcaneum radiologically, look for three things:

1. Loss of ‘Bohler’s angle’ (Fig. 14.59).

|

| Fig. 14.59

Bohler’s angle.

|

2. Widening or disruption of the body on an axial view (Fig. 14.60).

|

| Fig. 14.60

Types of fracture of the calcaneum: (left) avulsion of posterior segment by the Achilles tendon; (middle) fracture of sustentaculum tali; (right) burst fracture with compression and loss of height.

|

3. Separation of the ‘beak’ at the back of the bone (see Fig. 14.58).

The fracture is very painful and stops the patient from putting the foot to the ground. After a day, bruising begins to appear in a horseshoe around the heel (Fig. 14.61). If this pattern of bruising is present and no fracture has been seen, look again at the radiographs.

|

| Fig. 14.61

Horseshoe bruise around the heel in the presence of a fracture of the calcaneum.

|

Complications

Undisplaced fractures of the calcaneum are unimportant but major fractures destroy the subtalar joint and cause stiffness of the subtalar and midtarsal joints. This leads to disabling pain when walking on rough surfaces. These symptoms go on improving for 2 years but seldom resolve completely.

Treatment

Treatment can be conservative or operative.

Conservative treatment consists of rest and protection from weight-bearing for 6 weeks or until the patient can bear weight on the foot in comfort.

Operative treatment consists of open reduction and bone grafting of the bony defect. Operation is most often advised for severe crushing injuries in young adults. The results are reasonable and perhaps better than the results of conservative management in severe injuries.

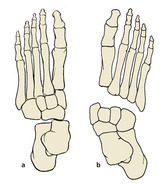

Fractures of the tarsus

The tarsal bones are hard, solid bones resistant to fracture but they have flat surfaces and dislocations or fracture dislocations occur at two points (Fig. 14.62): (1) the midtarsal joint and (2) the tarsometatarsal joint (Fig. 14.63).

|

| Fig. 14.62

(a) Midtarsal dislocation; (b) tarsometatarsal dislocation.

|

|

| Fig. 14.63

A tarsometatarsal dislocation.

|

The injuries are caused by apparently trivial twisting injuries of the forefoot and can easily escape detection both clinically and radiologically. These fractures are a pitfall for the unwary.

Treatment

If not correctly diagnosed and accurately reduced, the dislocation becomes permanent and a disabling deformity results. Open reduction and internal fixation is often needed.

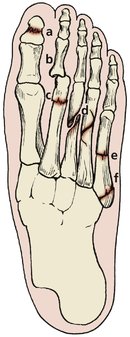

Fractures of the forefoot (Fig. 14.64)

Fifth metatarsal

The styloid process of the fifth metatarsal can be avulsed by trivial twisting injuries of the forefoot. Left untreated, the fracture usually joins soundly with bone or fibrous tissue and little long-term disability follows. The shaft may also be fractured (Fig. 14.65).

|

| Fig. 14.64

Fractures in the forefoot: (a) crush fracture of the phalanx; (b) dislocation of the metatarsophalangeal joint; (c) fatigue fracture; (d) spiral fracture of the metatarsals; (e) transverse fracture of the fifth metatarsal; (f) fracture of the styloid process of the fifth metatarsal.

|

|

| Fig. 14.65

(a), (b) Spiral fracture of the fifth metatarsal.

|

Treatment

There is considerable pain and tenderness of the fracture site immediately after the injury and a below-knee cast may be needed to relieve pain. Some patients can manage well with just a firm crêpe bandage.

Multiple spiral fractures

Twisting injuries of the forefoot may cause spiral fractures of several metatarsals, sometimes accompanied by dislocation of the tarsometatarsal joints (Fig. 14.66).

|

| Fig. 14.66

Transverse fractures of the second, third and fourth metatarsals with a spiral fracture of the neck of the third metatarsal.

|

Treatment

The normal relationship of the metatarsal heads must be restored so that the area of contact with the ground remains flat and excessive loading of any single metatarsal head is avoided. Immobilization of the fractures with percutaneous pins may be necessary.

Fractures of the phalanges

The phalanges are in a vulnerable position and easily broken by falling objects (Fig. 14.67). These fractures are common industrial injuries and can be avoided by wearing shoes with protective toecaps.

|

| Fig. 14.67

Crush fracture of the distal phalanx of the great toe.

|

Treatment

Crush injuries of the distal phalanges should be treated as severe soft tissue injuries without regard to bony continuity. The foot should be elevated until swelling has subsided and adequate pain relief has been given. Elevation for several days may be required.

Crushed foot

Crushing injuries of the foot, like crushing injuries of the hand, cause persistent stiffness.

Treatment

The foot should be elevated with the patient in bed until the swelling has settled. This may take 2 weeks. Walking can then be allowed, with a supporting bandage to reduce swelling.