Chapter 19 Ingested Foreign Objects and Food Bolus Impactions

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Ingested Foreign Object

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Ingested Foreign Object

Introduction

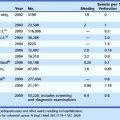

Ingested gastrointestinal (GI) foreign bodies and food bolus impactions occur frequently and are the second most common endoscopic emergency after GI bleeding. The actual incidence of foreign bodies and food impaction is unknown, and few controlled data exist on the management of foreign body ingestions. Although most GI foreign bodies do not result in serious clinical sequelae or mortality,1 it has been estimated that 1500 to 2750 patients die annually in the United States because of the ingestion of foreign bodies.2–4 More recent studies have suggested the mortality from GI foreign bodies to be significantly lower, with no deaths reported in more than 850 adults and one death in approximately 2200 children with a GI foreign body.5–11 As a result of the frequency of this problem and the rare but possible negative consequences, it is important for the gastroenterologist and endoscopist to understand the patients at risk for ingestion of foreign bodies, the best method for a prompt diagnosis, and the correct management with avoidance of unwanted complications.

Epidemiology

True foreign bodies may be the result of either unintentional or intentional ingestion. The most common patient group that unintentionally ingests foreign bodies is children. Of foreign body ingestions, 80% occur in children, with most occurring between the ages of 6 months and 3 years.12,13 Pediatric ingestions are almost always accidental, resulting from the child’s natural oral curiosity.14 The most common items ingested by children are coins followed by small toys, crayons, buttons, pins, jewels, nails, and disc batteries.6,9,10,15,16

Accidental ingestion in adults occurs in various groups of patients. Dentures and the presence of dental appliances are a common risk factor for accidental foreign body ingestion secondary to impaired tactile sensation during swallowing.17,18 A common occurrence is a patient mistakenly ingesting his or her own dentures.19 The other large patient group in which accidental ingestion of foreign bodies occurs includes individuals with compromised judgment or senses, such as very elderly, demented, or intoxicated individuals. Accidental coin ingestion has been encountered in young college students secondary to an increasingly popular beer drinking game, “Quarters,” where a quarter may inadvertently be swallowed and become lodged in the esophagus.20 Roofers, tailors, carpenters, and seamstresses have increased rates of foreign body ingestion because of accidental swallowing of nails or needles placed in the mouth during work. Intentional ingestion of foreign bodies is frequent in psychiatric patients or prisoners (Fig. 19.1).21,22 These patients ingest foreign bodies for a secondary gain and often have a history of previous foreign body ingestion, ingest multiple objects, and often ingest very complex objects.

Iatrogenic foreign bodies related to GI endoscopy procedures are becoming an increasing problem. Symptoms and complications have been reported as a result of capsule endoscopy; migrated esophageal, luminal, or biliary stents; and migrated gastrostomy buttons and catheters.23,24

Esophageal food impaction is a much more common problem than true foreign body ingestion with an estimated annual incidence of 13 to 16 episodes per 100,000 people.25 Most (75% to 100%) patients who present with a food impaction have some type of predisposing esophageal pathology.5,25–28 The most commonly observed abnormalities associated with food impaction are Schatzki rings or peptic strictures and, increasingly, eosinophilic esophagitis.29 Less commonly found as a predisposing cause are webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomoses, fundoplication wraps, and bariatric gastroplasties.30 Esophageal cancer very rarely manifests with acute food bolus impaction.31 Motility disorders such as achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, and nutcracker esophagus are infrequent causes of food impactions.32

Food impaction most commonly occurs in adults in their 4th or 5th decade but is becoming more prevalent in young adults because of the increasing incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis. The type of food impacted correlates with cultural and regional dietary habits. In the United States, hot dogs, pork, beef, and chicken are the most common foods resulting in impaction, whereas fish and fish bones are the most common food to result in impaction in Asian countries and coastal areas.33–35

Pathophysiology and Pathogenesis

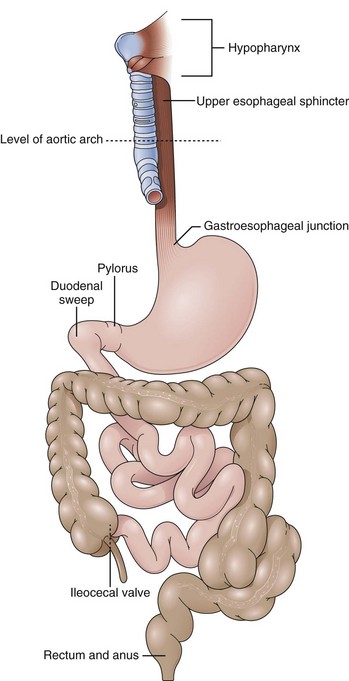

Most (80% to 90%) ingested foreign bodies and food bolus impactions pass spontaneously without clinical sequelae.1 However, 10% to 20% of GI foreign bodies require endoscopic intervention, and 1% may require surgical intervention.5,31,36 It is important to understand how ingested foreign bodies can result in significant disease, which patients are more likely to ingest complex foreign bodies, and in which parts of the GI tract foreign bodies are most likely to cause damage (Fig. 19.2). This understanding ensures appropriate use of endoscopic and surgical interventions.

The most common complications related to foreign bodies are obstruction and perforation, which can occur in any area of the GI tract where there is narrowing, angulation, anatomic sphincters, or previous surgery.37 The posterior hypopharynx is the first area of the GI tract in which a foreign body may become lodged, particularly small sharp objects such as chicken or fish bones.38,39 In the esophagus, there are four areas of physical narrowing where a food bolus or foreign body is likely to impact: the upper esophageal sphincter, the level of the aortic arch, the crossing of the main stem bronchus, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and gastroesophageal junction. All of these areas have been shown to be areas of true luminal narrowing with diameters of 23 mm or less in adult patients.40

Independent of the physiologic areas of narrowing, most food boluses are associated with esophageal pathology, including rings, webs, diverticula, and peptic strictures.2 Multiple esophageal rings associated with eosinophilic esophagitis have led to esophageal food impaction at much greater incandescence in young adults.41,42 Uncommonly, esophageal motor disturbances, such as achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, or segmental variations in peristalsis, may contribute to food and foreign body impactions.43–46

Foreign bodies and food impactions in the esophagus generally have the highest incidence of complications with the rate of complication being directly proportional to the time the object spends in the esophagus. Esophageal foreign bodies may lead to perforation, abscess, mediastinitis, pneumothorax, fistula formation, and cardiac tamponade.47,48 Once through the esophagus, most objects, including sharp objects, pass through the intestinal tract without consequence.1,37 However, among patients presenting with symptoms related to a foreign body, the perforation rate has been estimated to be 5% overall and up to 35% for sharp and pointed objects.31,49 Esophageal perforation is the most frequent cause of significant morbidity and mortality.47 The risk of perforation of the esophagus increases dramatically when foreign bodies or food boluses are left impacted in the esophagus for more than 24 hours. Other reported complications, including complications that have been reported to lead to fatalities, include GI bleeding, aortoenteric fistulas, aspiration, abscess formation, and true rarities such as perforation of the heart and lead and zinc toxicity.50–56

Once in the stomach, most foreign bodies pass through the GI tract without complications in 1 to 2 weeks. Exceptions are objects with a diameter of greater than 2 cm and objects longer than 5 cm, such as pencils, pens, and eating utensils, which have difficulty passing through the pylorus or the duodenal bulb and sweep.37,38,57 In the small intestine, three points of impedance exist where a foreign body may become lodged and result in obstruction: In the duodenal C-loop, long objects may get “hung up” and result in perforation. The narrowing and angulation of the ligament of Treitz can result in foreign body obstruction, and even smaller objects that were able to pass through the pylorus and ligament of Treitz may cause a distal small bowel obstruction by becoming impacted at the ileocecal valve. Patients with small bowel disease, history of adhesions, or partial small bowel obstructions may have greater difficulty passing foreign bodies through the small intestine.

Most objects, once in the small intestine and colon, do not cause damage. The bowel tends to protect itself naturally against foreign bodies. A foreign body stimulates peristalsis and axial flow in the small intestine, which results in the foreign body concentrated in the center of fecal residue with the blunt end leading and the sharp end trailing.58,59 As the foreign body travels further into the large intestine, it usually becomes centered in the lumen surrounded by stool, making a complication even less likely.2 Rectal foreign bodies rarely result from ingestion and more frequently are inserted into the rectum through the anus. However, occasionally an ingested foreign body may traverse the entire GI tract to the rectum before further passage is impaired by the rectal valves of Houston or the internal and external sphincters.

Clinical Features: History and Physical Examination

For adults who are able to communicate, a history of ingestion including timing, type of foreign body ingested, and onset of symptoms is usually reliable. History is particularly reliable for food impactions because patients are almost always symptomatic and can detail the exact onset of symptoms. Small sharp objects or fish bones often manifest with a foreign body sensation or odynophagia in the posterior pharynx or cervical esophagus; this occurs even if the foreign body has passed to the stomach because of a small mucosal laceration. Partial or complete esophageal obstruction almost always results in symptoms. Esophageal obstruction may cause substernal chest pain, dysphagia, gagging, vomiting, or a sensation of choking.60 More complete obstruction can lead to drooling and the inability to handle oral secretions.

The type of symptoms may aid in determining whether an esophageal foreign body is still present and where in the esophagus it may be located. If the patient presents with dysphagia, dysphonia, or odynophagia, there is almost an 80% chance that a foreign body or food impaction is present. If the symptom is retrosternal pain or a pharyngeal discomfort only, less than 50% of patients have an identifiable foreign object.61 The patient may be able to localize the object successfully in the posterior pharynx or at the level of the cricopharyngeal muscle. However, for objects located more distally in the esophagus and in the stomach, patient localization becomes poor with an accuracy of 30% to 40% in the esophagus and almost 0% in the stomach.62,63 Once in the stomach, small intestine, or colon, the only symptoms described would be secondary to a complication resulting from the foreign body, such as obstruction, perforation, or bleeding.

The history and symptoms for true foreign bodies are often less reliable than food impaction because true foreign bodies are often ingested by children, mentally impaired adults, or adults who have ingested the foreign body for secondary gain. Even with esophageal foreign bodies, 20% to 38% of children are asymptomatic.62,64 In children and adults unable to communicate, there may be no history of a foreign body ingestion from the patient or the caregiver in up to 40% of cases,65 necessitating a high degree of suspicion. Symptoms are more subtle and include drooling, poor feeding, blood-stained saliva, or a failure to thrive.65,66 Respiratory compromise may occur with aspiration or a proximally located esophageal foreign body that compresses the trachea causing wheezing and stridor.65,67

Diagnosis

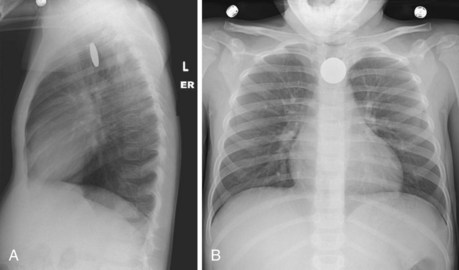

Diagnostic evaluation should begin with plain film radiographs. Patients with suspected foreign body ingestion should undergo anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the chest and abdomen to help determine the presence, type, and location of a foreign body.49 Anteroposterior and lateral neck and chest films are suggested if there is a suspicion of a foreign body in the esophagus versus the trachea or if there is a foreign object that may be obscured by overlying spine (Fig. 19.3).65,68 Plain films also aid in detecting complications such as aspiration, abdominal free air, or subcutaneous emphysema.60,69 Radiographic studies are more controversial in children. Because history from children is often poor, mouth-to-anus screening films have been advocated in suspected foreign body ingestions.49

Other authors have suggested a more directed approach or nonradiographic methods to determine the presence and location of foreign bodies in children.70 To limit radiation, hand-held metal detectors have been used with a sensitivity of greater than 95% for the detection and localization of metallic foreign bodies.71 Plain films are satisfactory in some cases of true foreign bodies and occasionally in cases of food ingestions with larger bones. Smaller bones or thin metal objects are not readily seen, however, and many objects, including plastic, wood, and glass, are not radiopaque.6 False-negative rates with plain films can be 47% and false-positive rates are close to 20% in the investigation of foreign bodies.61,72 Of films read by a nonradiologist for the presence of foreign bodies, 35% have been found to be misread.73 Generally, it is accepted that barium studies should not be performed in the evaluation of GI foreign bodies. If aspiration occurs, the hypertonic contrast agents used can cause acute pulmonary edema.74 Barium evaluation can delay a necessary therapeutic endoscopic procedure by interfering with endoscopic visualization and complicating removal of a foreign body.75

Advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may be used in unusual or difficult-to-diagnose cases and may aid in detecting soft tissue inflammation or the presence of an abscess. Three-dimensional CT has been used to diagnose foreign bodies not seen with other imaging and may aid in detecting complications of foreign body ingestion such as perforation or abscess before the use of endoscopy, and MR imaging may have a role in showing soft tissue periesophageal pathology.65,76,77

Diagnostic endoscopy provides the most accurate diagnostic modality in suspected ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Any patient with persistent symptoms and a continued clinical suspicion of a GI foreign body should undergo upper endoscopy even after negative or unrevealing radiographic evaluation.78 This approach ensures the correct diagnosis of food impactions, nonradiopaque objects, and radiopaque objects that are obscured by overlying bony structures.37 Endoscopy is the best method to detect underlying pathologic conditions, such as esophageal strictures, that contribute to a food impaction or foreign body that does not pass readily through the GI tract. Endoscopy also can closely examine the GI mucosa to assess for laceration or damage that may contribute to continuing symptoms after a foreign body has spontaneously passed. Most importantly, diagnostic endoscopy is directly linked to when endoscopy is used for therapy—treatment or extraction of a known or suspected foreign body. Diagnostic endoscopy is not indicated when small, blunt objects are known to have passed into the stomach and the patient is asymptomatic. These objects traverse the pylorus and the rest of the GI tract without complications. If a foreign body is known to have passed the ligament of Treitz, diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy would be of little added benefit. Rare exceptions are sharp objects that can be safely extracted with an enteroscope. More recently, double-balloon enteroscopes have been used for the retrieval of ingested foreign bodies and retained endoscopy capsules in the small bowel.79,80 Finally, diagnostic endoscopy is contraindicated when there is physical examination or radiographic evidence of a bowel perforation anywhere in the GI tract or a small bowel obstruction beyond the ligament of Treitz secondary to the foreign body.

Treatment

Of GI foreign bodies, 75% to 90% pass through the GI tract spontaneously without complication.5,81 Two more recent studies have emphasized conservative management with 86% to 97% of foreign bodies passing spontaneously with minimal complications.82,83 Esophageal foreign bodies were excluded from the above-mentioned studies. Although conservative management is successful in most nonesophageal foreign bodies, a more appropriate treatment plan if immediate endoscopy is not performed is to have a policy of expectant management and then selective endoscopy based on type, size, and location of the ingested object.84,85

Numerous medical therapies for esophageal foreign bodies or food impactions have been studied as primary treatment or in conjunction with endoscopic therapy. The most frequently used medication is glucagon, a smooth muscle relaxant that significantly reduces LES pressure with doses of 0.25 mg.86 Glucagon has treated esophageal food impactions successfully in 12% to 58% of cases.87–89 However, a randomized trial found glucagon no better than placebo in treating children with coins lodged in the esophagus.90 Glucagon is generally safe but may result in nausea, abdominal distention, and, rarely, vomiting. Glucagon would not work with a fixed obstruction present, which is often found with esophageal foreign bodies and food impactions. Glucagon does not provide definitive examination and treatment of coexisting esophageal pathology as does flexible endoscopy. Finally, glucagon may help when used with endoscopy by lowering LES pressure and facilitating the endoscope pushing a food impaction into the stomach.91 Nitroglycerin and nifedipine are other smooth muscle relaxants that have been anecdotally described as promoting passage of esophageal impactions into the stomach.49

Medical methods that have been described but should be avoided are gas-forming agents, emetics, and papain meat tenderizer. Gas-forming agents combined with a smooth muscle relaxant have been reported to have success rates of almost 70% in clearing esophageal foreign bodies into the stomach.92 However, esophageal rupture and perforation have occurred with these agents, particularly if there is a fixed obstruction or the foreign body has been present more than 6 hours.93,94 Papain, a meat tenderizer, and emetics for the treatment of food impaction are two methods that should never be used because of the risk of esophageal necrosis, perforation, and aspiration.2,95,96

The radiologic literature has multiple descriptions of methods to remove esophageal foreign bodies under fluoroscopic guidance. Reported methods include extraction with Foley balloon catheters, suction catheters, wire baskets, or a magnetic catheter to extract ferromagnetic metal objects.69,97 The largest experience has been with Foley catheters where the catheter is passed either nasally or orally into the esophagus and past the foreign body. The balloon is inflated and withdrawn to deliver the foreign body to the oropharynx where it can be retrieved. Although high success rates have been reported, the major drawback is loss of control of the foreign body, particularly at the level of the upper esophageal sphincter and laryngopharynx. Complications reported include nosebleeds, dislodgment of the foreign body in the nose, laryngospasm, vomiting, and, of largest concern, aspiration with resultant airway obstruction and death.98,99 Because radiologic methods do not match the efficacy or safety of endoscopy, few indications exist for their use. Radiologic methods to remove foreign bodies or food impactions should be limited to when endoscopy is unavailable or cannot be available within 12 to 24 hours.

Flexible endoscopy has become the diagnostic and therapeutic method of choice in both true GI foreign bodies and food boluses in pediatric and adult patients. This recommendation is based on multiple large series using endoscopy for the treatment of GI foreign bodies with success rates greater than 95% and associated morbidity and mortality reported at 0% in most studies but always less than 5%.5,9,25–27,75,100–103 Although treatment failures are rare, predictors of endoscopic failure and complications include intentional ingestion, ingestion of multiple complex foreign bodies, and lack of patient cooperation.49

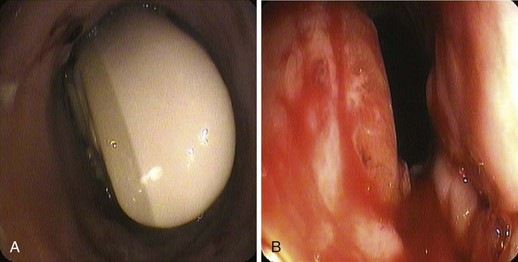

Because most GI foreign bodies pass through the GI tract uneventfully, the indication and timing for intervention with endoscopy is important. Generally, if a patient is symptomatic, intervention is required. For esophageal foreign bodies, this includes patients with odynophagia, dysphagia, vomiting, inability to handle secretions, drooling, chest pain, or the sensation of a present foreign body. Once past the esophagus, symptoms of obstruction or perforation may necessitate surgical rather than endoscopic intervention. If the patient is not overtly symptomatic or cannot accurately give a history concerning symptoms, the location and characteristics of the foreign body define the need for intervention. Generally, all esophageal foreign bodies and food impactions require intervention in an urgent or emergent fashion. No foreign body should be allowed to remain lodged in the esophagus longer than 24 hours. The time a foreign body is present in the esophagus is directly related to an increase in complications (Fig. 19.4).104,105

For most objects that reach the stomach, observation is acceptable because the risk of complications once the object is out of the esophagus is greatly diminished. Sharp objects are the primary exception and should be removed from the stomach and duodenum if they are within reach of the endoscope because the risk of perforation can be 15% to 35%.106 Objects longer than 5 cm and objects larger than 2 cm in diameter are unlikely to pass the duodenal sweep or pylorus, and attempts to remove them should be made. Observation is recommended for small blunt objects in the stomach, which almost always pass without complication. Even sharp or complex foreign bodies that fail endoscopic retrieval can initially be observed because only a few of these objects result in significant complications.82,83

In cases of more complex foreign bodies that are not extracted with the endoscope, periodical radiographs should be obtained to document progression through the GI tract. Close attention should be paid to symptoms such as fever, distention, vomiting, or abdominal pain that could suggest obstruction or perforation. For objects that are not extracted, the amount and timing of observation and radiographs should be individualized because transit time varies greatly based on patient and type of object ingested.107

Ensuring proper procedure, equipment, and patient preparation before initiating endoscopic therapy for foreign bodies and food boluses increases the success rate while maintaining a low complication rate. The endoscopist should be aware of the type of foreign bodies that may be encountered in that particular patient and the safest method to remove these objects. Before endoscopy, it is beneficial to perform a “dry run” on a similar object ex vivo5; this allows selection of a proper retrieval device and makes the extraction safer and easier. Table 19.1 lists endoscopes, endoscopic retrieval devices, and accessory equipment available to assist in removal of foreign bodies and food impactions. Before an attempt at removal of a complex foreign body, an endoscopy suite should be equipped with a minimum of a rat-tooth forceps, polypectomy snares, Dormier baskets, and retrieval nets.1,108 Standard size overtubes that extend past the upper esophageal sphincter and overtubes 45 to 60 cm in length that extend past the LES should be available. An overtube provides airway protection, allows frequent passes of the endoscope, and protects the mucosa from superficial and deep lacerations (Fig. 19.5).109 The longer overtube can aid in removing sharp objects and objects that cannot be pulled backward through the LES. A latex protector hood that can be simply attached to the end of the endoscope also helps prevent mucosal trauma in retrieval of sharp objects when overtubes are unavailable or when objects cannot easily be pulled through an overtube.110,111

Table 19.1 Equipment for Treatment and Removal of Gastrointestinal Foreign Bodies and Food Impactions

| Endoscopes | Overtubes | Accessory Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible endoscope | Standard esophageal overtube | Retrieval net |

| Rigid endoscope | 45–60 cm foreign body overtube | Alligator or rat-tooth forceps |

| Laryngoscope | Dormia basket | |

| Kelly or McGill forceps | Polypectomy snare | |

| Three-pronged grabber | ||

| Magnetic extractor | ||

| Steigmann-Goff variceal ligator cap | ||

| Latex protector hood |

The flexible endoscope is the preferred endoscopic method for treating GI foreign bodies and food impactions because of the high success rate, low complication rate, availability, patient comfort, affordability, and lack of need for general anesthesia.37,112 Rigid esophagoscopy has equal efficacy to flexible endoscopy in the treatment of esophageal foreign bodies but always requires general anesthesia, and few endoscopists have experience with the rigid endoscope.113 Flexible nasoendoscopes have been suggested as an alternative to standard flexible endoscopes but have been shown to have no additional benefit and may fail more frequently for foreign bodies below the cricopharyngeus.114 Laryngoscopes with the aid of a Kelly or McGill forceps should be available and may help in the removal of small sharp objects at the hypopharynx.

Finally, an ex vivo study has shown that success and speed of foreign body retrieval is directly related to endoscopist experience.109 For complex foreign bodies, the most experienced endoscopist at an institution should attempt endoscopic retrieval. If concern exists about experience with foreign body retrieval or a lack of necessary endoscopic equipment and accessories, the patient should be transferred to a tertiary care center for successful treatment and extraction of the foreign body.

Sharp Objects

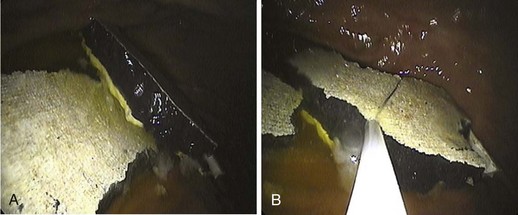

Sharp and pointed objects account for one-third of all perforations caused by GI foreign bodies; 15% to 35% of sharp and pointed foreign bodies left untreated may lead to a GI complication. Sharp objects, particularly toothpicks and animal bones, are the most likely to cause a perforation leading to the need for surgical management.115 Bones, toothpicks, and dental bridgework are the most common inadvertently swallowed sharp foreign bodies. More complex and varied pointed objects are seen in patients with psychiatric illnesses or incarcerated patients; common objects ingested include razor blades, pins, needles, nails, writing instruments, and metal wires (Fig. 19.6).

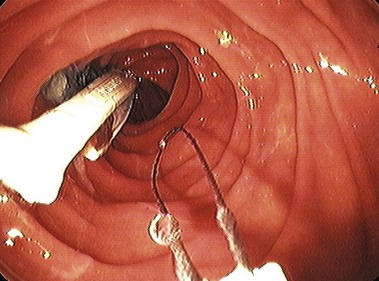

Sharp objects in the esophagus should be addressed in an emergent fashion with an attempt to remove the object within at least 24 hours. Because of the risk of perforation, attempts should be made to retrieve any sharp object within the reach of the endoscope. When removing sharp ingested foreign bodies Jackson’s axiom should be remembered: “advancing points puncture, trailing points do not.”116 When removing sharp objects, the foreign body should be grasped in a position so that the sharp or pointed end trails distally to the endoscope, reducing the chance of a significant procedure-related perforation or mucosal trauma during extraction.![]()

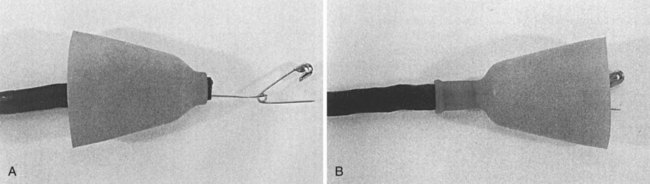

Polypectomy snares and foreign body retrieval forceps such as a rat-tooth or alligator forceps are the most commonly used devices for removing sharp foreign bodies with the most endoscopic control. If the size and shape of the foreign body prohibit easy withdrawal of the object, a standard-size overtube or a foreign body overtube (45 to 60 cm) should be used to protect the esophagus, airway, and oropharynx.111 An alternative is a soft latex protector hood that provides mucosal protection. The hood is simply placed and sometimes tied to the end of the endoscope with suture and folded back on itself to obtain endoscopic visualization. The foreign body is grasped, and as it is pulled through the LES or upper esophageal sphincter, the hood flips over the end of the endoscope and the tightly grasped foreign body, which is protected within the hood (Fig. 19.7). Hoods are commercially available, or alternatively a modified latex glove has been described to be used with similar methodology for the removal of sharp gastric foreign bodies.117

Coins, Button Batteries, and Magnets

The preferred retrieval device for coins is a retrieval net, which allows easy snaring of the coin and additionally protects the airway as the coin is pulled past the larynx.109 Retrieval with a net can be performed by directly snaring the coin in the esophagus and then pulling out the endoscope, net, and coin in toto. Alternatively, if there is no resistance, the coin can be gently pushed into the stomach and then more easily secured and retrieved by the net and subsequently removed via the mouth. Objects 2.5 cm or less can pass through the pylorus; this includes all coins except half dollars (30 mm) or silver dollars (38 mm). Once a coin enters the stomach, observation with conservative management is sufficient in most patients.118 Patients may maintain a regular diet, but if the coin does not pass in approximately 4 weeks or if more than one coin has been ingested, endoscopic removal is indicated.118,119

Button batteries are of special concern because they may contain an alkaline solution that can rapidly cause a liquefaction necrosis of esophageal tissue resulting in perforation or fistula formation. Ingested button batteries become symptomatic in 10% of cases, with children younger than 5 years being the most common patients.120 The mechanisms of injury include direct corrosive action, low-voltage burns, and pressure necrosis.5 Any clinical suspicion or radiographic evidence of a disc battery localized in the esophagus should lead to emergent endoscopy. In the retrieval of button disc batteries, it is crucial to protect the airway with endotracheal tube intubation in young children or an overtube in adults or older children.

Traditionally, a high endoscopic failure rate of up to 60% was associated with cases of button battery ingestion because the shape and contour made it difficult to grasp.121 The use of the Roth retrieval net has solved this problem making retrieval of button batteries successful in almost all cases. The battery can be retrieved from the esophagus or pushed into the stomach and retrieved. A stone retrieval basket also works with a high success rate but slightly less control than a retrieval net. Once in the stomach and beyond, button batteries rarely cause problems and are generally treated with observation.122 Of batteries that reach the duodenal sweep, 85% pass through the GI tract within 72 hours.123 Batteries located beyond the esophagus require endoscopy if the patient develops symptoms or the battery remains in the stomach for 48 hours on repeat radiograph.96

Ingested magnets within the reach of the endoscope should also be removed on an urgent basis. Single magnets rarely cause symptoms. However, concern should exist if multiple magnets were ingested or if magnets were ingested with other metal objects. These scenarios can lead to transmural magnetic attraction with subsequent pressure necrosis, fistula formation, and bowel perforation.124,125 Magnets can be removed with rat-tooth forceps, retrieval nets, or wire baskets. Using metal retrieval devices that attract the magnet may also make it easier to remove the magnets.

Narcotic Packets

Ingested narcotic packets are found in two types of patients—the “body stuffer” and the “body packer.” The body stuffer is a user or dealer who “stuffs” varying amounts of drugs into often poorly made packets before ingesting them to avoid arrest. The “body packer,” in the process of smuggling drugs, “packs” much larger amounts of drugs into carefully prepared, usually latex or plastic, packages that are designed to withstand GI tract transit.126,127 Diagnosis is usually made because of an arrest and confession by the patient.

Patients may present with intestinal obstruction or experience toxic effects of the drugs they have ingested. Up to 26% of patients who have ingested narcotic packets may have symptoms related to the narcotic ingested with serious symptoms including death in almost 5%.128 Toxicology screens may identify the drug, detect leakage, and allow the correct reversal agent to be administered. Abdominal radiographs and CT scans of patients with ingested narcotic packets show multiple round or sausage-shaped radiopacities, but false-negative imaging is well described.127–129 Endoscopy for removal of narcotic packets is contraindicated because of the danger of rupture of the package resulting in a toxicologic emergency.1 Observation with a clear liquid diet is recommended; lavage and purgatives are best avoided because of the risk of the rupture. Surgery is indicated for failure of the packets to progress, intestinal obstruction, and occasionally acute rupture.37

Food Bolus Impaction

Esophageal food bolus impaction is the most common “foreign body” in adults that can cause symptoms and require endoscopic intervention. In the United States, the most common impacted foods are meat products such as beef, chicken, pork, and hot dogs (Fig. 19.8).30,31 Food impaction may occur in association with alcohol ingestion, during which the patient may not chew food as carefully, leading to the terms “steakhouse syndrome” and “backyard barbecue syndrome.” In Asia and coastal areas, the most common food foreign bodies are fish bones. Fish bones rarely cause food impaction but cause symptoms because of the sharp and pointed ends of bones.

Food boluses may pass spontaneously; endoscopic intervention needs to be based on symptoms. If there is evidence of near or complete obstruction with the patient unable to handle secretions, salivating, or drooling, endoscopy should be performed on an urgent basis. If the patient has the sensation of the food bolus passing either spontaneously or after preendoscopy glucagon, a gentle trial of fluids then solids may be sufficient, and endoscopy can be avoided. However, if there is any concern that the food bolus remains, endoscopy should be performed because all esophageal food impactions should be removed in 24 hours owing to increased complications, with ideal removal in the first 6 to 12 hours after the onset of symptoms.1,130,131

Endoscopy is indicated because of the high esophageal-related pathology associated with food impactions. The accepted first endoscopic method used for the treatment of esophageal food impactions is the “push technique” with success rates greater than 90% and minimal complications.27 This technique entails gently pushing the esophageal food bolus into the stomach with the endoscope. Before pushing the food bolus into the stomach, an attempt should be made to steer the endoscope around the impaction and into the stomach; this allows assessment of the nature and degree of any obstructive esophageal pathology beyond the food bolus. Generally, if an endoscope can be advanced around a food bolus and past any obstruction, the push technique should be successful. After steering around the food bolus, the endoscope is pulled back proximal to the food impaction, and the impaction is gently pushed forward. This movement is aided by esophageal muscle relaxation induced by sedation, expansion of the esophageal lumen with endoscopic air-insufflation, and intravenous glucagon if it has been given.49

Even if the endoscope cannot be initially maneuvered around the impaction, a trial of gently pushing the food bolus can be safely attempted. Forcefully pushing the endoscope or blindly advancing dilators or retrieval devices past the food bolus is not recommended, however, because of the high percentage of patients with esophageal pathology.1,49 For larger food impactions, particularly meats such as chicken or beef that can be broken apart, the push technique can be performed after breaking the bolus into smaller pieces with a forceps or snare. With the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis, extra care should be taken pushing food through the esophagus because of the potential increased chance of perforation and mucosal tears.132 However, more recent studies have suggested that food impaction in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis can be treated effectively and safely with the push method.29

Certain food impactions cannot be safely pushed into the stomach and must be retrieved with the endoscope via the mouth. An overtube is useful to protect the airway and allow multiple passes of the endoscope. This approach is particularly useful in meat impactions in which the bolus shreds and breaks into multiple pieces before it can be completely removed. Standard endoscopic grasping forceps, snares, and baskets used under direct visualization can be employed alone or together. The Roth retrieval net can be particularly useful in managing food impactions because the food bolus can be contained completely within the net avoiding the use of an overtube and minimizing the risk of aspiration.133 For well-impacted food boluses, a Steigmann-Goff endoscopic ligator can be used to suction up large pieces of food that can be removed via the mouth.134,135

Greater than 75% of patients with food impactions are found to have esophageal pathology at the time of the index or follow-up endoscopy.5,25,27 More than half of patients with food bolus impactions have abnormal 24-hour pH studies, and almost half have abnormal esophageal manometry tests.28 In most patients, if a benign stricture or Schatzki ring is visualized after clearance of the food bolus, the narrowing can be effectively and safely dilated during the same endoscopy. If multiple esophageal rings are present, biopsy specimens should be obtained to evaluate for eosinophilic esophagitis, but dilation should generally be avoided.

Colorectal Foreign Bodies

If the object is in the distal rectum and is blunt and small, manual removal should be attempted. The ability to palpate the foreign body on rectal examination increases the chance that it can be removed successfully with manual extraction. Conscious sedation is usually adequate for manual removal, but in some cases general anesthesia may be needed to allow greater anal sphincter relaxation and ensure removal. Objects that are more proximally located and sharp or pointed objects should be removed under direct visualization with the use of a rigid proctoscope or flexible sigmoidoscope.110 Standard retrieval devices can be used to remove the object from the rectum. A latex hood or overtube can be particularly useful in removing longer and sharp objects to protect the rectal mucosa from laceration and to overcome the tendency of the anal sphincter to contract on removal of objects. Although conscious sedation often facilitates removal, general anesthesia can allow maximum dilation of the anal sphincter and allow removal of longer, more complex objects.111 Surgery is indicated for any complications secondary to a rectal or colon foreign body, including perforation, abscess, and obstruction, and may be more likely required when the object is proximal to the rectum.112

Postoperative Care

For uncomplicated removal of true foreign bodies or food bolus impactions, postoperative care should be no different than care after standard endoscopy. Each institution should follow its routine postprocedure recovery guidelines according to whether the procedure was performed under conscious sedation or general anesthesia. Most patients with foreign bodies and food impactions can be treated as outpatients. If the patient recovers without sequelae, the patient, family, or parents should observe the patient for any sign of complications in the next 24 hours. Patients with a food bolus impaction should be educated in methods of reducing further impactions, including eating more slowly, chewing foods thoroughly, and avoiding troublesome foods.49 Admitting certain patients for 24-hour observation postprocedure should be considered. These include young children, patients with multiple or complex foreign bodies, and patients in whom extraction and treatment of the foreign body was technically difficult.

A patient requires observation and further investigation if the extraction was difficult, if there was any evidence on endoscopy of a complication secondary to the foreign body or the endoscope, or if the patient shows signs of a complication postprocedure. The greatest concern is esophageal perforation, and the best outcomes and survival occur when this is recognized early.5 Any evidence of postprocedure fever, tachycardia, shortness of breath, chest or abdominal pain, or crepitus should lead to prompt plain films followed by contrast radiographic studies and surgical consultation.

Complications

The complication rate of endoscopic treatment of GI foreign bodies or food impactions ranges from no complications found in most studies to 1.8%.5,9,25,27,31,75,136 The most common complication associated with endoscopic removal of foreign bodies is esophageal perforation. Although no prospective data exist, patients with risk factors thought to increase the complication rate include uncooperative patients, patients with multiple ingestions, patients with deliberate ingestion such as prisoners or psychiatric patients, and patients with removal of sharp and pointed objects. Other complications reported with endoscopic removal of foreign bodies are GI bleeding, aspiration, and cardiopulmonary complications secondary to sedation. These complications do not occur at a rate significantly different than the complication rate found in standard upper GI endoscopy.

1 Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802-806.

2 Lyons MF, Tsuchida AM. Foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:1101-1114.

3 Clerf LH. Historical aspects of foreign bodies in the food and air passages. South Med J. 1975;68:1449-1454.

4 Devanesan J, Pisani A, Sharman P, et al. Metallic foreign bodies in the stomach. Arch Surg. 1977;112:664-665.

5 Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39-51.

6 Cheng W, Tam PKH. Foreign-body ingestion in children: Experience with 1265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1472-1476.

7 Chu KM, Choi HK, Tuen HH, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the use of the flexible gastroscope versus the bronchoscope in the management of foreign body ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:23-27.

8 Velitchkov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, et al. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract: Retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20:1001-1005.

9 Kim JK, Kim SS, Kim JI, et al. Management of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract: An analysis of 104 cases in children. Endoscopy. 1999;31:301-304.

10 Hachimi-Idrissi S, Corne L, Vandenplas Y. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood: Our experience and review of the literature. Eur J Emerg Med. 1998;5:319-323.

11 Paneiri E, Bass DH. The management of ingested foreign bodies in children—a review of 663 cases. Eur J Emerg Med. 1995;2:83-87.

12 Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:204-216.

13 Chen MK, Beierle EA. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Pediatr Ann. 2001;30:736-742.

14 O’Brien GC, Winter DC, Kirwan WO, et al. Ingested foreign bodies in the paediatric patient. Ir J Med Sci. 2001;170:100-102.

15 Arana A, Hauser B, Hachimi-Idrissi S, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:468-472.

16 O’Brien GC, Winter DC, Kirwan WO, et al. Ingested foreign bodies in the paediatric patient. Ir J Med Sci. 2001;170:100-102.

17 Gunn A. Intestinal perforation due to swallowed fish or meat bone. Lancet. 1966;1:125-128.

18 Bunker PG. The role of dentistry in problems of foreign body in the air and food passage. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;64:782-787.

19 Al-Wahadni A, Al Hamad KQ, Al-Tarawneh A. Foreign body ingestion and aspiration in dentistry: A review of the literature and reports of three cases. Dent Update. 2006;33:561-570.

20 Gluck M. Coin ingestion complicating a tavern game. West J Med. 1989;150:343-344.

21 O’Sullivan ST, Reardon CM, McGreal GT, et al. Deliberate ingestion of foreign bodies by institutionalized psychiatric hospital patients and prison inmates. Ir J Med Sci. 1996;165:294-296.

22 Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT. Gastrointestinal crosses: An indication for surgery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:310-314.

23 Perez Segura P, Siso I, Luque R, et al. Iatrogenic intestinal obstruction: A rare complication of capsule endoscopy in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy. 2007;39(Suppl 1):E298-E299.

24 Lattuneddu A, Farneti F, Lucci E, et al. Small bowel perforation after incomplete removal of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy catheter. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:2028-2031.

25 Longstreth GF, Longstreth KJ, Yao JF. Esophageal food impaction: epidemiology and therapy: A retrospective, observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:193-198.

26 Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, et al. Endoscopic techniques and management of foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A retrospective analysis of 139 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:784-789.

27 Vicari JJ, Johanson JF, Frakes JT. Outcomes of acute esophageal food impaction: Success of the push technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:178-181.

28 Lacy PD, Donnelly MJ, McGrath JP, et al. Acute food bolus impaction: Aetiology and management. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1158-1161.

29 Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356-361.

30 Weinstock LB, Shatz BA, Thyssen EP. Esophageal food bolus obstruction: evaluation of extraction and modified push technique in 75 cases. Endoscopy. 1999;31:421-425.

31 Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:208-210.

32 Breumelhof R, Van Wijk HJ, Van Es CD, et al. Food impaction in nutcracker esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1167-1171.

33 Lim CT, Quah RF, Loh LE. A prospective study of ingested foreign bodies in Singapore. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:96-101.

34 Ngan JHL, Fok PJ, Lai ECS, et al. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion: Experience of 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;211:459-462.

35 Lin HH, Lee SC, Chu HC, et al. Emergency endoscopic management of dietary foreign bodies in the esophagus. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:662-665.

36 Nandi P, Ong GB. Foreign body of the esophagus: Review of 2394 cases. Br J Surg. 1978;65:5-9.

37 Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33-38.

38 Stack LB, Munter DW. Foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:493-521.

39 O’Flynn P, Simp R. Fish bones and other foreign bodies. Clin Otolaryngol. 1993;18:231-233.

40 Bloom RR, Nakano PH, Gray SW, et al. Foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1986;10:618-621.

41 Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356-361.

42 Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795-801.

43 Rohl L, Aksglaede K, Funch-Jensen P, et al. Esophageal rings and strictures: Manometric characteristics in patients with food impaction. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:275-279.

44 McCord GS, Staiano A, Clouse RE. Achalasia, diffuse spasm, and non-specific motor disorders. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;5:307-335.

45 Tibbling L, Bjorkhoel A, Jansson E, et al. Effect of spasmolytic drugs on esophageal foreign bodies. Dysphagia. 1995;10:126-127.

46 Stein HJ, Schwizer W, DeMeester TR, et al. Foreign body entrapment in the esophagus of healthy subjects—a manometric and scintigraphic study. Dysphagia. 1992;7:220-225.

47 Brady P. Esophageal foreign bodies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:691-701.

48 Scher R, Tegtmeyer C, McLean W. Vascular injury following foreign body perforation of the esophagus: Review of the literature and report of a case. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:698.

49 Pfau PR, Ginsberg GG. Foreign bodies and bezoars, ed 7. Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, editors. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders. 2002:386-398.

50 Jiraki K. Aortoesophageal conduit due to a foreign body. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996;17:347-348.

51 Simic MA, Budakov BM. Fatal upper esophageal hemorrhage caused by a previously ingested chicken bone: Case report. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19:166-168.

52 Spitz L, Kimber C, Nguyen K, et al. Perforation of the heart by a swallowed open safety-pin in an infant. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:114-116.

53 Drnovsek V, Fontanez-Garcia D, Wakabayashi MN, et al. Gastrointestinal case of the day: Pyogenic liver abscess caused by perforation by a swallowed wooden toothpick. Radiographics. 1999;19:820-822.

54 Sevastos N, Rafailidis P, Kolokotronis K, et al. Primary aortojejunal fistula due to a foreign body: A rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:797-800.

55 McNutt TK, Chambers-Emerson J, Dethlefsen M, et al. Bite the bullet: Lead poisoning after ingestion of 206 lead bullets. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2001;43:288-289.

56 Bennett DR, Baird CJ, Chan KM, et al. Zinc toxicity following massive coin ingestion. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1997;18:148-153.

57 Koch H. Operative endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;24:65-68.

58 Davidhoff E, Towne JB. Ingested foreign bodies. N Y State Med J. 1975;75:1003-1007.

59 Ginsberg GG, Barkun AN, Bosco JJ, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:621.

60 Taylor RB. Esophageal foreign bodies. Emerg Clin North Amer. 1987;5:301-311.

61 Herranz-Gonzalez J, Martinez-Vidal J, Garcia-Sarandeses A, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:649-654.

62 Connolly AA, Birchall M, Walsh-Waring GP, et al. Ingested foreign bodies: Patient guided localization is a useful clinical tool. Clin Otolaryngol. 1992;17:520-524.

63 Lee J. Bezoars and foreign bodies of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1996;6:605-619.

64 Binder L, Anderson WA. Pediatric gastrointestinal foreign body ingestions. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:112-117.

65 Muniz AE, Joffe MD. Foreign bodies, ingested and inhaled. JAAPA. 1999;12:22-24.

66 Choudhurg CR, Bricknell MC, MacIver D. Oesophageal foreign body, an unusual cause of respiratory symptoms in a three week old baby. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:556-557.

67 Yoshida C, Peura D. Foreign bodies in the esophagus. In: Castell D, editor. The esophagus. Boston: Little, Brown; 1995:379-394.

68 Webb WA, Taylor MB. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. In: Taylor MB, editor. Gastrointestinal emergencies. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996:204-216.

69 Shaffer HA, de Lange EE. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies and strictures: Radiologic interventions. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1994;23:205-249.

70 Bassett KE, Schunk JE, Logan L. Localizing ingested coins with a metal detector. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:338-341.

71 Gooden EA, Forte V, Papsin B. Use of a commercially available metal detector for the localization of metallic foreign body ingestion in children. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:218-220.

72 Hodge D, Tecklenburg F, Fleischer G. Coin ingestion: Does every child need a radiograph? Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:443-446.

73 Jones NS, Lannigan FJ, Salama NY. Foreign bodies in the throat: A prospective study of 388 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:104-108.

74 Mosca S. Management and endoscopic techniques in cases of ingestion of foreign bodies. Endoscopy. 2000;32:232-233.

75 Mosca S, Manes G, Martino L, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Report on a series of 414 adult patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:692-696.

76 Takada M, Kashiwagi R, Sakane M, et al. 3D-CT diagnosis for ingested foreign bodies. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:192-193.

77 Silva RG, Ahluwaiia JP. Asymptomatic esophageal perforation after foreign body ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:615-619.

78 Ciriza C, Garcia L, Suarez P, et al. What predictive parameters best indicate the need for emergent gastrointestinal endoscopy after foreign body ingestion? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:23-28.

79 Neumann H, Fry LC, Rickes S, et al. A “double balloon enteroscopy worth the money”: Endoscopic removal of a coin lodged in the small bowel. Dig Dis. 2008;26:388-389.

80 Miehlke S, Tausche AK, Bruckner S, et al. Retrieval of two retained endoscopy capsules with retrograde double balloon enteroscopy in a patient with a history of complicated small-bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2007;39(Suppl 1):E157.

81 Velitchkov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, et al. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract: Retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20:1001-1005.

82 Kurkciyan I, Frossard M, Kettenbach J, et al. Conservative management of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34:173-177.

83 Weiland ST, Schurr MJ. Conservative management of ingested foreign bodies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:496-500.

84 O’Sullivan ST, McGreal GT, Reardon CM, et al. Selective endoscopy in management of ingested foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Is it safe? Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51:289-292.

85 Wong KKY, Fang CX, Tam PHK. Selective upper endoscopy for foreign body ingestion in children: An evaluation of management protocol after 282 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:2016-2018.

86 Colon V, Grade A, Pullman G, et al. Effect of doses of glucagon used to treat food impaction on esophageal motor function of normal subjects. Dysphagia. 1999;14:27-30.

87 Ferrucci JT, Long LA. Radiologic treatment of esophageal food impaction using intravenous glucagon. Radiology. 1977;125:25-28.

88 Trenker SW, Maglinte DT, Lehman G, et al. Esophageal food impaction: Treatment with glucagon. Radiology. 1983;149:401-403.

89 Al-Haddad M, Ward EM. Glucagon for the relief of esophageal food impaction: Does it really work? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1930-1933.

90 Mehta D, Attia M, Quintana E, et al. Glucagon use for esophageal coin dislodgment in children: A prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:200-203.

91 Alaradi O, Bartholomew M, Barkin JS. Upper endoscopy and glucagon: A new technique in the management of acute esophageal food impaction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:912-913.

92 Robbins MI, Shortsleeve MJ. Treatment of acute esophageal food impaction with glucagon, an effervescent agent, and water. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:325-328.

93 Kaszar-Seibert DJ, Korn WT, Bindman DJ, et al. Treatment of acute esophageal food impaction with a combination of glucagon, effervescent agent, and water. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:533-534.

94 Smith JC, Janower ML, Geiger AH. Use of glucagon and gas-forming agents in acute esophageal food impaction. Radiology. 1986;159:567-568.

95 Maini S, Rudralingam M, Zeitoun H, et al. Aspiration pneumonitis following papain enzyme treatment for oesophageal meat impaction. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:585-586.

96 Litovitz T, Scmitz BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: An analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics. 1992;89:747-757.

97 Paulson EK, Jaffe RB. Metallic foreign bodies in the stomach: Fluoroscopic removal with a magnetic orogastric tube. Radiology. 1990;174:191-194.

98 Hawkins DB. Removal of blunt foreign bodies from the esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:935-940.

99 Schunk JE, Harrison AM, Corneli HM, et al. Fluoroscopic Foley catheter removal of esophageal foreign bodies in children: Experience with 415 cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94:709-714.

100 Blair SR, Graeber GM, Cruzzavala JL, et al. Current management of esophageal impactions. Chest. 1993;104:1205-1209.

101 Thapa BR, Singh K, Dilawari JB. Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies from the gastrointestinal tract. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:1105-1110.

102 Khurana AK, Saraya A, Jain N, et al. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Trop Gastroenterol. 1998;19:32-33.

103 Conway WC, Sugawa C, Ono H, et al. Upper GI foreign body: An adult urban emergency hospital experience. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:455-460.

104 Bonadio WA, Emslander H, Milner D, et al. Esophageal mucosal changes in children with an acutely ingested coin lodged in the esophagus. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1994;10:333-334.

105 Chaikhouni A, Kratz JM, Crawford MA. Foreign bodies of the esophagus. Am Surg. 1985;51:173-179.

106 Henderson CT, Engel J, Schlesinger P. Foreign body ingestion: Review and suggested guidelines for management. Endoscopy. 1987;19:68-71.

107 Macgregor D, Ferguson J. Foreign body ingestion in children: An audit of transit time. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15:371-373.

108 Nelson DB, Bosco JJ, Curtis WD, et al. ASGE technology status evaluation report. Endoscopic retrieval devices. February 1999. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:932-934.

109 Faigel DO, Stotland BR, Kochman ML, et al. Device choice and experience level in endoscopic foreign object retrieval: An in vivo study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:490-492.

110 Bertoni G, Pacchione D, Sassatelli R, et al. A new protector device for safe endoscopic removal of sharp gastroesophageal foreign bodies in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:393-396.

111 Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Conigliaro R, et al. A simple latex protector hood for safe endoscopic removal of sharp-pointed gastroesophageal foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:458-461.

112 Gmeiner D, von Rahden BHA, Meco C, et al. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy for treatment of foreign body impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2026-2029.

113 Weissberg D, Refaely Y. Foreign bodies in the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1854-1857.

114 Chu KM, Choi HK, Tuen HH, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing the use of the flexible gastroscope versus the bronchoscope in the management of foreign body ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:23-27.

115 Rodriguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Sirvent JM, et al. Surgically treated perforations of the gastrointestinal tract caused by ingested foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:701-707.

116 Jackson C, Jackson CL. Diseases of the air and food passages of foreign body origin. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1937.

117 Kao LS, Nguyen T, Dominitz J, et al. Modification of a latex glove for the safe endoscopic removal of a sharp gastric foreign body. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:127-129.

118 Byrne WJ. Foreign bodies, bezoars, and caustic ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1994;4:99-119.

119 Rebhandl W, Milassin A, Brunner L, et al. In vitro study of ingested coins: Leave them or retrieve them? J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1729-1734.

120 Temple AR, Veltri JC. One year’s experience in a regional poison control center. The Intermountain Regional Poison Control Center. Clin Toxicol. 1978;12:27-89.

121 Litovitz TL. Button battery ingestions. JAMA. 1983;249:2495-2500.

122 Chan YL, Chang SS, Kao KL, et al. Button battery ingestion: An analysis of 25 cases. Chan Gung Med J. 2002;25:169-174.

123 Litovitz TL. Battery ingestions: Product accessibility and clinical course. Pediatrics. 1985;75:469-476.

124 Alzakem AM, Soundappan SSV, Jefferies H, et al. Ingested magnets and gastrointestinal complications. J Pediatr Child Health. 2007;40:497-498.

125 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Gastrointestinal injuries from magnet ingestion in children—United States, 2003–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1296-1300.

126 McCarron NM, Wood JD. The cocaine “body packer” syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 1983;250:1417-1420.

127 Caruna DS, Weinbach B, Goerg D, et al. Cocaine packer ingestion. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:73-74.

128 June R, Aks SE, Keys N, et al. Medical outcome of cocaine bodystuffers. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:221-224.

129 Eng JGH, Aks SE, Marcus C, et al. False-negative abdominal CT scan in a cocaine body stuffer. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:192-193.

130 Smith MT, Wong RKH. Foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:361-382.

131 Chaves DM, Ishioka S, Felix VN, et al. Removal of a foreign body from the upper gastrointestinal tract with a flexible endoscope: A prospective study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:887-892.

132 Gluck M, Schembre DB, Kozarek RA. A concern with the use of the push technique in patients with multiple esophageal rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:178-181.

133 Neustater B, Barkin JS. Extraction of an esophageal food impaction with a Roth retrieval net. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:66-67.

134 Mamel JJ, Weiss D, Pouagare M, et al. Endoscopic suction removal of food boluses from the upper gastrointestinal tract using Steigmann-Goff friction fit adapter: An improved method for removal of food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:593-596.

135 Pezzi JS, Shiau YF. A method for removing meat impactions from the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:634-636.

136 Classen M, Farthmann EF, Seifert E, et al. Operative and therapeutic techniques in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol. 1978;7:741-763.