INJURIES AND ILLNESSES DUE TO HEAT

HEAT ILLNESS (HYPERTHERMIA)

Conduction—heat exchange between two surfaces in direct contact. Lying uninsulated on hot (or cold) ground can result in significant heat exchange. The same is true for immersion into hot or cold water.

Convection—heat transferred from a surface to a gas or liquid, commonly air or water. When air temperature exceeds skin temperature, heat is gained by the body. Loose-fitting clothing allows air movement and assists conductive heat loss.

Radiation—heat transfer between the body and the environment by electromagnetic waves. Clothing protects the body from radiant heat, and the skin radiates heat away from the body. Highly pigmented skin absorbs more heat than nonpigmented skin.

Evaporation—consumption of heat energy as liquid is converted to a gas. Evaporation of sweat is an effective cooling mechanism.

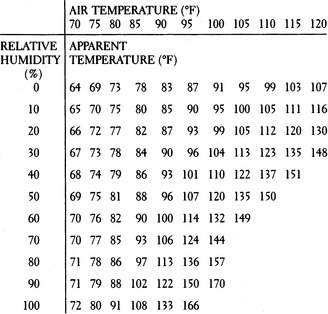

In the normal situation, the skin is the largest heat-wasting organ, and radiates approximately 65% of the daily heat loss. The skin is also largely responsible for evaporation (of sweat). Extreme humidity impedes evaporation and greatly diminishes human temperature control. The National Weather Service heat index (Figure 178) roughly correlates air temperature and relative humidity to derive an “apparent temperature.” At all temperatures, humidity makes the situation worse. For instance, at an air temperature of 85°F, if the relative humidity is 80%, the apparent temperature is 97°F.

| Apparent Temperature Range | Dangers/Precautions at This Range |

|---|---|

| 80°F–90°F (27°C–32°C) | Exercise can be difficult; enforce rest and hydration |

| 90°F–105°F (32°C–41°C) | Heat cramps and exhaustion; be extremely cautious |

| 105°F–130°F (41°C–54°C) | Anticipate heat exhaustion; strictly limit activities |

| 130°F and above (54°C and above) | Setting for heatstroke; seek cool shelter |

When maximally effective, the complete evaporation of 1 quart (liter) of sweat from the skin removes 600 kilocalories of heat (equivalent to the total heat produced with strenuous exercise in 1 hour). Sweat that drips from the skin without evaporating does not contribute to the cooling process, but may contribute to dehydration. World-class distance runners who are acclimated to the heat can sweat in excess of 3½ quarts per hour. Since the maximum rate of gastric emptying (a surrogate for fluid absorption) is only 1.2 quarts per hour, it is easy to see how a person can become dehydrated. Thus, a person should be able to tolerate a 1 quart per hour sweat rate and manage rehydration with oral fluids. The scalp, face, and torso are most important in terms of sweating.

HEAT EXHAUSTION AND HEATSTROKE

The signs and symptoms of heatstroke are extreme confusion, weakness, dizziness, unconsciousness, low blood pressure or shock (see page 60), seizures, increased bleeding (bruising, vomiting blood, bloody urine), diarrhea, vomiting, shortness of breath, red skin rash (particularly over the chest, abdomen, and back), darkened (“machine oil”) urine, and major core body temperature elevation (up to 115.7°F, or 46.5°C, has been reported in a heatstroke survivor). Again, it is important to note that sweating may be present or absent. At the time of collapse, most victims of heatstroke are still sweating copiously. It is rare for someone to feel cool externally when his temperature exceeds 105°F (45°C), but it is not impossible.

The most important aspect of therapy is to lower the temperature as quickly as possible. The body may lose its ability to control its own temperature at 106°F (41.1°C), so from that point upward, temperature can skyrocket. Manage the airway (see page 22) and administer oxygen (see page 431) at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute by facemask. Do not give liquids by mouth unless the victim is awake and capable of purposeful swallowing. Cooled liquids do not assist the cooling process enough to risk choking the uncooperative or confused victim.

Cooling the Victim

1. Remove the victim from obvious sources of heat. Shield him from direct sunlight and remove his clothing. Stop him from exercising.

2. The most efficient method of cooling is to drench the victim with large quantities of crushed ice and water, accompanied by vigorous massage. If you have a limited amount of ice, place ice packs in the armpits, behind the neck, and in the groin. There are safety issues to consider with total body immersion in cold water to treat hyperthermia, including access to the victim and even the risk for near-drowning. However, in a life-threatening field situation, if the only method available for cooling is immersion in a cold mountain stream, do it! Be alert for the need to remove the victim from the water to accomplish resuscitative measures (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]). Never leave the victim unattended.

3. If ice is not available, wet down the victim and begin to fan him vigorously. Evaporation is a very efficient method of heat removal. Use cool or tepid water; do not sponge the victim with alcohol. If electric fans are available, use them. Do not be concerned with shivering, so long as you continue to aggressively cool the victim.

4. There is a device on the market (CORECONTROL) for athletes that increases circulation through the hand to allow a cooling mechanism to have its effect on this area of brisk heat transfer.

5. Recheck the temperature every 5 to 10 minutes, to avoid cooling much below 98.6°F (37°C). When you have cooled the victim to 99.5°F to 100°F (37.5°C to 37.8°C), taper the cooling effort. After the victim is cooled, recheck his temperature every 30 minutes for 3 to 4 hours, because there will often be a rebound temperature rise.

6. Do not use aspirin or acetaminophen unless the victim has an infection. These specific drugs are used to combat fever that is caused by the release of chemical compounds from infectious agents into the bloodstream. Such compounds affect the portion of the brain (hypothalamus) that serves as the body’s thermostat, causing body temperature to rise. Aspirin or acetaminophen acts to block this chemical interaction in the brain, and thus eliminates the fever. If elevated body temperature is not caused by an infection, aspirin or acetaminophen will not work—and may in fact be harmful, leading to bleeding disorders or liver inflammation, respectively.

7. If the victim is alert, begin to correct dehydration (see page 208) using oral rehydration. Be certain that the concentration of carbohydrates or sugar in the beverage does not exceed 6%, so as not to inhibit intestinal absorption. Try to get 1 to 2 quarts (liters) into the victim over the first few hours. For every pound (0.45 kg) of weight loss attributed to sweating, have the victim ingest a pint (473 mL or 2 cups) of fluid. This may take up to 36 hours.

MUSCLE CRAMPS

Muscle cramps in a warm environment accompany overuse (see page 284) or water and salt losses in the individual who exerts strenuously. A well-trained athlete can lose 2 to 3 quarts (liters) of sweat per hour (a potential 20 g sodium loss each day). In most cases, cramps are caused by replacement of water without adequate salt intake. Heat per se doesn’t actually cause the cramps.

Treatment for cramps consists of gentle motion, massage, and stretching of the affected muscles, accompanied by fluid and salt replacement. This can be done by drinking water and balanced salt solutions or sports beverages before and during heavy exertion. One recommendation is to drink a solution that contains 3.5 g of sodium chloride and 1.5 g of potassium chloride in a quart (liter) of water. As a rough measure, ¼ to ½ tsp (1.3 to 2.5 mL) of table salt in water will suffice. With proper fluid and electrolyte replacement, salt tablets (which irritate the lining of the stomach) are usually unnecessary.

FAINTING

Fainting has many causes (see page 165). Fainting due to heat exposure occurs when a person (particularly an elder) adapts by dilating blood vessels in the skin and superficial muscles to deliver warm blood to the surface of the body, where the excess heat energy can be delivered back to the environment. The expansion of the superficial blood vessels allows a greater-than-normal proportion of the circulating blood volume to be away from the central circulation, which supplies, among other organs, the brain. This lack of sufficient central pressure is worsened when a person is on his feet for a prolonged period of time, because gravity allows a significant blood volume to pool in his lower limbs. Combined with fatigue and mild dehydration, the diversion of blood leads to a fainting episode, because not enough blood (with oxygen and glucose) is pumped to the brain. Dehydration can also stimulate the vagus nerve, which causes the heart rate to slow (“vasovagal” episode). A person with anemia, fever, low blood sugar, or acute injury may be particularly prone to fainting. Other risk factors for fainting due to vagal stimulation include prolonged standing, vigorous exercise in a warm environment, fear, emotional distress, and severe pain.

A victim who has suffered a fainting episode in the heat should be examined for any head or neck injuries, as well as other possible breaks or cuts. Other causes of fainting (low blood sugar, abnormal heart rhythm, and so on) must be considered. If fainting is due to the heat, the victim will reawaken shortly, because assuming a horizontal position returns blood to the brain and solves the major problem. In general, body temperature is not elevated.

AVOIDING HEAT ILLNESS

1. Avoid dehydration. Drink 1 pint (473 mL) of liquid 10 to 15 minutes before beginning vigorous exercise. Drink at least 1 pint to 1 quart (½ to 1 liter) of liquid with adequate electrolyte supplementation (see below) each hour during heavy exercise with sweating in a hot climate. Adequate water ingested during exercise is not harmful, does not cause cramps, and will prevent a large percentage of cases of heat illness. Encourage rest and fluid breaks. The temperature of the fluid ingested should be cool, to encourage it to empty from the stomach. It is a myth that ingesting cold fluid causes abdominal cramps, so long as the amount ingested is prudent.

2. Be watchful of the very young and very old. Their bodies do not regulate body temperature well and can rapidly become too hot or too cold. Do not bundle up infants in warm weather.

3. Stay in shape. Obesity, lack of conditioning, insufficient rest, and ingestion of alcohol and/or illicit drugs all contribute to an increased risk for heat illness. The herb ephedra contains ephedrine, which is reputed to enhance athletic performance; however, it increases metabolic rate and has caused many cases of heat illness and deaths.

4. Condition yourself for the environment. Gradual increased exposure to work in a hot environment for a minimum of an hour a day for 8 to 10 days will allow an adult to acclimatize. Children require 10 to 14 days. More time spent in the heat hastens the process. Acclimatization is manifested as increased sweat volume with a decreased electrolyte concentration (more efficient sweating), greater peripheral blood vessel dilatation (more efficient heat loss), lowered heart rate, decreased skin and rectal temperatures during exercise, increased water and salt conservation by the kidneys, and enhanced metabolism of energy supplies. Eat potassium-rich vegetables and fruits, such as broccoli and bananas. Do not restrict fluid intake during acclimatization. On the contrary, it is necessary to increase fluid intake to accompany increased sweat volume.

5. Wear clothing appropriate for the environment. Dress in layers so that you can add or shed clothing as necessary. Clothing should be lightweight and absorbent. Wear a loose-fitting broad-brimmed hat to shield yourself from the sun, but do not wear a hat if you do not need protection from the sun. Do not wear plastic or rubber sweat suits in the heat.

6. Towel off your face and scalp frequently, because 50% of sweating occurs from these areas. Remove headgear when possible to allow evaporation from the head. Allow the scalp, face, and upper torso access to air circulation, since these are the major areas of sweating and therefore provide opportunity for sweat evaporation.

7. Keep out of the sun on a hot day. Resting on hot ground increases heat stress; the sun can heat the ground by more than 40°F (22.2°C) above the air temperature. If you must lie on the ground, dig a shallow (a few inches, or centimeters) trench to get down to a cooler surface.

8. Avoid taking drugs that inhibit the sweating process (such as atropine, antispasmodics, anti–motion-sickness), diminish cardiac output (beta blockers), disrupt certain features of physiological activity (antidepressants, antihistamines), increase muscle activity (hallucinogens, cocaine), or promote dehydration (diuretics).

9. To find water in the desert, look for green plants. Near the ocean shore, drinkable water may be found below a sandy or gravel surface at an elevation above seawater. Look for green plants. Water may be found at the foot of cliffs that have become waterfalls after a rainstorm or flood. Look under rocks, even if the surface appears dry.

10. If you are prone to fainting episodes, particularly of the vasovagal type, learn to recognize the warning symptoms that occur before fainting, which include weakness, feeling light-headed, sweating, blurred vision, nausea, headache, warm or cold feeling, yawning, nervousness, and growing pale. You may also feel “out of body” or disoriented. If any of these occur and you recognize that you might faint, immediately try to lie face down on the ground, so that you do not fall, and allow gravity to assist in bringing blood from your limbs back to the central circulation and your brain.