Chapter 2 Inflammation

Inflammation

Inflammation is the dynamic process by which living tissues react to injury. They concern vascular and connective tissues particularly.

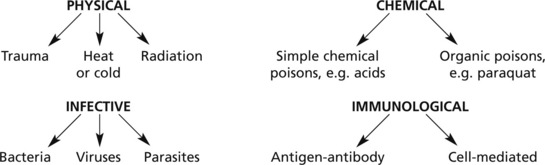

Various agents may kill or damage cells:

… and any other circumstance leading to tissue damage, e.g. vascular or hormonal disturbance.

Acute Inflammation

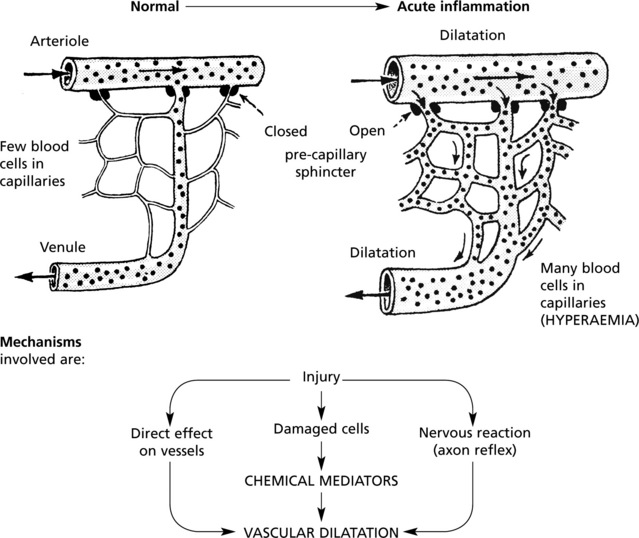

Hyperaemia

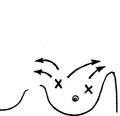

The hyperaemia in inflammation is associated with the well known microvascular changes which occur in Lewis’ triple response – a FLUSH, a FLARE and a WEAL. It occurs when a blunt instrument is drawn firmly across the skin and illustrates the vascular changes occurring in acute inflammation.

The stroke is marked momentarily by a white line due to vasoconstriction.

The flush, a dull red line, immediately follows and is due to capillary dilatation.

The flare, a bright red irregular surrounding zone, is due to arteriolar dilatation.

hyperaemia explains the classical signs of redness and heat.

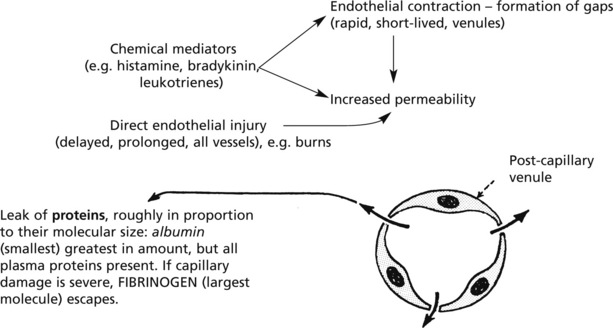

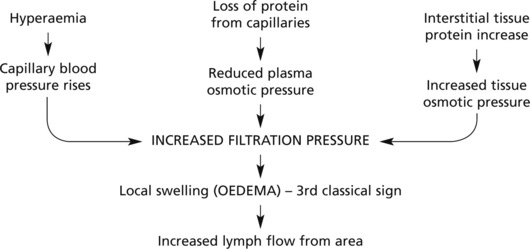

Exudation

Exudation is the increased passage of protein-rich fluid through the vessel wall into the interstitial tissue. It explains the weal in Lewis’ triple response.

| Advantageous results | Contents of fluid |

|---|---|

| Fluid increase | (a) Globulins → protective antibodies |

| ↓ | (b) Fibrin deposition → Helps to limit spread of bacteria |

| Dilution of toxins | (c) Various factors promoting subsequent healing |

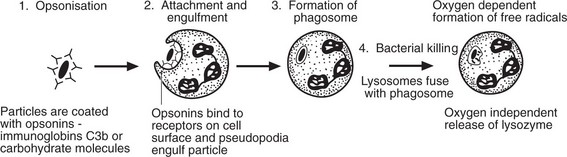

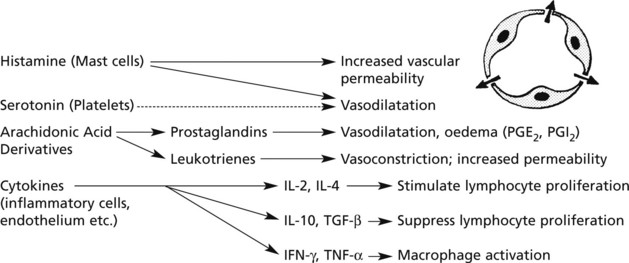

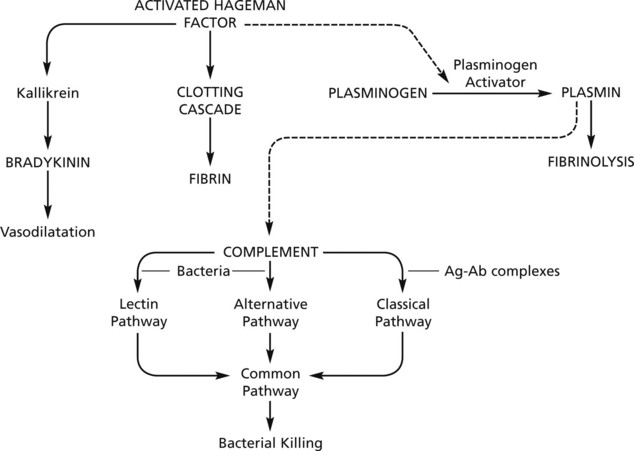

Emigration of Leucocytes

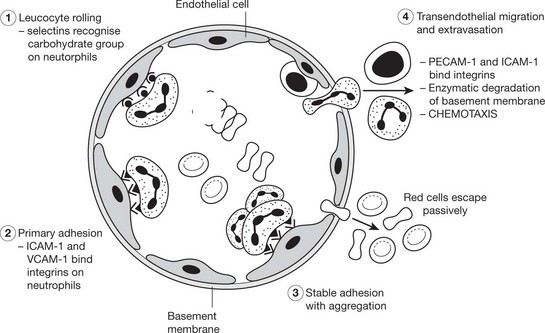

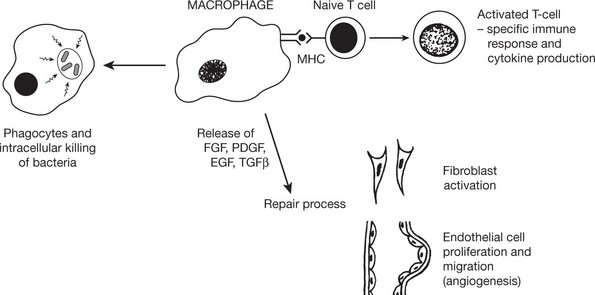

Neutrophils and mononuclears pass between the endothelial cell junctions by amoeboid movement through the venule wall into the tissue spaces. In this process both neutrophils and endothelial cells are activated and both express cell adhesion molecules, initially

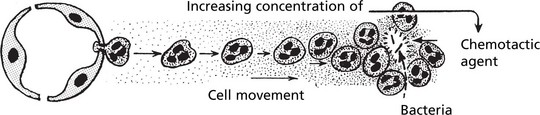

Chemotaxis

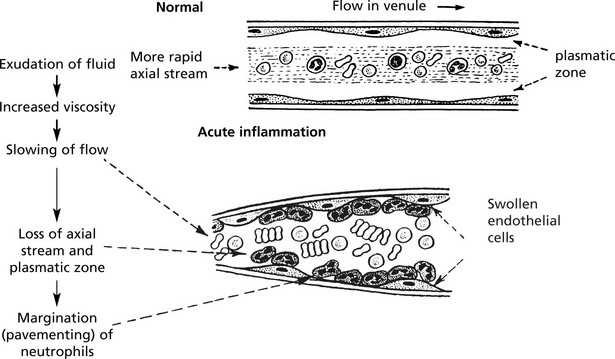

The initial margination of neutrophils and mononuclears is potentiated by slowing of blood flow and by increased ‘stickiness’ of the endothelial surface.

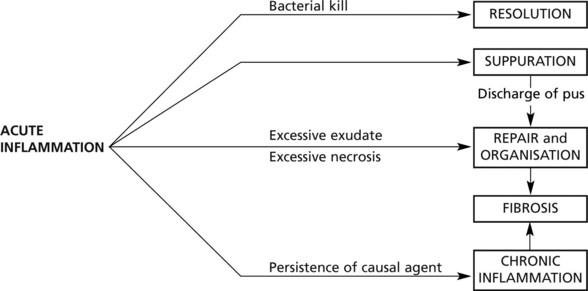

Sequels of Acute Inflammation

Resolution

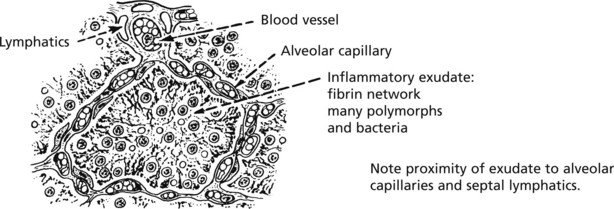

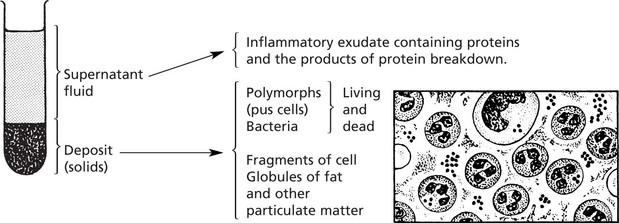

Resolution of lobar pneumonia (bacterial inflammation of lung alveoli) is a good example:

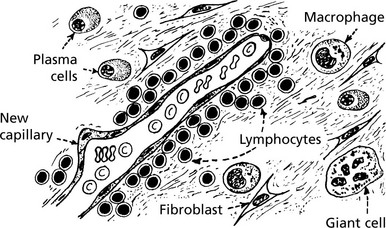

Organisation and Fibrosis

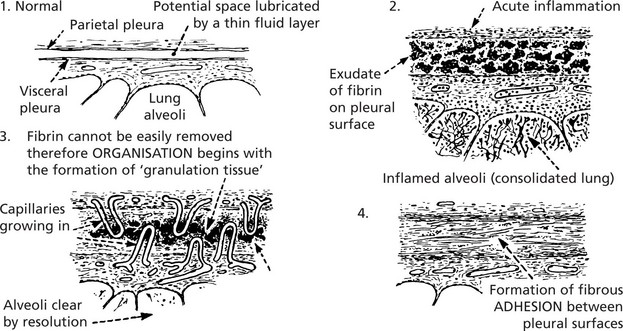

A good example of organisation following acute inflammation is seen in the pleura overlying pneumonia. The inflammation of the lung tissue proper usually resolves completely (p.264); in contrast the pleural exudate is not easily removed and organisation takes place.

Other good examples of organisation are seen after infarction (see p.166).

Chronic Inflammation

Chronic Inflammation may (a) follow acute inflammation if the causal agent is not removed: or (b) be ‘primary’, i.e. there is no pre-existing acute stage.

Common causes of ‘primary’ chronic inflammation include:

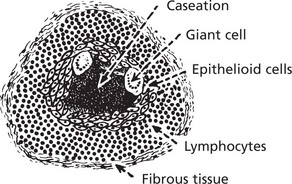

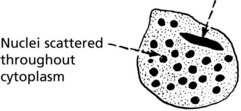

Granulomatous Inflammation

This is the term given to forms of chronic inflammation in which modified macrophages (epithelioid cells) accumulate in small clusters surrounded by lymphocytes. The small clusters are called granulomas. The basic lesion in tuberculosis is a good example.

Similar granulomas are seen in:

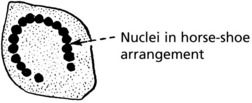

The Langhans’ giant cell – seen in chronic granulomata, e.g. tuberculosis and sarcoidosis.

The foreign body giant cell – seen in association with particulate insoluble material.

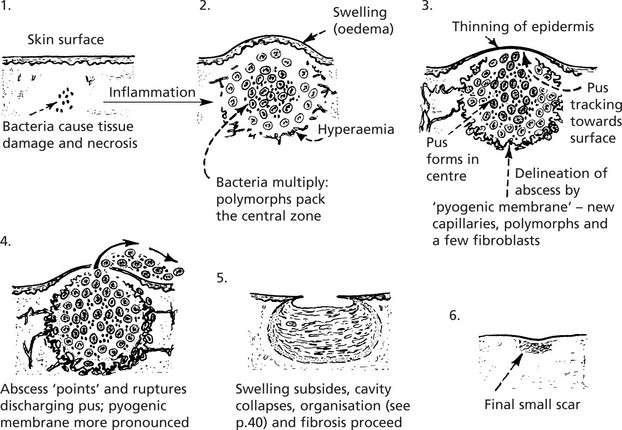

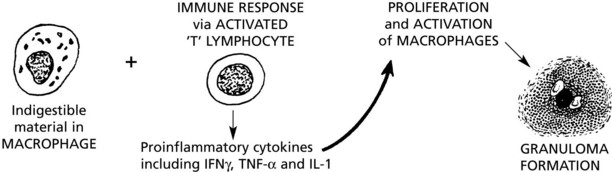

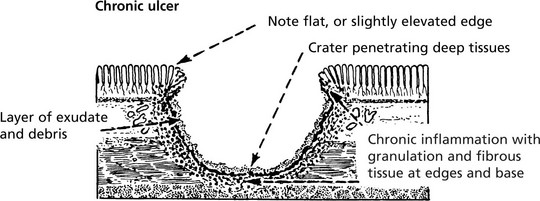

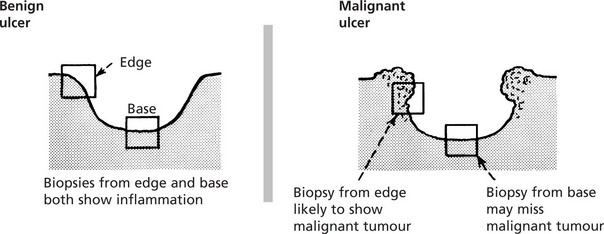

Ulceration – Benign

ULCERATION is a complication of many disease processes.

The most common sites are the alimentary tract and the skin.

Ulcers are divided into two main groups: 1. benign (inflammatory) and 2. malignant (cancerous).

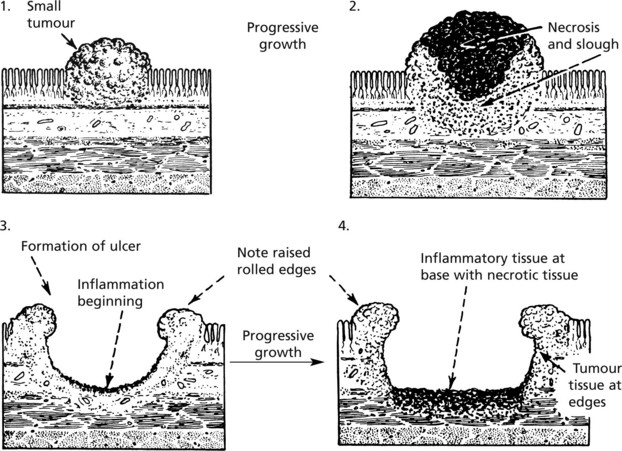

Ulceration – Malignant

Inflammation – Anatomical Varieties

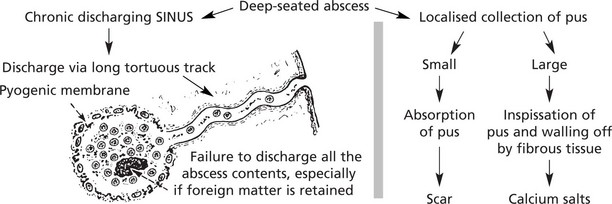

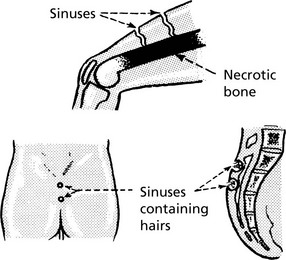

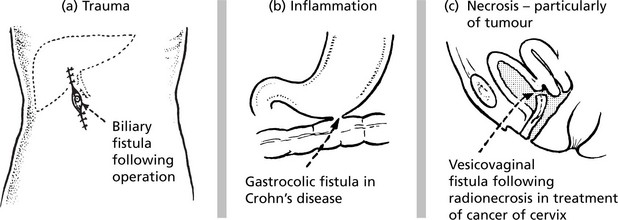

Sinus

A sinus is a tract lined usually by granulation tissue leading from a chronically inflamed cavity to a surface. In many cases the cause is the continuing presence of ‘foreign’ or necrotic material.