16 Infraorbital hollow and nasojugal fold

Summary and Key Features

• The infraorbital hollow (IOH) refers to the U-shaped or curvilinear depression under the eyes and comprises the tear trough, nasojugal fold, and palpebromalar groove and has become a common presentation for those seeking cosmetic enhancement to the lower eyelid and mid-face

• With thin skin overlying bone and little to no subcutaneous fat or muscle in this region, the IOH can be an unforgiving region and challenging to treat with injectable agents

• Injections seem to work best in patients with thick and smooth skin and a well-defined tear trough, without excessively protruding eyelid fat or excess eyelid skin

• Hyaluronic acid is currently the injectable agent treatment of choice for IOHs and lower eyelid / periorbital augmentation

• Meticulous injection with small volumes, reduced volume speed, supraperiosteal placement, lower gauge needles and / or cannulas, and minimal number of injection sites will reduce the risk of complications

• Some patients are not suited to fillers alone and require adjuvant therapy or surgery for further restoration of the IOH

Introduction

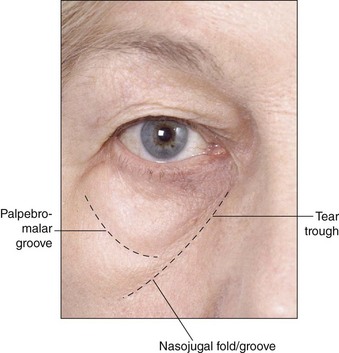

The infraorbital hollow (IOH) refers to the curvilinear or U-shaped depression under the eyes from the nasal bone to the outer corner of the eye and comprises three core elements: the ‘tear trough’ and nasojugal fold medially, and the palpebromalar groove laterally (Fig. 16.1). Although the terms ‘tear trough’ and ‘nasojugal fold’ have historically been used interchangeably, the former – which occurs mildly in all people across all ages – refers to the superior aspect of the latter. A sign of early aging, the deepening of the tear trough leads to a true indentation at the junction of the thin eyelid skin above and thicker skin of the cheek below. Later, the mid-cheek may descend, accentuating a flat or hollow crescent below the eye. The appearance of hollows and dark circles under the eye is the interplay of various factors. Genetics and habits / environmental exposures lead to dyschromias and pigmentation; soft tissue laxity, subcutaneous volume alterations, changes in bony landmarks, and redistribution of superficial fat all lead to shadowed contours and deepening folds. Periorbital volumetric shifting and loss is not an isolated event but part of a global shift in the contours of the aging face.

There is little to no superficial fat under the lower eyelid. The orbicularis oculi muscle has direct bony attachment for approximately one-third of the orbital rim length, from the nasal bone to the medial limbus. Laterally, orbicularis-retaining ligaments connect the deep surface of the skin to bone. Retaining ligaments weaken, facial bones recede, and volume decreases in the deep fat pads, causing the cheek to descend and superficial fat to accumulate under the eye, all of which combine with genetically predisposed discolorations and bony changes to produce the perception of hollowed and sometimes baggy eyes, deep and shadowed tear troughs, and an aged, fatigued appearance refractory to cosmetic attempts at concealment (Fig. 16.1).

Candidates for augmentation of the infraorbital hollow

Proper patient selection is critical and relies on careful ophthalmologic and medical history and physical assessment. Poor candidates are unlikely to obtain optimal results and may not be satisfied with results and are at higher risk of side effects, such as visibility and irregularity (Table 16.1). Patients with diseases or metabolic conditions that predispose to lower eyelid irregularity or bleeding and infection should be excluded, and all manner of anticoagulant medications and supplements discontinued if medically safe for at least 2 weeks prior to treatment. Some patients have genetically determined pigmentation that may look like a tear trough but without an indentation that can be filled. Pigmented dark lower eyelid circles cannot be improved by fillers and can, in fact, be worsened by treatment. Older patients with thinner, crepe-like, inelastic skin and individuals with pre-existing malar edema – whether metabolic (thyroid disease) or otherwise (i.e. chronic sinus disease, prior surgery, etc.) – may not respond well and also have an increased risk for adverse events and dissatisfaction with these treatments. Patients with orbital fat herniation and significant skin laxity would benefit first from lower lid blepharoplasty or other surgical procedures. Injection works best in patients with thicker and smooth skin and a well-defined tear trough or defined maxillary retrusion / hypoplasia (common in young Asian females), without excessively protruding eyelid fat or excess eyelid skin.

Table 16.1 Identifying candidates for augmentation of the infraorbital hollow

| Best candidates | Poor candidates |

|---|---|

| Young patients with good skin elasticity | Elderly patients with poor skin elasticity |

| Thick smooth skin | Very thin skin |

| Good skin tone | Transparent or dyspigmented skin |

| Minimal laxity | Significant skin laxity |

| Mild-to-moderate tear troughs | Extremely deep tear troughs |

Appropriate filling agents

The use of autologous fat had gained popularity in recent years (also) as a replacement for surgery for the correction of contour defects and has been used for augmentation of the IOH, but results have been generally unpredictable and often associated with considerable side effects such as lumpiness, long-lasting irregularities, volume distortion, and prolonged edema, as well as risks associated with any surgical procedure. More recently, hyaluronic acid (HA) – with its gel consistency, varying concentrations and the possibility of dilution with lidocaine or saline, favorable flow characteristics, fewer side effects, and non-permanence – has emerged as the treatment of choice for augmentation of the lower periorbita by injection. Lumps or irregularities can be avoided with careful and precise injection techniques and can also be reversed through treatment with hyaluronidase, an important consideration when injecting in delicate areas requiring precise placement of filling agent. Surprisingly, HA in the periorbital region yields better than expected longevity. Lambros (and others) have described the persistence of effect, often in excess of 1 year (see Ch. 15). Donath and colleagues used three-dimensional imaging in 20 patients treated in the tear trough with HA and found an average 85% maintenance of effect at the final follow-up visit (average 14.4 months); the patient with the longest duration retained 73% volume augmentation at 23 months without any touch-ups. Side effects with HA can include visibility and nodules, a bluish tint (from the presumed Tyndall effect), along with injection-related bruising and swelling (see Complications).

Augmentation techniques

Skin preparation, anesthetic, and syringes

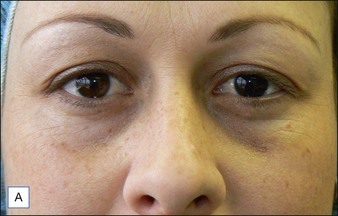

Patients are treated sitting in an upright position. Photographs should be taken with controlled lighting, which can illuminate rather than disguise the appearance of rhytides, tear trough deformity, and lower lid fat prolapse. After all makeup has been removed and skin thoroughly cleaned with alcohol, the patient is asked to look upward to accentuate and delineate the borders of the tear trough, and all areas of injection can be marked using a fine-tipped marker, including adjacent areas requiring augmentation (Fig. 16.2).

General techniques

Injections are deep in the suborbicularis plane at or below the orbital rim at the supraperiosteal level except in the medial aspect of the orbicularis oculi, which attaches to bone and requires direct injection. Superficial injections in the periorbital region increase the risk of visibility and skin discoloration secondary to the Tyndall effect (see Complications), although some researchers (such as Hirmand) have described the occasional need for very superficial subdermal injection using a 32-gauge needle for spot application over a 1–2 mm surface area to ‘lift’ the overlying skin.

Augmentation of the infraorbital hollow

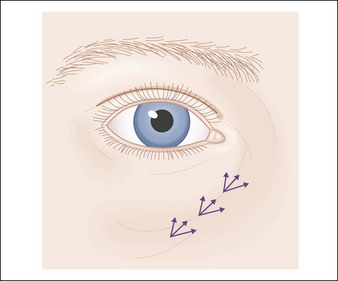

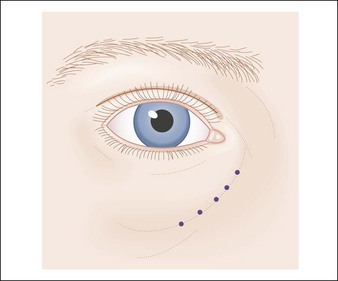

Linear threading (the fanning technique) (Fig. 16.3) and serial puncture (Fig. 16.4) are the most commonly used techniques in the IOH. Goldberg & Fiaschetti describe deep injection using multiple needle passes to layer and feather the filler in a three-dimensional pattern in the IOH and cheek. Morley & Malhotra used the serial puncture technique with three to eight injections along the inferior IOH, depositing small aliquots of filling agent. Hirsch and colleagues detail the use of 1-inch needles and two or three injection sites just above the periosteum to augment the lateral to medial IOH, using the push-ahead technique, in which the submuscular layer is dissected by the forward movement of the filling agent rather than the tip of the needle. Small aliquots of 0.1–0.2 mL are deposited along the length of the groove, using digital manipulation instead of frank injection in the medial portion to avoid inadvertent injection of the infratrochlear vessels and infraorbital nerve. Hirmand describes a similar technique of discontinuous deposition using a blunt cannula, three to five injections of 0.01–0.5 mL deep in the supraperiosteal plane in the medial aspect of the tear trough, with gentle digital massage to disperse the filler into the intended location. The vertical supraperiosteal depot technique, pioneered by Sattler (see Ch. 25), involves the vertical deposition of small aliquots of filling agent (0.02–0.5 mL) at the supraperiosteal level using a 90° angle, with injections placed 2–3 mm apart.

Complications

Ecchymosis and edema are the most common injection-related side effects. Ecchymosis may last up to 10 days, while edema can last for up to 3 weeks or more depending on the causality. Visible irregularities in patients with thin or lax skin can be massaged away over several weeks. Superficial injection increases the risk of lumps that are often difficult to resolve without injections of hyaluronidase to dissolve the implant (Fig. 16.5).

Too superficial injections can yield the appearance of a bluish-gray tint secondary to the Tyndall effect, in which the injected filler, readily visible under thin skin, causes preferential scattering of blue light (Fig. 16.6). Overcorrection may lead to unnatural bulges and festooning or a ‘baggy’ eyelid. It is critical to address other areas of deficit; undercorrection of the lateral orbit or mid-face will make the appearance of an augmented tear trough unappealing. Under- or overcorrection can be assessed at follow-up and treated appropriately.

Bellman B. Complication following suspected intra-arterial injection of Restylane. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2006;26:304–305.

Bosniak S, Sadick NS, Cantisano-Zilkha M, et al. The hyaluronic acid push technique for the nasojugal groove. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34:127–131.

Carruthers JD, Carruthers A. Facial sculpting and tissue augmentation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 pt 2):1604–1612.

Coleman SR. Avoidance of arterial occlusion from injection of soft tissue fillers. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2002;22:555.

Donath AS, Glasgold RA, Meier J, et al. Quantitative evaluation of volume augmentation in the tear trough with a hyaluronic acid-based filler: a three-dimensional analysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;125:1515–1522.

Donofrio LM. Technique of periorbital lipoaugmentation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:92–98.

Goldberg RA, Fiaschetti D. Filling the periorbital hollows with hyaluronic acid gel: initial experience with 244 injections. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;22:335–343.

Goldman MP. Superficial nodularity of hydroxylapatite filler to fill the infraorbital hollow. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:822–824.

Hevia O. A retrospective review of calcium hydroxylapatite for correction of volume loss in the infraorbital region. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:1487–1494.

Hirmand H. Anatomy and nonsurgical correction of the tear trough deformity. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;125:699–708.

Hirsch RJ, Narurkar V, Carruthers JD. Management of injected hyaluronic acid induced Tyndall effects. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2006;38:202–204.

Hirsch RJ, Carruthers JDA, Carruthers A. Infraorbital hollow treatment by dermal fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:1116–1119.

Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL, Carruthers JD. Successful management of an unusual presentation of impending necrosis following a hyaluronic acid injection embolus and proposed algorithm for management of hyaluronidase. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:357–360.

Lambros VS. Hyaluronic acid injections for correction of the tear trough deformity. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;120:745–805.

Lambros VS. Discussion: Quantitative evaluation of volume augmentation in the tear trough with a hyaluronic acid-based filler: a three-dimensional analysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;125:1523–1524.

Lowe NJ. Arterial embolization caused by injection of hyaluronic acid (Restylane). British Journal of Dermatology. 2003;148:379.

Morley AMS, Malhotra R. Use of hyaluronic acid filler for tear-trough rejuvenation as an alternative to lower eyelid surgery. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;27:69–73.

Pessa JE, Desvigne LD, Lambros VS, et al. Changes in ocular globe-to-orbital rim position with age: implications for aesthetic blepharoplasty of the lower eyelids. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 1999;23:337–342.

Roh MR, Chung KY. Infraorbital dark circles: definition, causes, and treatment options. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:1163–1171.

Rohrich RJ, Arbique GM, Wong C, et al. The anatomy of suborbicularis fat: implications for periorbital rejuvenation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124:946–951.

Sadick NS, Bosniak SL, Cantisano-Zilkha M, et al. Definition of the tear trough and the tear trough rating scale. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2007;6:218–222.

Saylan Z. Facial fillers and their complications. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2003;23:221–224.

Schanz W, Schippert W, Ultmer A, et al. Arterial embolization caused by injection of hyaluronic acid (Restylane). British Journal of Dermatology. 2002;146:928–929.