Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects approximately 1 million Americans; the incidence is equal in males and females, and the peak onset is in adolescence or early adulthood. Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease represent a chronic inflammatory process without a known specific cause. Ulcerative colitis primarily involves the colon, whereas Crohn disease involves primarily the small intestine. The distinction between ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease defies classification in as many as 10% of patients. In children, the presentation may be nonspecific, leading to a delay in diagnosis that ranges from months to years.1 Clinical and laboratory markers for active disease are inadequate; therefore repeated imaging is common, especially in patients with Crohn disease.2,3

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation

Chronic ulcerative colitis is an idiopathic inflammatory disease of the colon that typically affects older children and young adults; an infantile form has been described that is devastating and often fatal (e-Fig.107-1). The disease is characterized by mucosal inflammation, edema, and ulceration, and it is accompanied by submucosal edema in the early stages and fibrosis in the later stages. Transmural disease is uncommon. The disease may be localized in the distal colon, or it may spread to involve the entire colon and the terminal ileum. Skip areas are not characteristic, and their presence should raise the diagnosis of Crohn disease.

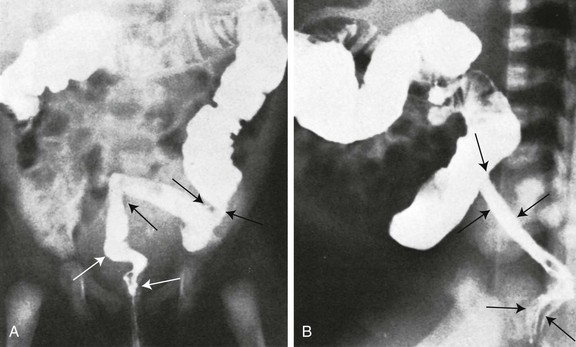

e-Figure 107-1 Infantile ulcerative colitis in a 3-week-old girl with rectal bleeding.

Frontal (A) and lateral (B) projections during barium enema show tubular narrowing of the rectum and sigmoid colon (arrows) with an abrupt transition zone. The findings were suggestive of aganglionosis, but biopsy revealed ulcerative colitis.

Crohn Disease

Crohn disease that affects the small bowel is discussed in Chapter 105. The disease can affect the colon and the small intestine. Two features that favor the diagnosis of Crohn disease over ulcerative colitis are the frequent sparing of the rectum, and the presence of skip areas in Crohn disease. Colonoscopy is often the initial examination in patients with suspected Crohn colitis, because it allows visualization of early changes and permits biopsy for diagnosis. Capsule endoscopy is commonly used in both adult and pediatric practice to visualize small-bowel abnormalities.4

Imaging

Abdominal radiographs are most often nonspecific; typically, they show an absence of recognizable stool from affected colonic segments, and they may show evidence of mucosal edema or “thumbprinting” (Fig. 107-2).5 Patients with toxic megacolon should not undergo contrast enemas because of the high risk of perforation.

Figure 107-2 Ulcerative colitis in a 14-year-old girl.

A, Abdominal radiograph shows “thumbprinting” of the distal transverse colon, suggesting submucosal edema. B, Double-contrast enema shows granularity and irregularity of the colonic mucosa. Small ulcerations are seen throughout the transverse colon and the descending colon. The entire colon was involved. C, Coned-down view of the splenic flexure shows multiple areas of pseudopolyps.

Double-contrast barium enema, formerly the diagnostic imaging procedure of choice, has been replaced by colonoscopy with biopsy.4,6 Ulcerative colitis always affects the rectum, with contiguous proximal involvement. Skip areas do not occur, although different parts of the colon may not be equally affected. The terminal ileum may become secondarily affected when there is proximal colonic involvement; terminal ileal involvement is known as backwash ileitis (e-Fig. 107-3). Ultimately, the colonic wall becomes stiff, shortened, and tubular—the “lead pipe” colon—secondary to fibrosis of the submucosa (e-Fig.107-4). Late-stage disease produces presacral thickening, and retroperitoneal fibrosis is a rare complication.

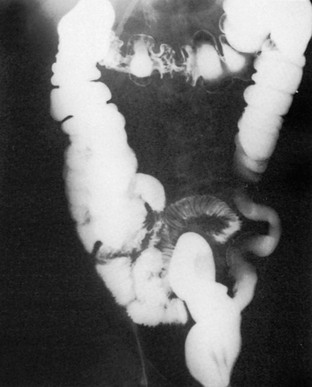

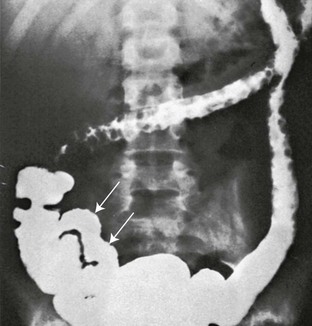

e-Figure 107-3 Ulcerative colitis with pseudopolyposis and “backwash ileitis” in a 15-year-old boy.

Multiple, round, marginal filling defects appear in the transverse and descending portions of the colon, reflecting retained islands of normal mucosa between areas of denuded mucosa. The terminal ileum (arrows) is rigid and lacks a normal mucosal pattern.

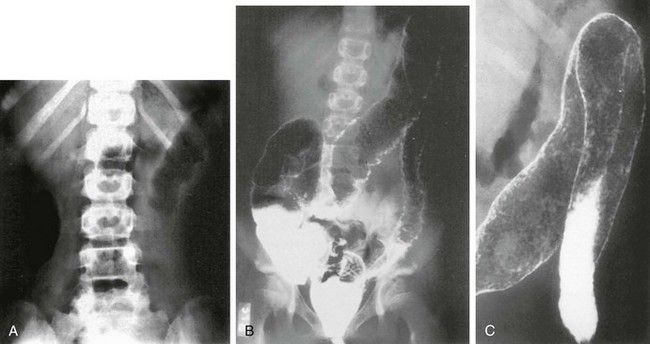

e-Figure 107-4 Ulcerative colitis in a teenage girl.

The radiographs show both acute and chronic changes of the colon resulting from ulcerative colitis. A, Abdominal radiograph shows that the transverse colon is very distended, and the left colon has a fixed, narrow “lead pipe” appearance. B, In the lower abdomen, the right colon is edematous, as seen by thumbprinting (arrows). C, The enema reveals the featureless and nondistensible left colon (“lead pipe”), resulting from fibrosis in chronic ulcerative colitis.

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be performed to investigate disease activity (abdominal pain, fever, or other symptoms), to diagnose complications, or to identify associated liver or biliary disease.7,8 When ulcerative colitis is active, cross-sectional imaging shows colonic wall enhancement with preservation of the smooth outer contour of the bowel (e-Fig.107-5). Surrounding fat stranding, mesenteric adenopathy, ascites, and, when perforation occurs, abscesses may also be evident, but extramural changes are much less common than in Crohn disease. In chronic ulcerative colitis, fatty changes may occur in the submucosa.

e-Figure 107-5 Pelvic image from abdominal-pelvic computed tomography in a 12-year-old with known ulcerative colitis.

The examination shows a smooth outer wall with marked mucosal enhancement of the rectosigmoid colon and engorgement of pelvic vessels. (Courtesy Dr. Marta Hernanz-Schulman, Nashville, TN.)

Crohn Disease

As with ulcerative colitis, double-contrast barium enemas are seldom used today for diagnosis or monitoring of disease activity. Characteristic aphthous ulcers are small and superficial, seen as an elevated edematous halo with a central umbilication caused by barium in the shallow ulcer crater. Eventually, the inflammation becomes transmural, and the characteristic “rose thorn” configuration develops from deep ulcers that extend into the thickened bowel wall. A “cobblestone” pseudopolyposis pattern, similar to that seen in the small intestine, may be apparent: areas of edematous mucosa separated by areas of denuded mucosa and deep ulcerations.9 Small-bowel follow-through (SBFT) examinations can identify complications of diseases that affect the colon, and sequelae such as enteric fistulae (Fig. 107-6). Enteroclysis is helpful in unmasking focal areas of disease activity, such as strictures (e-Fig. 107-7). Crohn disease is more likely to lead to colonic strictures than is ulcerative colitis.

Figure 107-6 Active Crohn disease with fistula formation on small-bowel follow-through.

The fistula (arrow) extends between the ileum and the medial wall of the cecum.

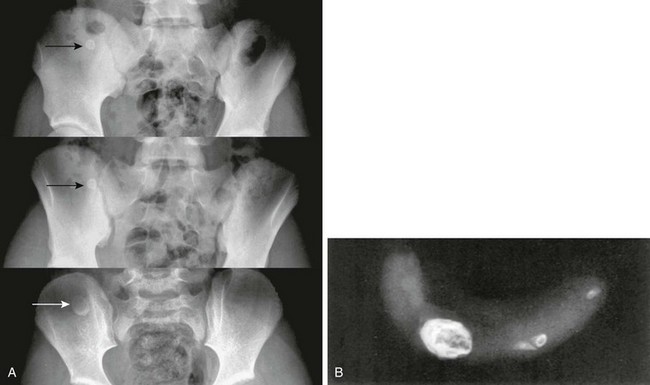

e-Figure 107-7 Crohn disease in a 12-year-old girl.

The fluoroscopic enteroclysis image shows a stricture of the terminal ileum (arrow). The stricture led to proximal obstruction and dilation and required surgical resection.

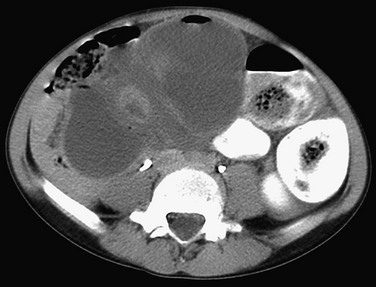

CT and MRI are very useful in evaluation of the disease activity and its complications (see Chapter 105). Extent of extramural inflammatory changes and affected loops of bowel can be identified, as can development of abscess or colonic strictures (Figs. 107-8 and 107-9).

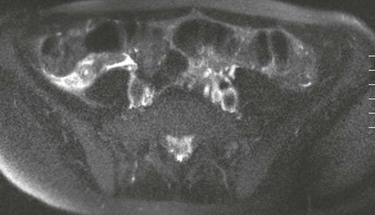

Figure 107-8 Active Crohn disease in a 19-year-old.

Computed Tomography shows the distended ileum (arrow) proximal to the thick-walled ileal loops and mesenteric stranding and vascular engorgement, resulting from active inflammation. Mural thickening and vascular engorgement of colonic segments is apparent. Positive oral contrast in the lumen interferes with evaluation of mucosal enhancement.

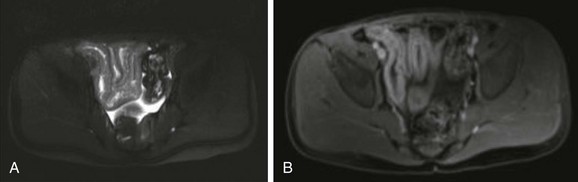

Figure 107-9 Magnetic resonance enterography of active Crohn disease in an 8-year-old boy.

A, T2-weighted axial image of the pelvis shows several thickened, contiguous loops of terminal ileum that represent active Crohn disease. B, After gadolinium administration, bright signal enhancement appears in the bowel wall relative to normal adjacent colon and rectum.

Newer imaging techniques include CT or MR enterography and CT or MR enteroclysis, which hold promise in improving the identification of disease activity and its complications. In CT enterography, the patient drinks a negative bowel contrast agent that distends the lumen more than water or traditional positive contrast and that does not mask vascular mucosal enhancement.10,11 CT enteroclysis, like small-bowel enteroclysis, is performed by using high-flow contrast introduced via nasoduodenal intubation. It is more invasive than enterography, but it provides a more controlled volume challenge to the bowel in order to define the presence of sinus tracts and fistulae and to differentiate stricture from inflammation of the bowel wall.12 CT enteroclysis has shown value in both detecting and excluding partial small-bowel obstruction and to guide specific therapies in these challenging patients.

Increasingly, pediatric centers are using MR imaging, rather than CT to avoid radiation exposure.2 Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) yields equivalent images of the small and large intestine and the intraabdominal organs.13,14 MRE is able to differentiate active inflammation from chronic inflammation in the layers of the bowel wall. Furthermore, CT and MRE are able to identify intraperitoneal complications such as fistulae and abscesses. MRE is also superior to CT for the diagnosis and management of perianal fistulae (Fig. 107-10).15–17 Some centers will image the entire abdomen and pelvis during these MR studies, because these patients may have inflammatory processes that involve the liver, pancreas, or biliary tree.

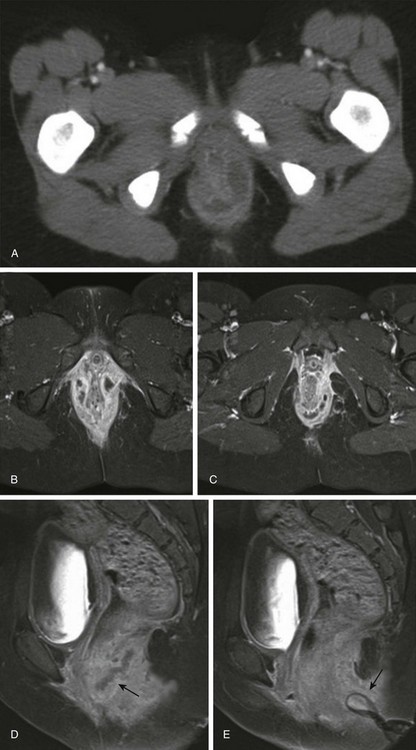

Figure 107-10 Magnetic resonance image (MRI) of perianal fistula in a girl with a new diagnosis of Crohn disease.

A, Initial axial computed tomography shows of perianal inflammation and small abscesses partially encircling the anus. B-C, Axial postcontrast fat-saturated MRI demonstrates the superior image contrast of the findings compared with CT. Exuberant inflammation (enhancement) and small abscesses nearly circumscribe the anus. D, Perianal abscesses in sagittal view (arrow). E, Superficial position of the drain (arrow) relative to the more deep position of the perianal abscess seen in image D. The patient required diverting colostomy to successfully treat her perianal disease. (Reprinted with kind permission of Springer Science+Business Media from Anupindi S, Ayyala R, Kelsen J, Mamula P, Applegate KE. Imaging of inflammatory bowel disease in children. In: Medina LS, Applegate KE, Blackmore CC, eds. Evidence-based imaging in pediatrics: optimizing imaging in pediatric patient care. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2010.)

Treatment

Initial treatment of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease is with medical therapy to suppress the inflammation. However, the majority of Crohn patients (up to 80%) and one third of ulcerative colitis patients will end up needing surgery.18,19 The most common reasons for surgery in Crohn patients are small-bowel obstructions that do not respond to medical therapy because of bowel stricture or adhesion, and bowel perforation that leads to abscess. The most common reason for surgery in pediatric ulcerative colitis patients is active disease that does not respond to medical management or that leads to complications.

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis refers to severe colonic disease that occurs in approximately 15% to 25% of patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea.20

Etiology

The toxins produced by the bacterium Clostridium difficile are the most important cause of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis.20,21 Other, less common toxins include those produced by C. perfringens and Staphylococcus aureus. The diagnosis is a clinical and laboratory one, it is more common in adults than in children, and it is rare in infants. Recently, studies have shown an association of recurrent C. difficile colitis in patients who had undergone remote appendectomy, suggesting a role of immune protection by the normal appendix.22,23

Imaging

The radiographic findings are similar to those of the other colitides.24 Enema is not necessary and should be avoided, particularly in severe cases, to avoid the risk of perforation. Ultrasound (US), MR, or CT findings of pancolitis, with or without ascites, suggest the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting.25,26

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

The hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a condition characterized by renal failure and the destruction of red blood cells. In children, it is related to foods such as undercooked meat in 90% of cases. The syndrome has a peak incidence of approximately 6.1 per 100,000 in children aged less than 5 years.27

Etiology

Most cases are caused by a Shiga-like toxin produced by Escherichia coli serotype 0157:H7, found in raw or incompletely cooked beef and unpasteurized dairy products. Additional toxins are produced by other bacterial agents and include Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter. Hemorrhagic colitis is common. Renal and central nervous system complications can markedly affect the course and prognosis of this disease.28

Clinical Presentation

This syndrome is most common during the summer months in children younger than 5 years of age. HUS usually has a gastrointestinal prodrome of diarrhea that precedes clinical evidence of acute renal failure, fever, anemia, and thrombocytopenia.28–30 A positive stool culture for the specific Shiga toxin–producing E. coli pathogen is definitive when positive. Serologic tests for antibodies to the Shiga toxin or to the lipopolysaccharide 0157 can be done, although these are not widely available.27

Imaging

US, CT, or occasionally contrast enema is generally requested before the correct diagnosis is made. The findings consist of thickening of the wall of the involved bowel segment, more typically the colon, seen as “thumbprinting” on abdominal radiographs or contrast enema, and marked bowel wall thickening on CT or US.31 The involved segments are typically in continuity without skip lesions, and pancolitis can occur. Fat stranding and free fluid are often seen near the involved segments.32 Toxic megacolon and colonic perforation have been reported, and colonic strictures can occur as a late complication.33

Radiation Colitis

Ionizing radiation treatment may cause acute inflammation during therapy. Later, chronic symptoms may be related to chronic inflammation or stricture. These changes can occur months to years after exposure and may involve the small bowel, colon, or rectum. Endarteritis, with end-vessel and microvascular circulation compromise, is the hallmark of supervening chronic ischemia.35

Etiology

Radiation injury leads to activation of mucosal cytokines and increased levels of inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-2, -6 and -8.36 Factors that affect the development of radiation colitis include patient comorbidities and, most importantly, the total radiation dose and the volume of bowel irradiated; radiation enteritis tends to develop in patients who have received on the order of 45 Gy, but it can occur with doses as low as 5 to 12 Gy.35,37

Clinical Presentation

Diarrhea, cramping, and sometimes lower intestinal bleeding are the key clinical features of the acute phase, which is usually self-limiting. Eventually, fibrosis may occur, which leads to stiffness and loss of mobility of the affected portions of the colon. Chronic radiation colitis is a progressive, precancerous disease. Additional complications include partial obstruction and fragility of the bowel, which may culminate in perforation.36 Diarrhea and abdominal pain are additional symptoms in patients with chronic radiation colitis.36

Imaging

Patients with radiation colitis do not usually undergo imaging examinations during the acute phase. Fluoroscopic imaging with either SBFT or contrast enema may delineate the chronic, fibrotic change to the affected colon (e-Fig. 107-11). CT and MR show relatively nonspecific findings of bowel wall thickening; however, the diagnostic finding is the distribution of these changes within the radiation port.35

Treatment

Treatment is related to symptom relief and includes dietary changes with reduction of fat and lactose intake in addition to medications for nausea and diarrhea. Management of patients with chronic disease can be challenging; as many as 30% of patients my require surgery for fistulae, perforation, or bowel obstruction that does not respond to nonsurgical management.37

Neutropenic Colitis

Neutropenic colitis, also known as typhlitis, is a necrotizing colitis primarily seen in children with hematopoietic malignancies, although it is also seen in children with solid tumors who undergo high-dosage chemotherapy.38 There are no definitive diagnostic criteria, although diagnosis is typically made when clinical and imaging findings are suggestive.

Etiology

The disease most often affects the cecum, hence the term typhlitis. The appendix may be involved and may produce clinical findings that mimic acute appendicitis.39 Edema and inflammation of the colon, including the distal ileum, may occur, and pneumatosis, perforation, or abscess may supervene.

Imaging

Radiographs are typically nonspecific and may show a focal ileus in the right lower quadrant. Often, a sentinel loop of dilated terminal ileum may be seen.40 Because the clinical presentation may mimic acute appendicitis, cross-sectional imaging is a critical diagnostic differentiating tool. US shows a markedly thickened cecal wall that may be either hyperechoic or hypoechoic.41 Intraluminal fluid and ascites may also be identified. CT shows marked thickening of the affected portions of the colon, which is usually more marked in the cecum; surrounding inflammatory change; and free fluid (Fig. 107-12).42 Extension of this process may involve the terminal ileum.

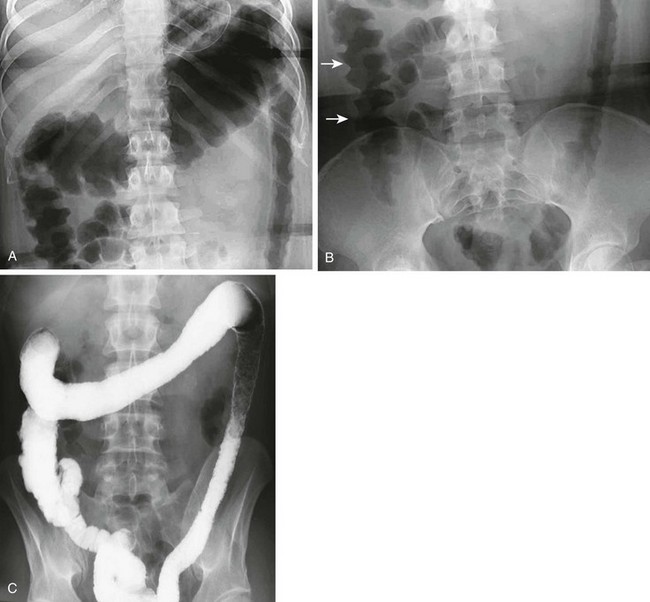

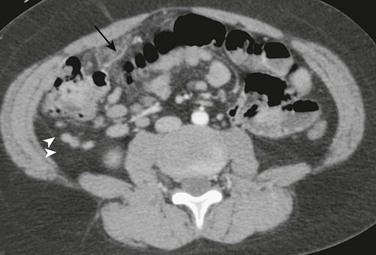

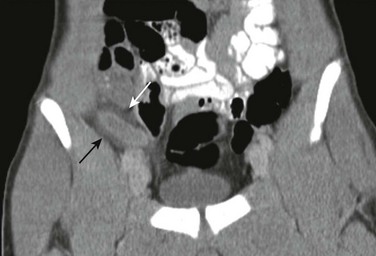

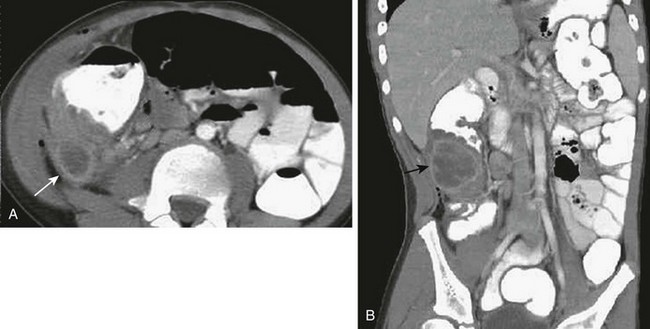

Figure 107-12 Neutropenic colitis.

Computed tomography (CT) in an 18-year-old man with acute myelogenous leukemia, fever, and neutropenia. A, Axial CT image shows the marked thickening of the cecum and a small amount of free fluid. B, Coronal CT reformat shows pancolitis, affecting the right colon to a greater extent.

Infectious Colitis

The infectious colitides are usually caused by the same agents that affect the small bowel, discussed in Chapter 105. Imaging studies are rarely needed and, when performed, usually show nonspecific colitis.31

Fibrosing Colonopathy

Fibrosing colonopathy was first described in 1994 in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) who received lipase replacement therapy.44

Etiology

With the introduction of oral, enteric-coated, high-dose pancreatic enzyme medication, clinicians increased the amount of enzyme supplements to many of these patients. Some that received particularly high doses later came to medical attention with what has been termed fibrosing colonopathy. Children were at higher risk than adults, until strict dosage guidelines were implemented. This entity is now rare because of compliance with appropriate dosage recommendations.45

Appendicitis

The vermiform appendix—a thin, tubular, intestinal diverticulum attached to the base of the cecum—is often referred to as a vestigial organ. Although conventional wisdom has long asserted that the appendix has no known function, there is evidence suggesting that it plays a role in immune function and as a reservoir for normal gut flora.22,23,47 Inflammation of the appendix remains the most common indication for surgery in both children and adults. Appendicitis in children in the United States approximates 70,000 to 90,000 cases annually with an estimated incidence of 75 to 233 per 100,000 children. The incidence increases with age and peaks in adolescence. Although rare, appendicitis does occur in young children and infants. Boys are affected more frequently than girls by a ratio of 1.4 to 1.0. Classically, appendicitis has been considered a clinical diagnosis with acceptable negative appendectomy rates between 12% and 20%.48–50 With the marked increase in use of CT and ultrasound during the past decade, these unnecessary surgeries have declined to 5% in many centers.51

Etiology

Appendicitis commonly occurs in the setting of luminal obstruction with subsequent distension of the appendix and ischemic mucosal damage, which leads to bacterial overgrowth and invasion of the wall that in turn results in transmural inflammation and ultimately in perforation. Luminal obstruction may be secondary to the presence of fecaliths, hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles, and foreign bodies that include parasites and carcinoid tumors.52 The pathophysiology of appendicitis is believed to be a dynamic process that occurs over a 24 to 36 hour period. Although infrequent, subacute appendicitis and spontaneous resolution of acute appendicitis have been described. Spontaneous resolution of luminal obstruction is the proposed pathophysiology in these cases and has been associated with cystic fibrosis and appendiceal lymphoid hyperplasia.53,54

Clinical Presentation

Appendicitis can be a challenging diagnosis in children; the clinical presentation is reported to be nonspecific in approximately one third.55 The classic clinical presentation—early periumbilical pain, followed by migration of localized pain to the right lower quadrant, with associated fever and vomiting—is reported to occur in less than 50% of pediatric patients.56 More often, the constellation of findings is nonspecific; this is particularly true in younger children who may be unable to communicate symptoms effectively, resulting in delayed diagnosis and higher perforation rates in this cohort of patients. Initial relief of pain and/or more generalized abdominal pain with fever occur after perforation, which usually results in a local abscess adjacent to the appendix; this is because the perforation is usually contained by the omentum, but generalized peritonitis can also occur. Reported perforation rates in children range from 23% to 88%.55

Imaging

Appendicitis demonstrates variable diagnostic findings on various imaging modalities (Box 107-1). Utilization of imaging, particularly CT, is increased in the emergency department for assessment of abdominal pain in children, particularly in those with suspected appendicitis.57,58 The effectiveness of imaging for suspected appendicitis in children has been debated in the medical literature, which has specifically looked at the impact of imaging on the negative appendectomy and perforation rates. Several studies suggest a stable perforation rate with preoperative imaging,59–61 whereas others demonstrate a significant decrease in perforation rate, from 35% to 15.5%, with preoperative imaging.62 However, a decrease in the negative appendectomy rate has been demonstrated in numerous studies.62–64 When the appendix is normal, the radiologist must evaluate the images for alternative diagnoses, particulary in young children. The most common alternative diagnoses, in decreasing order of prevalence, are mesenteric adenitis, ovarian cyst, pyelonephritis, infectious or inflammatory colitis, omental infarction (e-Fig. 107-13), and urinary system stones.65,66

e-Figure 107-13 Omental infarction.

Computed tomography (CT) through the lower abdomen in a young boy who underwent CT for clinically suspected appendicitis. Note typical location of edematous omentum anterior to the cecum with a prominent central vein (arrow), a classic finding in omental torsion. Portions of the normal retrocecal appendix (arrowheads) are seen, as are several incidental mesenteric nodes medial to the cecum. The patient was managed expectantly, with resolution of the symptoms. (Courtesy Dr. Marta Hernanz-Schulman, Nashville, TN.)

Radiographs

Prior to the advent of current cross-sectional imaging modalities, imaging of appendicitis relied on abdominal radiographic findings, which are often normal or nonspecific in approximately 77% of children with appendicitis.56 The presence of a radiographically visible appendicolith, considered to be the most specific radiographic sign of appendicitis, is only present in approximately 5% to 15% of patients with appendicitis.56,67 Appendicoliths are seen more frequently on CT, range from 43% to 50%, and are multiple 30% of the time (e-Fig. 107-14).68,69 Additional nonspecific radiographic findings include a paucity of bowel gas or a soft tissue mass in the right lower quadrant; ileus that may be either focal or diffuse; and less often, small-bowel obstruction.70 Mild levoconvex curvature of the spine may be present as a result of splinting in response to abdominal pain.

Ultrasound

US using a graded compression technique for evaluation of appendicitis was first described in 1986.70 Since that landmark paper, numerous studies have followed to address the efficacy of US and to evaluate additional sonographic findings.71–75 The limitations of US relate to several factors that include operator experience, larger patient body habitus, and limited field of view. Optimized technique for US evaluation of suspected appendicitis is fundamental to achieve the sensitivity. The examination is performed with a high-frequency linear transducer that ranges from 9 MHz to 15 MHz, depending on the size of the patient. A linear transducer is necessary not just to obtain the appropriate resolution but also to effect adequate graded compression. Graded compression is essential, because it displaces overlying bowel gas and also helps to decrease the distance between the transducer and the appendix. Additionally, compression helps differentiate normal bowel from an inflamed appendix. The compression is “graded,” in that it is exerted slowly, without sudden release, to optimize patient tolerance and prevent rebound tenderness. Transverse and longitudinal scans are performed over the point of maximal tenderness. If the appendix is not identified at this point, additional sonographic interrogation of the right lower quadrant, pelvis, and abdomen is necessary given the variability in location of the appendiceal tip. The most common location of the normal and abnormal appendix is in the midpelvic region over the common right iliac vessels, followed by the retrocecal region, deep pelvic region, and abdomen above the iliac crests.76

Sonographic demonstration of the normal appendix is useful in excluding the diagnosis of appendicitis, although in general US is more useful in the diagnosis than in the exclusion of appendicitis. The literature demonstrates wide operator variability with respect to reliable identification of the normal appendix, ranging from 2.4% to 86.2%.76–80 The higher percentages may reflect the advanced technology, improved resolution of US equipment, and improved operator experience. Sonographic findings associated with a normal appendix include a compressible, blind-ending tubular structure without peristalsis; diameter less than 6 mm; absence of wall thickening (less than 3 mm); and presence of a central echogenic line that represents acoustic reflection from the collapsed luminal interface (Fig. 107-15).74,80,81 The normal appendix can usually be traced to its origin at the base of the cecum (e-Fig. 107-16). Occasionally, the normal terminal ileum, often located just cephalad to the appendix, may be mistaken for a normal appendix, since it is located cephalad of the appendiceal origin. The presence of hypoechoic folds and peristalsis are helpful in differentiating the normal terminal ileum from the appendix.

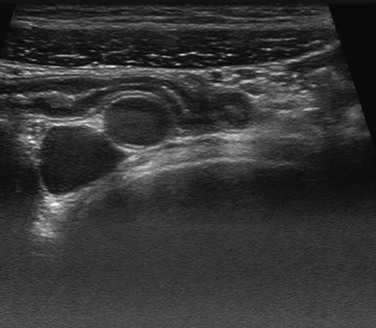

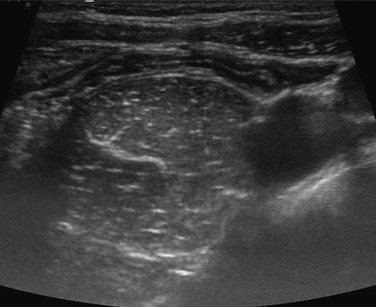

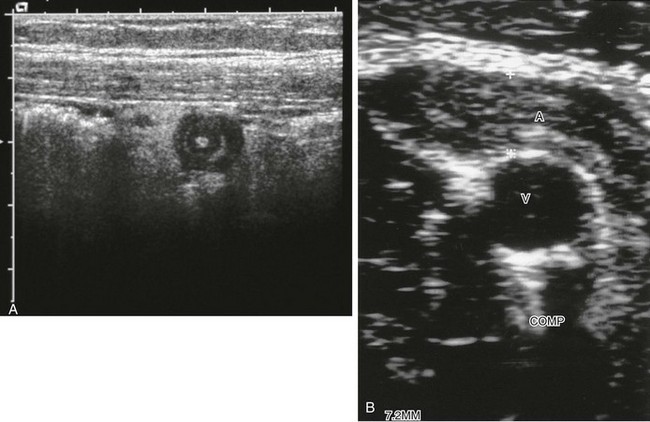

Figure 107-15 Normal appendix.

Ultrasound image of the normal appendix shows a nondilated, blind-ending tubular structure with a central echogenic line.

e-Figure 107-16 Normal appendix.

Ultrasound images of the normal appendix demonstrates the origin of the appendix at the cecum.

The single most important US sign of an inflamed appendix is a noncompressible, blind-ending tubular structure with a transverse diameter measuring greater than 6 mm. Additional sonographic signs associated with appendicitis include appendiceal wall thickness greater than 3 mm, wall hyperemia on color Doppler, periappendiceal hypoechoic halo that reflects appendiceal wall edema, periappendiceal hyperechogenicity that reflects periappendiceal edema, and the presence of an appendicolith (Fig. 107-17 and e-Fig. 107-18).75,77 The secondary sonographic findings vary, depending on the progression of the inflammatory process. Early uncomplicated appendicitis will demonstrate a targetlike appearance with hypoechogenicity centrally as a result of luminal distension with pus or fluid, increased echogencity of the inflamed submucosa, hypoechoic edematous serosa, and increased periappendiceal echogenicity (see Fig. 107-17). As the inflammatory process advances, and suppurative appendicitis ensues, the periappendiceal tissues demonstrate a heterogeneous pattern of increased echogenicity with hyperemia on color Doppler (Fig. 107-19). Increasing appendiceal dilatation, loss of the echogenic submucosal layer, and absence of vascularity with color Doppler are signs of supervening gangrenous change (Fig. 107-20). Although the abnormal appendix may not be visualized with perforated appendicitis, sonographic findings suggestive of perforation include phlegmon with poorly defined bowel loops in the right lower quadrant demonstrating overall increased echogencity, a mass of mixed echogenicity, and focal bowel wall thickening, intraperitoneal fluid, loculated fluid collections, or frank abscess.

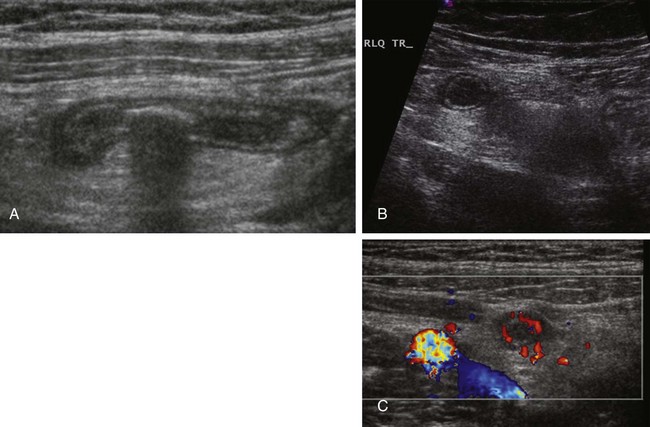

Figure 107-17 Ultrasound (US) of acute appendicitis.

A, Longitudinal US image of a dilated, noncompressible appendix containing a shadowing appendicolith. B, Transverse US image of the appendix demonstrates the characteristic target appearance with increased echogenicity of the surrounding mesenteric fat consistent with periappendiceal inflammation. C, Color Doppler interrogation shows hyperemia in the wall of the dilated appendix.

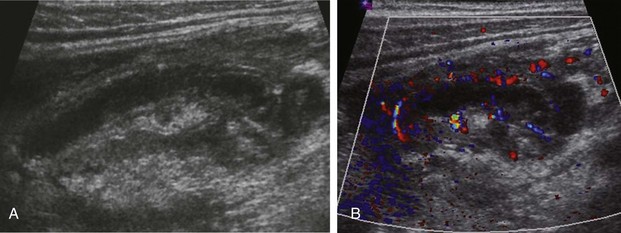

Figure 107-19 Advanced acute appendicitis.

A, Ultrasound image of an abnormal appendix with increased mixed echogenicity of the adjacent tissues and a small amount of periappendiceal fluid. B, Color Doppler interrogation demonstrates hyperemia in the wall of the appendix and in the adjacent soft tissues.

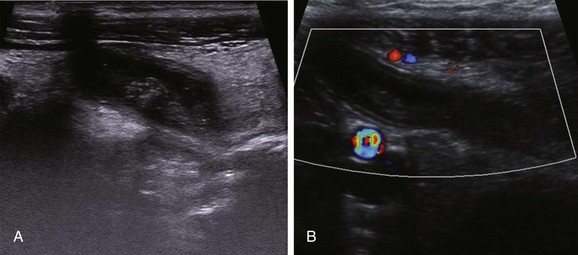

Figure 107-20 Gangrenous appendicitis.

Ultrasound images of a dilated appendix with loss of the echogenic submucosal layer and absence of vascularity with color Doppler evaluation.

e-Figure 107-18 Ultrasound of appendicitis.

A, Transverse scan of the appendix shows the characteristic target sign. In this case, the innermost portion is hyperechoic, compatible with a tiny appendicolith. B, Transverse image through the length of the appendix, which measures 7.2 mm with compression, with no appreciable change from noncompression images. A, appendix; V, vein.

Absence of visualization of an abnormal appendix in the setting of acute appendicitis may be due to a retrocecal location, obscuration by superimposed bowel gas, or limited US penetration. Additionally, appendiceal inflammatory changes may be confined to the tip of the appendix.82 If the entire appendix has not been visualized on US, and clinical symptoms suggest appendicitis or other intraperitoneal pathology, further imaging may be warranted, particularly if there are secondary signs of right lower quadrant inflammation.

Computed Tomography

CT is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis or exclusion of appendicitis in children (Table 107-1), and it is often utilized in the setting of a negative or equivocal US or perforated appendicitis. Scanning parameters should be adjusted appropriately for the size of the child to optimize dose. CT protocols vary with respect to the administration of oral, IV, and rectal contrast in addition to focal imaging versus imaging the entire abdomen and pelvis.55,81,83–86 A systematic review concluded that IV contrast alone performs as well as or better than CT with IV and positive enteral contrast for the diagnosis or exclusion of appendicitis.87

Table 107-1

| Ultrasound | Computed Tomography | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 88 (86-90) | 94 (92-97) |

| Specificity (%) | 94 (92-95) | 95 (94-97) |

Values are mean (95% confidence interval).

Doria AS, et al. US or CT for Diagnosis of Appendicitis in Children and Adults? A Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2006;241(1):83-94.

Although the average diameter of the normal appendix typically approximates 6 mm, actual size may vary on CT, from 2 to 11 mm, because the examination is not done with compression, and the appendiceal lumen may distend with gas or feces. The absence of associated CT signs of appendicitis is helpful to confirm a normal appendix. As is the case with US, the appearance of the abnormal appendix varies with the histopathologic stage and severity of the disease process. The inflamed appendix on CT is a dilated, thick-walled tubular structure with centrally decreased attenuation that demonstrates wall contrast enhancement (e-Fig. 107-21 and Fig. 107-22). An obstructing appendicolith may be present in up to 50% of cases (e-Fig. 107-23).68,69 Adjacent inflammation produces periappendiceal stranding and fluid. Additional nonspecific findings include intraperitoneal free fluid, cecal wall thickening and thickening of adjacent terminal ileum and sigmoid colon, small-bowel obstruction, and mesenteric lymphadenopathy.88

Figure 107-22 Acute appendicitis.

Coronal reformatted contrast-enhanced computed tomography image of the pelvis demonstrates a dilated appendix with wall enhancement and periappendiceal inflammation (arrows).

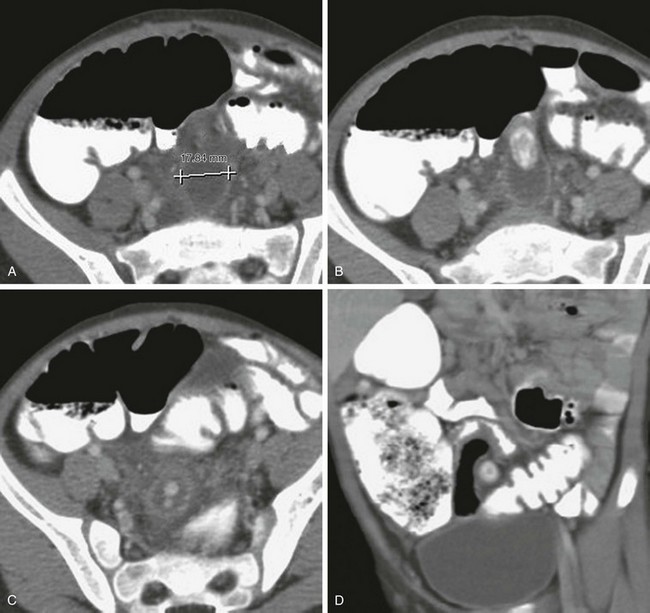

e-Figure 107-21 Acute appendicitis.

Computed tomography shows a dilated, enhancing appendix with marked periappendiceal inflammation.

e-Figure 107-23 Acute appendicitis with multiple appendicoliths.

A, Computed tomography in a 5-year-old boy with lower abdominal pain shows a markedly dilated (1.78 cm) appendix, which at first might suggest a loop of bowel. B, Large appendicolith appears proximally within the lumen. C, Sequential image show more distal, smaller appendicoliths. D, Coronal reformat shows the large appendicolith in cross section at the base of the appendix.

With perforation, the appendix may decompress or may even fail to be visualized. Perforation may result in diffuse intraperitoneal inflammation (Fig. 107-24) or, more commonly, in localized phlegmon and abscess formation (e-Figs. 107-25 and 107-26). Diffuse peritonitis is more common in infants younger than age 2 than in older children. Hepatic abscesses and mesenteric or portal pyelophlebitis can also occur. CT is extremely helpful in identifying and characterizing smaller abscesses and extruded fecaliths that may act as a potential source of recurrent infection.

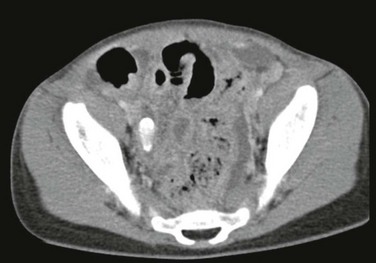

Figure 107-24 Perforated appendicitis.

Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows an appendicolith in the right lower quadrant in the remnant of the appendix. Extensive peritoneal inflammation is present with several abscesses.

e-Figure 107-25 Perforated appendix.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image of the pelvis shows an abscess in the right lower quadrant (arrows) with adjacent bowel wall thickening.

e-Figure 107-26 Perforated appendix.

A, Computed tomography (CT) image using intravenous, and enteric contrast shows a well-defined retrocecal abscess (arrow) with adjacent cecal wall thickening and mesenteric adenopathy medial to the cecum. B, Coronal CT reformat shows the full craniocaudal extent of the abscess (arrow).

Computed Tomography and Ultrasound

CT and US are reported to have a nearly equivalent specificity, 95% and 94%, respectively (see Table 107-1).89 Although CT has a greater sensitivity than US (94% and 88%, respectively although US is much more variable and operator dependent),89 concerns regarding the potential risks of ionizing radiation exposure associated with CT90 have prompted increasing use of US in the imaging evaluation of suspected appendicitis. Various imaging algorithms have been described in the literature that include the staged utilization of initial evaluation with US followed by CT for equivocal or nondiagnostic US studiess.51,83,91–93

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI has been reported to yield good results in the evaluation of suspected appendicitis, in both children and adults, using T1- and T2-weighted sequences.94–98 The sensitivity of MR was 97.6%, and the specificity was 97% in one study using a four-sequence protocol.99 The abnormal appendix demonstrates thickening of the appendiceal wall with high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, dilated lumen with high signal intensity contents on T2-weighted images, and increased signal intensity of the periappendiceal tissues (Fig. 107-27).98 Although MRI has the appealing advantage of no ionizing radiation, the current limitations that preclude routine use of MRI for imaging suspected appendicitis in children include relatively long examination time and limited availability compared with CT. The need for sedation in most young infants remains a current limitation, although faster sequence studies with a mean duration of 10 to 14 minutes have been described and performed without sedation in infants as young as 3 years.99

Treatment

Although appendectomy is the mainstay in the treatment of acute appendicitis, the literature is variable on the management of appendicitis and depends on the institution and the individual surgeon with respect to surgical procedure, timing of the surgical procedure, antibiotic therapy, and the clinical presentation of the patient.100–102 Although open appendectomy is still performed by some surgeons, laparoscopic appendectomy has become a preferred surgical approach.103 Several studies have suggested that emergent appendectomy may not be necessary, demonstrating that IV antibiotics, along with appendectomies delayed for 12 to 24 hours after presentation, do not significantly increase the rate of perforations, operative time, or length of hospital stay.104,105 Patients with perforated appendicitis undergo IV antibiotic therapy followed by interval appendectomy several weeks later. If an abscess is present, the child will typically undergo image-guided drainage.106

Miscellaneous Disorders

Etiology

A mobile cecum is a normal variant, seen in as many as 15% of individuals. Cecal volvulus is very rare in the pediatric population and results from dilatation of a mobile cecum, typically in patients with relative immobility, such as that resulting from neurologic impairment; cecal volvulus leads to severe constipation and bowel distension.107–109 Volvulus of the transverse colon is the least common form reported and is associated with abnormal fixation of the long transverse colon.110

Iatrogenic causes of cecal volvulus include the presence of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (Fig. 107-28) and the Malone antegrade continence enema procedure (e-Fig. 107-29).111 This procedure provides a catheterizable stoma for colonic enema in patients with chronic constipation, and it may provide a focal point for the bowel to twist. Sigmoid volvulus112,113 and volvulus of the transverse colon114 can also rarely occur in children. Predisposing factors are abnormal mesenteric attachments or neurologic impairment, and these lead to hypomobility and severe obstipation.108

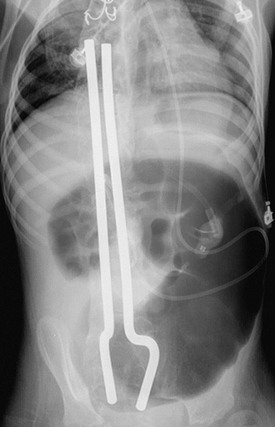

Figure 107-28 Acute cecal volvulus around ventriculoperitoneal shunt tubing.

Frontal abdominal radiograph of a teenage boy with developmental delay and chronic constipation, who presented with acute onset of vomiting and abdominal pain. The radiograph shows marked distension of a colonic loop in the left abdomen, which was found at surgery to represent an acutely twisted right colon.

e-Figure 107-29 Acute cecal volvulus around a Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE) procedure.

This 12-year-old boy came to medical attention with acute abdominal pain and vomiting without fever. He underwent rectal and intravenous contrast-enhanced CT, which showed a markedly dilated cecum. At surgery, the cecum had twisted around the MACE and was resected.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation for colonic volvulus is that of colonic obstruction with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and distension, although the findings may at times be relatively nonspecific and may be confused with gastroenteritis or some other, much more common condition.108

Imaging

Radiographs demonstrate bowel obstruction with marked dilatation of the colonic segment, which may be present in the right lower quadrant or over the midabdomen, if the volvulus involves the right colon (see Fig. 107-28). If a contrast enema is performed, the typical appearance of the site of obstructing volvulus is the “bird beak” sign. On CT imaging, enlargement of the twisted portion of the colon is apparent, as is a “whirl sign” at the site of the twist.110 The markedly enlarged colonic segment may have an enhancing thickened wall (see e-Fig. 107-29). If the bowel becomes ischemic, the wall may not enhance, and pneumatosis may be present.110

Pneumatosis Coli

Pneumatosis intestinalis, or pneumatosis coli (Fig. 107-30), is a term that refers to the radiographic, US, or CT finding of air in the wall of the intestine, and it may be due to both benign and serious clinical conditions.

Etiology

Pneumatosis is well known to occur in patients with underlying ischemic bowel disease, such as necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and in some cases of bowel obstruction. However, it is also described in a wide variety of more benign or chronic conditions, such as Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, in transplant patients, and with viral infections, particularly cytomegalovirus.116–121 Children are more likely to have pneumatosis than are adults, and depending on the etiology, the condition may generate few symptoms or may be asymptomatic. It is also described as an epiphenomenon probably caused by gas dissection in cystic fibrosis,119 and in some cases it is related to steroid therapy.

Imaging

When NEC is a clinical concern, abdominal radiography is used for the detection of associated findings that include pneumatosis, ileus, perforation, or portal venous air (see Chapter 106). Repeat radiographs are used when perforation is a concern. In other patients, pneumatosis may be an unexpected finding on radiographs. For the many associated benign conditions, and in those children who are asymptomatic, there is no evidence that serial radiographs are useful.

Sonography may detect pneumatosis of the small or large bowel and may predict outcome in patients with NEC.122,123

Dillman, JR, et al. CT enterography of pediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(1):97–105.

Doria, AS, et al. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241(1):83–94.

Fike, FB, et al. Neutropenic colitis in children. J Surg Res. 2011;170(1):73–76.

Kurbegov, AC, Sondheimer, JM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in non-neonatal pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):402–406.

Shikhare, G, Kugathasan, S. Inflammatory bowel disease in children: current trends. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(7):673–682.

Strouse, PJ. Pediatric appendicitis: an argument for US. Radiology. 2010;255(1):8–13.

References

1. Kugathasan, S, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):525–531.

2. Sauer, CG, et al. Medical radiation exposure in children with inflammatory bowel disease estimates high cumulative doses. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2326–2332.

3. Zalis, M, Singh, AK. Imaging of inflammatory bowel disease: CT and MR. Dig Dis. 2004;22(1):56–62.

4. Shikhare, G, Kugathasan, S. Inflammatory bowel disease in children: current trends. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(7):673–682.

5. Taylor, GA, et al. Plain abdominal radiographs in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1986;16(3):206–209.

6. Karjoo, M, McCarthy, B. Toxic megacolon of ulcerative colitis in infancy. Pediatrics. 1976;57(6):962–966.

7. Ajaj, WM, et al. Magnetic resonance colonography for the detection of inflammatory diseases of the large bowel: quantifying the inflammatory activity. Gut. 2005;54(2):257–263.

8. Delaney, L, et al. MR cholangiopancreatography in children: feasibility, safety, and initial experience. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(1):64–75.

9. Balachandran, S, Hayden, CK, Jr., Swischuk, LE. Filiform polyposis in a child with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1984;14(3):171–173.

10. Dillman, JR, et al. CT enterography of pediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(1):97–105.

11. Megibow, AJ, et al. Evaluation of bowel distention and bowel wall appearance by using neutral oral contrast agent for multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2006;238(1):87–95.

12. Brown, S, et al. Fluoroscopic and CT enteroclysis in children: initial experience, technical feasibility, and utility. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(5):497–510.

13. Shrot, S, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography: 4 years experience in a tertiary medical center. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13(3):172–177.

14. Sauer, CG, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance enterography with endoscopy, histopathology, and laboratory evaluation in pediatric Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(2):178–184.

15. Schwartz, DA, et al. A comparison of endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and exam under anesthesia for evaluation of Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(5):1064–1072.

16. Essary, B, et al. Pelvic MRI in children with Crohn disease and suspected perianal involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(2):201–208.

17. Sahni, VA, Ahmad, R, Burling, D. Which method is best for imaging of perianal fistula? Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(1):26–30.

18. Allmen, D, Surgical Management of Crohn’s Disease, in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mamula, P. Markowitz, JF. Baldassano, RN, New York, NY, Springer Science and Business Media, 2008:455–465.

19. Mattei, P, Rombeau, JL, Surgical Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis, in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mamula, P, Markowitz, JF. Baldassano, RN, New York, NY, Springer Science and Business Media, 2008:469–481.

20. Bartlett, JG. Antimicrobial agents implicated in Clostridium difficile toxin-associated diarrhea of colitis. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1981;149(1):6–9.

21. Faris, B, Blackmore, A, Haboubi, N. Review of medical and surgical management of Clostridium difficile infection. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14(2):97–105.

22. Im, GY, et al. The appendix may protect against Clostridium difficile recurrence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(12):1072–1077.

23. Bollinger, RR, et al. Biofilms in the normal human large bowel: fact rather than fiction. Gut. 2007;56(10):1481–1482.

24. Loughran, CF, Tappin, JA, Whitehouse, GH. The plain abdominal radiograph in pseudomembranous colitis due to Clostridium difficile. Clin Radiol. 1982;33(3):277–281.

25. Bolondi, L, et al. Sonographic appearance of pseudomembranous colitis. J Ultrasound Med. 1985;4(9):489–492.

26. Blickman, JG, et al. Pseudomembranous colitis: CT findings in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25(Suppl 1):S157–S159.

27. Mele, C, Remuzzi, G, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, in Ronco: Critical Care Nephrology. Ronco, C. Bellomo, R. Kellum, J., Philadelphia, Saunders, and Imprint of Elsevier, 2009.

28. Griffin, PM, Tauxe, RV. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and the associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1991:60–98.

29. Griffin, PM, et al. Illnesses associated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. A broad clinical spectrum. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(9):705–712.

30. Tochen, ML, Campbell, JR. Colitis in children with the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12(2):213–219.

31. Thoeni, RF, Cello, JP. CT imaging of colitis. Radiology. 2006;240(3):623–638.

32. Miller, FH, Ma, JJ, Scholz, FJ. Imaging features of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli colitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(3):619–623.

33. Sebbag, H, et al. Colonic stenosis after hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9(2):119–120.

34. Bitzan, M, Schaefer, F, Reymond, D. Treatment of typical (enteropathic) hemolytic uremic syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36(6):594–610.

35. Rha, SE, et al. CT and MR imaging findings of bowel ischemia from various primary causes. Radiographics. 2000;20(1):29–42.

36. Kountouras, J, Zavos, C. Recent advances in the management of radiation colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(48):7289–7301.

37. Theis, VS, et al. Chronic radiation enteritis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2010;22(1):70–83.

38. Abramson, SJ, Berdon, WE, Baker, DH. Childhood typhlitis: its increasing association with acute myelogenous leukemia. Report of five cases. Radiology. 1983;146(1):61–64.

39. Hobson, MJ, et al. Appendicitis in childhood hematologic malignancies: analysis and comparison with typhilitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):214–219. [discussion 219-220].

40. McNamara, MJ, et al. Typhlitis in acute childhood leukaemia: radiological features. Clin Radiol. 1986;37(1):83–86.

41. Lee, JH, et al. Gastrointestinal complications following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9(5):449–457.

42. Kirkpatrick, ID, Greenberg, HM. Gastrointestinal complications in the neutropenic patient: characterization and differentiation with abdominal CT. Radiology. 2003;226(3):668–674.

43. Fike, FB, et al. Neutropenic colitis in children. J Surg Res. 2011;170(1):73–76.

44. Smyth, RL. Fibrosing colonopathy in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74(5):464–468.

45. Lloyd-Still, JD, Beno, DW, Kimura, RM. Cystic fibrosis colonopathy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 1999;1(3):231–237.

46. Zerin, JM, et al. Colonic strictures in children with cystic fibrosis. Radiology. 1995;194(1):223–236.

47. What is the function of the human appendix? Did it once have a purpose that has since been lost? 1999 Nov 2011]. Available from http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=what-is-the-function-of-it.

48. Cooke, EA, Blackmore, CC, Imaging of appendicitis in pediatric patients. in Evidence-based imaging in pediatrics. Medina, LS. Applegate, KE, Blackmore, CC, New York, Springer, 2010:475–485.

49. Addiss, DG, et al. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910–925.

50. Puig, S, et al. Imaging of appendicitis in children and adolescents: useful or useless? A comparison of imaging techniques and a critical review of the current literature. Semin Roentgenol. 2008;43(1):22–28.

51. Hernanz-Schulman, M. CT and US in the diagnosis of appendicitis: an argument for CT. Radiology. 2010;255(1):3–7.

52. Lamps, LW. Appendicitis and infections of the appendix. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2004;21(2):86–97.

53. Migraine, S, et al. Spontaneously resolving acute appendicitis: clinical and sonographic documentation. Radiology. 1997;205(1):55–58.

54. Heller, MB, Skolnick, ML. Ultrasound documentation of spontaneously resolving appendicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11(1):51–53.

55. Sivit, CJ, Applegate, KE. Imaging of acute appendicitis in children. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2003;24(2):74–82.

56. Rothrock, SG, Pagane, J. Acute appendicitis in children: emergency department diagnosis and management. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(1):39–51.

57. Larson, DB, et al. National trends in CT use in the emergency department: 1995-2007. Radiology. 2011;258(1):164–173.

58. Broder, J, Fordham, LA, Warshauer, DM. Increasing utilization of computed tomography in the pediatric emergency department, 2000-2006. Emerg Radiol. 2007;14(4):227–232.

59. Applegate, KE, et al. Effect of cross-sectional imaging on negative appendectomy and perforation rates in children. Radiology. 2001;220(1):103–107.

60. Partrick, DA, et al. Increased CT scan utilization does not improve the diagnostic accuracy of appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(5):659–662.

61. York, D, et al. The influence of advanced radiographic imaging on the treatment of pediatric appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(12):1908–1911.

62. Pena, BM, et al. Effect of an imaging protocol on clinical outcomes among pediatric patients with appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):1088–1093.

63. Rao, PM, et al. Introduction of appendiceal CT: impact on negative appendectomy and appendiceal perforation rates. Ann Surg. 1999;229(3):344–349.

64. Smink, DS, et al. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children using a clinical practice guideline. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(3):458–463. [discussion 458-463].

65. Siegel, MJ, Carel, C, Surratt, S. Ultrasonography of acute abdominal pain in children. JAMA. 1991;266(14):1987–1989.

66. Sivit, CJ, et al. Evaluation of suspected appendicitis in children and young adults: helical CT. Radiology. 2000;216(2):430–433.

67. Brennan, GD. Pediatric appendicitis: pathophysiology and appropriate use of diagnostic imaging. CJEM. 2006;8(6):425–432.

68. Lowe, LH, et al. Appendicolith revealed on CT in children with suspected appendicitis: how specific is it in the diagnosis of appendicitis? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(4):981–984.

69. Friedland, JA, Siegel, MJ. CT appearance of acute appendicitis in childhood. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168(2):439–442.

70. Puylaert, JB. Acute appendicitis: US evaluation using graded compression. Radiology. 1986;158(2):355–360.

71. Jeffrey, RB, Jr., Laing, FC, Townsend, RR. Acute appendicitis: sonographic criteria based on 250 cases. Radiology. 1988;167(2):327–329.

72. Kao, SC, et al. Acute appendicitis in children: sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153(2):375–379.

73. Wiersma, F, et al. US examination of the appendix in children with suspected appendicitis: the additional value of secondary signs. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(2):455–461.

74. Chan, L, et al. Pathologic continuum of acute appendicitis: sonographic findings and clinical management implications. Ultrasound Q. 2011;27(2):71–79.

75. Goldin, AB, et al. Revised ultrasound criteria for appendicitis in children improve diagnostic accuracy, in Pediatr Radiol (ONLINE). Springer; 2011. [993-999].

76. Peletti, AB, Baldisserotto, M. Optimizing US examination to detect the normal and abnormal appendix in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(11):1171–1176.

77. Patriquin, HB, et al. Appendicitis in children and young adults: Doppler sonographic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166(3):629–633.

78. Kaiser, S, Frenckner, B, Jorulf, HK. Suspected appendicitis in children: US and CT–a prospective randomized study. Radiology. 2002;223(3):633–638.

79. Simonovsky, V. Sonographic detection of normal and abnormal appendix. Clin Radiol. 1999;54(8):533–539.

80. Wiersma, F, Sramek, A, Holscher, HC. US features of the normal appendix and surrounding area in children. Radiology. 2005;235(3):1018–1022.

81. Balthazar, EJ, et al. Acute appendicitis: CT and US correlation in 100 patients. Radiology. 1994;190(1):31–35.

82. Lim, HK, et al. Focal appendicitis confined to the tip: diagnosis at US. Radiology. 1996;200(3):799–801.

83. Lowe, LH, et al. Unenhanced limited CT of the abdomen in the diagnosis of appendicitis in children: comparison with sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):31–35.

84. Fefferman, NR, et al. Suspected appendicitis in children: focused CT technique for evaluation. Radiology. 2001;220(3):691–695.

85. Mullins, ME, et al. Evaluation of suspected appendicitis in children using limited helical CT and colonic contrast material. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):37–41.

86. Kaiser, S, et al. Suspected appendicitis in children: diagnosis with contrast-enhanced versus nonenhanced Helical CT. Radiology. 2004;231(2):427–433.

87. Anderson, BA, Salem, L, Flum, DR. A systematic review of whether oral contrast is necessary for the computed tomography diagnosis of appendicitis in adults. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):474–478.

88. Applegate, KE, et al. Using helical CT to diagnosis acute appendicitis in children: spectrum of findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(2):501–505.

89. Doria, AS, et al. US or CT for Diagnosis of Appendicitis in Children and Adults? A Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2006;241(1):83–94.

90. Pearce, MS, et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9840):499–505.

91. Krishnamoorthi, R, et al. Effectiveness of a staged US and CT protocol for the diagnosis of pediatric appendicitis: reducing radiation exposure in the age of ALARA. Radiology. 2011;259(1):231–239.

92. Strouse, PJ. Pediatric appendicitis: an argument for US. Radiology. 2010;255(1):8–13.

93. Toorenvliet, BR, et al. Routine ultrasound and limited computed tomography for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. World J Surg. 2010;34(10):2278–2285.

94. Cobben, L, et al. A simple MRI protocol in patients with clinically suspected appendicitis: results in 138 patients and effect on outcome of appendectomy. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(5):1175–1183.

95. Hormann, M, et al. MR imaging in children with nonperforated acute appendicitis: value of unenhanced MR imaging in sonographically selected cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(2):467–470.

96. Hormann, M, et al. MR imaging of the normal appendix in children. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(9):2313–2316.

97. Incesu, L, et al. Acute appendicitis: MR imaging and sonographic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168(3):669–674.

98. Nitta, N, et al. MR imaging of the normal appendix and acute appendicitis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21(2):156–165.

99. Moore, MM, et al. MRI for clinically suspected pediatric appendicitis: an implemented program. Pediatr Radiol. 2012.

100. Muehlstedt, SG, Pham, TQ, Schmeling, DJ. The management of pediatric appendicitis: a survey of North American Pediatric Surgeons. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(6):875–879. [discussion 875-879].

101. Newman, K, et al. Appendicitis 2000: variability in practice, outcomes, and resource utilization at thirty pediatric hospitals. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(3):372–379. [discussion 372-379].

102. Chen, C, et al. Current practice patterns in the treatment of perforated appendicitis in children. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(2):212–221.

103. Lee, SL, Yaghoubian, A, Kaji, A. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy in children: outcomes comparison based on age, sex, and perforation status. Arch Surg. 2011;146(10):1118–1121.

104. Abou-Nukta, F, et al. Effects of delaying appendectomy for acute appendicitis for 12 to 24 hours. Arch Surg. 2006;141(5):504–506. [discussion 506-507].

105. Yardeni, D, et al. Delayed versus immediate surgery in acute appendicitis: do we need to operate during the night? J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(3):464–469. [discussion 464-469].

106. Morrow, SE, Newman, KD. Current management of appendicitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16(1):34–40.

107. Kirks, DR. The radiology of enteritis due to hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1982;12(4):179–183.

108. Andersen, JF, Eklof, O, Thomasson, B. Large bowel volvulus in children. Review of a case material and the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 1981;11(3):129–138.

109. Berger, RB, et al. Volvulus of the ascending colon: an unusual complication of non-rotation of the midgut. Pediatr Radiol. 1982;12(6):298–300.

110. Peterson, CM, et al. Volvulus of the gastrointestinal tract: appearances at multimodality imaging. Radiographics. 2009;29(5):1281–1293.

111. Kokoska, ER, et al. Cecal volvulus: a report of two cases occurring after the antegrade colonic enema procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(6):916–919. [discussion 916-919].

112. Campbell, JR, Blank, E. Sigmoid volvulus in children. Pediatrics. 1974;53(5):702–705.

113. Ton, MN, et al. Recurrent sigmoid volvulus in a sixteen-year-old boy: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(9):1434–1436.

114. Reinarz, S, et al. Splenic flexure volvulus: a complication of pseudoobstruction in infancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145(6):1303–1304.

115. Mellor, MF, Drake, DG. Colonic volvulus in children: value of barium enema for diagnosis and treatment in 14 children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(5):1157–1159.

116. Dubinsky, MC, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis and colocolic intussusception complicating Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(1):96–98.

117. Kurbegov, AC, Sondheimer, JM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in non-neonatal pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):402–406.

118. Yeager, AM, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis in children after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Pediatr Radiol. 1987;17(1):18–22.

119. Hernanz-Schulman, M, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis in cystic fibrosis. Radiology. 1986;160(2):497–499.

120. Chelimsky, G, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis and diarrhea in a child following renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2003;7(3):236–239.

121. Sivit, CJ, et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis in children with AIDS. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155(1):133–134.

122. Goske, MJ, et al. The “circle sign”: a new sonographic sign of pneumatosis intestinalis–clinical, pathologic and experimental findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29(7):530–535.

123. Silva, CT, et al. Correlation of sonographic findings and outcome in necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(3):274–282.