Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles

History

The term hernia comes from the Greek ‘hernios’, meaning offshoot or bud. Inguinal hernias were described in the Ebers Papyrus in 1552 BC,1 and were found in Egyptian mummies. Celsus is thought to have performed hernia repairs in 50 AD. Galen (b. 129 AD) described the processus vaginalis, defined hernias as a rupture of the peritoneum, and advised surgical repair.2 Ambrose Paré advocated repair of inguinal hernias in childhood in the 16th century, and condemned concomitant castration.1 In 1807, Cooper identified the transversalis fascia and the ligament associated with his name. In 1817, Cloquet observed that the processus vaginalis is often patent at birth and described femoral hernias.3,4 Marcy reported high ligation of the hernia sac in 1871.5 In 1877, von Czerny first described narrowing the inguinal canal and tightening the external inguinal ring,6,7 followed by Bassini’s description of internal inguinal ring tightening and reinforcement of the posterior canal in 1887.8 Gross reported a 0.45% recurrence rate in a large series of inguinal hernia repairs (3,874 children) in 1953.9

Incidence

Approximately 1–5% of all children will develop an inguinal hernia and a positive family history is found in about 10%.10 There is an increased incidence in twins, more frequently in male twins.11 In a series of 6,361 pediatric herniorrhaphies performed by a single surgeon, the male-to-female ratio was 5 to 1, and right-sided hernias were twice as common as those on the left.12 The mean age at diagnosis was 3.3 years.

The incidence of an inguinal hernia varies directly with the degree of prematurity. The overall incidence of inguinal hernia in premature infants is estimated to be 10–30%, whereas term newborns have a rate of 3–5%.13–15 The incidence by gender is closer to 1 : 1 in premature infants. Comorbidities such as chronic lung disease associated with prematurity may play a role in the development of an inguinal hernia.

Associations

Cystic Fibrosis

Patients with cystic fibrosis have an increased risk of an inguinal hernia, with an incidence as high as 15%.16 This heightened risk may be due to elevated intra-abdominal pressure from respiratory symptoms, but developmental and/or embryologic factors may also play a role because the risk of a hernia is also increased in unaffected siblings and parents.

Hydrocephalus

Ventriculoperitoneal shunts (VPS) are associated with an increased incidence of an inguinal hernia as well as increased chance of bilaterality, incarceration, and recurrence.17 In a series of 430 children who underwent placement of a VPS, 15% developed a hernia.18 Bilaterality was common; it occurred in nearly 50% in boys and approximately 25% of girls. Hydroceles occurred in another 6%. A large series of children with shunts found that inguinal hernias were more likely to develop in neonates than in older children and were more common in boys than in girls. The average time from placement of a VPS to hernia repair was approximately one year.19

Peritoneal Dialysis

As with VPS, patients on long-term peritoneal dialysis also have an increased risk of an inguinal hernia. Some authors even advocate searching for a patent processus during insertion of the dialysis catheter (either radiographically or via laparoscopy), and closing the sac at that time.20

Embryology and Anatomy

The inguinal canal is a six-sided cylinder. The cephalad opening is the internal inguinal ring and the caudal border is the external inguinal ring. The cephalad aspect is bordered by the internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and medial external oblique fibers. The floor is formed by the transversalis fascia and the ‘conjoint tendon.’ The anterior roof is created primarily by the aponeurosis of the external oblique. The inferior wall is composed by the inguinal ligament, lacunar ligament (medial third), and iliopubic tract (lateral third). Contents include the ilioinguinal nerve (exiting through the external inguinal ring) and in males, the spermatic cord. In females, it also contains the round ligament.21

The processus vaginalis is a peritoneal diverticulum extending through the internal inguinal ring into the inguinal canal. It can be seen by 3 months of fetal life.22 The somatic base of this diverticulum is the transversalis portion of the endoabdominal fascia. The gonads form on the anteromedial nephrogenic ridges in the retroperitoneum during the 5th week of gestation. The gonads are attached to the scrotum by the gubernaculum in the male and to the labia via the round ligament in the female. Gonadal descent begins by 3 months’ gestation, and the testis reaches the internal inguinal ring by about 7 months. Descent of the testis is thought to be directed in the abdominal phase by insulin-like 3 protein, a product of the Leydig cells, and directed in the second phase by androgens and release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) from the genitofemoral nerve (via fetal androgen release).23,24 CGRP appears to mediate closure of the patent processus vaginalis (PPV), although this process is not completely understood.24

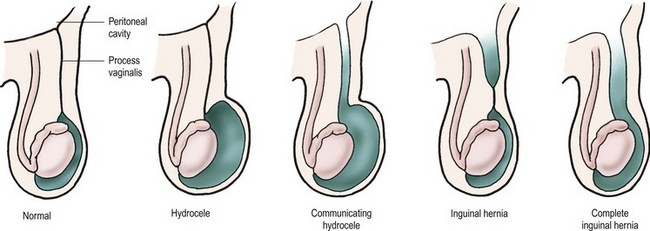

The testis begins to descend down the canal by the seventh month of fetal life preceded and guided by the processus vaginalis.22,24,25 The processus, which is located anterior and medial to the cord structures, gradually obliterates, and the scrotal portion forms the tunica vaginalis. The female anlage of the processus vaginalis is the canal of Nuck, a structure that leads to the labia majora. This also closes by about 7 months of fetal life, and ovarian descent is arrested in the pelvis.22 The precise incidence of PPV in newborns is unknown and depends on gender and gestational age. It is estimated to be 40–60%, but may be lower or higher.26 However, at autopsy, only 5% of adults have a PPV.22 PPVs can still close after birth, but this is felt less likely to occur with increasing age. It is failure of the PPV to close that results in an indirect inguinal hernia. As mentioned, the factors driving PPV closure are incompletely understood. Intra-abdominal pressure probably plays a role because disorders with increased abdominal pressure/fluid (e.g., ascites, VPS) are associated with an increased incidence of indirect inguinal hernias and an increased incidence of bilaterality.17 Indirect inguinal hernias are more common on the right. The various clinical findings related to the processus vaginalis are illustrated in Figure 50-1.

FIGURE 50-1 From left, configurations of hydrocele and hernia in relation to patency of the processus vaginalis.

The layers of the abdominal wall contribute to the layers of the testis and spermatic cord as the gonad descends. The internal spermatic fascia is a continuation of the transversalis fascia, the cremaster muscle derives from the internal oblique, and the external spermatic fascia originates from the external oblique aponeurosis. The processus vaginalis envelops the testis as the visceral and parietal layers of the tunica vaginalis.22

Clinical Presentation

A common occurrence is a normal examination in combination with a suggestive history. Cell phone picture documentation by the parents has become commonplace. A good history is acceptable as an indication for operation. False-negative explorations are rare. In the previously mentioned series of 6,361 hernia repairs by a single surgeon (definitive inguinal hernia on examination was the indication for operation), there was only one false-negative exploration (0.02%).12

Children are often referred for inguinal pain in the absence of any history of bulging or swelling, often with a normal physical examination. Other sources such as musculoskeletal strain, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary abnormalities should be excluded before operative intervention. Diagnostic transumbilical laparoscopy is useful in a small subset with equivocal examinations or persistent symptoms and no other apparent cause.

Ancillary findings such as a ‘silk glove sign’ (feeling the thickened peritoneum of the patent processus as the cord is palpated) or examination under anesthesia are of variable reliability.27,28 Radiologic diagnostic aids are not generally necessary or helpful. Ultrasonography (US) can be used to identify a PPV indirectly via widening of the internal inguinal ring (more than 4–5 mm is positive), but the technique is highly operator dependent and not widely used in children.29,30 It is not generally necessary to restrict an asymptomatic child’s activities until repair is scheduled, but prompt repair may decrease interim incarceration, particularly in the very young.

Hydrocele

The management of asymptomatic hydroceles in infants is somewhat controversial. There is general agreement that a noncommunicating, asymptomatic hydrocele in an infant should simply be followed. One recent study found that 89% of 121 infants who were followed resolved by 1 year of age.31 The duration of observation varies by surgeon, with most recommending operation by one or two years of age if the hydrocele fails to resolve or if a clinical hernia is apparent.20,32

Expectant management has been extended by some authors to infants with communicating hydroceles (and therefore PPVs). In a 2010 report, in 110 infant boys with an apparent communicating hydrocele, 63% had complete resolution without operation by a mean age of nearly one year.33 Interim incarceration did not occur in this series.

Many authors recommend operation for an infant with a giant hydrocele, although the definition is subjective and variable. Most surgeons also repair hydroceles of the cord.34

Excision of the hydrocele sac is not necessary. The fluid should be evacuated, and the distal sac is opened widely. Large or thick sacs may be everted behind the cord (Bottle procedure).35

Hydroceles in adolescents are often a complication of varicocelectomy. A de novo hydrocele in this age group may represent an inguinal hernia or simply an idiopathic hydrocele. A thorough history and physical examination to exclude communication hernia should be performed. Also, an ultrasound (particularly if the testis is not palpable, since a reactive hydrocele accompanies about 15% of testicular tumors) should be obtained. A trans-scrotal hydrocelectomy is appropriate in adolescents in the absence of signs of hernia or tumor. Otherwise an inguinal approach is best.36 Transumbilical diagnostic laparoscopy for evaluation for a PPV is a good option in equivocal cases.

An abdominoscrotal hydrocele is an hourglass-shaped collection with both an inguinoscrotal and abdominal component. A combined inguinal and laparoscopic approach may be helpful.37

Incarceration

The incidence of hernia incarceration is variable and ranges from 12–17%.12,38,39 Younger age and prematurity are risk factors for incarceration.40 The mean age of patients with incarceration is significantly lower than that of those who undergo elective repair.12,41

Once an incarcerated hernia is reduced, a delay of 24 to 48 hours to allow resolution of edema is reasonable. Reliability of the family as well as clinical (very difficult reduction) and geographic considerations may dictate the need for admission and observation before definitive repair. Overall, 90–95% of incarcerated hernias can be successfully reduced.42 In one report, only 8% required emergency operation out of 743 incarcerated hernias.12 Two children required bowel resection.

Urgent operation is necessary if reduction fails. The hernia may reduce with induction of general anesthesia. If so, the hernia sac should be opened and inspected. The presence of enteric contents or bloody fluid mandates either open exploration via separate incision or La Roque maneuver (incision in the transversalis fascia through the same inguinal skin incision) or, more commonly, laparoscopic evaluation. It may be necessary to open the internal inguinal ring laterally to reduce the bowel. Some surgeons approach an incarcerated hernia by transumbilical laparoscopy to both reduce the hernia and evaluate the bowel.43,44 There is some evidence that the laparoscopic approach is associated with fewer complications.45

Intestinal injury requiring treatment is rare (1% to 2%), even with incarceration.12 The hernia sac is often quite edematous and friable, and repair of the hernia can be quite difficult. The risk of recurrence is significantly increased. We do not routinely employ laparoscopy looking for a contralateral PPV in patients with incarceration.

The testis on the incarcerated side is often edematous and somewhat cyanotic. Unless the gonad is frankly necrotic, it should be preserved. The parents of any boy with an incarcerated hernia should be counseled about the possibility of testicular loss or atrophy, but the incidence of this complication is only 2–3%.42,46 Incarceration of an ovary in a hernia sac may not always impair its blood supply, but most pediatric surgeons will promptly (but not emergently) repair the hernia in a girl even with an asymptomatic, nontender incarcerated ovary.47

Management

Anesthesia

There are no good data comparing regional to general anesthesia for pediatric inguinal hernia repair. A 2003 Cochrane meta-analysis of available data regarding this issue in premature infants concluded: ‘There is no reliable evidence from the trials reviewed concerning the effect of spinal as compared to general anesthesia on the incidence of postoperative apnea, bradycardia, or oxygen desaturation in ex-preterm infants undergoing herniorrhaphy.’48

Overnight hospitalization is not necessary after inguinal hernia repair for healthy children or term infants. However, the risk of postoperative apnea and bradycardia is increased in premature infants and overnight monitoring may be necessary. The postconceptual age (gestational age plus chronologic age) is commonly used to decide which infants require overnight admission. Several studies have addressed this issue.49,50 A review of 127 premature infants admitted after inguinal hernia repair found a incidence of apnea of about 5%, and attempted to identify factors associated with a higher risk (history of prior apnea, lower gestational age and birth weight, comorbidities).50 A less than 1% risk of postoperative apnea was found in former premature infants greater than 56 weeks postconceptual age in a comprehensive analysis of eight prospective studies.51 Sixty weeks postconceptual age is widely used as a cut-off for admission (although there is substantial institutional variability). However, a more recent retrospective review at our hospital demonstrated a low incidence of adverse events after 50 weeks postconceptual age.52

Timing

As premature infants have an increased incidence of an inguinal hernia, this is a common diagnosis in the neonatal intensive care unit. The incidence of bowel incarceration in premature infants is significantly increased (three times in one large series).12 Many institutions use 2 kg as a lower limit for repair in asymptomatic and otherwise relatively healthy newborns. We usually repair the hernia before discharge to avoid the need for readmission for herniorrhaphy and to decrease the risk of incarceration.46,53–55 However, this depends on other comorbidities. One recent study compared repair before discharge or as an outpatient, and found an increased length of hospitalization in the former group (largely from respiratory complications) and a low incidence of incarceration in the latter group.56 However, others have found that in-house repair is preferable due to a lower incarceration rate after discharge.57,58

Open Repair Technique

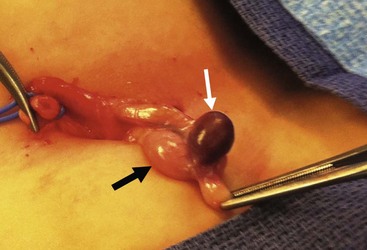

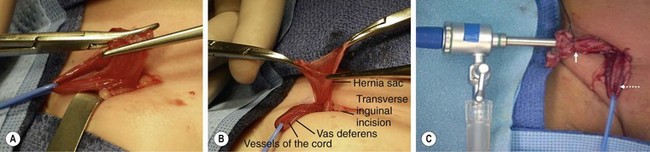

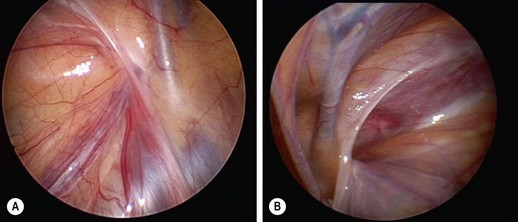

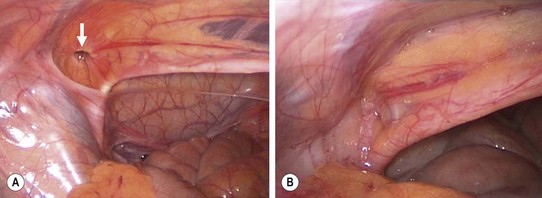

Pediatric indirect inguinal hernias are usually repaired through an inguinal crease incision by incising the external oblique aponeurosis to the internal inguinal ring. After the ilioinguinal nerve is identified, the antero-medial hernia sac is grasped and the vas and vessels (in the usual male hernia) are pushed away from the sac (Fig. 50-2A). The sac is clamped and divided (Fig. 50-2B). A high ligation is performed after the sac is opened and inspected. If contralateral laparoscopic evaluation is performed, a small cannula can be gently advanced through the opened sac (Fig. 50-2C). A 70°, 2.7 mm telescope allows examination of the contralateral side (Figs 50-3 and 50-4).

FIGURE 50-2 (A) After a right inguinal incision in an infant boy, the sac has been separated from the vas and vessels by grasping the sac and ‘teasing’ the cord structures away. The hernia sac, located anteromedial to the cord, has been carefully separated from the vas and vessels (vessel loop) and is clamped in preparation for division of the sac. (B) In preparation for diagnostic laparoscopy to evaluate the contralateral internal ring, the sac is opened. A vessel loop is around the cord structures. (C) A cannula has been introduced into the opened hernia sac and the sac has been tied (solid arrow) to keep the abdomen insufflated. The cord structures (dotted arrow) are retracted with the vessel loop.

FIGURE 50-3 Laparoscopic evaluation of the contralateral inguinal region is used by many pediatric surgeons. (A) A view of the left internal ring shows the inverted ‘V’ of the laterally located gonadal vessels and the medial vas. At the apex of the ‘V,’ the left internal inguinal ring is completely closed. (B) A right-patent process vaginalis is seen in a 7-year-old with a known left inguinal hernia.

FIGURE 50-4 (A) In a small percentage of cases, a veil of peritoneum will cover the contralateral internal ring and obscure the laparoscopic findings such that the surgeon is not completely certain whether a contralateral patent processus vaginalis (CPPV) is present. In this situation, a technique has been reported to retract the veil of tissue. (B) A silver probe is introduced in the contralateral lower abdomen/flank and used to retract the veil medially so that the 70-degree telescope can then look down the possible CPPV. (C) In this patient, a significant CPPV was visualized once the veil of peritoneum was retracted medially. (Adapted from Geiger JD. Selective laparoscopic probing for a contralateral patent processus vaginalis reduces the need for a contralateral exploration in inconclusive cases. J Pediatr Surg 2000;35:1151–4.)

There is an uncommon but disturbing incidence of late inguinal abscess formation related to the use of silk suture material for ligation of the sac.59,60 For this reason, we now prefer absorbable sutures. The sac may be twisted before ligation, but too much twisting may draw the vas and cord structures into the base of the sac where they risk being inadvertently ligated. Removing the distal sac may increase the risk of injury to the cord structures and the testis, and is not necessary. Distal hydroceles should be opened widely and drained. It is important to ensure that the testis is in the scrotum at the conclusion of the procedure to avoid iatrogenic cryptorchidism.

Sliding hernias are uncommon but are more frequent in females, with an incidence as high as 20–40%. A fallopian tube or ovary may be involved. The bladder may constitute the medial wall of the sac in infants.61 The appendix (Amyand’s hernia) may form a sliding component on the right. More distal ligation of the sac with proximal purse-string inversion is our preferred management technique for sliding inguinal hernias.62

Laparoscopic Repair Technique

An accurate description of the current state of pediatric laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is a moving target. In 2002, Schier and colleagues reported a large series of 933 laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs in children with a mean age of 3.2 years and a recurrence rate of 3.4%.63 Other reports followed with a similarly increased recurrence rate compared to open repairs.64 However, in the last few years, there have been several large series of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs in infants and children with low recurrence and complication rates.65–69

A recent meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials and four observational studies compared 1,543 laparoscopic repairs to 657 open repairs and found no difference in recurrence, a decreased incidence of metachronous hernia with laparoscopy, and decreased operative time for bilateral repairs done laparoscopically.65 Another 2011 meta-analysis of 2,699 children found no statistically significant difference in recurrence rates, but an increased operative time with laparoscopic unilateral repair.66 The authors confirmed the decreased incidence of metachronous hernia in the laparoscopic group. Improvement in laparoscopic recurrence rates appears to be due to various technical modifications of the procedure. Generally, it appears that extracorporeal knot-tying yields superior results. Several recent large series have reported recurrence rates less than 0.5%.67–69

Contralateral Evaluation

Contralateral exploration for unilateral inguinal hernia in children has a long and controversial history. Meta-, cost-, and decision-tree analyses have all been performed.70–74 Routine contralateral open exploration is probably not justified. Surveys of pediatric surgeons have demonstrated a decrease in the practice of routine contralateral exploration over time, while laparoscopic evaluation of the contralateral side via the ipsilateral hernia opening has grown in popularity.75,76

Incidence of PPV

Diagnostic laparoscopy in children with a unilateral hernia allows identification of a contralateral PPV (see Figs 50-3 and 50-4), with the caveat that (1) some PPVs will not develop into clinically symptomatic hernias and (2) it may be difficult to distinguish a peritoneal fold from a true PPV. This technique was initially described in the early 1990s by Lobe and Holcomb.77,78

The mean additional operating time is minimal in most reports (four to five minutes).79 There is some economic justification for this approach as well,71,80 although not all other reports agree.80 The reported incidence of PPV in unilateral hernia repairs has varied, but is typically 25–40%.

In a 2011 review of 684 children, contralateral laparoscopic evaluation was positive in 32% of right-sided and 42% of left-sided hernias.81 A similar report of 1,001 children found a 24% incidence of PPV, decreasing with age and male gender.79 A contralateral PPV was found in 38% of 453 children, decreasing with age.82 Younger age, female gender, and a left-sided unilateral hernia have been used as selection criteria, while some authors argue for routine diagnostic contralateral laparoscopy in all children.81–83

Contralateral laparoscopic evaluation is impossible in about 5% of children, usually due to a very small hernia sac, or simply poor visualization.28 Contralateral hernias after successful but negative contralateral evaluation been reported in 1.6–2.5% of patients.81,84

Incidence of Metachronous Hernia

Many reports have addressed the incidence of a contralateral clinical hernia after unilateral repair, and most have documented a 6–10% incidence.74,85–88 Left-sided initial hernias may be associated with an increased risk of a symptomatic contralateral hernia. Younger patient age and prematurity have also been identified as markers for an increased risk of metachronous hernia.

A 2007 meta-analysis of 49 papers with data on 22,846 children found an overall incidence of 7.2%, with no gender difference.89 However, a left-sided inguinal hernia had a significantly higher risk than right-sided (10.2% vs 6.3%). A prospective study of 548 patients followed for a mean of two years found that 8.8% developed a contralateral hernia, with an average interval of six months. The incidence was higher in younger infants, premature infants, and females.90 An older meta-analysis of 15,310 patients from several studies found a 7% incidence of a metachronous hernia.72 A prospective study in which 222 children with unilateral hernia underwent laparoscopy, and 67 clinically followed without repair of an incidental PPV noted that 6.8% developed a metachronous hernia.91 MacGregor et al. followed 160 children under age 10 years who underwent a unilateral inguinal hernia repair over a 32-year period. Ninety-six percent were followed for a mean of 20 years. Over this time, 29% developed a symptomatic contralateral inguinal hernia. Interestingly, the authors did not recommend routine contralateral exploration due to its risks (in the open era).92

Pain Management

A randomized prospective trial of local instillation of long-acting analgesics (e.g., bupivacaine) versus caudal block for postoperative pain control in infants and children after inguinal hernia repair demonstrated no significant difference in pain control.93 Instillation of local anesthetics into the wound (‘splash technique’) is effective as well. Ilioinguinal nerve block was also shown to provide better analgesia than transverse abdominis plane block in a prospective randomized trial.94

Complications

Recurrence

The risk of recurrence after an elective inguinal hernia repair is less than 1% in several large series.12,95 It is higher in premature infants, in children with incarcerated hernias, and those with associated diseases (e.g., connective tissue disorder, VPS).17,95 Recurrence rates can be as high as 50% in children with connective tissues disorders and mucopolysaccharidoses. A recurrent hernia even can be the presenting symptom in these diseases.95 Recurrence rates may also be higher in teenagers.12

Injury to the Spermatic Cord or Testis

Injury to the spermatic cord or testis is a rare occurrence in elective hernia repairs, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 1,000.12 The true incidence may be underestimated since instrument manipulation of the cord causes microscopic injury and scarring in animal models.96,97 A recognized injury to the vas should be managed by immediate repair with fine (8-0) suture under magnification, and the family should be informed of the event. In institutions in which hernia sacs are routinely examined by a pathologist, mesonephric or adrenal rests are occasionally seen, but do not indicate injury to the vas. A review of 7,314 male pediatric hernia specimens over a 14-year period at a major children’s hospital found either vas deferens or epididymis in 0.53% of specimens.98 Recent reviews of the subject have concluded that routine histologic examination of male hernia sacs is not necessary.99,100 Testicular atrophy from vascular injury during routine inguinal hernia repair is also uncommon.

Other Complications

In a recent retrospective review of 268 patients less than 2 years of age (98 of whom were premature), prematurity was a marker for an increased risk of complications following inguinal hernia repair (28% vs 12% in term infants).58

Chronic pain after herniorrhaphy, although seen in adults, is uncommon in children. However, one recent review of 651 adults who had undergone inguinal hernia repair before age five years found that 13.5% of the patients reported occasional mild groin pain, usually related to physical activity (pain was frequent or moderate in only 2%).101

Loss of domain due to a huge hernia is another problem more frequently seen in adults, but it can occur in infants or children and may require staged repair or other measures.102 Iatrogenic cryptorchidism from failure to replace the testis in normal anatomic position is a rare occurrence (<1%). Bladder injury in infants in whom the medial wall of the sac contains urinary bladder is also a rare complication.103

Mortality directly related to inguinal hernia or its repair is exceedingly rare (<1%).

Special Issues

Direct Inguinal Hernia

Direct inguinal hernias are very unusual in children, even older teenagers.104 However, the incidence was as high as 4% in one laparoscopic series.105Some recurrences after indirect inguinal hernia repair are direct inguinal hernias. Direct inguinal hernias in children are managed as standard ‘adult’ inguinal hernia repairs. Our preference is for a McVay repair (approximation of the transversalis aponeurotic arch and internal oblique aponeurosis to the anterior ileopubic tract and shelving edge of the inguinal ligament). Laparoscopic repair is another option.

Femoral Hernia

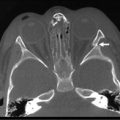

Femoral hernias are relatively equally distributed by gender,106,107 but are much less common than indirect inguinal hernias. In two combined series of over 10,000 patients, 0.2% of hernias were femoral.104,108 Most (two-thirds) are not suspected before operation (Fig. 50-5).104,107 A mass below the inguinal ligament should alert the clinician to this possibility. Femoral hernias are bilateral in 10 to 20%. Recurrence is increased after femoral hernia repair compared with indirect inguinal herniorrhaphy.106 McVay repair has been the standard technique for repair, but laparoscopic and mesh-plug repairs have been used as well.109,110

FIGURE 50-5 This young girl presented with symptoms suggestive, but not conclusive, of a left femoral hernia. Therefore, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed through the umbilicus to confirm the diagnosis prior to an inguinal approach and a McVay repair. (A) The internal opening (arrow) to the femoral hernia is seen. (B) After the McVay repair, the femoral defect is closed.

Absent or Atrophic Vas

Occasionally, a small or absent vas is found during inguinal hernia repair. Renal ultrasound is necessary because of associated ipsilateral renal agenesis.111,112 This should also prompt a workup for cystic fibrosis. Congenital absence (bilateral or unilateral) of the vas is a heterogeneous disorder, largely due to mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene. Differing genotypes are noted with congenital absence of the vas as an isolated entity versus congenital absence of the vas in association with renal anomalies.113

Disorders of Sexual Differentiation

The finding of a testis during repair of a female hernia should raise the suspicion of congenital androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) or true hermaphroditism.114 As many as 1% of female infants with inguinal hernias will have CAIS.115 Bilateral hernias in girls are not associated with a higher risk of CAIS than is a unilateral hernia. Conversely, as many as 75% of CAIS patients present with a hernia.

At the time of hernia repair (or later as a separate procedure), laparoscopy is a good way to evaluate for the presence or absence of the fallopian tube, ovary, and uterus. The gonad should be sampled. Some advocate rectal examination to palpate the uterus. Vaginoscopy is another option. In the presence of CAIS, an absent cervix will be found, and vaginal length is shortened in this syndrome.115 Karyotyping and pelvic ultrasound should also be performed. Eventual gonadectomy will be necessary, although the optimal timing is controversial.

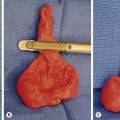

Other

Incidentally discovered yellow nodules along the spermatic cord or testis are due to adrenal rests. In one study, the incidence was 1.7% in 1,862 pediatric hernia repairs.116 These should be removed if possible. Splenogonadal fusion is a very rare entity that may be difficult to distinguish preoperatively from a testicular neoplasm (Fig. 50-6). Frozen section confirmation usually allows gonadal preservation.

References

1. Lau, WY, History of treatment of groin hernia. World J Surg [Internet] 2002;26(6):748–75. http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/s00268-002-6297-5

2. Lascaratos, JG, Tsiamis, C, Kostakis, A. Surgery for inguinal hernia in Byzantine Times (A.D. 324-1453): First Scientific Descriptions. World J Surg. 2003; 27:1165–1169.

3. Cloquet’s hernia (www.whonamedit.com) [Internet]. whonamedit.com. [cited 2012 Jun. 21]. Available from http://www.whonamedit.com/synd.cfm/2654.html.

4. Cloquet, J, Recherches Anatomiques sur les Hernies de l’Abdomen Paris, 1817.

5. Marcy, H. A new use of carbolized cat gut ligatures. Boston Med Surg J. 1871; 85:315–316.

6. Czerny Von, V. Studien zur Radikalbehandlung der Hernien. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1877; 27:497–528. [–554–578].

7. Sachs, M, Damm, M, Encke, A. Historical evolution of inguinal hernia repair. World J Surg. 1997; 21:218–223.

8. Bassini, E. Nuovo Metodo Operativo per la Cura dell’Ernia Inguinale. R Stabilimento Prosperini. 1889.

9. Gross, RE. Inguinal Hernia. The Surgery of Infancy and Childhood. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1953.

10. Bronsther, B, Abrams, MW, Elboim, C. Inguinal hernias in children–a study of 1,000 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1972; 27:522–525.

11. Bakwin, H. Indirect inguinal hernia in twins. J Pediatr Surg. 1971; 6:165–168.

12. Ein, SH, Njere, I, Ein, A. Six thousand three hundred sixty-one pediatric inguinal hernias: A 35-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 1:980–986.

13. Harper, RG, Garcia, A, Sia, C. Inguinal hernia: A common problem of premature infants weighing 1,000 grams or less at birth. Pediatrics. 1975; 56:112–115.

14. Kumar, VHS, Clive, J, Rosenkrantz, TS, et al. Inguinal hernia in preterm infants. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002; 18:147–152.

15. Grosfeld, JL. Current concepts in inguinal hernia in infants and children. World J Surg. 1989; 13:506–515.

16. Holsclaw, DS, Shwachman, H. Increased incidence of inguinal hernia, hydrocele, and undescended testicle in males with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1971; 48:442–445.

17. Celik, A, Ergün, O, Arda, MS, et al. The incidence of inguinal complications after ventriculoperitoneal shunt for hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005; 21:44–47.

18. Clarnette, TD, Lam, SK, Hutson, JM. Ventriculo-peritoneal shunts in children reveal the natural history of closure of the processus vaginalis. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:413–416.

19. Wu, JC, Chen, YC, Liu, L, et al. Younger boys have a higher risk of inguinal hernia after Ventriculo-Peritoneal Shunt: A 13-year nationwide cohort study. JACS. 2012; 214:845–851.

20. Glick, PL, Boulanger, SC. Inguinal Hernias and Hydroceles. In Coran AG, Adzick NS, Krummel T, et al, eds.: Pediatric Surgery, 7th ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

21. Ilioinguinal nerve [Internet]. en.wikipedia.org. [cited 2012 Jun. 27]. Available from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilioinguinal_nerve.

22. Gray, SW, Skandalakis, JE. Embryology for surgeons, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994.

23. Lie, G, Hutson, JM. The role of cremaster muscle in testicular descent in humans and animal models. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011; 27:1255–1265.

24. Clarnette, TD, Hutson, JM. The genitofemoral nerve may link testicular inguinoscrotal descent with congenital inguinal hernia. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996; 66:612–617.

25. Heyns, CF. The gubernaculum during testicular descent in the human fetus. J Anat. 1987; 153:93–112.

26. Rowe, MI, Copelson, LW, Clatworthy, HW. The patent processus vaginalis and the inguinal hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1969; 4:102–107.

27. Luo, C-C, Chao, H-C. Prevention of unnecessary contralateral exploration using the silk glove sign (SGS) in pediatric patients with unilateral inguinal hernia. Eur J Pediatr. 2006; 166:667–669.

28. Valusek, PA, Spilde, TL, Ostlie, DJ, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation for contralateral patent processus vaginalis in children with unilateral inguinal hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006; 166:650–653.

29. Chen, KC, Chu, CC, Chou, TY, et al. Ultrasonography for inguinal hernias in boys. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:1784–1787.

30. Erez, I, Rathause, V, Vacian, I, et al. Preoperative ultrasound and intraoperative findings of inguinal hernias in children: A prospective study of 642 children. J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37:865–868.

31. Naji, H, Ingolfsson, I, Isacson, D, et al. Decision making in the management of hydroceles in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr. 2012; 171:807–810.

32. Lau, ST, Lee, Y-H, Caty, MG. Current management of hernias and hydroceles. Sem Pediatr Surg. 2007; 16:50–57.

33. Koski, M, Makari, J, Adams, M. Infant communicating hydroceles–do they need immediate repair or might some clinically resolve? J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:590–593.

34. Chang, Y-T, Lee, J-Y, Wang, J-Y, et al. Hydrocele of the spermatic cord in infants and children: Its particular characteristics. Urology. 2010; 76:82–86.

35. Andrews, EW. The “Bottle Operation” method for the radical cure of hydrocele. Ann Surg. 1907; 46:915–918.

36. Wilson, J, Aaronson, D, Schrader, R. Hydrocele in the pediatric patient: Inguinal or scrotal approach? J Urol. 2008; 180:1427–1727.

37. Martin, K, Emil, S, Laberge, J-M. The value of laparoscopy in the management of abdominoscrotal hydroceles. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012; 22:419–421.

38. Stephens, BJ, Rice, WT, Koucky, CJ, et al. Optimal timing of elective indirect inguinal hernia repair in healthy children: Clinical considerations for improved outcome. World J Surg. 1992; 16:952–956.

39. Rowe, MI, Clatworthy, HW. Incarcerated and strangulated hernias in children. A statistical study of high-risk factors. Arch Surg. 1970; 101:136–139.

40. Palmer, BV. Incarcerated inguinal hernia in children. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1978; 60:121–124.

41. Stylianos, S, Jacir, NN, Harris, BH. Incarceration of inguinal hernia in infants prior to elective repair. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:582–583.

42. Puri, P, Guiney, EJ, O’Donnell, B. Inguinal hernia in infants: The fate of the testis following incarceration. J Pediatr Surg. 1984; 19:44–46.

43. Shalaby, R, Shams, AM, Mohamed, S, et al. Two-trocar needlescopic approach to incarcerated inguinal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2007; 42:1259–1262.

44. Takehara, H, Hanaoka, J, Arakawa, Y. Laparoscopic strategy for inguinal ovarian hernias in children: When to operate for irreducible ovary. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009; 19:S129–S131.

45. Nah, SA, Giacomello, L, Eaton, S, et al. Surgical repair of incarcerated inguinal hernia in children: Laparoscopic or open? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 21:8–11.

46. Nagraj, S, Sinha, S, Grant, H, et al. The incidence of complications following primary inguinal herniotomy in babies weighing 5 kg or less. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006; 22:500–502.

47. Levitt, MA, Ferraraccio, D, Arbesman, MC, et al. Variability of inguinal hernia surgical technique: A survey of North American pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37:745–751.

48. Craven, PD, Badawi, N, Henderson-Smart, DJ, et al. Regional (spinal, epidural, caudal) versus general anaesthesia in preterm infants undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy in early infancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2003.

49. Coté, CJ, Zaslavsky, A, Downes, JJ, et al. Postoperative apnea in former preterm infants after inguinal herniorrhaphy. A combined analysis. Anesthesiology. 1995; 82:809–822.

50. Murphy, JJ, Swanson, T, Ansermino, M, et al. The frequency of apneas in premature infants after inguinal hernia repair: Do they need overnight monitoring in the intensive care unit? J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 43:865–868.

51. Malviya, S, Swartz, J, Lerman, J. Are all preterm infants younger than 60 weeks postconceptual age at risk for postanesthetic apnea? Anesthesiology. 1993; 78:1076–1081.

52. Laituri, CA, Garey, CL, Pieters, BJ, et al. Overnight observation in former premature infants undergoing inguinal hernia repair. J Pediatr Surg. 2012; 47:217–220.

53. Misra, D. Inguinal hernias in premature babies: Wait or operate? Acta Paediatr. 2001; 90:370–371.

54. Lautz, TB, Raval, MV, Reynolds, M. Does timing matter? A national perspective on the risk of incarceration in premature neonates with inguinal hernia. J Pediatr. 2011; 158:573–577.

55. Miller, GG, McDonald, SE, Milbrandt, K, et al. Risk of incarceration of inguinal hernia among infants and young children awaiting elective surgery. CMAJ. 2008; 179:1001–1005.

56. Lee, SL, Gleason, JM, Sydorak, RM. A critical review of premature infants with inguinal hernias: Optimal timing of repair, incarceration risk, and postoperative apnea. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:217–220.

57. Vaos, G, Gardikis, S, Kambouri, K, et al. Optimal timing for repair of an inguinal hernia in premature infants. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010; 26:379–385.

58. Gholoum, S, Baird, R, Laberge, J-M, et al. Incarceration rates in pediatric inguinal hernia: Do not trust the coding. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:1007–1011.

59. Calkins, CM, St Peter, SD, Balcom, A, et al. Late abscess formation following indirect hernia repair utilizing silk suture. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007; 23:349–352.

60. Nagar, H. Stitch granulomas following inguinal herniotomy: A 10-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:1505–1507.

61. Redman, JF, Jacks, DW, O’Donnell, PD. Cystectomy: A catastrophic complication of herniorrhaphy. J Urol. 1985; 133:97–98.

62. Bevan, A. Sliding inguinal hernia of the ascending colon and cecum, the descending colon, sigmoid, and the bladder. Ann Surg. 1930; 92:792–794.

63. Schier, F, Montupet, P, Esposito, C. Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy in children: A three-center experience with 933 repairs. J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37:395–397.

64. Schier, F. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair-A prospective personal series of 542 children. J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41:1081–1084.

65. Yang, C, Zhang, H, Pu, J, et al. Laparoscopic vs open herniorrhaphy in the management of pediatric inguinal hernia: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:1824–1834.

66. Alzahem, A. Laparoscopic versus open inguinal herniotomy in infants and children: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011; 27:605–612.

67. Tam, YH, Lee, KH, Sihoe, JDY, et al. Laparoscopic hernia repair in children by the hook method: A single-center series of 433 consecutive patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:1502–1505.

68. Endo, M, Watanabe, T, Nakano, M, et al. Laparoscopic completely extraperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia in children: A single-institute experience with 1,257 repairs compared with cut-down herniorrhaphy. Surg Endosc. 2009; 23:1706–1712.

69. Chen, K, Xiang, G, Wang, H, et al. Towards a near-zero recurrence rate in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair for pediatric patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011; 21:445–448.

70. Burd, RS, Heffington, SH, Teague, JL. The optimal approach for management of metachronous hernias in children: A decision analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 36:1190–1195.

71. Miltenburg, DM, Nuchtern, JG, Jaksic, T, et al. Laparoscopic evaluation of the pediatric inguinal hernia–A meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:874–879.

72. Miltenburg, DM, Nuchtern, JG, Jaksic, T, et al. Meta-analysis of the risk of metachronous hernia in infants and children. Am J Surg. 1991; 174:741–744.

73. Muensterer, OJ, Woller, T, Metzger, R, et al. [The economics of contralateral laparoscopic inguinal hernia exploration: Cost calculation of herniotomy in infants.]. Chirurg. 2008; 79:1065–1071.

74. Nataraja, RM, Mahomed, AA. Systematic review for paediatric metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia: A decreasing concern. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011; 27:953–961.

75. Antonoff, MB, Kreykes, NS, Saltzman, DA, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery hernia survey revisited. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:1009–1014.

76. Wiener, ES, Touloukian, RJ, Rodgers, BM, et al. Hernia survey of the Section on Surgery of the American Academy of Pediatrics. J Pediatr Surg. 1996; 31:1166–1169.

77. Lobe, TE, Schropp, KP. Inguinal hernias in pediatrics: Initial experience with laparoscopic inguinal exploration of the asymptomatic contralateral side. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1992; 2:135–140.

78. Holcomb, GW, III., Brock, JW, Morgan, WM. Laparoscopic evaluation for a contralateral patent processus vaginalis. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:970–973.

79. Saad, S, Mansson, J, Saad, A, et al. Ten-year review of groin laparoscopy in 1001 pediatric patients with clinical unilateral inguinal hernia: An improved technique with transhernia multiple-channel scope. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:1011–1014.

80. Lee, SL, Sydorak, RM, Lau, ST. Laparoscopic contralateral groin exploration: Is it cost effective? J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:793–795.

81. Draus, JM, Kamel, S, Seims, A, et al. The role of laparoscopic evaluation to detect a contralateral defect at initial presentation for inguinal hernia repair. Am Surg. 2011; 77:1463–1466.

82. Lazar, DA, Lee, TC, Almulhim, SI, et al. Transinguinal laparoscopic exploration for identification of contralateral inguinal hernias in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:2349–2352.

83. Yerkes, EB, Brock, JW, Holcomb, GW, III., et al. Laparoscopic evaluation for a contralateral patent processus vaginalis: Part III. Urology. 1998; 51:480–483.

84. Juang, D, Garey, CL, Ostlie, DJ, et al. Contralateral inguinal hernia after negative laparoscopic evaluation: A rare but real phenomenon. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012; 22:200–202.

85. Chertin, B, De Caluwé, D, Gajaharan, M, et al. Is contralateral exploration necessary in girls with unilateral inguinal hernia? J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:756–757.

86. Shabbir, J, Moore, A, O’Sullivan, JB, et al. Contralateral groin exploration is not justified in infants with a unilateral inguinal hernia. Ir J Med Sci. 2003; 172:18–19.

87. Ballantyne, A, Jawaheer, G, Munro, FD. Contralateral groin exploration is not justified in infants with a unilateral inguinal hernia. Br J Surg. 2001; 88:720–723.

88. Given, JP, Rubin, SZ. Occurrence of contralateral inguinal hernia following unilateral repair in a pediatric hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 1989; 24:963–965.

89. Ron, O, Eaton, S, Pierro, A. Systematic review of the risk of developing a metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia in children. Br J Surg. 2007; 94:804–811.

90. Tackett, LD, Breuer, CK, Luks, FI, et al. Incidence of contralateral inguinal hernia: A prospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34:684–687.

91. Maddox, MM, Smith, DP. A long-term prospective analysis of pediatric unilateral inguinal hernias: Should laparoscopy or anything else influence the management of the contralateral side? J Pediatr Urol. 2008; 4:141–145.

92. McGregor, DB, Halverson, K, McVay, CB. The unilateral pediatric inguinal hernia: Should the contralateral side by explored? J Pediatr Surg. 1980; 15:313–317.

93. Machotta, A, Risse, A, Bercker, S, et al. Comparison between instillation of bupivacaine versus caudal analgesia for postoperative analgesia following inguinal herniotomy in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003; 13:397–402.

94. Fredrickson, MJ, Paine, C, Hamill, J. Improved analgesia with the ilioinguinal block compared to the transverse abdominis plane block after pediatric inguinal hernia surgery: A prospective randomized trial. Pediatr Anaesth. 2010; 20:1022–1027.

95. Grosfeld, JL, Minnick, K, Shedd, F, et al. Inguinal hernia in children: Factors affecting recurrence in 62 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1991; 26:283–287.

96. Shandling, B, Janik, JS. The vulnerability of the vas deferens. J Pediatr Surg. 1981; 16:461–464.

97. Abasiyanik, A, Güvenc, H, Yavuzer, D, et al. The effect of iatrogenic vas deferens injury on fertility in an experimental rat model. J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 32:1144–1146.

98. Steigman, CK, Sotelo-Avila, C, Weber, TR. The incidence of spermatic cord structures in inguinal hernia sacs from male children. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999; 23:880–885.

99. Miller, GG, McDonald, SE, Milbrandt, K, et al. Routine pathological evaluation of tissue from inguinal hernias in children is unnecessary. Can J Surg. 2003; 46:117–119.

100. Kim, B, Leonard, MP, Bass, J, et al. Analysis of the clinical significance and cost associated with the routine pathological analysis of pediatric inguinal hernia sacs. J Urol. 2011; 186:1620–1624.

101. Aasvang, EK, Kehlet, H. Chronic pain after childhood groin hernia repair. J Pediatr Surg. 2007; 42:1403–1408.

102. Khozeimeh, N, Henry, MCW, Gingalewski, CA, et al. Management of congenital giant inguinal scrotal hernias in the newborn. Hernia. 2011.

103. Aloi, IP, Lais, A, Caione, P. Bladder injuries following inguinal canal surgery in infants. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010; 26:1207–1210.

104. Fonkalsrud, EW, Delorimier, A, Clatworthy, HW. Femoral and direct inguinal hernias in infants and children. JAMA. 1965; 192:597–599.

105. Gorsler, CM, Schier, F. Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy in children. Surg Endosc. 2003; 17:571–573.

106. De Caluwé, D, Chertin, B, Puri, P. Childhood femoral hernia: A commonly misdiagnosed condition. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003; 19:608–609.

107. Al-Shanafey, S, Giacomantonio, M. Femoral hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34:1104–1106.

108. Burke, J. Femoral hernia in childhood. Ann Surg. 1967; 166:287–289.

109. Adibe, OO, Hansen, EN, Seifarth, FG, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted repair of femoral hernias in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009; 19:691–694.

110. Matthyssens, LEM, Philippe, P. A new minimally invasive technique for the repair of femoral hernia in children: About 13 laparoscopic repairs in 10 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:967–971.

111. Lukash, F, Zwiren, GT, Andrews, HG. Significance of absent vas deferens at hernia repair in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1975; 10:765–769.

112. Schlegel, PN, Shin, D, Goldstein, M. Urogenital anomalies in men with congenital absence of the vas deferens. J Urol. 1996; 155:1644–1648.

113. Casals, T, Bassas, L, Egozcue, S, et al. Heterogeneity for mutations in the CFTR gene and clinical correlations in patients with congenital absence of the vas deferens. Hum Reprod. 2000; 15:1476–1483.

114. Hughes, IA, Davies, JD, Bunch, TI, et al. Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Lancet. 2012; 380:1419–1428.

115. Hurme, T, Lahdes-Vasama, T, Makela, E, et al. Clinical findings in prepubertal girls with inguinal hernia with special reference to the diagnosis of androgen insensitivity syndrome. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009; 43:42–46.

116. Ketata, S, Ketata, H, Sahnoun, A, et al. Ectopic adrenal cortex tissue: An incidental finding during inguinoscrotal operations in pediatric patients. Urol Int. 2008; 81:316–319.