Chapter 21 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Early Lesions of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Crohn’s Disease

The earliest endoscopic lesions in Crohn’s disease are considered to be tiny punched-out ulcers in an otherwise normal-appearing mucosa. These tiny ulcers enlarge and aggregate to form larger surface ulcerations. Normal mucosa surrounds the ulcerations until late in the disease. Scanning electron microscopy has identified surface erosions of 100 to 200 µm surrounded by M cells, which may be the entry point for whatever the etiologic agent is found to be in Crohn’s disease.1

Importance of Assessing Extent of Disease

Establishing the extent of intestinal inflammation is essential in attempting to differentiate Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. This effort may be helpful to help guide medical therapy, to establish the risk of colorectal carcinoma, and to decide when to consider surgery. Colonoscopy with multiple biopsies is the standard for defining the extent of disease and excluding other forms of inflammation. Biopsies are more sensitive than macroscopic evaluation in determining the degree of inflammation and increase the diagnostic yield of an endoscopy considerably; biopsy specimens from macroscopically normal mucosa can reveal microscopic areas of inflammation. Skip lesions are suggestive of Crohn’s disease, whereas ulcerative colitis tends to be a more circumferential and contiguous disease. Biopsies of the terminal ileum are often crucial in the differentiation of Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. Involvement of the ileum is highly suggestive of Crohn’s disease. Proximal biopsy specimens often are revealing in a patient with resistant proctitis and a normal-appearing barium study. Proximal inflammation can be present in biopsy specimens in 50% of these patients. In addition, proximal biopsy specimens that are negative for inflammation identify patients with primarily rectal or left-sided colonic involvement; these patients usually respond to medicated suppositories or enemas, and evidence shows that the addition of topical therapy offers significant benefit for these patients.2

Assessing Disease Severity

Crohn’s Disease

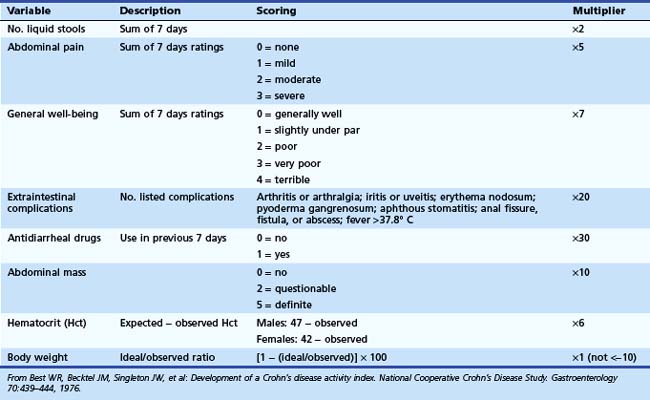

The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) was developed in 1976 by Best and coworkers3 as part of the National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. It is the “gold standard” index for any Crohn’s disease clinical trial. A multivariant regression analysis was performed, and eight variables were identified as predictors of disease activity: number of stools, abdominal pain, general well-being, extraintestinal complications, antidiarrheal agents used in the previous 7 days, abdominal mass felt on palpation, hematocrit, and body weight (Table 21.1). CDAI scores range from 0 to 600. A score of less than 150 corresponds to relative disease quiescence (remission); 150 to 219, mildly active disease; 220 to 450, moderately active disease; and greater than 450, severe disease. A decrease in greater than 100 points indicates a clinically significant improvement in disease activity (termed clinical response). Older literature suggests that a clinical response is defined by a decrease in CDAI by greater than 70 points. The limitations of the CDAI include the complexity of the calculation needed by the physician, the weight placed on subjective complaints such as general well-being and abdominal pain, and the requirement of the patient to keep a diary for 7 days.

The Harvey-Bradshaw Index,4 or the Simple Index, is less complicated than the CDAI and uses five variables recorded on one occasion (Table 21.2). No diary and no laboratory values are required. The five variables are general well-being, abdominal pain, abdominal mass, number of liquid stools, and systemic complications. Each variable is weighted the same. Studies have found that the Harvey-Bradshaw Index correlates well with the CDAI.5

| Variable | Scoring | Total |

|---|---|---|

| General well-being | 0 = very well | |

| 1 = slightly below par | ||

| 2 = poor | ||

| 3 = very poor | ||

| 4 = terrible | ||

| Abdominal pain | 0 = none | |

| 1 = mild | ||

| 2 = moderate | ||

| 3 = severe | ||

| No. liquid stools daily | — | |

| Abdominal mass | 0 = no | |

| 1 = dubious | ||

| 2 = definite | ||

| 3 = definite and tender | ||

| Extraintestinal complications | Arthritis or arthralgia; iritis or uveitis; erythema nodosum; pyoderma gangrenosum; aphthous stomatitis; anal fissure, fistula, or abscess |

From Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM: A simple index of Crohn’s disease activity. Lancet 1:514, 1980.

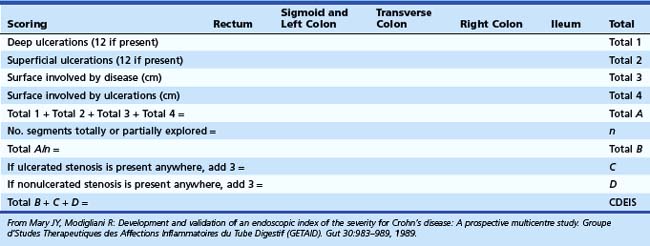

The Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS)6 is a third index and the first to use endoscopic data in assessing disease severity. This prospectively developed index was established in 1989 by the French group Groupe d’Etudes Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). The CDEIS was validated in a large multicenter trial6 and is the “gold standard” for evaluation of endoscopic, rather than clinical, activity. The bowel is divided into five segments (rectum, sigmoid and left colon, transverse colon, right colon, and ileum), and a numerical score is assigned based on objective endoscopic criteria: the presence or absence of deep or superficial ulcerations and the extent of the surface involved by the disease (Table 21.3). Scores range from 0 to 44, with higher scores indicating more severe disease. The CDEIS is reproducible, but it is time-consuming for the physician to calculate a score, which hinders its use outside of clinical trials. It also has failed to correlate with patient symptoms or other indicators of clinical activity.7

The main goal of therapy in Crohn’s disease has been to achieve remission from disease symptoms rather than to achieve endoscopic remission. Endoscopic severity previously had not been shown to correlate reliably with prognosis or to predict a clinical response to therapy.8 However, more recent studies with infliximab treatment imply that there is a longer remission and fewer disease events in patients achieving endoscopic remission.9,10 This finding may alter the role that endoscopy plays in the evaluation of the clinical course of Crohn’s disease.

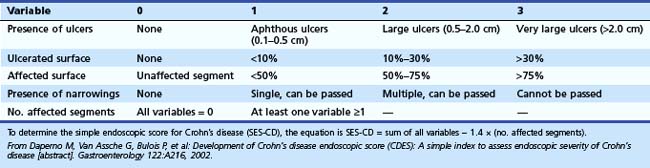

In 2002, a second severity index based on endoscopic findings was proposed: the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD).11 Because endoscopic remission has become one of the goals for monitoring treatment in clinical trials, a simpler endoscopic activity assessment than the CDEIS is needed. The bowel is divided into the same five segments as in the CDEIS, and a score of 0 to 3 is assigned based on endoscopic criteria—presence of ulcers, degree of ulcerated surface, degree of affected surface, presence of narrowings, and number of affected segments (Table 21.4). This index is easier and faster to calculate than the CDEIS. The reproducibility of the SES-CD was as good as the CDEIS, and it reliably correlated with the CDEIS, the present “gold standard.” However, similar to the CDEIS, the correlation of SES-CD results with clinically active disease was weak.

Ulcerative Colitis

The first qualitative grading system for ulcerative colitis was developed by Truelove and Witts12 in 1955. This classification system divides patients into mild, moderate, or severe disease categories based on five criteria: temperature, heart rate, hemoglobin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and diarrheal symptoms (Table 21.5). When this index was initially described, only definitions for patients with mild and severe disease were provided. This index is simple, quick, and easily applied and can identify rapidly the sickest patients with ulcerative colitis. Powell-Tuck and coworkers13 developed a scoring system to be used in their clinical trial that incorporated clinical data and endoscopic criteria. This scoring system includes a wider range of symptoms than the Truelove and Witts scoring system and includes examination for abdominal tenderness and a sigmoidoscopic scoring system. Assessment of the macroscopic sigmoidoscopic appearance is subjective, and studies have found poor correlation between the colonoscopic findings and the Powell-Tuck Activity Score.14 This finding suggests that sigmoidoscopy is not the most accurate method of assessing disease activity once the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis has been established.

Table 21.5 Truelove and Witts’ Classification of Severity in Ulcerative Colitis

| Mild | Diarrhea: <4 bowel movements daily, with only small amounts of blood |

| No fever | |

| No tachycardia | |

| ESR <30 mm/hr | |

| Moderate | Activity between mild and severe |

| Severe | Diarrhea: ≥6 bowel movements daily, with blood |

| Fever: Mean evening temperature >37.5° C or temperature >37.5° C on at least 2 of 4 days at any time of day | |

| Tachycardia: Mean pulse >90 beats/min | |

| Anemia: Hemoglobin <7.5 g/dL compared with normal, allowing for recent transfusions; ESR >30 mm/hr |

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

From Truelove SC, Witts LJ: Cortisone in ulcerative colitis: Final report on a therapeutic trial. BMJ 2:1041–1048, 1955.

The Simple Colitis Activity Index15 was developed to aid in the initial evaluation of exacerbations of ulcerative colitis by outpatient physicians. It was compared with the established Powell-Tuck Activity Score, and the authors found good correlation between the two indices (P < .0001). This simpler index includes six clinical criteria: bowel frequency during the day, bowel frequency during the night, urgency of defecation, blood in stool, general well-being, and extracolonic manifestations (Table 21.6). Because this index does not employ endoscopic or laboratory data, it may be used as an initial assessment in the outpatient setting and possibly by patients themselves as a guide to modifying treatment and the need to seek further medical advice.

Table 21.6 Simple Colitis Activity Index

| Symptoms | Score |

|---|---|

| Bowel frequency (day) | |

| 1–3 | 0 |

| 4–6 | 1 |

| 7–9 | 2 |

| >9 | 3 |

| Bowel frequency (night) | |

| 1–3 | 1 |

| 4–6 | 2 |

| Urgency of defecation | |

| Hurry | 1 |

| Immediately | 2 |

| Incontinence | 3 |

| Blood in stool | |

| Trace | 1 |

| Occasionally frank | 2 |

| Usually frank | 3 |

| General well-being | |

| Very well | 0 |

| Slightly below par | 1 |

| Poor | 2 |

| Very poor | 3 |

| Terrible | 4 |

| Extracolonic features | 1 per manifestation |

From Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, et al: A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 43:29–32, 1998.

The Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index (UCDAI) was designed in 1987 by Sutherland and coworkers16 to provide an objective basis for assessing drug efficacy. Four variables are measured, with each receiving a numerical value of 0 (normal) to 3 (most severe); a total value of 12 indicates the most severe disease. The four variables are stool frequency, amount of blood in stool, endoscopic appearance of colonic mucosa, and physician’s assessment of disease severity. A potential strength of this index is its incorporation of endoscopic appearance. A clinical response to therapy is defined as a reduction in the UCDAI score by 2 or more points. This index is very similar to another well-accepted index, often called the “Mayo score,” developed by investigators at the Mayo Clinic.17 None of the aforementioned indices that have been described for patients with ulcerative colitis has been validated. They have been accepted as being appropriate without proper formal validation.

Preparation of Patients for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Lower Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy)

The quality of colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy depends on the effectiveness of the bowel preparation. Bowel cleansing should leave no residual fecal material and only very little fluid. An inadequate bowel preparation has many repercussions: It impairs visualization and colonoscopic diagnosis; it may require the procedure to be rescheduled; and it prolongs insertion time, which not only adds to patient discomfort18 but also increases the cost of the procedure.19

In a study comparing GoLYTELY, NuLytely, and Fleet Phospho-soda, Ell and colleagues20 showed a statistically significant benefit to using GoLYTELY over the other two preparations in achieving effective cleansing of the entire colon before colonoscopy. There was no difference in patient satisfaction between the three preparations. In this study, the patients ate a regular breakfast on the day before the examination and thereafter had only clear fluids; they were not to eat anything on the day of the colonoscopy. The bowel cleansing regimen occurred in two stages, with divided doses the day before and on the morning of the procedure. A short interval between bowel preparation and colonoscopy has yielded better cleansing results.21 The GoLYTELY preparation in the past had been considered to be the “gold standard” for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. None of these studies were performed in patients with IBD, and Fleet Phospho-soda enemas have been implicated in the development of an acute colitis.

For flexible sigmoidoscopy, patient studies have not shown a clearly superior method for bowel preparation. The addition of magnesium citrate to the regimen seems to improve the quality of the study over enemas alone.22,23 Patients may consider a completely oral regimen more easily tolerated than one that includes enemas,24 but the best preparation probably would be one that includes both oral magnesium citrate and one to two Fleet enemas.25 These have yet to be adequately assessed in blinded controlled trials for patients with IBD.

Indications for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Lower Flexible Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Endoscopy plays a key role not only in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease but also in its management. Although other radiologic modalities often are complementary to the diagnosis and treatment of Crohn’s disease, endoscopy is the only method that allows for biopsy specimens to be taken. Box 21.1 lists indications for colonoscopy in IBD. Colonoscopy is usually performed during the initial evaluation of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease to confirm the diagnosis, assess disease severity, and determine the extent of the disease. It also plays an important role in assessing the disease response to therapy and is important in performing endoscopic surveillance for dysplasia or cancer. Colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy are contraindicated in patients with known or suspected peritonitis, bowel perforation, or colonic necrosis.26 Severe coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia also are contraindications for the procedure. In addition, toxic megacolon and fulminant colitis generally are relative contraindications for the procedure secondary to their increased risk of colonic perforation.

Crohn’s Disease

Lower Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Colonoscopy is performed in the initial diagnosis of Crohn’s disease to confirm the diagnosis and assess the extent of the disease. Intubation of the terminal ileum should be attempted in all patients; there is an 80% to 97% success rate of insertion of the colonoscope into the distal ileum.27,28 Biopsy specimens of the terminal ileum should be taken because Crohn’s ileitis can appear macroscopically normal. Endoscopic involvement of the ileum is usually associated with Crohn’s disease, but patients with pancolonic involvement who have ulcerative colitis can have backwash ileitis, a patchy inflammation without ulceration that extends a few centimeters into the terminal ileum. Biopsy specimens are required to differentiate the two diagnoses.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy may be appropriate to perform when a colonoscopy was recently performed or when the inflammation is known to be limited to the left side of the colon.29 In patients with severe disease activity, colonoscopy may be contraindicated secondary to the severe degree of inflammation, whereas flexible sigmoidoscopy can be useful to confirm that a patient’s symptoms are related to Crohn’s disease and not to an infectious or other form of colitis. Flexible sigmoidoscopy can also be used to confirm a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) by excluding other inflammatory or neoplastic disorders. In IBS, there is normal colonic anatomy, but there may be nonspecific findings of increased colonic mucus, mural spasm, and increased sensitivity to painful stimuli during flexible sigmoidoscopy.30

Colonic perforation is the most common major complication of diagnostic colonoscopy, with a risk of approximately 0.25%.31,32 In patients with severe colitis, a suspected abscess, toxic megacolon, or signs or symptoms of a bowel obstruction, colonoscopy is generally not recommended because the risk of perforation is greatly increased. A very small scope (6-mm outer diameter) can be used to assess the rectum and sigmoid; this technique practically eliminates the risk of colonic perforation. The proximal extent of disease can be evaluated by computed tomography (CT) scan. The most common reason to abort a colonoscopy in patients with Crohn’s disease is related to the presence of severe inflammation with large, deep ulcerations, which carry an increased risk of perforation.

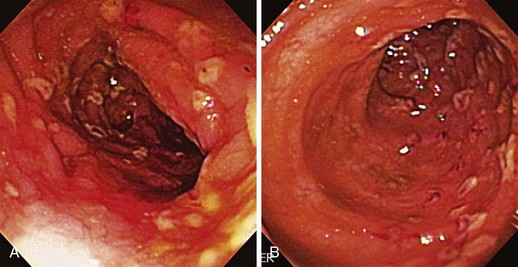

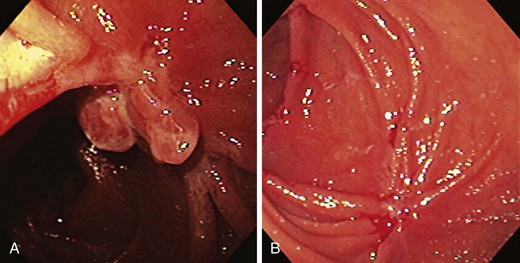

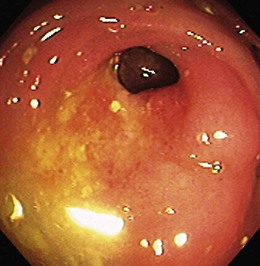

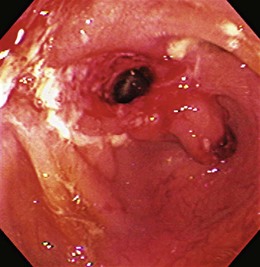

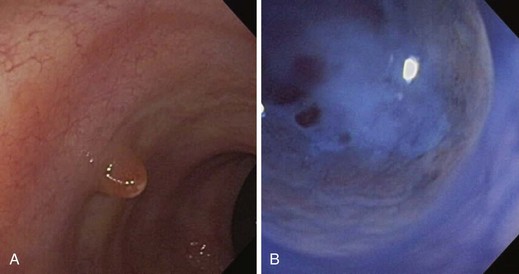

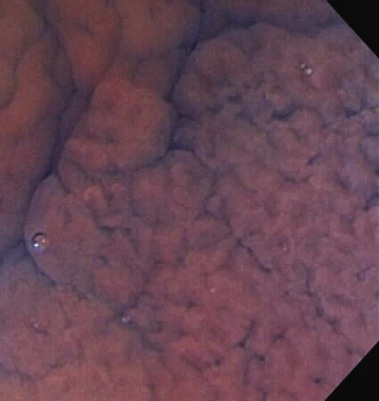

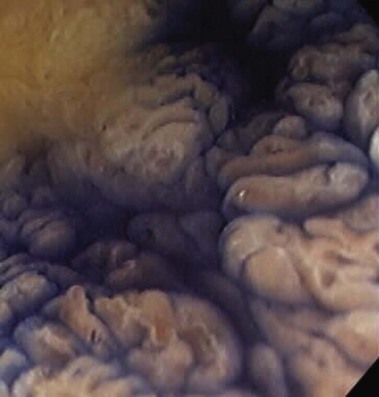

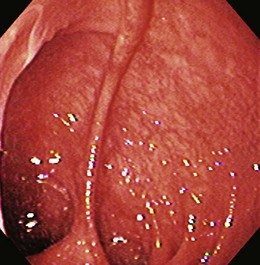

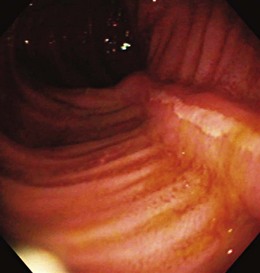

The endoscopic appearance of IBD usually is not specific enough to make the definitive diagnosis of ulcerative colitis versus Crohn’s disease; the accuracy of colonoscopy in differentiating between the two forms of inflammatory colitis is 85% to 90%.33 Some features favor one diagnosis over the other (Table 21.7). Endoscopically, Crohn’s disease tends to vary with disease duration and severity. The rectum is typically spared, with the most severe involvement occurring in the cecum and right colon; the most common patterns of disease distribution are ileocolitis in 40% to 50%, ileitis in 30% to 40%, and colitis in 15% to 25%. Classically, the disease is discontinuous, forming skip areas—areas of disease that are separated by normal mucosa. In early Crohn’s disease, small punched-out aphthous ulcers are typically seen on the background of normal mucosa (Fig. 21.1). Aphthous ulcers are a result of submucosal lymphoid follicle expansion and penetration through the mucosa. As the disease progresses, these superficial ulcerations enlarge and coalesce to become long and linear and may take on the appearance of a star (“stellate ulcers”) (Fig. 21.2). These ulcerations can deepen throughout the bowel wall to lead to abscess and fistula formation. With increasing chronicity, submucosal edema and injury results in a cobblestoning appearance, which practically is pathognomonic for Crohn’s disease; cobblestoning consists of uniform nodulations that are low in height with a broad base.

Table 21.7 Endoscopic Appearance of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

| Endoscopic Appearance | Crohn’s Disease | Ulcerative Colitis |

|---|---|---|

| Rectum | Spared | Involved |

| Vascular pattern | Normal | Early loss of vascular markings |

| Mucosal involvement | Skip lesions | Continuous |

| Ulcers | Within inflamed mucosa | Within normal mucosa |

| Mucosal granularity | Present | Present (“wet sandpaper”) |

| Mucosal friability | Present | Present |

| Cobblestoning | Present | Absent |

| Thick interhaustral septum | Present | Present |

| Pseudopolyps | Present | Present |

| Narrowing of lumen | Present | Present |

| Strictures | Present | Present |

| Fistula | Present | Absent |

| Ulcerations in terminal ileum | Present | Absent |

| Mucosal bridge | Present | Present |

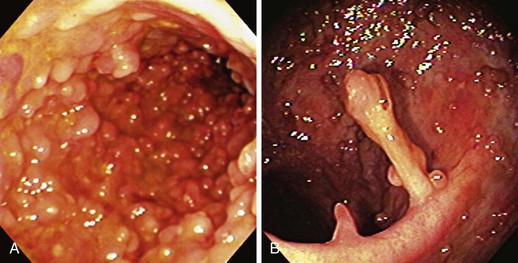

Patients with severe disease can have large linear ulcers (“bear claw” ulcers) and deep serpiginous ulcers (Figs. 21.3 and 21.4). Strictures can form in areas with transmural circumferential inflammation. Patients with moderate to severe disease activity may be endoscopically indistinguishable from patients with ulcerative colitis and many other similar diseases (Fig. 21.5). Histologically, there is transmural inflammation with predominantly lymphocytic infiltration. Granulomas are the hallmark of Crohn’s disease, although they are present in only 10% to 25% of biopsy specimens. They are more common in the early stages of the disease.34 Granulomas can be found throughout the GI tract and in macroscopically normal areas. For this reason, it is recommended that upper GI endoscopy with mucosal biopsy be performed when the differentiation between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is unclear.

Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

A hallmark of Crohn’s disease is that it can affect the entire GI tract, from the mouth to the anus. The upper GI tract was previously thought to be an uncommon site of disease, with a prevalence of less than 4%.35,36 Routine use of endoscopy has found a prevalence closer to 50% to 60%.37 Dysphagia, odynophagia, epigastric pain, and stomatitis are the most common symptoms, although most patients are asymptomatic.38–40

Endoscopic features of Crohn’s disease in the esophagus tend to be nonspecific and may include aphthous ulcers, cobblestoning, stricture formation, friability, and granularity. Huchzermeyer and coworkers41 described two different stages of esophageal involvement. The first stage is a milder and earlier form of the disease. Erythema and edema progress to aphthous ulcerations with intervening normal mucosa, resembling a cobblestoning appearance. In the second stage, esophageal strictures and stenosis occur. Histologically, it is rare to see a granuloma on a biopsy specimen of the esophagus; 75% of biopsy specimens show active chronic inflammation, and 30% show ulcerations.38

The antrum and duodenum are the most common sites of involvement of the upper GI tract (Fig. 21.6). Gastroduodenal disease is contiguous in approximately 60% of patients, with only 40% having duodenal disease solely.42 In contrast to the round and oval ulcers seen in peptic ulcer disease, the ulcerations in gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease tend to be more serpiginous and longitudinal.35 Mucosal erythema and nodularity, cobblestoning, and strictures have also been described.36,42 The descending duodenum is often the most severely affected. The pathognomonic granulomas are found in approximately 40% of biopsy specimens taken from the duodenum.42

Ulcerative Colitis

Lower Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

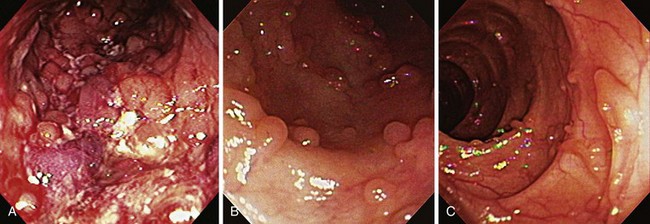

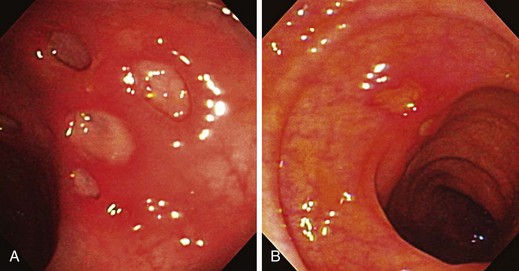

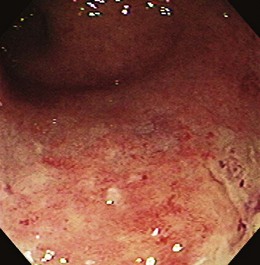

Early in the disease, there is loss of the vascular pattern and congestion. The smooth and glistening appearance of normal colonic mucosa is replaced by a more granular-appearing mucosa caused by disruption of the normal light reflection. There is blunting of the normal, finely branched mucosal vascular pattern, blunting of the intrahaustral folds caused by mucosal edema, and diffuse mucosal erythema. At later stages, the edematous mucosa acquires a sandpaperlike appearance and becomes very friable; this leads to easy mucosal bleeding, even in response to being brushed lightly by the endoscope or a cotton swab. With severe disease, mucopus, a yellow-white exudate, may be present. The colonic mucosa is disrupted, and small shallow ulcers can develop and progress to large deep ulcerations. These large ulcerations can coalesce to form areas of completely destroyed mucosa; pseudopolyps or mucosal bridges can form from the congested mucosal remnants present in the denuded areas (Figs. 21.7 and 21.8).43 Usually pseudopolyps are not clinically significant, but in patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis, biopsy of pseudopolyps is needed because they resemble adenomatous and malignant polyps (Fig. 21.9).

Toxic megacolon is a dreaded complication of colitis; although seen more often in patients with ulcerative colitis, it is found in Crohn’s disease as well. In severe colitis, damage to the neural plexus and muscularis propria can lead to neuromuscular dysfunction. Progressive colonic dilation can result leading to a toxic megacolon. In chronic ulcerative colitis, the colon appears smooth, shortened, and noncompliant (rigid) on colonoscopy. There is loss of the haustral folds caused by thickening of the muscularis mucosae and submucosal fibrosis. The colon has a characteristic pipelike appearance. The terminal ileum can also be involved in 10% to 20% of patients with ulcerative pancolitis. There is erythema, an abnormal vascular pattern, and superficial erosions in the distal 5 cm of the terminal ileum secondary to backwash ileitis. This backwash ileitis is almost always found in the setting of a dilated and incompetent ileocecal valve. Although this ileitis does not cause any clinical symptoms, retrospective data suggest that backwash ileitis is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).44

Strictures and Mass Lesions

Differentiating Malignant from Benign Strictures

The healing response to the chronic inflammation found in IBD is thought to result in intestinal strictures. It is believed that there is recruitment of fibroblasts and other structural components in healing, which promote fibrosis and luminal narrowing leading to strictures (Fig. 21.10).45 The sheer number and diversity of cell types in the intestine make it difficult to identify a solitary cell responsible for the fibrosis seen in IBD. Stricture formation is found more often in patients with Crohn’s disease than in patients with ulcerative colitis because of the transmural nature of inflammation seen in Crohn’s disease (Figs. 21.11 and 21.12). The prevalence of colonic strictures in Crohn’s disease ranges from 4% to 5% in surgical series46 to 8% to 9% in endoscopic series.47 With all strictures, it is imperative to assess for any evidence of malignancy. Although strictures are found more often in patients with Crohn’s disease, the strictures that are associated with ulcerative colitis have a higher frequency of malignancy. The rate of malignancy in patients who have strictures is 7% to 11% in Crohn’s disease48 compared with approximately 25% in ulcerative colitis.49

Efforts should be made to exclude malignancy when performing a colonoscopy (Fig. 21.13). Such efforts include visualizing the entire length of the stricture and beyond and using a narrower pediatric colonoscope, push enteroscope, or gastroscope if necessary. Biopsy specimens should be obtained from the edge and the core of the stricture. Endoscopic features suggesting malignancy within a stricture are rigidity of the edge, an eccentric lumen, nodularity within the stricture, and an abrupt shelflike margin. Even if the biopsy specimen is negative for malignancy, these highly suspicious lesions should be treated as if they were malignant because carcinoma complicating IBD can extend submucosally. Surgery should be considered in all patients with biopsy-proven malignant strictures, patients with highly suspicious lesions based on gross endoscopic assessment, and patients in whom a colonoscope is unable to pass to survey the remainder of the colon.

Role of Balloon Dilation of Strictures

Strictures that are deemed to be benign may be treated without surgical resection by using through-the-scope (TTS) balloon dilation. Strictures most amenable for endoscopic therapy are short (typically <8 cm), isolated, and located in areas of only mild inflammation. The overall success rate of TTS balloon dilation ranges from 50% to 85%.50–56 Dilation can be repeated in cases of symptomatic recurrence; both Couckuyt and colleagues50 and Sabate and coworkers57 found a 40% success rate of TTS dilation, but they also found a 40% probability of patients requiring surgery at 5-year follow-up. The complication rate of TTS balloon dilation ranges from 2.9% to 8%, with colonic perforation being the most common complication.50,54,57 No prospective randomized controlled studies have been performed to compare endoscopic treatment of strictures directly with surgical strictureplasty.

Endoscopic dilation for Crohn’s disease has been evaluated only in some small, heterogeneous studies. A more recent systematic review of the literature evaluated the efficacy of pneumatic dilation in Crohn’s disease.58 The authors reviewed 13 studies enrolling 347 patients with Crohn’s disease. Endoscopic dilation was mainly applied to postsurgical strictures and was technically successful in 86% of the cases. Long-term clinical efficacy was achieved in 58% of the patients. Mean follow-up was 33 months, corresponding to 800 patient-years of follow-up. The major complication rate was 2%; it was greater than 10% in two series. Multivariate analysis showed that a stricture length less than or equal to 4 cm was associated with a surgery-free outcome (odds ratio 4.01, 95% confidence interval 1.16 to 13.8, P < .028). The overall conclusion was that endoscopic balloon dilation is effective and safe for treatment of short strictures caused by Crohn’s disease.

Steroid injections at the time of dilation have been proposed to improve the results of balloon dilation. Ramboer and coworkers52 treated 13 patients with symptomatic strictures that precluded the passage of a standard 13-mm colonoscope. Although there was no control group, this study offered promising results because all 13 patients experienced immediate relief, and none required surgery at 47 months of follow-up. The success of the combined therapy may be secondary to a local antiinflammatory effect of the corticosteroids or a decrease in the tendency toward fibrosis after dilation or both. Intrastricture steroid injection after balloon dilation has been reported to reduce the need for repeat stricture dilation in patients with Crohn’s disease in retrospective series.

There is only one randomized pilot series performed to date. The pilot study was performed comparing local injection of triamcinolone (40 mg total dose) after endoscopic balloon dilation of Crohn’s ileocolonic anastomotic strictures versus saline placebo. The primary endpoint was time to repeat dilation or surgery. Patients were followed up for 52 weeks. In this pilot study, 13 patients were randomly assigned—7 to steroid and 6 to placebo. These groups were well matched for baseline and dilation characteristics. When evaluated by intention-to-treat analysis, one of six patients in the placebo group and five of seven patients in the steroid group needed repeat dilation (log-rank test P = .06, Cox regression P = .10, hazard ratio 6.1; 95% confidence interval 0.7 to 53.0). When analyzed by per-protocol analysis, the differences were more significant (log-rank test P = .03, Cox regression P = .07, hazard ratio 7.7; 95% confidence interval 0.9 to 67.9). The overall conclusion was that a single treatment of intrastricture triamcinolone injection did not reduce the time to repeat dilation after balloon dilation of Crohn’s ileocolonic anastomotic strictures, and there was a trend toward a worse outcome. The investigators cautioned that the use of intrastricture steroid injection after balloon dilation in clinical practice should be considered carefully until more data are available.59

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating Crohn’s Disease from Ulcerative Colitis

The accuracy of colonoscopy in differentiating Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis is approximately 85% to 90%.33 Establishing an accurate diagnosis is important because the treatment, surgical options, and prognosis often differ significantly between the two forms of colitis. It is also important to reevaluate the original diagnosis and to continue to evaluate patients with an “indeterminate colitis” because these diseases often evolve over time. Two studies looked at this phenomenon. Moum and coworkers60 studied 527 patients with ulcerative colitis, and 88% had their diagnosis confirmed at 2 years’ follow-up; 91% of the 228 patients with Crohn’s disease had their diagnosis confirmed. In 36 patients who were originally listed as “indeterminate colitis,” 33% and 17% were reclassified at 2 years as having ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Langevin and colleagues61 studied 96 patients with ulcerative proctitis; over a 29-month period, 14% developed features more consistent with Crohn’s disease.

The expression of perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) is present in most patients with ulcerative colitis, but 10% to 30% of patients with Crohn’s disease also have this antibody; these appear to be a subset of patients with Crohn’s disease who have a more ulcerative colitis–like pattern of disease: left-sided colitis, rectal bleeding, and mucus discharge.62 The anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) also is helpful in IBD. ASCA is present in 50% to 70% of patients with Crohn’s disease and in only 7% to 14% of patients with ulcerative colitis.63 These serologic tests have not been proven to play a significant role in establishing a diagnosis for an indeterminate colitis. In the rare case in which an individual has IgG and IgA ASCA positivity (the so-called double ASCA positive), there has been an excellent correlation with the presence of Crohn’s disease. Other serologic tests have been evaluated more recently. Serum markers that are available for assessing IBD include ASCA, anti-OmpC (a human antibody specific for the outer membrane porin C of Escherichia coli), ANCA, pANCA, and DNAse-sensitive pANCA (when the pANCA stain is sensitive to treatment with DNAse, it is associated with ulcerative colitis).64

Another serologic marker also has been described, anti-CBir1. The anti-CBir1 assay was developed at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Results of studies showed that 50% of patients with Crohn’s disease had concentrations of anti-CBir1 that were greater than the reference range, suggesting that anti-CBir1 had good sensitivity as a single marker for Crohn’s disease. Targan and colleagues65 showed that in a cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease who had defined serologic profiles, 46% of the patients who were nonreactive to ASCA expressed antibody to CBir1. Anti-CBir1 adds benefit to IBD serology testing. Additionally I2 antibodies have been investigated. I2 is associated with the organism Pseudomonas fluorescens. The use of serologies in the diagnosis of IBD is an area that is evolving.

Lesions such as inflammatory polyps (pseudopolyps) and mucosal bridges can occur in both forms of IBD. Mucosal bridges develop when two adjacent ulcers meet by burrowing beneath an area of inflamed mucosa, and as the area heals, reepithelialization of the ulcers and the undersurface of the mucosal strip produces a mucosal covered tube connected at both ends. There is a loss of haustral folds and linear scar formation in the healing process of both forms of colitis. The endoscopic recognition of inflammatory polyps, mucosal bridges, loss of haustral folds, or linear scarring does not offer any mechanism to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn’s disease. It is most difficult to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease when there is severe and active disease present. In the later stages of both diseases, the two forms of colitis can resemble each other so closely endoscopically that the diagnosis may be impossible until more time has passed and the patient is reexamined. The most helpful distinguishing features in Crohn’s disease are the presence of aphthous ulcers, the cobblestoning appearance, and the focal and asymmetric distribution of the colitis. In ulcerative colitis, more important differentiating endoscopic features are the small ulcers in a diffusely inflamed mucosa and the granularity and friability of the mucosa.33

Differentiating Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis from Infectious Colitis

The initial diagnosis of IBD can be challenging because many conditions share the same clinical presentation (Box 21.2). In a patient with a diarrheal illness that lasts for more than 2 weeks, IBD and infectious colitis are important considerations. A careful history including travel information, diet, and antibiotic usage and stool studies and an endoscopy with biopsy specimens often are required to make the diagnosis. It may be difficult initially to distinguish idiopathic IBD from infectious colitis because many of the clinical symptoms are similar. The endoscopic appearance of the colonic mucosa and the histologic changes in inflammatory bowel disease and infectious colitis may also be practically identical. Determining the accurate diagnosis depends on an experienced endoscopist, a reliable pathologist, and subsequent visits with the patient to observe the disease progression.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy and rectal biopsy are often adequate to distinguish between inflammatory and infectious colitis; a complete colonoscopy usually is not required.66 However, if a diagnosis cannot be made based on flexible sigmoidoscopy alone, both proximal and distal biopsy specimens of the right colon can be useful. In a patient with unexplained diarrhea of at least 4 to 6 weeks’ duration who has severe symptoms, nocturnal or frequent watery stools, weight loss, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or who is immunocompromised, it is reasonable to perform a colonoscopy with multiple biopsies.67

Approximately 30% of patients with mucoid bloody diarrhea and suspected IBD have an infectious etiology for the diarrhea.68 Many patients who present with IBD also are superinfected.69 In one study, 36% of patients with refractory ulcerative colitis had CMV found on a rectal biopsy specimen.70 Endoscopic features seen more commonly in infectious colitis include free pus, intense reddening of the surface mucosa, and yellowish exudates that partially or completely cover the mucosal surface. Patchy inflammation within the same colonic segment that consists of multiple small areas of inflammation with intervening normal-appearing mucosa is a characteristic endoscopic feature of infectious colitis.68 A brief description follows of some of the most common causes of infectious colitis and their distinctive endoscopic findings.

Actinomycosis

Actinomyces israelii is an anaerobic gram-positive bacterium that is found in the mouth, lungs, and GI tract. The most common site of GI tract involvement is the ileocecal region, and it can produce a suppurative, granulomatous infection with a propensity for fistula formation and a release of “sulfur granules.”71 Symptoms include weight loss, night sweats, draining fistulas, and abdominal masses.72 The diagnosis is confirmed by culture and histopathologic evaluation.

Amebiasis

Amebic colitis (Entamoeba histolytica) is a protozoan infection that primarily affects the large bowel.73 It is most often seen in patients who recently emigrated from developing countries and who recently traveled to developing countries. Symptoms vary from none to explosive diarrhea, tenesmus, fever, and abdominal cramps. The colonoscopic appearance during the acute phase resembles ulcerative colitis, but in the chronic phase it resembles Crohn’s disease. The most common segments involved are the cecum and right colon, with the rectum and sigmoid involved less often.74 Toxic megacolon may develop in severe cases of amebiasis. Colonoscopy reveals granular, friable, and erythematous mucosa with discrete large ulcers covered by yellowish, mucopurulent exudates.75 Biopsy specimens of the margins of the ulcers provide a 60% to 90% yield of trophozoites to make the diagnosis.76

Campylobacter jejuni

Campylobacter jejuni is a bacterial pathogen that typically causes a self-limited infectious diarrhea. It is the most commonly identified bacterial pathogen in cases of diarrhea in the United States.77 It can resemble both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.78,79 Typically, C. jejuni produces mucosal erythema and friability in the early stages and diffuse exudates over the mucosa that makes the infection indistinguishable from ulcerative colitis. The rectum is usually involved, and the right colon is rarely affected; 50% of patients may present with rectal bleeding and tenesmus similar to ulcerative colitis. Less commonly, the colonoscopic appearance resembles Crohn’s disease with hyperemia, friability, edema, and scattered small ulcers. Extraintestinal manifestations, such as erythema nodosum and peripheral arthritis, may be present.80 Hepatosplenomegaly may occur from Campylobacter infections.81 Of patients, 20% may relapse or have a prolonged illness that may mimic IBD. Dark-field or phase-contrast examination of fresh stool may be diagnostic.78

Clostridium difficile or Pseudomembranous Colitis

C. difficile is a bacterial infection that typically manifests with watery diarrhea and crampy abdominal pain after a course of antibiotic therapy.82 The characteristic colonoscopic finding is a pseudomembrane consisting of raised, yellow-white adherent plaques that range from 2 to 8 mm in diameter83; these pseudomembranes stud the surface of a moderately inflamed mucosa. The plaques typically occur in the rectum but occasionally occur exclusively in the proximal colon.84 The diagnosis is confirmed by fecal assay for C. difficile toxin A or B.85 When assessing for the presence of C. difficile, it is important to assess for the presence of both toxin A and toxin B.

Cytomegalovirus

CMV is an opportunistic viral infection that affects immunocompromised patients, most commonly patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) whose CD4 count is less than 100. Patients can be asymptomatic or may complain of abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. The presence of discrete, punched-out, shallow ulcerations is a hallmark for this disease (Fig. 21.14). This appearance can be difficult to distinguish from Crohn’s disease because there may be normal-appearing mucosa adjacent to these ulcerations; in contrast to Crohn’s disease, CMV ulcers are usually single and vary in size from 2 to 6 mm. Isolated right-sided disease is common. The diagnosis is made with a biopsy of the ulcer edges and finding CMV inclusion bodies on hematoxylin and eosin staining.86 Multiple biopsy specimens may be required because of the low density of infected cells.87

Escherichia coli O157:H7

E. coli O157:H7 is a bacterial infection that produces a hemorrhagic colitis and can lead to hemolytic uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. It is associated with contaminated undercooked beef products. Endoscopically, the mucosa appears edematous, hyperemic, and friable, mimicking Crohn’s disease.88 When assessing for the presence of E. coli O157:H7, histology is not specific and is unable to establish the presence of this versus other infectious etiologies. Definitive diagnosis is established by the finding of a positive stool culture (although stool culture has a very low yield) or detection of the molecular probes Shiga toxin A or B.

Herpes Simplex

Herpes simplex proctitis, another sexually transmitted viral infection, produces anal pain, tenesmus, rectal discharge, and constipation. It rarely affects any part of the colon more proximal than the rectum. The combination of external perianal vesicles and rectal lesions with mucosa that is erythematous, friable, and ulcerated in the distal 10 cm of the rectum is highly suggestive of herpes simplex infection. These perianal vesicles can progress to deep ulcerations. Lymphadenopathy, impotence, urinary retention, and lumbosacral dysesthesia can develop.89 To diagnose this infection, viral cultures of rectal swabs or biopsy specimens are performed.90

Histoplasma capsulatum

Histoplasmosis is a mycotic infection that rarely infects the colon. When it is present, there is usually mucosal hyperemia, friability, ulcerations, lymph node hypertrophy, and pseudopolyps in the ileocecal region.91 Histoplasmosis mimics Crohn’s disease in its predominantly right-sided distribution and its noncontiguous nature.92 The diagnosis should be considered in immunocompromised hosts and travelers from endemic areas. The organism is identified by serology, culture, or DNA probe.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis can affect any part of the large bowel and terminal ileum.93 The rectum is often spared. A deformity of the ileocecal valve and luminal narrowing in the ileocecal area are usually present. It often can be difficult to distinguish colonic tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease on colonoscopy. Both conditions produce ulcerations bordered by edema and erythema, and the ulcers are often located in areas of otherwise normal-appearing mucosa. There may be cobblestoning as a result of submucosal involvement, thickening of the bowel wall, and inflammatory pseudopolyps. Two distinctions between Crohn’s disease and M. tuberculosis endoscopically are that in the later stages the ulcers often have a rolled edge and lack the sharp definition that is seen in Crohn’s disease, and the areas of normal mucosa are shorter in colon affected by M. tuberculosis. Mass lesions or tuberculomas can develop, and fistulization may be present between loops of bowel. Caseating granulomas can be found on biopsy specimens to diagnose M. tuberculosis.94

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, similar to other sexually transmitted diseases such as herpes simplex virus and lymphogranuloma venereum, produces a proctitis. A creamy rectal discharge or rectal bleeding, rectal friability, and erythema are usually present.95 Anal intercourse is the largest risk factor for developing this proctitis. Cultures are required to distinguish N. gonorrhoeae infection from ulcerative colitis.96

Salmonella

Salmonellosis is a bacterial diarrheal illness that usually lasts less than 2 months. It primarily involves the small bowel, spares the rectum, and affects the colon only sporadically. Early in the disease, there is edema, hyperemia, and granularity of the mucosa, which progresses to petechial hemorrhages and mucosal friability. Typhoid fever, a distinctive acute systemic febrile infection caused by Salmonella, is a result of a heat-labile enterotoxin that on invasion of the mucosa causes an influx of water and electrolytes into the lumen of the bowel.97,98 As invasion occurs, localized infections develop, and the bacteremia may produce fever, headache, delirium, maculopapular rash (“rose spots”), leukopenia, and splenomegaly.99 On endoscopy, volcanolike ulcerations with a surrounding border of erythema can be seen.100

Schistosoma mansoni

Schistosoma mansoni is a parasite that is found mostly in tropical climates and may be difficult to diagnose because it is not found on routine ova and parasite examination; the encysted schistosomes are found in resected polyps or biopsy specimens.101 Schistosomiasis produces a severely inflamed colon with multiple proximal polyps that have a whitish surface exudate. The polyps are produced by the inflammatory response to the degenerating ova. Often the rectum and sigmoid colon are completely normal, but when they are involved, this disease mimics ulcerative colitis; in these cases, there are shallow ulcerations with hyperemia, friability, and edema of the mucosa.

Shigella dysenteriae

Shigella dysenteriae is a gram-negative bacterium that causes bacillary dysentery or shigellosis. The disease can be divided into two phases.102 The first phase, occurring in the first 1 to 2 days, consists of watery diarrhea and cramping; this phase is mediated by an enterotoxin. The second phase is caused by invasion of the organism into the large intestine and produces fever, cramps, bloody diarrhea, and tenesmus. Although patchy in appearance, the endoscopic appearance often resembles ulcerative colitis because there are multiple ulcers with considerable exudate. The mucosa often appears magenta-colored because of the intense erythema. S. dysenteriae infection is diagnosed with stool culture, which is positive in only 50% of cases.

Yersinia enterocolitica

Yersinia enterocolitica is an enteroinvasive bacterium that produces abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhea; symptoms can last for months. Diffuse erythema, friability, and edema throughout the entire colon produce a similar appearance to ulcerative colitis.103 Less often, there is involvement of the ileum with aphthous ulcers adjacent to normal mucosa, which resembles Crohn’s disease.103 Extraintestinal symptoms, such as arthritis, erythema nodosum, and aphthous stomatitis, can also occur. The diagnosis can be challenging because the laboratory must inoculate the proper medium for this bacteria to grow, and it can often take several weeks to show growth of the organism.

Other Inflammatory Disorders of the Colon

Disinfectant Colitis

Colonic mucosal damage can occur from the inadequate rinsing of the cleaning solutions that are used to disinfect colonoscopes.104 Colonoscopic instillation of fluid containing residual hydrogen peroxide instantaneously causes compromise to the mucosal stroma, resulting in mucosal blanching and effervescence; these white, plaquelike lesions form a pseudolipomatosis colitis and produce the “snow white” sign.105 Glutaraldehyde solution is also used in disinfecting the colonoscope; this causes direct injury to the crypt epithelium. Disinfectant colitis is a rare complication of colonoscopy.

Ischemic Colitis

Acute ischemic colitis manifests with symptoms of severe abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and abdominal distention. Atherosclerosis is the most common risk factor, but atrial fibrillation, congestive cardiomyopathy, recent aortic surgery, and hypercoagulability have also been associated with it.106 The most common sites of ischemia are the descending colon distal to the splenic flexure, the sigmoid colon, and the rectum.107 There are varying degrees of ischemic injury; there can be complete full-thickness necrosis, transient mucosal necrosis with partial resolution and residual scarring and stricture formation, or simply transient mucosal necrosis with complete resolution of the ischemia. On endoscopy, mild ischemia produces only slightly edematous mucosa. Severe ischemia causes hemorrhagic, friable, and ulcerated mucosa and often has a characteristic plum-red to blue-black coloration. These ulcerations resemble aphthous ulcers, but the clinical history and acuity usually exclude Crohn’s disease from the differential diagnosis. A biopsy can also differentiate ischemic from inflammatory colitis; ghost cells are pathognomonic for ischemia but are rarely seen.108 Usually, there are nonspecific findings of submucosal hemorrhage, vascular congestion, and interstitial edema.

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drug Colopathy

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been associated with reactivation of quiescent ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.109 In addition to this form of colitis, NSAIDs are also associated with their own de novo nonspecific colitis. The mechanism for this colitis is unclear, but it is thought to relate to prostaglandin inhibition and increased intestinal permeability. Symptoms include hematochezia, diarrhea, ulcerations, perforations, abdominal pain, and iron deficiency anemia.110 The diagnosis is based on history in conjunction with endoscopic evidence of submucosal fibrosis and focal inflammatory lesions.

Preparation-Related Colitis

Toxic or caustic materials introduced into the rectum by enema or suppository can cause colitis. Fleet Phospho-soda enemas cause a loss of normal vascular pattern, granularity, and friability in the distal colon.111 Oral sodium phosphate has also been shown to cause mucosal abnormalities.112 Small aphthouslike ulcerations are formed, which macroscopically can resemble Crohn’s disease but pathologically are easily differentiated.

Radiation Colitis

Colonic mucosa can be damaged by radiation to the pelvis and abdomen. Radiation colitis most commonly occurs in the treatment of cervical and prostate cancers. Most commonly, the distal sigmoid and proximal rectum are involved. Acutely, a patient often experiences a self-limited illness that consists of diarrhea, tenesmus, and occasional rectal bleeding. Chronic radiation colitis produces rectal bleeding that can present 20 years after the initial radiation. The mucosa is granular and friable on colonoscopy with evidence of spontaneous bleeding and telangiectasias in the rectum and sigmoid (Fig. 21.15). Radiation colitis can resemble ulcerative colitis and idiopathic proctitis.

Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare disorder of unknown etiology whose cardinal feature is isolated erythema or ulceration of a part of the rectal wall. Rectal bleeding, mucus production, constipation, rectal discomfort, and urgency also are usually present. SRUS may be initially misdiagnosed in 26% of patients.113 Ulcerated SRUS may be mistaken for IBD, and some patients have been treated with high-dose steroids. Polypoid lesions (colitis cystica profunda, seen in association with SRUS), usually found on the anterior rectal wall, have been mistaken for neoplasms. Histologically, SRUS is unique; there is evidence of fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria with disorientation of the muscularis mucosae and extension of smooth muscle fibers into the lamina propria.

SRUS affects men and women equally, and the mean age of onset is 49 years.114 The mean reported duration of symptoms before diagnosis ranges from 3 to 5 years.114–116 The diagnosis can often be made on sigmoidoscopy. Ulceration is not universally present, with polypoid, nonulcerated lesions, and erythematous areas also seen; in one series, the prevalence of ulceration was 57%, the prevalence of polypoid lesions was 25%, and the prevalence of patches of hyperemic mucosa was 18%.115

There is no specific cure for SRUS. Topical steroids and sulfasalazine enemas are ineffective.115,117 Sucralfate enemas have been used, which lead to symptomatic and macroscopic improvement, but the histologic changes persisted.118 Biofeedback techniques such as correction of pelvic floor defecatory behavior; regulation of toilet habits; and encouragement to stop laxatives, suppositories, and enemas have been shown to be useful119,120 and should be the first-line therapy for patients with SRUS. Surgery plays only a minor role in the treatment of SRUS and should be reserved for patients with intractable symptoms and patients with evidence of rectal prolapse; there is symptomatic improvement in approximately 56% of patients, but 33% are often unchanged or worse.121

Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are associated with an increased risk for developing precancerous dysplastic epithelial changes and CRC. In the general population, CRC is the third leading cause of death in the United States in both men and women and the second leading cause of cancer death overall. CRC may be one of the most preventable forms of cancer because routine colonoscopies allow detection and removal of precancerous polyps. Knowledge of CRC risk in patients with IBD is inadequate, despite the obvious conclusion that this is one of the most frightening aspects of the diagnosis of IBD. Physicians need to educate their patients and stress the importance of screening. There is no debate that ulcerative colitis bears a high risk for the development of CRC. A meta-analysis of 116 studies by Eaden and coworkers122 showed that the prevalence of CRC in patients with ulcerative colitis is approximately 3.7%. The risk for CRC increased with duration of disease: There was a 2% incidence of cancer after 10 years, a 9% incidence after 20 years, and a 19% incidence after 30 years of disease. The development of cancer accounts for one-third of deaths related to ulcerative colitis.

In contrast, data exist that both support and refute the hypothesis that Crohn’s disease is associated with an increased risk of CRC. However, increasing data show a similar risk for CRC in Crohn’s disease as in ulcerative colitis. Gillen and coworkers123 studied patients with extensive Crohn’s disease of the colon and equally extensive ulcerative colitis and found that the relative and the absolute 20-year cumulative incidence of CRC were virtually identical in both groups. Earlier studies did not adjust for the absence of colonic disease, a history of colonic resection, or the duration or extent of disease,124–126 and this probably resulted in the apparently lower risk of CRC in Crohn’s disease. Ekbom and colleagues127 found that the relative risk of CRC in patients with Crohn’s disease regardless of disease localization was approximately 2.5, but in Crohn’s colitis the relative risk was 5.6, which is similar to the relative risk seen in ulcerative colitis.

Several factors have been suggested to be associated with a higher risk for CRC in patients with IBD (Box 21.3). Most studies have examined risk factors for patients with ulcerative colitis, but it is generally extrapolated that these are probably risk factors in patients with Crohn’s disease also. Young age at diagnosis and increasing duration of disease are risk factors, with CRC rarely being diagnosed when ulcerative colitis has been present for less than 8 years; typically, surveillance with colonoscopy does not begin until after 8 years of pancolonic disease. The age of onset has been suggested to be related to the risk of developing CRC.128,129 A family history of CRC is also a risk factor. Patients with IBD have a relative risk of 2.5 for developing CRC, and patients with IBD who have a first-degree relative with CRC have a relative risk of 3.7; the relative risk is 9.2 if the first-degree relative was diagnosed before age 50 with CRC.130 The severity of inflammation and extent of the disease are also risk factors for developing CRC in most studies. It has been reported that the incidence ratio for the risk of CRC in patients with proctitis is 1.7; for patients with disease extending beyond the rectum but no further than the hepatic flexure, the incidence ratio is 2.8; and for patients with disease beyond the hepatic flexure, the incidence ratio is 14.8.129

Patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a progressive, fibrotic, cholestatic hepatobiliary inflammatory disease, seem to be at increased risk for CRC. Soetikno and coworkers131 performed a meta-analysis of 11 studies to study this association further. They found an approximate fourfold increased risk for CRC in patients with ulcerative colitis and PSC compared with patients with ulcerative colitis alone. The explanation for this association is unknown. The detection of colitis-associated CRC during colonoscopy is difficult because the dysplasia may be present in macroscopically normal mucosa; it has been suggested that only 20% to 50% of intraepithelial neoplasias can be detected by routine colonoscopy.132 Cancers in ulcerative colitis grow in a diffusely infiltrating pattern, also hindering the macroscopic diagnosis of dysplasia.133

Dysplasia is broadly classified as flat or raised based on its appearance endoscopically. Flat dysplasias occur most often in macroscopically normal mucosa and represent 95% of the dysplasia found.134 When macroscopically detectable, there is thickened mucosa with mild discoloration and a velvety appearance with evidence of nodularity. If flat dysplasia is found in a biopsy specimen, the patient should undergo a colectomy. Raised dysplasia, or a dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM), is found in less than 5% of patients with dysplasia. DALMs can be subdivided further into adenomalike and non-adenomalike dysplasia. The latter are composed of plaques, masses, or strictured lesions and are prone to progress to colon cancer135; these patients, similar to patients with flat dysplasia, should undergo total colectomy. Adenomalike DALMs appear as discrete, sessile or pedunculated polyps. If these lesions are noted on colonoscopy, the patient should undergo polypectomy and biopsy; if the biopsy is negative for adenocarcinoma, the patient does not require a colectomy but rather only increased surveillance. Further studies with long-term follow-up are required to determine the natural history of these lesions. Surveillance programs that focus on colonoscopy with biopsies have been the main method used to detect dysplasia and early cancers in patients with IBD.

In contrast to sporadic CRC, carcinogenesis in IBD does not always follow the typical dysplasia-adenoma-cancer progression. This unpredictable and highly variable sequence of events underlies the importance of increased vigilance and surveillance for CRC in a particularly high-risk population.136 Although there are no randomized controlled trials, prospective cohort studies, or case-control studies that definitively prove a benefit for surveillance colonoscopy, anecdotal and circumstantial evidence seems to suggest one. Randomized controlled trials are not likely ever to be done because most physicians would consider it unethical to withhold surveillance colonoscopy from a patient with IBD.

Endoscopic Imaging Modalities

Although more recent studies have suggested that dysplasia in IBD may be endoscopically visible,137,138 it nevertheless can be challenging to determine macroscopically if dysplasia is present. The current standard of care is to obtain four-quadrant jumbo biopsy specimens every 10 cm between the rectum and the cecum, for a total of 40 to 50 random biopsy specimens per colonoscopy in patients with ulcerative colitis. It has been estimated that 33 biopsy specimens are required to give 90% confidence in the detection of dysplasia if it is present.139 Besides the time-consuming nature and potential increased risk of procedure-related complications with increased numbers of biopsy specimens, this random biopsy approach is most limited by its nondirected technique. As a result, more recent investigative efforts are looking into newer, adjunctive endoscopic imaging modalities to direct biopsies with the goal to enhance detection and discrimination of dysplastic and neoplastic lesions.

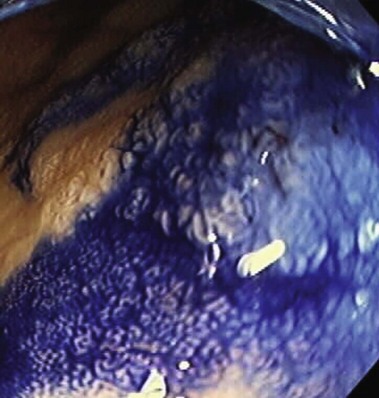

Chromoendoscopy may prove to be a more efficient way to obtain biopsy specimens of the colon (Table 21.8). In chromoendoscopy, various dyes, such as indigo carmine or methylene blue, are sprayed onto the colonic mucosa to allow for more detailed evaluation of the mucosal surface (Fig. 21.16). The rationale is to enhance the sensitivity of detection of otherwise subtle lesions, particularly in the setting of colitis. A secondary aim is to enhance the specificity via enhanced characterization of lesions (Figs. 21.17 and 21.18). Studies have shown that not only does chromoendoscopy allow for better differentiation between the neoplastic and nonneoplastic changes in the colon based on the staining pattern,140 but it also improves early diagnosis of adenomas and CRCs.141 In a randomized, controlled trial, Kiesslich and colleagues142 showed that methylene blue–aided chromoendoscopy permitted more accurate diagnosis of the extent and severity of the inflammatory activity in ulcerative colitis compared with conventional colonoscopy. More targeted biopsies were possible, and a statistically significant higher number of intraepithelial neoplasias were detected in the chromoendoscopy group—32 versus 10 in the conventional colonoscopy group (Fig. 21.19).

Table 21-8 Advantages and Disadvantages of Endoscopic Imaging Techniques

| Imaging Technology | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Chromoendoscopy | High sensitivity and specificity for detection of dysplasia | Requires specific endoscopic training for competency |

| Increase in DNA lesions with methylene blue-light treatment but unlikely to have biologic significance in vivo | ||

| No standardized procedure recommendations | ||

| Magnification endoscopy | May further improve detection of intraepithelial neoplasia, particularly in combination with chromoendoscopic techniques | Inflammation can cause significant image disturbance |

| False positivity | ||

| Not useful or practical to use zoom mode permanently when screening lower GI tract | ||

| Difficult to use at high magnification levels, particularly with peristaltic and respiratory movements | ||

| No standardized procedure recommendations | ||

| Narrow band imaging | Uniquely visualizes microvascular structure of mucosal layer | Possible difficulty in visualizing microvasculature in the setting of background mucosal inflammation |

| Similar sensitivity and specificity to chromoendoscopy for neoplastic lesions | May not be as precise as chromoendoscopy in characterization of surface pit pattern | |

| Optical coherence tomography (OCT) | Provides imaging depth beyond mucosal surface based on similar principles of ultrasound | Resolution of current OCT probes is unsatisfactory |

| May be able to predict malignant infiltration into submucosa, helping to guide decision making for mucosal resection | ||

| Fluorescence endoscopy | May allow unmasking of neoplastic lesions by fluorescent technology | Very early technology, limited studies |

| Confocal laser endomicroscopy | Allows detailed submucosal analysis and in vivo histologic examination during endoscopy | Very early technology, limited studies |

| Early studies suggest very high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for detection of presence of neoplastic lesions |

Marion and colleagues143 provided further evidence in a prospective study of patients with chronic ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis comparing methylene blue dye–spray technique with standard colonoscopic surveillance in detecting dysplasia. Their results showed that specimens obtained with targeted biopsies with dye spray revealed significantly more dysplasia (16 patients with low-grade dysplasia, 1 patient with high-grade dysplasia) than a targeted biopsy protocol (3 patients with low-grade dysplasia). Both techniques were better than conventional random biopsy specimens (four-quadrant every 10 cm), with statistical significance (Fig. 21.20).

Chromoendoscopy may prove to be extremely beneficial in the diagnosis of early CRCs in patients with IBD. Although the colonoscopies take longer to perform, with more experience and increasing sensitivity of the biopsy specimens, it still would seem to be a superior surveillance method to standard colonoscopy. The accurate prediction of histology through endoscopic visualization would be of immense value. The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Colon Cancer in IBD Study Group endorses the use of chromoendoscopy in surveillance colonoscopy for appropriately trained endoscopists.144 Consensus incorporation into general guidelines for CRC screening in IBD remains to be established, however, particularly considering the additional endoscopic training required.

Newer techniques are under investigation. Narrow band imaging (NBI) is an optical technology using filters to visualize the microvascular structure of the mucosal layer.145 NBI and chromoendoscopy showed the same sensitivity (100%) and specificity (75%) to differentiate neoplastic from nonneoplastic lesions (see Table 21.8). Comparatively, NBI achieved better visualization of the vascular network, whereas chromoendoscopy achieved more precise characterization of mucosal surface pit pattern. The value of NBI in ulcerative colitis has not yet been established, particularly in mucosa with inflammation affecting vascular structures. Less proven but promising techniques include optical coherence tomography, an optical analogue of ultrasound; fluorescence endoscopy, a technique to reveal neoplastic lesions using autofluorescence or self-induced fluorescence; and confocal laser endomicroscopy, a novel technology allowing subsurface analysis of intestinal mucosa and in vivo histologic examination. Future studies into these newer techniques and refinement of existing ones will continue to aid in further establishing appropriate guidelines and surveillance recommendations. Standardized procedure recommendations are lacking for all of the above-mentioned imaging technologies.

Pouchitis

Pouchitis is an acute inflammatory condition of a pouch or reservoir occurring after a restorative proctocolectomy or continent ileostomy. Pouchitis occurs in 30% to 46% of patients 10 years after surgery.146,147 Symptoms of pouchitis include diarrhea, urgency, abdominal pain, tenesmus, bleeding, and incontinence. If a patient previously had experienced extraintestinal symptoms of ulcerative colitis, these may often recur during an episode of pouchitis.

The cause of pouchitis is unknown. It has been related to stasis of intestinal contents and bacterial proliferation within the ileal reservoir. This hypothesis is strengthened by data that treatment with metronidazole or ciprofloxacin decreases patients’ symptoms; recurrence may arise after cessation of the antibiotics.148 Impaired use of short-chain fatty acids149 and recurrent colitis in an ileal mucosa that has undergone colonic metaplasia150 have also been suggested in the etiology of pouchitis. Women may experience pouchitis more often than men—74% versus 47%.151 For unclear reasons, smoking may be protective against pouchitis.152

Pouchitis is diagnosed by endoscopy and biopsy (Fig. 21.21). Endoscopically, the mucosa appears erythematous, friable, and nodular. There is a loss of the normal vascular pattern and contact bleeding. Aphthous ulcers may also be found within the pouch; for this reason, Crohn’s disease may resemble pouchitis on endoscopy and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pouchitis. The differential diagnosis in a patient with pouchitis is either pouchitis with Crohn’s disease–like features or Crohn’s disease in a patient with a misdiagnosis of ulcerative colitis before surgery; the latter occurs in up to 10% of patients.153 The endoscopist should always advance the scope proximal to the pouch to the ileum above the pouch, and biopsy specimens should be taken from there. Pouchitis should never spill over into the ileum above the pouch, and if inflammation is found in the ileum above the pouch, the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease should be seriously considered.

Dysplasia can occur in the rectal mucosa adjacent to the ileorectal anastomosis because a small amount (usually approximately 1 to 2 cm of rectal mucosa) of rectum remains in patients who have had ileal pouches. For this reason, patients should undergo periodic surveillance sigmoidoscopy with rectal mucosal biopsy for the evaluation of dysplasia. Risk factors that have been suggested for the development of dysplasia include a history of primary sclerosing cholangitis, prior colorectal carcinoma, or pouchitis.154

Intraoperative Endoscopy

Intraoperative endoscopy has been performed to locate areas of inflammation in the small bowel that are not well defined by radiography before surgery. The endoscope is inserted in a retrograde fashion from the distal opening of the small intestine up to the ligament of Treitz. The benefit of this procedure is questionable because, although more lesions are found intraoperatively than in radiography preoperatively, the findings do not relate to postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease.155 In one study, more than half of the lesions found on intraoperative endoscopy were not found radiographically before surgery; however, this endoscopic data modified surgery in only 2 of 20 patients.156

The endoscopic findings usually do not alter the decision of the surgeon.157 The anastomosis can be made in an area of relatively inflamed bowel or at areas of microscopic involvement because this does not seem to be a factor in the postoperative recurrence rate of Crohn’s disease.158–160 Patients treated with radical resections and patients treated with nonradical resections have the same recurrence rate; a nonradical resection is the preferred surgery for patients with Crohn’s disease.161

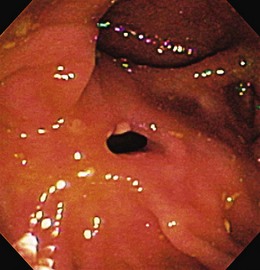

Endoscopy and Ileostomy

When the entire colon is removed in a patient with IBD, the patient can be left with a standard Brooke ileostomy, an ileoanal anastomosis with a pouch, or a continent ileostomy. An upper endoscope is often used for examination of the stoma because of its thin diameter and small radius of tip deflection. The endoscope usually can visualize the distal 10 to 20 cm of the ileostomy stoma (Fig. 21.22). Ileoscopy can be beneficial in evaluating a patient with indeterminate colitis who has undergone colectomy and is scheduled for an ileoanal anastomosis. If there is evidence of Crohn’s disease, this would argue against proceeding with the ileoanal procedure. This examination is best performed when the patient is in the supine position and can often be done without sedation.

Capsule Endoscopy

Imaging the small bowel is always a challenge for the gastroenterologist, and the methods used to visualize the small intestine were unsatisfactory until more recently. CT scan of the abdomen can show transmural thickening and extramural complications, including periintestinal fat stranding and mesenteric lymphadenopathy, but it is not sensitive enough to detect mucosal inflammation. Push endoscopy has been used more often, but it is extremely uncomfortable, can take 15 to 45 minutes, and requires sedation and analgesia, and there is a danger of perforation.162 Conventional endoscopic techniques are limited by the length of the small bowel; the endoscope can examine only 10 to 20 cm beyond the ligament of Treitz. Another approach is examination of the entire small intestine by intraoperative endoscopy; this is a more invasive method that carries the standard complication risks of general anesthesia and surgery.163

The development of wireless capsule endoscopy (video capsule endoscopy) has offered a new modality for visualizing the small bowel and more recently the upper GI tract (esophagus and stomach) and the colon. It was initially marketed in 2001. The capsule enteroscope contains a miniature video camera, a light source, batteries, and a radio transmitter. Video images are transmitted by radio waves to the sensor array that is attached to the patient. Images of the entire GI tract (for a period of up to 8 hours) can be captured and stored in a portable recorder. Capsule endoscopy has been shown to be superior to standard small bowel examination with barium for suspected small bowel disease.164 For obscure GI bleeding, evaluation with a small bowel follow-through (using barium) was less effective compared with capsule endoscopy in making a diagnosis—5% versus 31%.164 In 20 patients with suspected small bowel disease, small bowel follow-through was diagnostic in 20% of patients, whereas capsule endoscopy was diagnostic in 45% of patients, suspicious in 40%, and nondiagnostic in 15% of patients.164

In Crohn’s disease, capsule endoscopy has been shown to be a superior diagnostic tool compared with small bowel follow-through and CT. Perhaps its greatest utility lies in detection of early small bowel lesions and in diagnostic situations with negative upper and lower endoscopies, along with negative findings on traditional radiographic studies. Eliakim and coworkers165 found that capsule endoscopy established new diagnoses, confirmed existing diagnoses, established the presence of more extensive disease, and excluded the suspicion of having Crohn’s disease in 70% of patients. Small bowel follow-through accomplished this in only 37% of patients. In addition, capsule endoscopy detected all of the lesions detected by small bowel follow-through and CT and found additional lesions in 47% of cases. Capsule endoscopy was also able to rule out lesions found in other modalities in 16% of cases, making capsule endoscopy both more sensitive and more specific than barium follow-through and CT. Fireman and colleagues166 evaluated the effectiveness of wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease of the small bowel that had previously been undetected by small bowel follow-though and CT radiography and established a diagnostic yield of 71%. The capsule was able to detect mucosal erosions, ulcers, and strictures, and the degree of severity ranged from mild to severe.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

PSC is one of the most devastating complications of IBD, occurring in up to 5% of patients with ulcerative colitis and less commonly in Crohn’s disease. PSC is a cholestatic disease in which a nonsuppurative, chronic inflammation involves the biliary tree leading to progressive strictures. ERCP is the “gold standard” for diagnosis of PSC. Findings on ERCP include diffuse multifocal annular strictures of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts and a characteristic “beads on a string” appearance on cholangiography. ERCP offers the ability to obtain biopsy and brush specimens of these strictures to exclude the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.167 It also plays a key role in the nonoperative management of cholangitis associated with stricture formation, by allowing for dilation and stenting of dominant strictures.168,169 PSC can develop before any evidence of colitis is found. Up to 80% of cases of PSC are associated with IBD, most with ulcerative colitis. It is recommended that patients undergo colonoscopy with surveillance biopsy specimens to assess for the presence of subclinical colitis. If either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis is present, it is recommended that annual surveillance colonoscopic evaluation be performed in search of dysplasia.

1 Fujimura Y, Kamoi R, Iida M. Pathogenesis of aphthoid ulcers in Crohn’s disease: Correlative findings by magnifying colonoscopy, electron microscopy, and immunohistochemistry. Gut. 1996;38:724-732.

2 Hinojosa J, Abad A, Panes J, et al. Multicenter, randomized trial comparing oral, topical and oral plus topical mesalamine in the prevention of relapse in distal ulcerative colitis (DUC). Gastroenterology. 2001;120:58.

3 Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439-444.

4 Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514.

5 de Dombal FT, Softley A. IOIBD report no 1: Observer variation in calculating indices of severity and activity in Crohn’s disease. International Organisation for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut. 1987;93:727-733.

6 Mary JY, Modigliani R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn’s disease: a prospective multicentre study. Groupe d’Studes Therapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Gut. 1989;30:983-989.

7 Cellier C, Sahmoud T, Froguel E, et al. Correlations between clinical activity, endoscopic severity, and biological parameters in colonic or ileocolonic Crohn’s disease: A prospective multicentre study of 121 cases. Groupe d’Etudes Therapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Gut. 1994;35:231-235.