Infertility

Both partners should be seen and investigated together, as infertility may result from male or female factors and is often associated with a combination of both. At the completion of all investigations, about one quarter will be given a diagnosis of ‘unexplained infertility’. Long-term follow-up studies of couples with unexplained infertility have shown that 30–40% will conceive over a 7-year period after investigation. Many ‘unexplained’ cases involve women over age 35 years who may later be shown to have a poor response to ovarian stimulation and oocyte abnormalities if in vitro fertilization (IVF) is performed. Age, particularly female age, undoubtedly affects fertility. IVF success rates fall sharply for women age 35 or older (Table 17.1), and natural fertility appears to decline slowly but irrevocably from the late 20s onwards. The effect of age on the male is less pronounced, but older men exhibit more sperm abnormalities and DNA fragmentation.

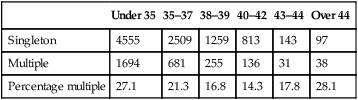

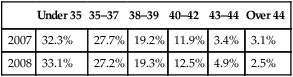

Table 17.1

Female age and IVF outcomes in the UK (2007 and 2008)

| Under 35 | 35–37 | 38–39 | 40–42 | 43–44 | Over 44 | |

| 2007 | 32.3% | 27.7% | 19.2% | 11.9% | 3.4% | 3.1% |

| 2008 | 33.1% | 27.2% | 19.3% | 12.5% | 4.9% | 2.5% |

(Data sourced from www.HFEA.gov.uk.)

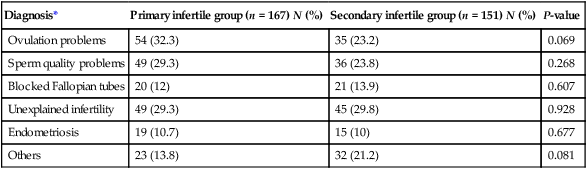

The relative incidence of causative factors will vary according to country and whether the problem is primary or secondary. Furthermore, in many couples there are multiple reasons for the infertility. Table 17.2 shows the pattern of causative factors of primary infertility in a Western population.

Table 17.2

| Diagnosis* | Primary infertile group (n = 167) N (%) | Secondary infertile group (n = 151) N (%) | P-value |

| Ovulation problems | 54 (32.3) | 35 (23.2) | 0.069 |

| Sperm quality problems | 49 (29.3) | 36 (23.8) | 0.268 |

| Blocked Fallopian tubes | 20 (12) | 21 (13.9) | 0.607 |

| Unexplained infertility | 49 (29.3) | 45 (29.8) | 0.928 |

| Endometriosis | 19 (10.7) | 15 (10) | 0.677 |

| Others | 23 (13.8) | 32 (21.2) | 0.081 |

*Women have reported more than one diagnosis.

Data derived from a Scottish general practice-based survey (Bhattacharya et al. 2009). Self-reported cause of infertility amongst women who reported a diagnosis (North East Scotland). The data reflect unsuccessful attempted conception for 12 months or longer and/or had sought medical help with conception.

History and examination

The history should include the following:

• Age, occupation and educational background of both partners.

• Number of years that conception has been attempted and the previous history of contraception.

• Previous conceptions of either partner in this or previous relationships.

• Details of any complications associated with previous pregnancies, deliveries and postpartum.

• Full gynaecological history including regularity, frequency and nature of menses, cervical smears, intermenstrual bleeding and vaginal discharge.

• Coital history, including frequency of intercourse, dyspareunia, post-coital bleeding, erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction

• History of sexually transmitted diseases and their treatment.

• A general medical history to include concurrent or previous serious illness or surgery, particularly in relation to appendicitis in the female or herniorrhaphy in the male; a history of undescended testes or of orchidopexy.

Examination of both partners should be considered, although examination of the male is unlikely to reveal anything of significance in the presence of a normal semen analysis, and of the woman may well be equally unremarkable if there is a normal high quality pelvic ultrasound. Azoospermic men should be examined for congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD) which is associated with cystic fibrosis mutations.

Female infertility

Disorders of ovulation

• Type I – hypogonadal hypogonadism resulting from failure of pulsatile gonadotrophin secretion from the pituitary. This relatively rare condition can be congenital (as in Kallman’s syndrome) or acquired, for example, after surgery or radiotherapy for a pituitary tumour. Serum concentrations of luteinizng hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and oestradiol are abnormally low/ undetectable and menses will be absent or very infrequent.

• Type II – normogonadotropic anovulation, most commonly caused by polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS; see Chapter 16). Serum concentrations of FSH will be normal and LH normal or raised. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) will be elevated and there may also be elevation of serum testosterone or free androgen index.

• Type III – hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, frequently described as ‘premature ovarian failure’ describes cessation of ovulation due to depletion of the ovarian follicle pool before age 40 years. Serum gonadotrophin concentrations will be greatly raised and AMH low/undetectable, with postmenopausal (low) concentrations of oestradiol.

• Type IV – hyperprolactinaemia, with elevated serum prolactin and low/normal serum FH and LH. Frequently due to a pituitary microadenoma although it is important to rule out a space occupying macroadenoma using pituitary MRI or CT.

Anovulation is usually associated with amenorrhoea or oligomenorrhoea. Alterations in the menstrual cycle are commonly associated with periods of stress and also with excessive weight gain or obesity, worsening the impact of PCOS on ovulation, or at the other extreme, with anorexia nervosa or excessive exercise leading to hypogonadal (type I) anovulation.

Tubal factors

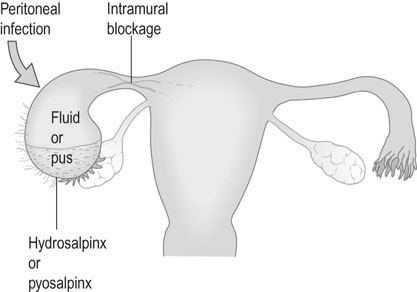

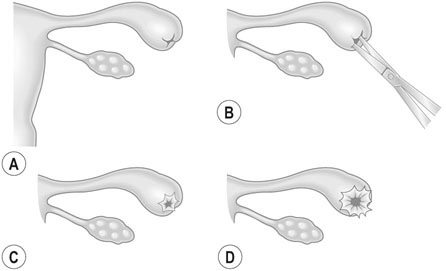

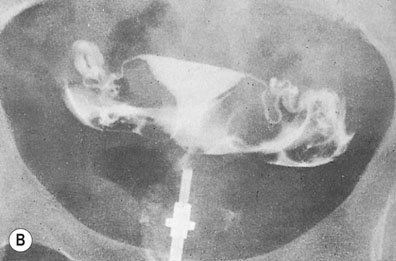

The Fallopian tube must first collect the ovum from its site of ovulation from the ruptured Graafian follicle and then transport the ovum to the ampullary segment, where fertilization occurs. The fertilized ovum must then be transported to the uterine cavity to arrive at the correct point in the menstrual cycle at which the endometrium becomes receptive to implantation (the ‘implantation window’). Tubal factors account for about 10–30% of cases of infertility: this figure varies considerably according to the population involved. Occasionally, congenital anomalies occur but the commonest cause of tubal damage is infection. Infection may cause occlusion of the fimbrial end of the tube, with the collection of fluid (hydrosalpinx) or pus (pyosalpinx) within the tubal lumen (Fig. 17.1).

Investigation of infertility

Investigation of the female partner

Investigation of tubal patency

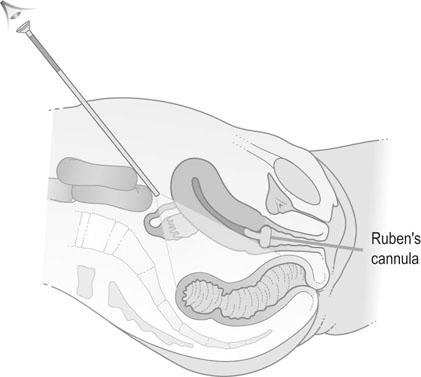

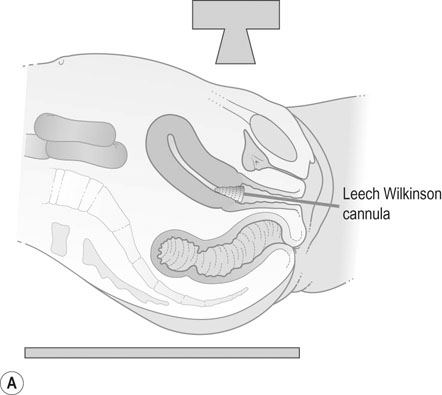

Hysterosalpingography

A radio-opaque contrast medium is injected into the uterine cavity and Fallopian tubes. General anaesthesia is unnecessary. The contrast medium outlines the uterine cavity and will demonstrate any filling defects. It will also show whether there is evidence of tubal obstruction and the site of the obstruction (Fig. 17.2). HSG should be performed within the first 10 days of the menstrual cycle to avoid inadvertent irradiation of a newly fertilized embryo. Women should be screened for C. trachomatis infection or given appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis before HSG in order to reduce the risk of reactivation of infection leading to pelvic abscess formation.

Laparoscopy and dye insufflation

Laparoscopy enables direct visualization of the pelvic organs and allows assessment of pelvic pathologies such as endometriosis or adhesions. Methylene blue is injected through the cervix in order to test tubal patency. Laparoscopy can be combined with hysteroscopy to assess the uterine cavity. A ‘see-and-treat’ policy allows for rapid surgical treatment of minor degrees of endometriosis or adhesions, although surgery that may result in damage to pelvic structures is better left to another occasion to allow full discussion of the implications of surgery to take place with the patient and her partner. Laparoscopy almost invariably requires general anaesthesia and there are small but significant risks of damage to pelvic structures including bowel, bladder and ureter at laparoscopy, so less invasive methods are preferred as first line investigations unless there is a specific indication, such as a history of pelvic inflammatory disease or appendicitis with peritonitis (Fig. 17.3).

Investigation of the male partner

The most useful investigation of the male partner is by semen analysis (Box 17.1). Semen should be collected by masturbation into a sterile container after 3 days abstinence and examined within 2 hours of collection. The sample is best collected in a private facility adjacent to the andrology laboratory to avoid cooling during transportation and allow accurate identification of the male partner.

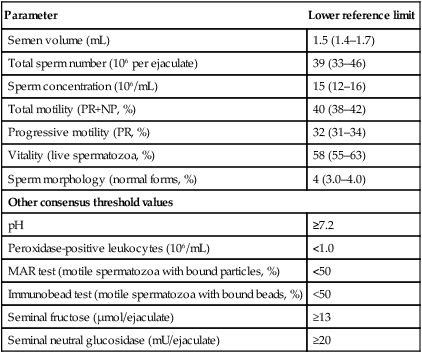

The recently revised lower reference limits and 95% confidence intervals for sperm parameters (WHO 2010) are given in Table 17.3.

Table 17.3

Lower reference limits (5th centiles and their 95% confidence intervals) for semen characteristics

| Parameter | Lower reference limit |

| Semen volume (mL) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) |

| Total sperm number (106 per ejaculate) | 39 (33–46) |

| Sperm concentration (106/mL) | 15 (12–16) |

| Total motility (PR+NP, %) | 40 (38–42) |

| Progressive motility (PR, %) | 32 (31–34) |

| Vitality (live spermatozoa, %) | 58 (55–63) |

| Sperm morphology (normal forms, %) | 4 (3.0–4.0) |

| Other consensus threshold values | |

| pH | ≥7.2 |

| Peroxidase-positive leukocytes (106/mL) | <1.0 |

| MAR test (motile spermatozoa with bound particles, %) | <50 |

| Immunobead test (motile spermatozoa with bound beads, %) | <50 |

| Seminal fructose (µmol/ejaculate) | ≥13 |

| Seminal neutral glucosidase (mU/ejaculate) | ≥20 |

(Data from Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, et al (2010) World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Human Reproduction Update 16:231–245.)

The major features of the semen analysis are:

• Volume: 80% of fertile males ejaculate between 1 mL and 4 mL of semen. Low volumes may indicate androgen deficiency and high volumes abnormal accessory gland function.

• Sperm concentration: The absence of all sperm (azoospermia) indicates sterility, although sperm may well be recoverable by percutaneous epididymal aspiration (PESA) or testicular aspiration (TESA) or testicular biopsy. The lower limit of normality is between 15 million and 20 million sperm/mL, but the findings should not be accepted on a single sample as there is significant fluctuation from day to day. Abnormally high values, in excess of 200 million sperm/mL, may be associated with subfertility.

• A normal analysis should show good motility in 60% of sperm within 1 hour of collection. The characteristic of forward progression is equally important. The World Health Organization grades sperm motility according to the following criteria:

grade 1 – rapid and linear progressive motility

grade 1 – rapid and linear progressive motility

grade 2 – slow or sluggish linear or non-linear motility

grade 2 – slow or sluggish linear or non-linear motility

• Sperm morphology shows great variability even in normal fertile males, and is less predictive of subfertility than count or motility. It is important to look for leukocytes as they may indicate the presence of infection. If pus cells are present, the semen should be cultured for bacteriological growth.

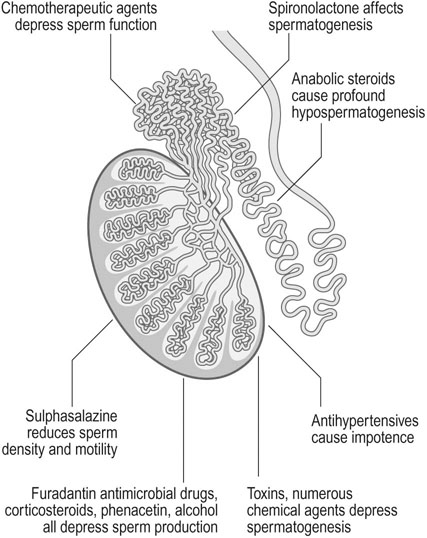

Spermatogenesis and sperm function may be affected by a wide range of toxins and therapeutic agents. Various toxins and drugs may act on the seminiferous tubules and the epididymis to inhibit spermatogenesis. Chemotherapeutic agents, particularly alkylating agents, depress sperm function and sulphasalazine, frequently used to treat Crohn’s disease, reduces sperm motility and density. Patients who are prescribed chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy should be offered sperm cryopreservation before treatment to allow them to start a family later in life once their disease has been successfully treated (Fig. 17.4).

Treatment of female subfertility

Tubal pathology

Salpingolysis to release peritubal adhesions still has a place if the fimbrial ends of the tubes are well preserved. However, it is important not to lose too much time if the woman is over 30 years of age. At times the blocked tubal end can be opened, i.e. salpingostomy (Fig. 17.5). There is an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy after all forms of tubal surgery.

In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer

The most frequent cause of obstetric and paediatric problems in offspring from IVF is the result of multiple pregnancy leading to premature birth. Transfer of two, three or more embryos in a single IVF cycle was commonplace in the early days of ART, but many countries, led by those in Scandinavia, have adopted a policy of single embryo transfer (SET) in the majority of IVF cycles. Multiple pregnancy rates remain at approximately 20% in UK, but are falling steadily (Table 17.4). Improved success rates from transfer of frozen embryos after cryopreservation using vitrification have made single embryo transfer a more attractive option to couples, since their chances of a live birth after sequential transfer of one fresh then one frozen embryo are equivalent to those seen after transfer of two fresh embryos, but without the risk of multiple pregnancy. The higher percentage of multiple pregnancies seen in the older patient groups reflects the lower overall chances of pregnancy, leading patients and practitioners to resort to desperate measures in order to try and achieve a pregnancy.

Table 17.4

Multiple pregnancy rates after IVF/ICSI – HFEA data

| Under 35 | 35–37 | 38–39 | 40–42 | 43–44 | Over 44 | |

| Singleton | 4555 | 2509 | 1259 | 813 | 143 | 97 |

| Multiple | 1694 | 681 | 255 | 136 | 31 | 38 |

| Percentage multiple | 27.1 | 21.3 | 16.8 | 14.3 | 17.8 | 28.1 |