Chapter 16 INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterised by inflammation leading to a disturbance of gut function and, to a greater or lesser degree, systemic symptoms. Therapy is empirical. Many patients require emotional support and contact with patient support groups is often very helpful. Although these conditions are sometimes hard to differentiate, there are sufficient differences between them to indicate distinct pathological processes. Some of these differences are listed in Table 16.1.

TABLE 16.1 Characteristics of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Genetics | Identified susceptibility gene(s) | Weaker association |

| Distribution | Anywhere in the gut | Exclusively colonic |

| Perianal disease | Common | Uncommon |

| Pathology |

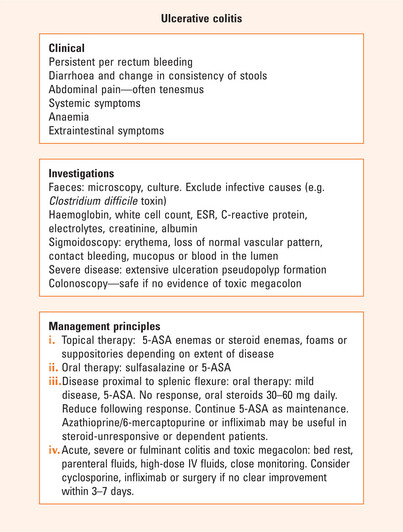

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

The extraintestinal manifestations of UC may affect the skin, joints, eyes and/or the liver (Table 16.2). These may occur before, during or after the onset of gut symptoms and may be associated with disease activity. These are generally more common in UC than Crohn’s disease.

TABLE 16.2 Extraintestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis

| Skin | Erythema nodosum |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | |

| Aphthous stomatitis | |

| Joints | Type 1 peripheral osteopathy* |

| Type 2 arthritis** | |

| Sacroileitis | |

| Eyes | Iritis |

| Uveitis | |

| Episcleritis | |

| Liver | Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

* Acute self-limiting inflammation affecting <5 joints, lasting <5 weeks and associated with symptom relapse and with other extraintestinal manifestations.

** Chronic arthritis affecting five or more joints with a median duration of symptoms of 3 years, and associated with uveitis but not erythema nodosum.

The differential diagnosis is considered in Table 16.3.

TABLE 16.3 Differential diagnosis of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

Ulcerative colitis can generally be differentiated from Crohn’s disease using endoscopic and pathological criteria (Table 16.1). UC affects the colon exclusively and almost always involves the rectum from which it extends proximally in continuity. Sigmoidoscopy will show evidence of proctitis although occasionally patients can have ‘rectal sparing’, particularly if there has been use of corticosteroid or 5-aminosalicylate enemas. Biopsies will show that the inflammation involves the more superficial layers of the mucosa, macrophages are less common and granulomata are not present. Sigmoidoscopic biopsies will help differentiate between UC and other causes of colitis, such as ischaemic colitis and radiation colitis.

Acute self-limited colitis

Some patients present with symptoms suggestive of UC, have no causative organisms grown on culture, resolve spontaneously and never have a subsequent attack. About one-half to two-thirds of patients with ‘self-limited’ colitis will develop recurrent symptoms characteristic of ulcerative colitis. The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis may be suspected after the initial presentation but is only confirmed after a subsequent attack.

Proctitis and distal colitis

In moderate disease (4–8 bloody stools daily, low-grade fever, moderate abdominal pain) oral therapy is preferred. One agent is sulfasalazine, which consists of the active moiety, 5-aminosalicylic acid linked to a carrier molecule, sulfapyridine, which prevents it from being absorbed in the proximal gut. The azo bond joining the molecules is broken down by bacteria in the terminal ileum and colon. The majority of the 5-aminosalicylic acid remains in the colon and is excreted in the faeces. The sulfapyridine is absorbed and is responsible for the majority of the side effects. Since the side effects (especially nausea, anorexia and headache) are dose-related, sulfasalazine is generally introduced at a low dose and increased gradually over a week to 3–4 g/day. If these or other side-effects occur, there are alternative ways of administering the 5-aminosalicylic acid: olsalazine comprises two molecules of 5-aminosalicylic acid linked by an azo bond; various other formulations allow for the release of 5-aminosalicylic acid in the terminal ileum and colon by coating it in resins or encapsulating it in microspheres which result in pH-dependent release of the agent.

Disease proximal to the splenic flexure

Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine are often useful in steroid-unresponsive patients or those who require high doses of steroids to remain well. The dose of azathioprine is between 2 and 2.5 mg/kg body weight and 6-mercaptopurine 1–1.5 mg/kg. Adverse effects include bone marrow suppression, liver test abnormalities, pancreatitis and a clinical syndrome characterised by high fevers and/or myalgia. Blood counts should be performed weekly for the first month, then on a regular basis every 1–3 months. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) testing can be considered to identify patients with low activity of this enzyme; they are at higher risk of bone marrow suppression and liver toxicity from azathioprine. The dose should be reduced if patients are on allopurinol therapy. If no response is seen within 3–6 months, azathioprine therapy should be withdrawn. Other approaches, including methotrexate, should be reserved for patients who are refractory to standard regimens.

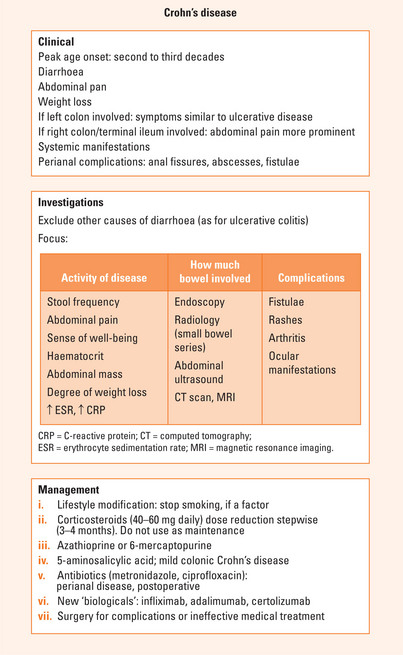

CROHN’S DISEASE

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, often debilitating disease that affects any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Patients present in many ways, but diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss are common symptoms. The condition is rarely fatal, but causes significant morbidity, particularly in young adults; the peak age of onset is in the second and third decades.

Examination may demonstrate evidence of weight loss, localised tenderness or a mass in the right iliac fossa and perianal abnormalities, including anal induration.

Assessment

Endoscopic investigations (colonoscopy and terminal ileoscopy) and radiology (small bowel series and barium enema) are the main modalities used to determine the activity and extent of disease. Unlike patients with UC, sigmoidoscopy is not always helpful in determining the presence of recurrent disease. Abdominal ultrasound and CT scan may help determine whether or not there is active disease (thickening of the bowel wall, absent peristalsis, increased vascularity) and identify complications such as abscess or fistula formation. MRI may have a role in defining the extent of perianal disease and its response to therapy. The role of videocapsule endoscopy in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease and in the monitoring of its activity is still being defined. White cell scans use radiolabelled autologous leucocytes to demonstrate sites of active inflammation and may help to define the nature of strictures seen in a small bowel series (either inflammatory or fibrotic).

Management

Drugs may be used to induce or maintain remission or both.

A Cochrane review (1998) provided the following data for the use of azathioprine and 6-MP in inducing remission in CD: the odds ratio of a response to azathioprine or 6-MP therapy compared with placebo in active Crohn’s disease was 2.36 (95% CI: 1.57 to 3.53). This corresponded to a NNT (number needed to treat) of about 5 to observe an effect of therapy in one patient. Treatment ≥17 weeks increased the odds ratio of a response to 2.51 (95% CI: 1.63 to 3.88), suggesting that there is a minimum length of time for a trial of therapy. A steroid sparing effect was seen with an odds ratio of 3.86 (95% CI: 2.14 to 6.96), corresponding to a NNT of about 3. Adverse events requiring withdrawal from a trial, principally allergy, leucopenia, pancreatitis and nausea, were increased on therapy with an odds ratio of 3.01 (95% CI: 1.30 to 6.96). The NNH to observe one adverse event in one patient treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine was 14.

Surgery is not curative, but is reserved for the treatment of complications or when medical therapy is ineffective. In historical studies, up to 70% of patients will require surgery at some stage; of these, 45%–50% will require more than one operation. It seems likely that the newer treatments and the use of effective maintenance therapy will reduce these figures in time.

Crohn’s colitis is probably associated with an increased risk of colon cancer when longstanding, and colonoscopy surveillance is recommended (Chapter 18).

SUMMARY

UC almost always involves the rectum and causes urgency and bleeding. It has a remitting and relapsing course. Investigations focus on the activity of the disease, the distribution of the disease and to decide whether complications are present. The main parameters of disease activity are the number of motions per day, the presence of blood and associated constitutional symptoms (Figure 16.1). Extraintestinal manifestations affect the skin, joints, eyes and/or the liver. Endoscopy or radiology may be used to determine the extent of the disease. The aims of therapy are to induce remission in active disease and to maintain remission/ prevent relapse. The mainstay of therapy are the corticosteroids and 5-aminosalicylates. These agents may be administered either orally or as enemas, foams or suppositories. In acute, severe or fulminant colitis, parenteral fluids, high dose intravenous steroids and close monitoring is essential. Consider cyclosporine/infliximab or surgery if there is no clear improvement within 3–7 days.

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, debilitating disease of multifactorial aetiology that affects any part of the gastrointestinal tract. There is a genetic predisposition (NOD2/CARD15) in 30%–50% of patients and other potential susceptibility genes are being assessed. Diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss are common symptoms (Figure 16.2). Left-sided CD is similar in presentation to UC. Pain is a prominent symptom in right-sided CD. Systemic symptoms are often more prominent in CD than in UC. Perianal complications are prominent in CD. Activity indices are available but are generally only used in the research situation. A patient’s well-being may be used as a subjective measure of disease activity.

Cohen RD, Woseth DM, Thisted RA, et al. A meta-analysis and overview of the literature on treatment options for left-sided ulcerative colitis and ulcerative proctitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(5):1263-1276.

Hanauer SB, Stromberg U. Oral Pentasa in the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:379-388.

Jess T, Loftus E.VJr, Harmsen WS. Survival and cause specific mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a long term outcome study in Olmsted County Minnesota. 1940-2004. Gut. 2006;55:1248-1254.

Pearson DC, May GR, Fick G, et al. Azathioprine for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2000. CD000067

Reese GE, Constantinides VA, Simillis C, et al. Diagnostic precision of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2410-2422.

Sandborn W, Sutherland L, Pearson D, et al. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2000. CD000545

Siegel CA, Hur C, Korzenik JR, et al. Risks and benefits of infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1017-1024.

Sutherland L, Roth D, Beck P, et al. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2006. CD000544