Ingestion of Foreign Bodies

Esophageal Foreign Bodies

Foreign body (FB) ingestions are a common occurrence in infants and young children. The exact incidence is unknown since many cases are not reported. In 2010, the Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers noted over 116,000 cases of FB ingestion. More than 86,000 occurred in children ≤5 years of age.1 The vast majority of ingestions in children are accidental.2 The most common type of FB varies by geographic region. In the USA and Europe, coins are the most common.2,3 Other commonly ingested objects include toys, batteries, needles, straight pins, safety pins (Fig. 11-1), screws, earrings, pencils, erasers, glass, fish and chicken bones, and meat. However, in areas of the world where fish contributes a significant portion of the diet, such as in Asia, a fish bone may be the most common FB ingested in children.2,4

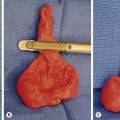

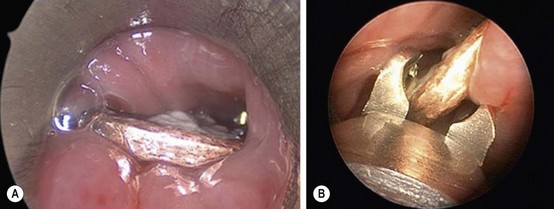

FIGURE 11-1 This child accidentally ingested this open safety pin which was able to be extracted with esophagoscopy.

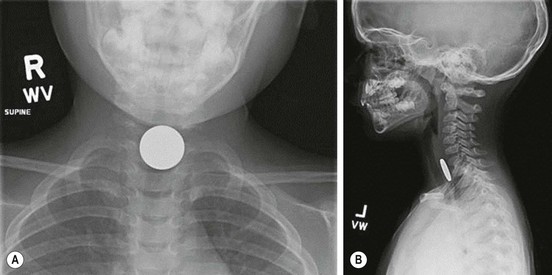

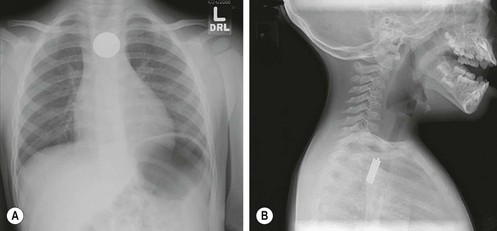

Symptoms of esophageal FB impaction are nonspecific and include drooling, poor feeding, neck and throat pain, vomiting, or wheezing. Radiopaque objects can be detected on the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral neck and chest radiographs (Fig. 11-2), while radiolucent objects may require further workup with a gastrografin esophagram or esophagoscopy depending on the symptoms and level of suspicion (Fig. 11-3).

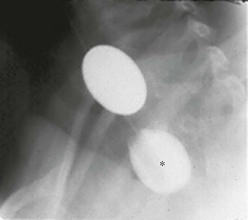

FIGURE 11-2 This 3-year-old child presented with dysphagia and drooling. (A) The anteroposterior radiograph shows a coin that appears en face in the upper esophagus. (B) The lateral view shows that the coin is posterior to the trachea, confirming its esophageal location.

FIGURE 11-3 A piece of chicken became lodged in this child’s upper esophagus. The chest radiograph was normal, but the esophagram shows the foreign material (arrow) obstructing the esophagus.

The most common round, smooth object ingested that is amenable to extraction or advancement techniques is a coin. The majority of esophageal coins will appear en face in the anteroposterior view, and from the side on the lateral radiograph (see Fig. 11-2). On occasion, more than one coin will have been ingested (Fig. 11-4).

FIGURE 11-4 This infant was seen in the emergency department for swallowing difficulty and drooling. (A) Anteroposterior radiograph shows a coin in the upper esophagus. (B) However, on the lateral view, there are actually four coins superimposed on one another. The lateral view is very helpful for the purpose of determining whether more than one coin has been ingested.

The location of the object on the radiograph is important in determining the treatment options. Approximately 60–70% of FB impactions are located in the proximal esophagus at the level of the upper esophageal sphincter or thoracic inlet.5–7 The majority of FB impactions found in the upper or mid-esophagus will remain entrapped and require retrieval. Options for retrieval include nonemergent endoscopy (rigid or flexible) (Fig. 11-5) and Foley balloon extraction with fluoroscopy (Fig. 11-6). The Foley balloon extraction technique should be limited to round, smooth objects that have been impacted for less than one week in appropriately selected children without any evidence of complications.8 This technique has been shown to have a success rate of 80% while significantly lowering costs. Objects that are impacted in the lower esophagus often spontaneously pass into the stomach. For this reason, certain lower esophageal impactions may be observed for a brief duration of time, or attempted to be advanced into the stomach with bougienage or a nasogastric tube in the emergency department without anesthesia.9 Rarely, a chronic esophageal coin can cause esophageal perforation, but this will usually be contained (Fig. 11-7).

FIGURE 11-5 This coin was lodged in the esophagus of a 2-year-old child. It was unclear how long the coin had been in the esophagus. Rigid esophagoscopy was performed. (A) The coin is seen through the esophagoscope. (B) The optical graspers are being used to grasp the coin and remove it. The safety and success rate for rigid esophagoscopy and coin removal approaches 100% with minimal complications. This is usually a safe and successful way to remove a coin in the esophagus of children in whom the Foley catheter technique is not appropriate.

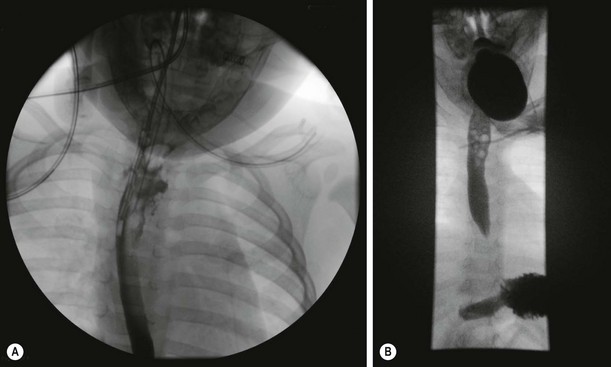

FIGURE 11-6 This radiograph shows the Foley catheter technique for removing a coin lodged in the upper esophagus. Under fluoroscopy, the Foley catheter is advanced past the coin and the balloon is filled with barium (asterisk). Under fluoroscopy, the catheter is then removed, bringing the coin with it. Care must be taken to ensure the patient does not aspirate the coin during its removal. This is a very cost-efficient way to remove coins in the upper esophagus in young children.

FIGURE 11-7 (A) This child was found to have an esophageal leak after uneventful extraction of a coin. (B) As the leak appeared to be contained, the patient was managed conservatively, and a repeat study two weeks later showed no evidence of a leak. A central line was placed for total parenteral nutrition.

Gastrointestinal Foreign Bodies

FB ingestions that are found to be distal to the esophagus are usually asymptomatic when discovered. Signs and symptoms including significant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fevers, abdominal distention, or peritonitis should alert the provider to potential complications including obstruction and/or perforation. The majority of FBs that pass into the stomach will usually pass through the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract uneventfully. These patients can be managed as an outpatient. Occasionally, a FB will remain present in the bowel after a period of observation and serial radiographs (Fig. 11-8). Prokinetic agents and cathartics have not been found to improve gut transit time and passage of the FB.10 Often parents are instructed to strain the child’s stool; however, in up to 50% of cases, the FB is not identified even with successful passage.5,11 If the child remains asymptomatic and the FB has not been identified, a repeat abdominal radiograph can be performed at two to three week intervals. Subsequent endoscopy is usually deferred for four to six weeks. Rarely, a chronic esophageal coin can cause esophageal perforation, but this will usually be contained (Fig. 11-8).

FIGURE 11-8 This child began to complain of abdominal pain and the (A) plain film was obtained. Due to the fact that it was unclear how long ago the sewing needle was ingested and because she was exhibiting new symptoms, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. (B) At laparoscopy, the sewing needle was seen to have penetrated the proximal jejunum and (C) was able to be extracted. A water soluble contrast study was performed a few days later. The study was unremarkable, her diet was advanced, and she recovered uneventfully.

Special Topic Ingestions

Batteries

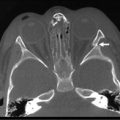

Battery ingestions deserve special attention due to the potential for significant morbidity associated with esophageal battery impactions. Button batteries are more commonly ingested than cylindrical batteries in young children.12 Symptoms occur in less than 10% of cases.12 Button batteries will appear as a round, smooth object on radiographs and are often misdiagnosed as coins. However, on close inspection, some larger button batteries will demonstrate a double contour rim (Fig. 11-9).

FIGURE 11-9 This child presented within 12 hours of swallowing an unknown foreign body. However, the double contour rim raised suspicion of ingestion of a button battery. This was confirmed upon emergency removal of the battery via rigid esophagoscopy.

Esophageal batteries are associated with increased morbidity due to the tissue injury that can occur through pressure necrosis, release of a low voltage electric current, or leakage of an alkali solution, which causes a liquefaction necrosis.11 This mucosal injury may occur in as little as one hour of contact time and may continue even after removal. Therefore, any suspected case of esophageal battery impaction warrants immediate removal. Following removal, an intraoperative esophagram may need to be considered. Early and late complications of esophageal battery impaction include esophageal perforation, tracheoesophageal fistula (Fig. 11-10), stricture and stenosis, and death.

FIGURE 11-10 This infant accidentally swallowed a lithium battery. The battery was removed within a few hours of its ingestion. However, 1 week later, the patient developed respiratory distress and bronchoscopy revealed this tracheoesophageal fistula (arrow).

If the battery is confirmed to be distal to the esophagus in the gastrointestinal tract, then it may be observed, similar to other gastrointestinal foreign bodies. More than 80% of batteries that are distal to the esophagus will pass uneventfully within 48 hours.2,12

Magnets

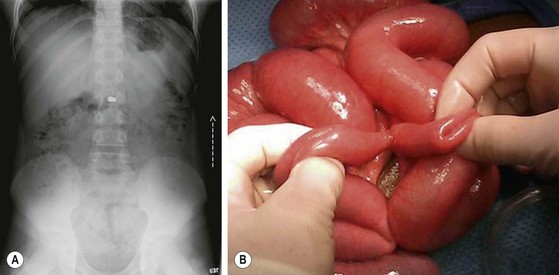

Magnet ingestion can be another source of significant morbidity when multiple magnets or a single magnet and a second metallic FB are ingested simultaneously, or within a short time of each other. These patients may also be asymptomatic when the FB is discovered, often with a plain radiograph taken for another reason. Radiographs should be interpreted with caution because multiple magnets may appear to be attached at a single point in the gastrointestinal lumen when, in fact, they are really attached across the bowel wall from two different intestinal lumens (Fig. 11-11A). Therefore, once the ingestion is confirmed on radiographs, close observation for potential complications is important.

FIGURE 11-11 This 11-year-old child swallowed two small magnets 24 hours prior to presentation to the emergency department. (A) The abdominal radiograph demonstrates an inability to detect if the two magnets are within a single intestinal lumen or attached across the bowel wall in two separate lumens. (B) This child underwent exploratory laparotomy for obstructive signs. The two magnets were found to be in two separate bowel lumens causing the bowel obstruction and fistulization between the two intestinal segments.

If the magnet is identified in the esophagus or stomach, endoscopy should be performed to prevent potential subsequent complications. Once the objects pass distal to the stomach, if separated within the gastrointestinal tract, they may attach to each other and lead to an obstruction, volvulus, perforation, or fistulization through pressure necrosis (Fig. 11-11B). Therefore, these children should be observed as an inpatient with serial abdominal exams and radiographs. At any time if the child becomes symptomatic, develops signs of obstruction on abdominal radiograph, or shows failure of the objects to progress in greater than 24 hours, then intervention is warranted.

Sharp Foreign Bodies

Ingestion of sharp foreign bodies can cause significant morbidity with an associated 15–35% risk of perforation.5 Commonly ingested objects include nails, needles, screws, toothpicks, safety pins, and bones. Perforation is most likely to occur in narrowed portions or areas of curvature in the alimentary tract, especially the ileocecal valve. Smaller objects and straight pins are associated with lower rates of perforation and can be conservatively managed.5 However, other objects should be retrieved endoscopically if possible or observed closely for potential development of complications.

Bezoars

A bezoar is a tight collection of undigested material that may often present as a gastric outlet or intestinal obstruction. These can include lactobezoars, phytobezoars, or trichobezoars. Presenting symptoms often include nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and abdominal distention. The diagnosis may be confirmed on plain radiographs, upper gastrointestinal contrast studies, or endoscopy. Often due to the size and density of the bezoar, medical management and endoscopic removal are unsuccessful, and operation is necessary (Fig. 11-12). See Chapter 29 for more information about bezoars.

Airway Foreign Bodies

Most episodes of aspirated FBs occur while eating or playing. Proposed explanations include the fact that young children are still in the oral exploration phase of development when everything tends to go into the mouth. Additionally, children often will cry or run with objects in their mouth. Overall, these young patients tend to have immature coordination of swallowing and less developed airway protection. The average age for fatal events is 15 months, and 75% of aspiration events occur in those less than 4 years.13 A high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis in these young children and especially in those who are debilitated. The annual death rates from aspiration of foreign bodies range from 350–2000 in the USA.13

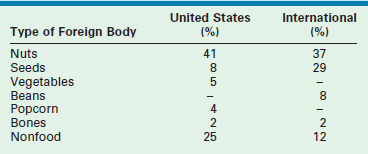

Boys are affected twice as often as girls. Like esophageal FBs, geographical differences have been noted (Table 11-1). For example, sunflower seeds are the most common seed aspirated in the USA, yet watermelon seeds are much more common internationally.14 A recent publication of 132 cases noted a high incidence of food aspirations, especially nuts, in children from non-English speaking backgrounds.15 Therefore, there may be a role for public education in targeted communities. Victims of child abuse represent another community that is at higher risk. Caregivers should be on alert when tending to a young child with multiple FBs or multiple episodes of aspiration.16,17

TABLE 11-1

Commonly Aspirated Foreign Bodies in Pediatric Patients (1968–2010)

Adapted from Kaushal, P, Brown D, Lander L, et al. Aspirated foreign bodies in pediatric patients, 1968–2010: A comparison between the United States and other countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011;75:1322–6.

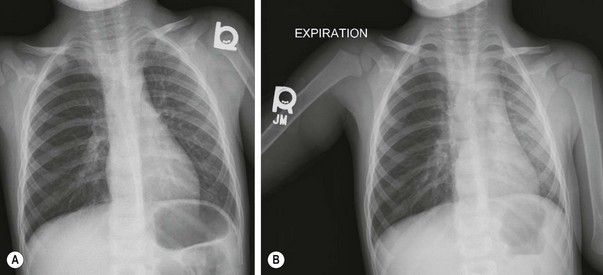

Following a detailed history, investigation usually turns to AP and lateral films of the neck and chest. If the child is cooperative, inspiratory and expiratory films are beneficial (Fig. 11-13). Review of the radiograph may reveal hyperinflation or ‘air trapping’ in up to 60% of children as the FB is acting as a one-way valve producing obstructive emphysema.18 In time, mediastinal shift may develop. Decubitus views may also prove helpful since the obstructed lung will not deflate, even while in a dependent position. Interestingly, up to 56% of patients may have a normal chest film within 24 hours of aspiration.19 Radiopaque foreign bodies are easily identified (Fig. 11-14A), but radiolucent FBs become clinically diagnosed through indirect radiographically clues such as hyperexpansion. Foreign bodies lodged in the larynx or trachea tend to have a higher radiographic detection rate (90%) than those in the bronchus (70%).18–22 A multi-institutional review of 1269 FB events revealed that 85% were correctly diagnosed following a single physician encounter.23 Therefore, a negative bronchoscopy rate of 10–15% is considered acceptable in order to avoid a delay in treatment with subsequent morbidity.24 Radiographic imaging remains helpful in children with a history of choking, yet definitive diagnosis still requires bronchoscopy.

FIGURE 11-13 (A) The anteroposterior chest radiograph shows slight hyperexpansion of the right lung in a four year old who aspirated a peanut. (B) On the expiratory film, note the increased lucency of the right lung compared to the left. This hyper-lucency on the right is due to air trapping from obstruction of the right main stem bronchus.

FIGURE 11-14 (A) This young child accidentally aspirated this nail which was found to be in the left main stem bronchus on chest radiography. (B) At bronchoscopy, with the bronchoscope in the trachea, the nail is seen to be peering out of the left main stem bronchus. (C) The nail was removed, and the child recovered uneventfully. Note the size of the nail relative to the child’s face and mouth.

Emergent management of airway FBs can be a dramatic experience. An accurate history remains important, yet sometimes is hard to obtain from small children who are unreliable historians. The use of the flexible bronchoscope to diagnose a FB followed by a rigid bronchoscopy for removal is a common approach utilized by pediatric surgeons. General anesthesia in the operating room using spontaneous ventilation offers the best chance for safe and successful removal. Positive pressure ventilation may be required, but this technique runs the risk for further propagating the FB into the more distal passages of the airway. With severely ill children, where transportation presents a logistical risk, rigid bronchoscopy has been performed safely in the intensive care setting.25

Bronchoscopy

We recommend positioning the head in the ‘sniffing’ position with a folded towel under the shoulders. The eyes are taped and protected. Precautions to minimize secretions, laryngospasm, and hypoxia are employed. Careful laryngoscopy may reveal a FB that can be retrieved with McGill forceps. More distal evaluation requires direct instrumentation of the airway. Special precautions must be considered to avoid injuries to the lips, tongue, and most importantly the teeth. Once the bronchoscopy starts, the operative team must be ready for emergent intubation, or rarely, tracheostomy. Liberal use of lidocaine (4 mg/kg) applied to the glottic area may minimize laryngospasm.

There are several commercial available rigid bronchoscopes. Instruments vary in size between 2.5 cm × 20 cm and 6 × 30 cm. Length and diameter of the bronchoscope will be determined by the age and size of the child. The Doesel–Huzly bronchoscope with Hopkins rod-lens telescope or Holinger ventilating bronchoscope are commonly used. Exposure is excellent with both, and the caliber of the scope allows the FB to be retracted into the scope during removal, thereby decreasing the risk of inadvertently dropping the FB during extraction (Fig. 11-14B,C). Equipment combining optics and illumination while allowing the introduction of working forceps are favored in most children’s hospitals.

The larynx and cords are visualized and the bronchoscope is advanced to the right of the laryngoscope and into the trachea. Inspection of the right or left main stem bronchus can be facilitated by turning the head to the opposite side. Angled scopes are generally not needed. The operative side channel allows passage of suction and retrieval instruments as well as instillation of fluids to help clear a bloody airway. The ventilation side port allows continuous ventilation during the procedure. Loose connections from any of these sites can lead to hypoventilation. Furthermore, if ventilation is impaired, the telescope can be removed, leaving the unobstructed bronchoscope for ventilation. In difficult cases, especially with FBs lodged distal to the main bronchus, a Fogarty catheter may be helpful to wedge the FB between the bronchoscope and Fogarty balloon. Partial FB removal will at times be necessary, especially with chronic foreign bodies associated with significant bleeding or airway edema. Prior to the second endoscopy,26 the child’s condition can be optimized with inhaled epinephrine and intravenous corticosteroids.27,28

Flexible bronchoscopy remains an option, especially for diagnostic purposes. The standard pediatric flexible bronchoscope has a two way deflection tip with a range between 180–220° and a side port to allow passage of suction catheters and working instruments. Most newborns can breathe normally around this scope for brief periods of time. A face mask adapter can be used to reduce the risk of hypoxia. The ultrathin scope (‘noodle scope’) can be inserted through smaller caliber endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes while maintaining ventilation. However, these scopes have very limited, if any, working channels and suction capability. Overall complications of rigid or flexible endoscopy include bleeding from local inflammation, laryngospasm, pneumothorax, and hypoxia with the more serious complications being found in the youngest patients.29,30

A lack of experience, poor visualization, and inadequate instrumentation contribute to failure of a successful examination. Many of these cases are seen at night, and operating room personnel frequently struggle to find the required instruments. The surgeon performing the procedure must ensure that all of the needed instruments are in working order before the child is brought to the operating room. A preoperative ‘game plan’ between nursing, anesthesia, and surgical staff is also important. Bleeding that obscures visualization is common, and the introduction of a small suction catheter through the working channel may be helpful. In other cases, partial FB removal is recommended with a plan to return to the operating room the next day. Rarely a thoracotomy with bronchotomy or lobectomy is required. Following successful removal, attention to proper cleaning of the instruments is important, given that inadequate cleaning and storage may predispose to cracks in the equipment that could lead to bacterial contamination.31

Maintaining bronchoscopic skills remains necessary to effectively manage these difficult cases. Across undergraduate and graduate medical education, simulation continues to gain momentum. Several institutions have developed simulation courses for residents to improve psychomotor skills associated with airway FBs. Objectives include an understanding of the tracheobronchial anatomy, ability to adequately visualize the larynx with laryngoscopy, proficiency in rigid bronchoscopy, and familiarity with FB instrumentation. Of note, in one institution, success in assembling the needed instruments and completing assigned tasks increased after completing the course on average 81% and 43%, respectively.32 One would expect further development of simulation exercises to be useful for initial credentialing and continued proficiency for both trainees and faculty.

References

1. 2010 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 28th Annual Report.

2. Kay, M, Wyllie, R. Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005; 7:212–218.

3. Arana, A, Hauser, B, Hachimi-Idrissi, S, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2001; 160:468–472.

4. Watanabe, K, Kikuchi, T, Katori, Y, et al. The usefulness of computed tomography in the diagnosis of impacted fish bones in the oesophagus. J Laryngol Otol. 1998; 112:360–364.

5. Wahbeh, G, Wyllie, R, Kay, M. Foreign body ingestion in infants and children: Location, location, location. Clin Pediatr. 2002; 41:633–640.

6. Panieri, E, Bass, DH. The management of ingested foreign bodies in children—A review of 663 cases. Eur J Emerg Med. 1995; 2:83–87.

7. Macpherson, RI, Hill, JG, Othersen, HB, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in children: Diagnosis, treatment, and complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996; 166:919–924.

8. Little, DC, Shah, SR, St Peter, SD, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric population: Our first 500 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 41:914–918.

9. Louie, MC, Bradin, S. Foreign body ingestion and aspiration. Pediatr Rev. 2009; 30:295–301.

10. Macgregor, D, Ferguson, J. Foreign body ingestion in children: An audit of transit time. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998; 15:371–373.

11. Litovitz, T, Schmitz, BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: An analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics. 1992; 89:747–757.

12. Hesham A-Kader, H. Foreign body ingestion: Children like to put objects in their mouth. World J Pediatr. 2010; 6:301–310.

13. Cataneo, AJ, Cataneo, DC, Ruiz, RL, Jr. Management of tracheobronchial foreign body in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008; 24:151–156.

14. Kaushal, P, Brown, D, Lander, L, et al. Aspirated foreign bodies in pediatric patients, 1968–2010: A comparison between the United States and other countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011; 75:1322–1326.

15. Choroomi, S, Curotta, J. Foreign body aspiration and language spoken at home: 10 year review. J Laryngol Otol. 2011; 125:719–723.

16. Binder, L, Anderson, W. Pediatric gastrointestinal foreign body ingestions. Ann Emerg Med. 1984; 13:112–117.

17. Nolte, K. Esophageal foreign bodies as child abuse: Potential fatal mechanisms. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1993; 14:323–326.

18. Zerella, J, Dimler, M, McGill, L. Foreign body aspiration in children: Value of radiography and complications of bronchoscopy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:1651–1654.

19. Oguz, F, Citak, A, Unuvar, E, et al. Airway foreign body aspiration in children. Int J Pediatrc Otorhinolaryngol. 2000; 52:11–16.

20. Mu, L, He, P, Sun, D. Inhalation of foreign bodies in Chinese children: A review of 400 cases. Laryngoscope. 1991; 101:657–660.

21. Metrangelo, S, Monetti, C, Meneghini, L, et al. Eight years’ experience with foreign body aspiration in children: What is really important for timely diagnosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34:1229–1231.

22. Karakoc, F, Karadag, B, Akbenglioflu, C, et al. Foreign body aspiration: What is the outcome? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002; 34:30–36.

23. Reilly, J, Thompson, J, MacArthur, C, et al. Pediatric aerodigestive foreign body injuries are complications related to timeliness of diagnosis. Laryngoscope. 1997; 107:17–20.

24. Mantor, P, Tuggle, D, Tunell, W. An appropriate negative bronchoscopy rate in suspected foreign body aspiration. Am J Surg. 1989; 158:622–624.

25. Muntz, H. Therapeutic rigid bronchoscopy in the neonatal intensive care unit. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985; 94:462–465.

26. Ciftci, A, Bingol-Kologlu, M, Senocak, M, et al. Bronchoscopy for evaluation of foreign body aspiration in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38:1170–1176.

27. Ritter, F. Questionable methods of foreign body treatment. Ann Otol. 1974; 83:729–733.

28. Black, R, Johnson, D, Matlak, M. Bronchoscopic removal of aspirated foreign bodies in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1994; 29:682–684.

29. Nussbaum, E. Pediatric fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1995; 34:430–435.

30. Wain, JC. Rigid bronchoscopy: The value of a venerable procedure. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2001; 11:691–699.

31. Nicolai, T. Pediatric bronchoscopy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001; 31:150–164.

32. Jabbour, N, Reihsen, T, Sweet, R, et al. Psychomotor skills training in pediatric airway endoscopy simulation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011; 145:43–50.