INJURIES AND ILLNESSES DUE TO COLD

HYPOTHERMIA (LOWERED BODY TEMPERATURE)

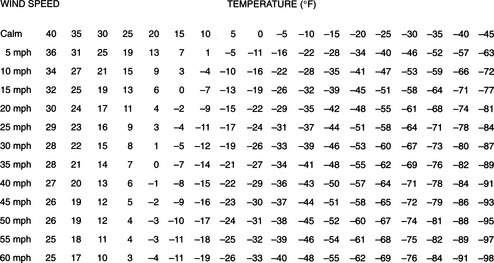

Heat is lost from the body to the environment by direct contact (conduction), air movement (convection), infrared energy emission (radiation), the conversion of liquid (sweat) to a gas (evaporation), and the exhalation of heated air from the lungs (respiration). It is important to note that the rate of heat loss via conduction is increased 5-fold in wet clothes and at least 25-fold in cold-water immersion. Windchill (Figure 176) refers to the increase in the rate of heat loss (convection) that would occur when a victim is exposed to moving air. This chill can be compounded further if the victim is wet (conduction, convection, and evaporation).

Immersion hypothermia refers to the particular case in which a victim has become hypothermic because of sudden immersion into cold water. Again, water has a thermal conductivity approximately 25 times greater than air, and a person immersed in cold water rapidly transfers heat from his skin into the water. The actual rate of core temperature drop in a human is determined in part by these phenomena and in part by how quickly heat is transferred from the core to the skin, skin thickness, the presence or absence of clothing, the initial core temperature, gender, fitness, water temperature, drug effects, nutritional status, and behavior in the water.

A sudden plunge into cold water causes the victim to hyperventilate (see page 300), which may lead to confusion, muscle spasm, and loss of consciousness. The cold water rapidly cools muscles and the victim loses the ability to swim or tread water. Muscles and nerves may become ineffective within 10 minutes. Over the ensuing hour, shivering occurs and then ceases. Anyone pulled from cold water should be presumed to be hypothermic. In terms of survival, the aphorism is that when a person is plunged into very cold water (32°F or 0°C), he or she has 1 minute to control breathing (e.g., to stop hyperventilating from the “gasp reflex”), 10 minutes of purposeful movement before the muscles are numb and not responsive, 1 hour before hypothermia leads to unconsciousness, and 2 hours until profound hypothermia causes death.

91.4°F to 98.6°F (33°C to 37°C). Sensation of cold; shivering; increased heart rate; urge to urinate; slight incoordination in hand movements; increased respiratory rate; increased reflexes (leg jerk when the knee is tapped); red face; muscular incoordination, stumbling gait, maladaptive behavior, rapid heart rate converting to slow heart rate, apathy.

85.2°F to 91.4°F (29°C to 33°C). Stupor; decreased or absent shivering; weakness; apathy, drowsiness, and/or confusion; poor judgment; slurred speech; inability to walk or follow commands; paradoxical undressing (inappropriate behavior); complaints of loss of vision; amnesia; rapid heart rate converting to slow heart rate; rapid breathing rate converting to shallow breathing; loss of shivering; possible nonreactive or dilated pupils, abnormal heart rhythms, diminished breathing.

71.6°F to 85.2°F (22°C to 29°C). Minimal breathing; coma; decreased respiratory rate; decreased neurologic reflexes progressing to no reflexes; no voluntary motion or response to pain; very slow heart rate, low blood pressure; maximum risk for ventricular fibrillation. The victim no longer can control his body temperature and rapidly cools to the surrounding environmental temperature.

Below 71.6°F (22°C). Rigid muscles; barely detectable or absent blood pressure, heart rate, and respirations; dilated pupils; risk for ventricular fibrillation; appearance of death.

Unless the victim has suffered a full cardiopulmonary arrest, the hypothermia itself may not be harmful. Unless tissue is actually frozen, cold is in many ways protective to the brain and heart. However, if a hypothermic victim is improperly transported or rewarmed, the process may precipitate ventricular fibrillation, in which the heart does not contract, but quivers in such a fashion as to be unable to pump blood. The burden of rescue is to transport and rewarm the victim in a way that does not precipitate ventricular fibrillation.

The following general rules of therapy apply to all cases:

1. Handle all victims gently. Rough handling can cause the heart to fibrillate (cause a cardiac arrest). Secure the scene and avoid creating additional victims via unstable snow, ice, or rock fall.

2. If necessary, protect the airway (see page 22) and cervical spine (see page 37). Stabilize all other major injuries, such as broken bones.

3. Prevent the victim from becoming any colder. Provide a shelter. Remove all his wet clothing and replace it with dry clothing. Don’t give away all of your clothing, however, or you may become hypothermic. Replace wet clothing with sleeping bags, insulated pads, bubble wrap, blankets, or even newspaper. The “blizzard pack” from Blizzard Protection Systems, Ltd. (www.blizzardpack.com) can be used to provide protection from the elements. The Pro-Tech Extreme bag or vest, SPACE brand emergency bag, SPACE brand all-weather blanket, and SPACE brand emergency blanket, all from MPI Outdoors (www.mpioutdoors.com), are other options for this purpose.

4. Do not attempt to warm the victim by vigorous exercise, rubbing the arms and legs, or immersing in warm water. This is “rough handling” and can cause the heart to fibrillate if the victim is severely hypothermic.

Mild Hypothermia

Prevent the victim from becoming any colder. Get him out of the wind and into a shelter. If necessary, build a fire or ignite a stove for added warmth. Gently remove wet items of clothing and replace them with dry garments. This is very important, even if the victim will be very briefly exposed out in the open. If no dry replacements are available, the clothed victim should be covered with a waterproof tarp or poncho to prevent evaporative heat loss. Cover the head, neck, hands, and feet. Insulate the victim above and below with blankets. If the victim is coherent and can swallow without difficulty, encourage the ingestion of warm sweetened fluids. Good choices include warm gelatin (Jell-O), juice, or cocoa, because carbohydrates fuel shivering. If only cool or cold liquids are available for drinking, this is fine. Avoid heavily caffeinated beverages. If a dry sleeping bag is available, one or more rescuers should climb in with the victim and share body heat. However, this technique may not be very effective, and great care must be taken not to cause the victim to become wet (e.g., from the rescuer’s sweat). Do not apply commercial heat packs, hot-water-filled canteens, or hot rocks directly to the skin; they must be wrapped in blankets or towels to avoid serious burns. Try to keep the victim in a horizontal position until he is well hydrated. Do not vigorously massage the arms and legs, because skin rubbing suppresses shivering, dilates the skin, and does not contribute to rewarming.

Severe Hypothermia

Examine the victim carefully and gently for signs of life. Listen closely near the nose and mouth and examine chest movement for spontaneous breathing. Feel at the groin (femoral artery) and neck (carotid artery) for a weak and/or slow pulse (see page 33).

If the victim shows any signs of life (movement, pulse, respirations), do not initiate the chest compressions of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). If the victim is breathing regularly, even at a subnormal rate, his heart is beating. Because hypothermia is protective, the victim does not require a “normal” heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. Pumping on the chest unnecessarily is “rough handling,” and may induce ventricular fibrillation. Administer supplemental oxygen (see page 431) by facemask if it is available.

If the victim is breathing at a rate of less than 6 to 7 breaths per minute, you should begin mouth-to-mouth breathing (see page 29) to achieve an overall rate of 12 to 13 breaths per minute.

If help is on the way (within 2 hours) and there are no signs of life whatsoever, or if you are in doubt (about whether the victim is hypothermic, for instance), you should begin standard CPR (see page 32). If possible, continue CPR until the victim reaches the hospital. Rescue breathing should take priority over chest compressions, particularly in the victim of cold-water immersion. There have been documented cases of “miraculous” recoveries from complete cardiopulmonary arrest associated with environmental hypothermia after prolonged resuscitation, presumably because of the protective effect of the cold. Remember, “no one is dead until he is warm and dead.” However, all of these victims were ultimately resurrected in the hospital, after they had been fully rewarmed.

Preparing a Hypothermic Victim for Transport

1. Keep the victim dry. Replace all wet clothing. If there is no replacement clothing available, wring out the wet clothing, including gloves and mittens, and then put it back on the victim. Lay the victim on a sleeping bag and then cover him with a layer of blankets. If necessary, use bubble wrap or some other insulating material. If the hands are extremely cold, pull them out of the sleeves of clothing in order to put the hands in the victim’s armpits for warming. See above for emergency waterproof blankets and bags. Cover everything with a plastic sheet.

2. Keep the victim horizontal. Do not allow massage of the extremities. Do not allow the victim to exert himself.

3. Splint and bandage all injuries as appropriate. Cover all open wounds.

4. Limit rewarming to methods that prevent further heat loss. Place insulated (e.g., with clothing) hot-water bottles in the victim’s armpits and groin. Keep his head and neck covered.

Prevention of Hypothermia

1. Carry adequate food and thermal wear, such as Thermax, Capilene, and/or polypropylene (“polypro”) or wool undergarments. Anticipate the worst possible weather conditions. Dress in layers so that you can adjust clothing for overcooling, overheating, perspiration, and external moisture. Use a foundation layer to wick moisture from the body to outer layers. The first layer (such as CoolMax) should keep the skin cool and dry (to avoid perspiration). Add an insulation layer to provide incremental warmth. For shirts, use wool, fleece, Capilene, or polypropylene. Consider a turtleneck or neck gaiter. For pants, wear wool or pile, with a fly. Carry windproof and waterproof outer garments, mittens or gloves (with glove liners), socks, and a hat. In very cold weather, up to 70% of generated heat may be lost by radiation from the uncovered head. Boots should be large enough to accommodate a pair of polypropylene socks (“liner socks”) plus at least one pair of heavy wool socks without cramping the toes.

3. Keep hands and feet dry. This is important to avoid frostbite as well. Hand Sense is a cream that can be applied to the hands to keep them dry by reducing perspiration. It was designed as a topical protectant, and is not a moisturizer. For the feet, aluminum chlorohydrate–containing antiperspirant sprayed onto the skin can help control sweating. Do this three times a week for the first week of winter, then once a week after that. Avoid leather boots that become soaked with moisture and do not dry out easily.

4. Do not exhaust yourself in cold weather. Do not sit down in the snow or on the ice without insulation beneath you.

5. Seek shelter in times of extreme cold and high winds. Don’t sit on cold rocks or metal. Insulate yourself from the ground with a pad, backpack, log, or tree limb. Carry a properly rated (for the cold) sleeping bag stuffed with Hollofil II, Quallofil, or down. Insulate hands and feet well, even when you are in your sleeping bag, which should be fluffed up before entry. Do not enter a sleeping bag if you are wet without drying off first if possible.

6. Do not become dehydrated. In the cold, dehydration is caused by evaporation from the respiratory tree, increased urination, and inadequate fluid intake. Drink at least 3 to 4 quarts (liters) of fluid daily. During extreme exercise, drink at least 5 to 6 quarts per day. Ingesting snow is an inefficient way to replace water, because it worsens hypothermia. Drink cold water from a stream in preference to eating snow. Do not skip meals. Do not consume alcoholic beverages in cold weather. They cause an initial sensation of warmth because of dilation of superficial skin blood vessels, but this same effect contributes markedly to heat loss. At night, fill a canteen or Nalgene water container with at least 1 quart (liter) of water, and sleep with it to keep it from freezing.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU FALL THROUGH THE ICE

1. When a person falls into extremely cold water, he begins to gasp and hyperventilate. Control your breathing. Calm down and slow your breathing rate, so that you are not hyperventilating. This generally takes 30 seconds to 2 minutes.

2. Keep your hands and arms on top of the ice and kick your feet vigorously, to bring your body to a horizontal position and propel you up onto the ice. Otherwise, keep swimming at a minimum. Keep clothing on in the water—it contributes to insulation and helps with flotation. If you are able to slide your body out of the water onto the ice, do not stand up. Roll or slide your body away from the opening onto thicker ice, where you may now stand. Try to leave in the direction from which you first approached, as this ice has already proven that it can withstand your weight. If you cannot exit the water, try to hold your arms on top of the ice, so that they freeze to the ice, which will prevent you from submerging under the surface of the water. This may give you an extra hour of survival time.

HOW TO ASSIST SOMEONE WHO HAS FALLEN THROUGH THE ICE

1. Recognize that ice conditions are unsafe. No one else should approach the area.

2. Resist the urge to rush up to help the victim, so that you don’t also fall through the ice. Encourage the victim to remain calm and not panic. Direct the victim to an area of strong ice and to attempt a self rescue, as described above.

3. If self rescue is not accomplished, you can throw a buoyant object to the victim to help him remain floating. Before it is thrown, tie a rope or cord to the object, so that if the victim can hold onto it, you might be able to pull the victim. If only a rope is available, tie a large loop at the end, which the victim can grab. Instruct the victim to put the loop over the body and under the arms, put one arm through the loop and bend his elbow around the rope, or just hold on.

4. The victim might be reached with a long tree branch, ladder, or other object that can be pushed along the surface of the ice. It is important for the rescuer to not get too close to the hole in the ice.

5. If the victim cannot be removed from the water using the techniques above, he should be instructed to hold the arms up on the ice for the purpose of letting them freeze to the ice while help is summoned.

6. To avoid falling through ice in the first place, you should look for signage that might indicate its safety or unsafety; check with local authorities if they have any information; travel across ice under observation of someone else; bring safety equipment; wear a lifejacket or other flotation device; avoid traveling on ice at night; select “blue ice” over white ice or gray ice; and avoid ice with cracks or slushy areas.

WINTER STORM PREPAREDNESS

Winter storm preparedness is essential for anyone who drives a motor vehicle in snow country. One must always be aware of the possibility of spending an unplanned night out in a vehicle. Causes include bad weather, breakdown, having an accident, running out of fuel, becoming lost, and getting stuck. Winter driving is especially hazardous because of the dangers of driving on snow or ice, losing visibility and orientation, fewer people on the road from whom to receive assistance, and the threats of frostbite and hypothermia. Accepting the possibility of trouble, carrying a vehicle survival kit (see below), and giving some thought to survival strategies will help prevent a night out in your car from deteriorating into a life-threatening experience.

Foresight enough to include heavy clothing and blankets or sleeping bags in the cold-weather vehicle survival kit is better than relying excessively on external heat generation. Do not smoke tobacco products or drink alcohol. If you have to exit the vehicle in a snowstorm, put on additional windproof clothing and snow goggles, and tie a lifeline to yourself and the door handle before moving away from the vehicle.

A vehicle cold weather survival kit should include the following items:

1. Sleeping bag or two blankets for each occupant

2. Extra winter clothing, including gloves, boots, and snow goggles, for each occupant

6. Long-burning candles, at least two

8. Spare doses of personal medications

9. Swiss army knife or Leatherman-type multitool

10. Three 3 lb empty coffee cans with lids, for melting snow or sanitary purposes

12. Cell phone and/or citizen’s band radio, with chargers

13. Portable radio receiver, with spare batteries

14. Flashlight with extra batteries and bulb

15. Battery booster cables and/or car battery recharging unit (plugs into cigarette lighter)

16. Extra quart of automobile oil (place some in hubcap and burn for emergency smoke signal)

21. Windshield scraper and brush

23. Small sack of sand or cat litter

24. Two plastic gallon drinking water jugs, full

27. Flagging, such as surveyor’s tape (tie to top of radio antenna for signal)

29. Notebook and pencil/marker

30. Long rope (e.g., clothesline) to act as safety rope if you leave car in blizzard

FROSTBITE

During exposure, once the temperature of a hand or foot drops to 59°F (15°C), the blood vessels maximally constrict and minimal blood flow occurs. As the limb temperature declines to 50°F (10°C), there may be brief periods of blood vessel dilation, alternated with constriction, as the body attempts to provide some protection from the cold. This is known as the “hunting response” and is seen more commonly in the Inuit (Eskimos) and those of Nordic descent. Below 50°F (10°C), the skin becomes numb and injury may go unnoticed until it is too late. Tissue at the body surface freezes at or below a temperature of 24.8°F (−4°C) because of the effect of underlying warm tissue. Once circulation is abolished, the skin temperature may drop at a rate in excess of 1°F (0.56°C) per minute. Once tissue freezes, it cools rapidly to attain the temperature of the environment.

Once the victim has reached a location (shelter) where refreezing will not occur, remove all constrictive jewelry and wet clothing. Replace wet clothes with dry garments. Immerse the frostbitten part in water heated to 104°F to 108°F (40°C to 42.2°C). Do not induce a burn injury by using hotter water. You can estimate 108°F (42.2°C) water by considering it to be water in which normal skin can be submerged for a prolonged period with minimal discomfort. Heated tap water may be too hot. Never use a numb frostbitten finger or toe to test water temperature. It is best to use your own hand or the victim’s uninjured hand to test the temperature. Circulate the water to allow thawing to proceed as rapidly as possible. When adding more hot water, take the body part out, add the water, test the temperature, and then reimmerse the part. It is best to use a container in which the body part can be immersed without touching the sides; for instance, a 20-quart (20-liter) pot will accommodate a foot. If the skin is frozen to mittens or metal, use heated water to remove them. Never rewarm the tissues by vigorous rubbing or by using the heat of a campfire, camp stove, or car exhaust, because you most certainly will damage the tissues.

If the victim is hypothermic, attend first to the hypothermia. Thawing should not be undertaken until the core body temperature has reached 95°F (35°C) (see page 305).

First degree. Numbness, redness, and swelling; no tissue loss.

Second degree. Superficial blistering, with clear (yellowish) or milky fluid in the blisters, surrounded by redness and swelling. There is little, if any, tissue loss.

Third degree. Deep blistering, with purple blood-containing fluid in the blisters. There is usually tissue loss.

Fourth degree. Extremely deep involvement (including bone); induces mummification. There is always tissue loss.

Sensation may remain until blisters appear at 6 to 24 hours after rapid rewarming. These often do not extend to the ends of fingers and toes (Figure 177). Leave these blisters intact. After thawing the skin, protect it with fluffy, sterile bandages (aloe vera lotion, gel, or cream should be applied, if available). Pad gently between the digits with sterile cotton or wool pads, held in place by a loose, rolled bandage. Transport the victim to a medical facility. Administer ibuprofen 400 mg or aspirin 325 mg twice a day. If frostbite involves the feet, try to minimize walking. Do not allow tobacco use or the drinking of alcohol. Keep the victim well hydrated with warm beverages. Administer pain medications as needed.

After the thaw, if the victim is days away from hospital care, manage the wound as follows:

1. If you don’t have sufficient sterile bandages to redress the wounds at least once a day until you reach a hospital, allow blisters to remain intact. Apply topical aloe vera gel or lotion twice a day. Cover with sterile gauze.

2. If white or clear blisters begin to leak, trim them away and apply antiseptic ointment (mupirocin or bacitracin) or cream (mupirocin). If antiseptic ointment is not available, continue with aloe vera gel or lotion. Cover with a sterile dressing (see page 276), taking particular care to pad with cotton or gauze between fingers and toes.

3. If at all possible, keep purple or bloody blisters intact, because they provide a covering that keeps the underlying damaged tissue from drying out. Apply topical aloe vera gel or lotion twice a day. Cover with sterile gauze.

5. Apply a protective splint (see page 74) if necessary to surround the bulky cushion dressing.

6. For the first 72 hours after the injury, administer dicloxacillin, cephalexin, or erythromycin.

7. If the skin blackens and begins to harden, apply topical mupirocin or bacitracin ointment, or mupirocin cream, daily to the margin where the dying skin meets the normal skin.

Tissue that has been destroyed by frostbite will usually harden and turn black in the second week after rewarming, forming a “shell” over the viable tissue underneath. If the destruction is extensive, the affected area will wither and shrivel beneath the blackness, and self-amputate over 3 to 6 months. If the victim cannot seek medical care in that interval, the wound should be kept clean and dry, and signs of infection (see page 240) treated appropriately with antibiotics.

The corneas can be frostbitten if people (such as snowmobilers) force their eyes open in situations of high windchill. Symptoms include blurred vision, aversion to light, swollen eyelids, and excessive tearing. The treatment is the same as for a corneal abrasion (see page 180).

Prevention of Frostbite

1. Dress to maintain body warmth. Wear adequate, properly fitting (not tight) clothing, particularly boots that can accommodate a pair of polypropylene socks and at least one pair of wool socks without cramping the toes or wrinkling the socks. Dress your feet for the temperature of subsurface colder snow, not the “warm” snow at the surface. Take care to cover the head, neck, hands, feet, and face (particularly the nose and ears). Wear mittens in preference to gloves, to decrease the surface area available for heat loss from the fingers. Mitten shells and gloves should be made of synthetics or soft, flexible, dry-tanned leather (e.g., moose, deer, elk, caribou) that won’t dry stiffly after it becomes wet. Do not grease the leather. Mitten inserts and glove linings should be made of soft wool. Tie mittens and gloves to sleeves or string them around the neck, so they are not dropped or lost. Carry pocket, hand, and/or foot warmers and use them properly. Choices include fuel-burning warmers or chemical (such as Grabber hand warmer) packs, reusable sodium acetate thermal packs, or air-activated, single-use hand and pocket warmers.

2. Keep clothing dry. Avoid perspiring during extremely cold weather. Keep skin dry and avoid moisturization.

3. Do not touch bare metal with bare skin. Certain liquids (such as gasoline) become colder than frozen water before they freeze, and can cause frostbite. Cover all metal handles with cloth, tape, or leather. Take care when handling cameras. For brief periods of exposure when dexterity is required, wear silk or rayon gloves.

4. Do not maintain one position in the cold for a prolonged period of time. Avoid cramped quarters.

5. Wear a sunscreen with a cream or grease base to prevent windburn.

6. Stay well hydrated. Eat enough food to maximize body-heat production. Avoid becoming fatigued.

7. Do not overwash exposed skin in freezing weather. The natural oils are a barrier to cold injury. Shave sparingly or not at all for cosmetic reasons. If skin becomes exceedingly dry, apply a thin layer of petrolatum-based ointment.

8. Do not drink alcohol or use tobacco products.

IMMERSION FOOT (TRENCH FOOT)

If you suspect immersion foot, carefully cleanse and dry the limb, and rewarm it. After the limb has initially been fully rewarmed, it may become very reddened, warm to the touch, swollen, and painful. Then, maintain it in an environment where the victim can be kept warm while the injured limb(s) can be kept cool (not cold). Do not rub the limb. Pain reaches its maximum intensity in 24 to 36 hours, and may be worsened at night. If the limbs are held in a dependent position, they may turn purplish in color; when raised, they may blanch. Treat the injury as a combination of frostbite and a burn wound, using daily dressing changes, topical antiseptic ointments, and antibiotics if necessary to treat any infection. If left unattended, immersion foot can lead to prolonged disability. In a severe case, the skin may become gangrenous.

RAYNAUD’S PHENOMENON

Raynaud’s phenomenon is constriction of tiny blood vessels in the fingers and/or toes after exposure to cold or an emotionally stressful situation. The initial appearance is one of severely blanched (whitened) or bluish skin, often with a sharp “cut-off” margin in the midportion of the digit(s). This is caused by decreased circulation. The episode ends with vigorous reflow of blood into the digit, which causes it to become warm and reddened. This phenomenon is different and much more pronounced than the normal mottling or diffuse and persistent discoloration sometimes seen in hands and feet exposed to cold. Raynaud’s phenomenon is usually symmetrical, involving both hands or both feet, and is usually apparent in sufferers by age 40 years. Because Raynaud’s phenomenon can be associated with a number of underlying diseases or anatomic abnormalities, a first-time sufferer should seek medical evaluation. Prevention in the outdoors involves primarily protecting the hands and feet and keeping them warm, avoiding drugs that cause blood vessel constriction, and prohibiting tobacco use. Many drugs have been recommended at one time or another to treat Raynaud’s phenomenon, but at the current time the calcium-channel blockers (such as nifedipine) and drugs that block the sympathetic nervous system (which causes blood vessels to constrict) are most in favor as therapies for use outside of the hospital. Blood vessel dilators, such as nitroglycerin or niacin, have not been proven effective.