Chapter 27 Injection snoreplasty*

1 INTRODUCTION

There is a vast array of choices available to the otolaryngologist to treat simple snoring. The majority of these procedures function via the principle of palatal stiffening in which the vibrating floppy soft palate of the snoring patient is stiffened by creating scar tissue in or on the palate. Injection snoreplasty (IS) was originally developed as a modification of a solitary, indistinct case series published in the 1940s in which fish oil was injected into the pharynx of three patients to ‘alter the “flutter ratio” of these tissues as to reduce or eliminate snoring.’1 IS serves well as an alternative to the currently available snoring treatments that are either painful and/or expensive.2 IS is highly effective in the majority of patients, is easily performed in the office with inexpensive materials, and typically results in mild pain only that does not prevent the patient from returning to the majority of their daily activities.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

IS is most effective in patients who suffer from socially bothersome palatal flutter snoring. IS has not been found to be effective in managing obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) (author’s unpublished data) and therefore, it is strongly recommended that OSAS be objectively excluded prior to snoring treatment. This is best accomplished with polysomnography as the history and physical exam are limited in their accuracy in diagnosing and excluding OSAS.3

IS (and most currently available snoring treatments) targets only the soft palate for snoring treatment. Fortunately, it appears the majority (estimated to be approximately 85%) of snoring patients suffer from palatal flutter snoring.4 Ascertaining that the patient does indeed suffer from palatal flutter snoring, as opposed to other sites of snoring noise production, can translate to increased success with IS and other palatal snoring procedures.5 Commercially available ‘take-home’ polysomnographic technology does exist that appears to reliably identify palatal flutter snoring that translates into improved treatment success rates. However, one must be careful in relying on objective snoring analysis to the point where the ultimate goal of improving the patient’s subjective, social problem of snoring is overlooked.

3 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROCEDURE

IS can be easily accomplished in a typical 20-minute office visit.2 Informed consent is first obtained in all cases. Topical anesthesia is obtained with a thorough application of benzocaine spray or gel. This will also help the majority of patients with a problematic gag reflex. Local injected anesthesia (1% or 2% lidocaine without epinephrine) can be used to further anesthetize the soft palate, but is not necessary as the procedure can be quickly accomplished with a brief, mildly uncomfortable single injection that would be analogous to a local anesthetic injection.

IS has been successfully performed with three different sclerosing agents. The authors have reported the safe and effective use of two different agents in large numbers of patients. Three percent sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) (30 mg/ml SotradecolTM, Bioniche Pharma, Lake Forest, Illinois, USA, http://www.sotradecolusa.com/) was used in the original developmental animal model and in the initial IS human use studies.6 Three percent STS has been used for over five decades for varicose vein therapy and has an excellent safety record. It is inexpensive (less than $30 per treatment at the time of writing), easily obtained, and requires no dilution or mixing. It is highly effective and is the agent of choice for us. It is important to note that STS has NOT been FDA approved for palatal sclerotherapy and its use as such entails ‘off label’ use. It is unlikely that an FDA approval trial will ever be performed due to the fact that STS is no longer under patent protection.

IS has also been extensively performed by the authors with a 50–50 combination of 2% lidocaine (no epinephrine) and 98% dehydrated ethanol (sterile for injection). The safety and efficacy of dehydrated alcohol were demonstrated in an animal and human use study.7 Ethanol was chosen as an alternative to STS given its equally excellent long-term safety record, its widespread availability, and its low cost (less than $20 per at the time of writing). There does not appear to be any significant difference in the effectiveness and discomfort level in STS and ethanol.7 Again it is noted that ethanol is also not FDA approved for palatal sclerotherapy and will likely never undergo an approval trial for the same reasons as STS.

IS has also been successfully performed by published report using a lesser known sclerosing agent called Aethoxysklerol (AES).8 The authors have not used this agent and refer the interested reader to the original article for more information.

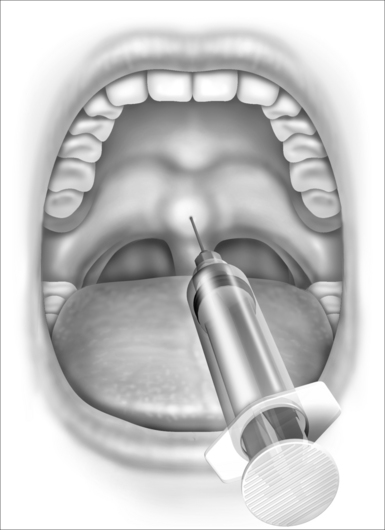

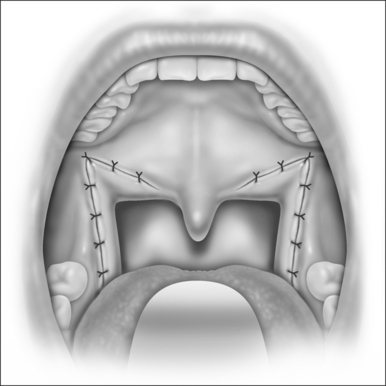

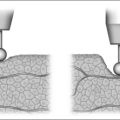

After topical anesthesia is obtained and the sclerosing agent is selected, the procedure is simply accomplished with a single midline soft palate injection. Typically a 2 ml syringe and a 27-gauge inch and a half needle are used and 1.5–2.0 ml of sclerosing agent is injected. The location of the injection is important to the success of the procedure and in minimizing patient discomfort (Fig. 27.1). The injection is best placed in the midline soft palate approximately 1cm proximal to the edge of the soft palate near the hard palate junction. It should NOT be placed into the uvula as this will produce significant uvular swelling that is often distressing to the patient. The injection is placed submucosally and NOT deep to the palatal muscle. The goal of the injection is to create a superficial sloughing of the soft palate mucosa that will be replaced by scar tissue, thereby stiffening the palate and reducing the patient’s snoring.

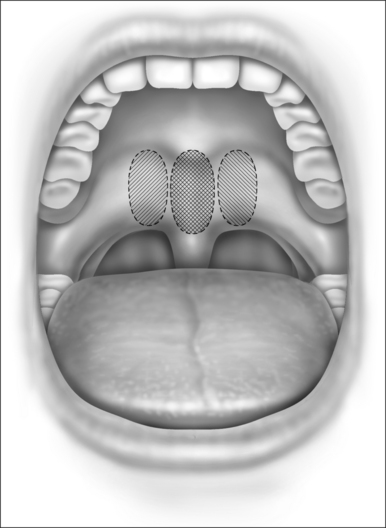

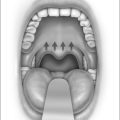

In rare cases, the initial injection will not be completely successful. In this case, a second injection can be performed. This is typically placed in two separate sites in the lateral edges of the previous injection to produce more widespread palatal stiffening (Fig. 27.2). The injection is again placed submucosally with approximately 1.0 ml placed in each site.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT ANDCOMPLICATIONS

All patients should be cautioned that palatal ulceration and sloughing will likely occur after IS. This should not be considered a complication as this tissue injury and the resulting replacement with scar tissue is the directed goal of the procedure. However, we have observed in rare cases (less than 1%) that a complete palatal fistula can occur.9 These case have all been managed conservatively with antibiotics and observation. All observed fistulae have closed spontaneously and no lasting velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) has ever been observed.

5 SUCCESS/FAILURE RATES

IS has been found to be successful short term in approximately 76.7% to 92% of patients.2,5,7,8,9 This result is most likely due to the fact that palatal snoring is the predominant form of snoring in approximately 85–90% of snorers.4 Therefore, it can be deduced that those patients who report no benefit from IS (or likely any other palatal snoring procedure) have a high probability of being non-palatal flutter snorers. If a patient reports no benefit from the procedure and scar tissue is visible and/or palpable on the soft palate after the procedure, then no further treatment is recommended. If no visible/palpable scar tissue is present (rare) then further treatment with IS or another palatal stiffening procedure can be attempted until scar tissue is produced and snoring is reassessed. If scar tissue is observed yet there has been a less than complete response to the treatment, a second injection can be performed (see Fig. 27.2). This is unusual in our experience.

It is known that all snoring treatments (with the possible exception of palatal implants for which there are limited long-term data) have reduced effectiveness over time. This is likely the result of the softening and/or remodeling of scar tissue within the soft palate that occurs over time. Fortunately, it has been demonstrated that repeating IS after a relapse of snoring can be effective.9 In fact, if it turns out that snoring treatment must be maintained with serial treatments as opposed to being cured with a single treatment, then IS lends itself well to this concept as it is simple, only mildly painful, and very inexpensive.

1. Straus JF. A new approach to the treatment of snoring. Arch Otolaryngol. 1943;38:225-229.

2. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: how to treat snoring without all the pain and expense. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(5):503-510.

3. Ross SD, Sheinhait IA, Harrison KJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature regarding the diagnosis of sleep apnea. Sleep. 2000;23(4):519-532.

4. Miyazaki S, Itasaka Y, Ishikawa K, et al. Acoustic analysis of snoring and the site of airway obstruction in sleep related respiratory disorders. Acta Otolaryngol Supp. 1998;537:47-51.

5. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. The acoustical analysis of snoring: can the probability of success be predicted? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;135(3):417–20.

6. LaFrentz JR, Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Evaluation of palatal snoring surgery in an animal model. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(4):343-352.

7. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: investigation of alternative sclerotherapy agents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(1):47-57.

8. Iseri M, Balcioglu O. Radiofrequency versus injection snoreplasty in simple snoring. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(2):224-228.

9. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: extended follow-up and new objective data. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128(5):605-615.

10. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: how to treat snoring without all the pain and expense. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(5):503-510.

11. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: extended follow-up and new objective data. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128(5):605-615.

12. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: investigation of alternative sclerotherapy agents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(1):47-57.