Chapter 21 Infertility

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to conceive after 1 year of trying, differs from sterility, as many couples are able to conceive after a 1-year period. Sterility is the total inability to produce offspring; that is, the inability to conceive (female sterility) or to induce conception (male sterility),1 summarised in Table 21.1. Sterility is estimated to occur in 1% of cases. In about 80% of couples, the cause of infertility can be found.2 Infertility affects 10–15% of couples, 35% of which is attributed to female infertility and 30% to male infertility.3 This figure is now as high as 1 in 6 couples suffering infertility in New South Wales (Australia).4 It is essential infertile couples are investigated thoroughly to exclude reversible organic causes such as infections requiring antibiotics, or polyps requiring surgery.

| Origin of sterility | Cause |

|---|---|

| No eggs | Due to: |

(Source: adapted from Jansen R, 1998 Getting Pregnant. Allen and Unwin, Sydney)

Causes of infertility

Females

The following factors contribute to female infertility

General CM use

Complementary medicine use amongst infertile couples is common. In an Australian study of 100 women at a fertility clinic, 66% were using complementary medicines alongside prescribed medication, namely multivitamins, mineral and herbal supplements.5

Age as a risk factor

The risk of infertility in women and men increases with age and this is becoming a bigger problem as more women choose to delay childbearing. Infertility increased from 8% amongst women aged 19–26 and up to 18% in those aged 35–39 according to a European survey.6 Male age was significant after 30 years of age with estimated incidence of infertility of 18–28% between the ages of 35–40 years. The authors concluded that whilst older couples may have increased infertility, they may conceive if they keep trying for an additional year.

In a more recent study in the UK, data from a total of 7172 women at a fertility clinic, found there was an association between female age and the cause of female infertility and more women over 35 had unexplained infertility.7

Ovarian and uterine disorders

Other disorders include endometriosis plus ovarian causes of infertility including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which is commonly linked with autoimmune thyroid disorders.9

Nutrient deficiencies as risk factors

Deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals can contribute to infertility by affecting sperm count and motility in men, and hormonal processes in women.

Males

Antioxidants

It has been reported that in approximately 25% of couples, infertility can be attributed to decreased semen quality. In a recent convenience sample of healthy non-smoking men from a non-clinical setting, it was concluded that higher antioxidant intake was associated with higher sperm numbers and motility.10

Also, antioxidant deficits in males can lead to a decline in sperm motility. Spermatozoa cell membranes contain high concentrations of fatty acids, which are highly susceptible to oxidative damage. Adequate levels of antioxidants are required in order to maintain healthy cell membranes.11

Selenium

Selenium is an important nutrient for male fertility. Two of the proteins found to be structurally important in sperm require adequate levels of selenium.12 Deficiency is associated with decreased sperm motility and increased abnormal sperm.13

Females

Folate

An early study has suggested that blood folate level recovery in women following a normal pregnancy delivery and 1 year of breastfeeding may require supplementation with a multivitamin in order to re-establish blood folate levels before further conceiving.15 Folic acid deficiency can play a role in ovulatory infertility.16 Women trying to conceive within this 2-year period of folate replenishment may continue to experience difficulty with conception. Deficiency may also be caused by digestive disorders such as celiac disease.

Vitamin B2

Insufficient levels of vitamin B2 can lead to altered levels of oestrogen and progesterone, often causing irregular menstruation. Treatment of menstrual problems, such as irregular periods, PMT and general menstrual difficulties, often results in a correction of infertility issues also.17

Zinc

The effect of zinc deficiency on female fertility has not been extensively studied, however animal trials have linked low zinc levels with impaired ovulation and an increased amount of deteriorated ovocytes.19 Zinc supplementation can be beneficial for women experiencing fertility problems however an excessive presence of zinc also appears to be detrimental.20

General signs

Hormonal signals and Billings Ovulation Method (BOM)

A trial conducted by the World Health Organization in 5 different countries demonstrated up to 97% of women had an excellent or good interpretation of the BOM. However, couples should be encouraged not to use this method alone to assist conception. Similarly, the BOM can be used to help prevent conception as a natural method of contraception and if used correctly, can achieve a failure rate as low as 0.5–1.0% with accurate teaching and vigilant implementation.21, 22 However, higher reported failure rates, up to 3%, have been documented worldwide and occurred due to factors such as inadequate teaching, poor compliance and poor understanding of the BOM.23, 24, 25

Urinary ovulation predictors can be useful in identifying urinary LH surges at the time of ovulation, but requires the woman to estimate the timing of the ovulation and a LH surge is not necessarily followed up with an ovulation, as commonly occurs in PCOS and in luteinised unruptured follicle where some LH is released by the follicle but not enough to cause an ovulation. This method can be expensive for couples wanting to identify time of ovulation.

Scent of a woman

Interestingly studies indicate that the scent of a woman may provide a clue as to when she is ovulating and alert men to her current state of fertility. A study demonstrated that men could detect differences in body odour in women correlating to different stages of their menstrual cycle.26 Women menstruating were rated as the most intense and least attractive odour; whilst during the most fertile period they were rated by men as least intense smelling and the most attractive.

Lifestyle and diet

Lifestyle factors play an important part in successful fertility outcomes.27

A recent study has reported that couples who succeed in becoming fertile, especially those diagnosed with unexplained infertility, do so by adhering to lifestyle changes.28 Only those couples who sought information to help them conceive found the experience empowering.

Females

A cohort of 17 544 women monitored over an 8-year period found that women who adhered to a healthy lifestyle and fertility diet pattern were associated with a lower risk of ovulatory infertility disorder.29 This risk was reduced to 69% for women in the highest quintile group compared to those in the lowest quintile for adherence to the fertility diet pattern in healthy women. Furthermore, women’s age (older than 35 years of age), parity and body weight (Body Mass Index ≥ 25) were inversely associated with infertility.

The following lifestyle factors were protective towards infertility for women:

Mind–body medicine

Psychological factors

The therapeutic dilemma is how to use psychotherapy.30 Recently it was reported that medical and psychosexual therapies are not 2 distinct therapeutic entities to be used in different clinical settings. They are, however, 2 important tools to be simultaneously considered (as well as often simultaneously employed) to fully rescue the sexual satisfaction of the couple that is trying to conceive.

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) can be quite a stressful experience for many couples. Women who undergo IVF are more likely to have parenting difficulties and be admitted into a special unit for postnatal mood disturbance or infant sleeping disorder compared with women conceiving naturally.31 Couples undergoing IVF require additional support.

Support groups

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) was conducted to assess the benefits of a web-based education and support program for women with infertility and assessed for psychological outcomes such as infertility distress, infertility self-efficacy, decisional conflict, marital cohesion and coping style.32 At 4-weeks follow-up women exposed to the online program were observed to significantly improve in the area of social concerns related to infertility distress, and felt better informed about a challenging medical decision and experienced less global stress, sexual concerns, distress related to child-free living, increased infertility self-efficacy and decision-making clarity. Those women who spent more time online (>60 minutes) gained more psychological benefits.32

Stress reduction and/or meditation

Relaxation therapy

In a study measuring the effects of stress reduction on fertility, 54 women were enrolled in a behavioural treatment program and taught a relaxation response technique over 10 weeks. The women were instructed to utilise this practice twice daily for 20 minutes at home. At the end of the trial the women were reported as experiencing significantly less stress, depression and fatigue. Within months of completion of the study, 34% of the women became pregnant — a figure much higher than what is expected in women undergoing typical infertility treatment.33

Sexual activity

Infrequent or lack of sexual activity and difficulties with sex, such as erectile dysfunction in males, can interfere with fertility. Lifestyle factors such as overwork, exhaustion and night-shift can all impact on the frequency of sex and the chances of conception. Erectile dysfunction is a common problem in men over 60 years of age. Researchers in Finland found in over 1000 middle-aged men, that those who had infrequent intercourse (less than once weekly) were more likely to experience sexual dysfunction compared with men who had sex weekly.35 Stress and fatigue is a large contributor to lack of sexual activity.

Sleep

Shiftwork is associated with menstrual irregularities, reproductive disturbances, risk of adverse pregnancy outcome and sleep disturbances in women. A study of 68 nurses, aged less than 40 years, evaluated sleep, menstrual function, and pregnancy outcome and found 53% of the women noted menstrual changes when working shiftwork; menstrual irregularities which may impact on fertility.36

Sunshine

A number of animal studies have demonstrated vitamin D deficiency can cause infertility.37 Vitamin D is an important factor in the biosynthesis of both female and male gonads. No reliable human data are available yet to recommend vitamin D for infertility. Nevertheless, in view of the multiple health benefits of vitamin D from safe sun exposure, if blood levels are reduced then vitamin D supplementation should be advised in order to improve overall wellbeing.

Environment

Smoking

Smoking is well documented as contributing to problems with fertility in both men and women.38 Smoking reduces fertility in women by having a direct detrimental effect on the uterus, on the oocytes and embryos by increasing the zona pellucida thickness.39 Of interest, in a study of women who received donated eggs through an IVF program, those that smoked or had a history of smoking did not affect pregnancy outcome.40 Nevertheless, it is still advisable to instruct women to avoid smoking due to harmful effects on the fetus.

Infertile men who smoke have higher levels of seminal oxidative stress and sperm DNA damage41 and lower levels of antioxidant levels in the seminal fluid.42 Smoking was associated with a 48% increase in seminal leukocyte concentrations and a 107% increase in seminal oxidative stress compared with infertile non-smokers, suggesting men who smoke should quit.

Smoking increases the risk of impotence and erectile dysfunction in men who smoke or have a past history of smoking compared with those who have never smoked.43

External heat

Men should avoid high scrotal temperatures such as the use of hot tubs, long hours of sitting, and tight clothing as heat can inversely impact on sperm quality and count.44 Men who drove for more than 2 hours a day recorded significant scrotal temperature rises by 1.7–2.2°C than that recorded while walking. This rise in scrotal temperature indicates a potential cause for male infertility in some professions; for example, taxi drivers and office workers.

Chemicals and toxins

Exposure to environmental toxins such as radiation, heavy metals and chemicals can cause oxidative stress and sperm DNA damage.45–48 Oxidative damage to DNA may also impact on female fertility.49

Increased industrialisation and use of agricultural chemicals in the 20th century has contributed to exposure of thousands of chemicals which has contributed to impaired fertility in both men and women.50

Males

Semen quality, concentration and counts have declined significantly in a number of countries implicating exogenous oestrogens, heavy metals and pesticides as causes.51, 52

A US study of males found that sperm concentration was inversely related to the number of maternal beef meals per week.53 Son’s of mothers who consumed more than 7 beef meals per week had lower sperm concentration by up to 24% than in men whose mothers ate less beef. No other meat intake, such as lamb, was associated with low sperm. Also sperm concentration was lowest in men who ate more beef.53

Heavy metals

Exposure to heavy metals, such as lead and mercury, can interfere with fertility processes in men. For example, mercury can decrease the ability of the sperm to penetrate the ova for fertilisation, and causes breakages in sperm DNA strands. In women, lead can contribute to infertility, as well as other reproductive disorders such as premature membrane rupture, pregnancy-related disorders and premature delivery.54, 55

Cadmium exposure has also been associated with altered concentrations of serum estradiol, FSH and testosterone, the latter can lead to a decrease in testicular size.19

A study assessing heavy metals in premenopausal women found an association between cadmium and endometriosis.56 The study concluded that further investigations in properly designed studies were needed.

Seasonal and regional variations in sperm quality

Researchers noted regional variation in sperm quality across European nations and higher levels of sperm concentration noted over the winter period compared to summer (summer about 70% of winter).57 For instance, Finnish men have higher sperm counts than in Danish men. Environmental exposures and lifestyle factors may be contributors to these regional differences.

Physical activity

Exercise

Exercise plays an important role in fertility. Obese women with PCOS who suffered anovulatory infertility demonstrated a significant improvement in menstrual cycles and fertility equally in a structured exercise training (SET) program and to dietary interventions.58 Both the frequency of menses and the ovulation rate were significantly higher in the SET group than in the dietary group but the increased cumulative pregnancy rate was not significant.

However, a study of women undergoing IVF found that regular exercise before IVF may negatively affect outcome, especially in women who exercised 4 or more hours per week.59

Nutritional influences

As stated earlier under lifestyle, the high fertility diet has been shown to promote fertility.29 It includes a lower intake of trans fat, greater intake of monounsaturated fat, lower intake of animal protein, greater vegetable protein intake, higher intake of high-fibre, low glycaemic carbohydrates, preference for high-fat dairy products, and higher non-haeme iron intake (found in fruits, vegetables, grains, eggs milk, meat).

Alcohol

Excessive alcohol consumption can cause hyperprolactinemia which is associated with female infertility.61 In males, a high intake of alcohol has been shown to have a negative effect on Leydig cells, and therefore possibly on testosterone production.62 This is specifically caused by the ethanol in alcohol, and the degree of damage depends on the length of exposure and quantity ingested.63

Of interest, some alcohol consumption (1–20 standard drinks per week) is associated with reduced incidence of erectile dysfunction by 25–30% compared with non-drinkers.64

Caffeine

Caffeine promotes dopamine production, and this in turn inhibits the production of prolactin, a deficiency or excess of which increases the risk of infertility in women. Consuming as little as 1 caffeinated drink per day is associated with a temporary reduction in conception.65, 66

Underweight or overweight

Excessive or insufficient body weight in women is associated with infertility. For conception, the ideal body fat percentage in women is between 20% and 25%. A body fat percentage below 17% can result in anovulation and, following correction of body fat ratio, it may take as long as 2 years before regular ovulation resumes.67

A study of about 4000 pregnant women recruited from antenatal clinics or hospitals at least at 20 weeks of gestation, found after adjustment for socio-demographic, biologic and lifestyle-related factors, for women smokers there was a strong association between obesity (BMI of > or = 30 kg/m2) and women whose BMI was <20 kg/m2 and delayed conception. Of interest, the same analysis conducted for women non-smokers showed no association. The authors concluded that women who are underweight or obese require a longer time to conceive if they also smoke.67 A recent study demonstrated obesity is a clear risk factor reducing chances of spontaneous conception in sub-fertile, ovulatory women.68

In men, obesity (BMI >30kg/m2) is associated with hypogonadism, and therefore with infertility.69 Studies have shown a correlation between increased BMI and decreased testosterone levels, sperm motility and sperm concentrations.70–74

Trans-fatty acids (TFA)

TFA such as those found in commercially baked and fried products (e.g. French fries, fish burgers, chicken nuggets, corn chips, pies, Danish rolls and doughnuts) is linked to increased risk of infertility. A prospective cohort study of over 18 000 women demonstrated that for every 2% increase in energy intake from TFAs, there was a significant increase in risk of ovulatory infertility by up to 73% compared with no TFA intake. The study reported75 that this association was similar to that seen with fat intake and insulin in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

Males

Soy consumption

Soy contains isoflavones which are known to have mild estrogenic activity. Men who consume high dietary soy theoretically may suffer reduced sperm concentration consequently impacting on their fertility. Over a 3-month period, men who consumed isoflavone-rich foods (the equivalent of 1 cup of soy milk or 1 serving of soy product every second day), had on average less sperm concentration of 41 million/millilitre than men who didn’t eat soy.76 This inverse association was more evident in overweight and obese men. Soy products did not impact other parameters of sperm quality such as motility, morphology, total sperm count or ejaculate volume.

Nutritional supplements

Antioxidants

Antioxidants may be of benefit in infertility although there is mixed debate about their potential role. 77, 78 The general weight of evidence is supportive of the use of antioxidants for infertility.

Males

Antioxidants

Male sperm membranes are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids and are sensitive to oxygen-induced damage mediated by lipid peroxidation and free radicals. Seminal plasma contains a rich source of antioxidants and mechanisms which are likely to quench the free radicals and protect against any likely damage to spermatozoa. Antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione, and coenzyme Q10 have some proven beneficial effects in treating male infertility.79 Men who took just 1 multivitamin daily during IVF program recorded a statistically significant improvement in viable pregnancy rate (38.5% of transferred embryos resulting in a viable fetus at 13 weeks gestation) compared to the control group (16% viable pregnancy) of taking a placebo.80

Supplementation with antioxidant vitamins C and E, selenium and coenzyme Q10 can prevent and reverse oxidative damage to sperm and therefore increase sperm motility and quality.81 Sperm improved with antioxidant supplements (1g vitamin C and 1g vitamin E daily) even in short periods of time given over a 2-month period.82 The percentage of DNA-fragmented spermatozoa was markedly reduced in the antioxidant treatment group after treatment compared with pre-treatment levels.

High diet and supplement in vitamin C is associated with higher sperm number; vitamin E intake improved motility and sperm count; beta-carotene improved sperm concentration and motility.83

Vitamin C

An open trial of infertile male patients with oligospermia received 1000mg of vitamin C twice daily for a maximum of 2 months. Results showed that the mean sperm count increased from 14 x 106 sperms/ml to an average of 33 x106 sperms/mL, the mean sperm motility increased significantly from 31% to 60%, and mean sperms with normal morphology increased significantly from 43% to 67%. This study demonstrated that vitamin C supplementation in infertile men improves semen quality.84

Vitamin B12

Infertility disorders arising from B12 deficiency can be treated with B12 supplementation. Oral vitamin B12 can also be used provided that the patient does not have pernicious anaemia, where sublingual or injections of B12 are required. It may be wise to supplement with B12 where decreased sperm count and motility are present, even if no symptoms of deficiency are obvious.85

Folate

Folate did not demonstrate any benefits on sperm quality.86 However high total folate intake in diet and as supplements may lower the risk of genetically abnormal sperm known as aneuploidy but not for other micronutrients (zinc, vitamin C, vitamin E and beta-carotene).87

Glutathione

Glutathione is also instrumental in the defence against oxidative stress in the spermatogenic epithelium. It has been shown to be particularly important in the treatment of oligozoospermia due to its antioxidant effect during spermiogenesis.88 Glutathione has to be supplemented intramuscularly as it is destroyed in the stomach.89 Further, glutathione levels cannot be increased to a clinically beneficial extent by orally ingesting a single dose of glutathione.90 That is glutathione is manufactured intracellularly from its precursor amino acids, glycine, glutamate and cystine.

Minerals

Selenium

Supplementation with selenium has been shown in some trials to increase sperm count and motility. A small study of infertile men supplemented daily by vitamin E (400mg) and selenium (225μg) or vitamin B (4.5gm/day) over 3 months demonstrated the vitamin E and selenium treatment group produced a significant improvement of sperm motility and sperm quality in comparison to the vitamin B group.91 However, an excessive presence of selenium can have the opposite effect.92

Zinc

Supplementation with zinc can increase fertility, particularly in oligospermic men.93 Combined 66mg zinc and 5mg folate supplements improved sperm concentration by 18% in men who were sub-fertile compared with those on placebo.94

Another study demonstrated zinc supplementation did not benefit sperm quality.84

Amino acids

Arginine

Arginine deficiency can contribute to low sperm count and motility, but can be reversed with supplementation.95

Carnitine

A recent systematic review has concluded that supplementation with carnitine increased both sperm count and motility.96 The administration of L-carnitine and/or L-acetyl carnitine may be effective in improving pregnancy rate and sperm kinetic features in patients affected by male infertility. However, it was also reported that the exact efficacy of carnitines on male infertility needs to be confirmed by further investigations.96

Patients with abacterial prostatovesiculoepididymitis (PVE) and elevated seminal and leukocyte concentrations and on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for 2 months were followed by treatment with carnitine for 2 months. Men demonstrated significant reduction in reactive oxygen species associated with increased sperm motility and viability.97

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

CoQ10 may play a role in male infertility by increasing sperm motility. An open, uncontrolled pilot study of infertile men with abnormal sperm motility resulted in a significant increase in sperm motility compared with baseline.98 Similarly an RCT has found that CoQ10 treatment improves sperm motility in men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia.99, 100

Female

Antioxidants

Use of antioxidants together with a good diet improves fertility in women.5 A Cochrane review of the studies also found that women given any type of vitamin(s) compared with controls were significantly less likely to develop pre-eclampsia and more likely to have a multiple pregnancy.102

Minerals

Iron

Relative iron deficiency is common in women in reproductive years. Taking iron supplements up to 40mgs or more can reduce risk of anovulatory infertility by up to 60% and improve chances of conception compared with women who did not take iron supplements.104 Potential side-effects of iron supplements need to be weighed against any decision to supplement women with iron.

Herbal medicine

Males

The herbs discussed below have been used in the treatment of male infertility but there is incomplete evidence regarding their use.5, 105

Tribulus terrestris

Preparations based on the saponin fraction of Tribulus terrestris are used for treatment of infertility and libido disorders in men and women.106 Tribulus terrestris may increase testosterone levels, sperm count and sperm morbility.105, 106

Pygeum africanum,107, 108, 109 Plantago ovata111 and Serenoa repens111 may also be useful in infertility remedies.

Korean red ginseng (KRG) (Panax ginseng)

A double-blind cross-over study of 45 patients randomised to KRG or placebo over a 2-month period demonstrated improved penile rigidity and erectile function, and better penetration maintenance and erection during sex in the treatment group compared with the placebo group.112

Panax ginseng may be useful for increased sperm production.108, 109

Panax ginseng and Siberian ginseng may be useful for sexual dysfunction.113, 114

Pycnogenol

A small French study with 19 sub-fertile men given 200mg of pycnogenol daily (orally) for 90 days resulted in significant improvement in capacitated sperm morphology and mannose receptor binding.115 The study concluded that the increase in morphologically and functionally normal sperm could allow couples diagnosed with teratozoospermia to forgo IVF and either experience improved natural fertility or undergo less invasive and less expensive fertility promoting procedures (such as intrauterine insemination).106

Japanese herbal medicine — sairei-to

The Japanese herbs called sairei-to (9g/day) significantly increased sperm concentration and motility, and the pulsatility index of the testicular artery in men with oligospermia in a trial period over 3 months.116

Females

Vitex agnus castus

A randomised double-blind control trial of a registered product called Mastodynon® containing Vitex agnus castus preparation demonstrated improved hormone balance, recurrence of menstruation in women with amenorrhoea and pregnancy outcome in women with fertility problems compared with a placebo group.119 In women with amenorrhoea or luteal insufficiency, pregnancy occurred in the Mastodynon group more than twice as often as in the placebo group with minimal adverse effects.

Maca (Lepidium meyenii)

A randomised double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over trial demonstrated that 3.5g/day of Maca reduced anxiety, depression and sexual dysfunction in post-menopausal women independent of estrogenic and androgenic activity when compared with placebo over a 12-week period.121 Another study found Maca to alleviate SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in women suffering aggression.122

It is advisable that women avoid herbs during conception and pregnancy.

Physical therapies

Acupuncture for females

Acupuncture, as an adjunctive treatment for infertility in women, has produced promising results. In trials involving IVF, women receiving adjunctive acupuncture had higher rates of pregnancy than those receiving conventional treatment.122, 123

A recent Cochrane review of 13 RCTs involving acupuncture and assisted conception found there is evidence that acupuncture does increase the live birth rate with IVF treatment when acupuncture is performed within 1 day of embryo transfer (ET) but not when it is performed 2–3 days after ET.124 There were no adverse effects from acupuncture.

Some studies demonstrated that acupuncture in the luteal phase doubled IVF pregnancy rates125 and acupuncture did not have any adverse outcomes.126

Conclusion

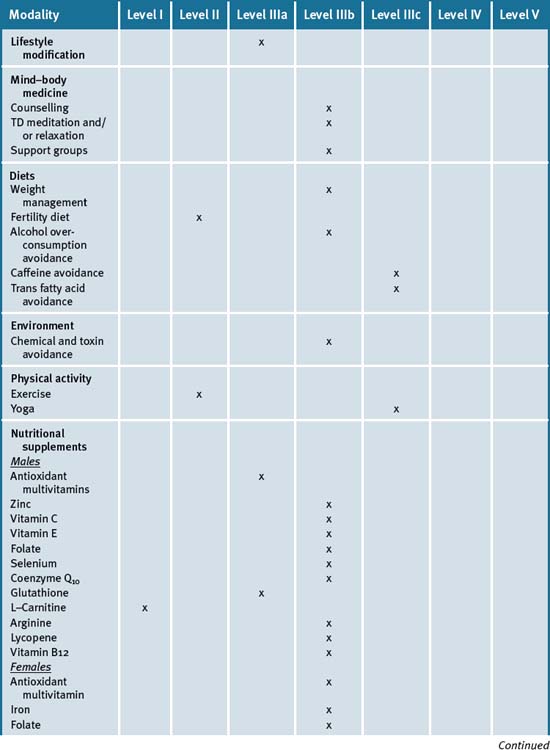

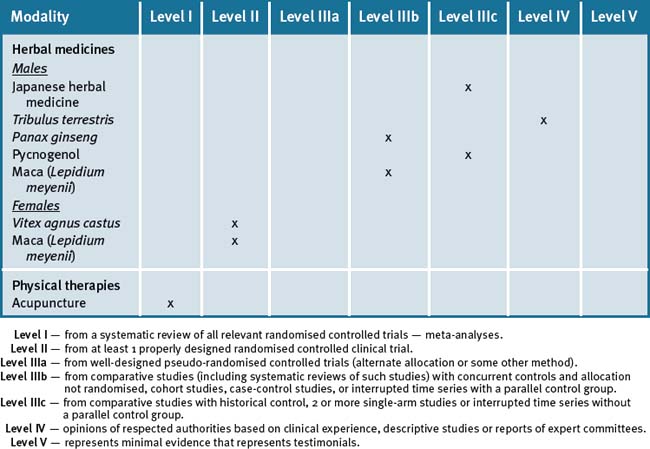

Table 21.2 summarises the level of evidence for some CAM therapies for infertility.

Clinical tips handout for patients — infertility

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

3 Mind–body medicine

Rest and stress management

4 Environment

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Females

Multivitamin

Males

Vitamin E (natural)

Vitamin B12

Zinc

Males

Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng)

1 http://cancerweb.ncl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/omd/?query = sterility (accessed January 2009).

2 Mosher W.D., Pratt W.F. Fecundity and infertility in the United States: incidence and trends. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:192-193.

3 Healy D.L., et al. Female infertility: causes and treatment. Lancet. 1994;343:1539-1544.

4 Laws P, Abeywardana S, Walker J, Sullivan EA.2007 Australian Mothers and Babies 2005 Perinatal Statistics Unit. No 20. Cat. No. PER 40 Sydney: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Perinatal Statistics Unit. http://www.npsu.unsw.edu.au/(accessed January 2009).

5 Stankiewicz M., Smith C., Alvino H., Norman R. The use of complementary medicine and therapies by patients attending a reproductive medicine unit in South Australia: a prospective survey. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(2):145-149.

6 Dunson D.B., Baird D.D., Colombo B. Increased infertility with age in men and women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;103(1):51-56.

7 Maheshwari A., Hamilton M., Bhattacharya S. Effect of female age on the diagnostic categories of infertility. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(3):538-542.

8 Hollowell J.G., et al. Serum TSH, T, and thyroid antibodies in the Unite States population (1988-1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocr Metab. 2002;87:489-499..

9 Janssen O.E., et al. High prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:363-369.

10 Eskenazi B., Kidd S.A., Marks A.R., et al. Antioxidant intake is associated with semen quality in healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):1006-1012.

11 Ebisch I.M., Thomas C.M., Peters W.H., et al. The importance of folate, zinc and antioxidants in the pathogenesis and prevention of subfertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(2):163-174.

12 Shrauzer G.N. Benefits of natural selenium. Anabolism. 1988;7(4):5.

13 Bedwal R., et al. Zinc, copper and selenium in reproduction. Experientia. 1994;50:626-640.

14 Boxmeer J.C., Smit M., Weber R.F., et al. Seminal plasma cobalamin significantly correlates with sperm concentration in men undergoing IVF or ICSI procedures. J Androl. 2007;28(4):521-527.

15 Bruinse H.W., van der Berg H., Haspels A.A. Maternal serum folacin levels during and after normal pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985;20(3):153-158.

16 Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Rosner B.A., Willett W.C. Use of multivitamins, intake of B vitamins and risk of ovulatory infertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(3):668-676.

17 Barron M.L. Light exposure, melatonin secretion, and menstrual cycle parameters: an integrative review. Biol Res Nurs. 2007;9(1):49-69.

18 Allen L.H. Multiple micronutrients in pregnancy and lactation: an overview. AJCN. 2005;81(5):1206S-1212S.

19 Favier A. The role of zinc in reproduction: Hormonal mechanisms. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1992;32:363-382.

20 Favier A. Current aspects about the role of zinc in nutrition. Rev Prat. 1993;43(2):146-151.

21 Weissmann M.C., et al. A trial of the Ovulation Method of family planning in Tonga. Lancet. 1972;2:813-816.

22 Qian S.Z., et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a natural fertility regulation program in China. The Woman of Today and Her Identity: Femininity, Fecundity and Procreation congress, Centre for Study and Research in the Natural Regulation of Fertility. Rome: Universita Cattolica del Sacro Cuore; 8 September 2000.

23 World Health Organisation. A prospective multicentre trial of the Ovulation Method of natural family planning. I: The teaching phase. Fertility and Sterility. 1981;36:152-158.

24 World Health Organisation. A prospective multicentre trial of the Ovulation Method of natural family planning. I: The effectiveness phase. Fertility and Sterility. 1981;36:591-598.

25 Ball M. A Prospective field trial of the ovulation method of avoiding conception. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Reprod Biol. 1976;6/2:63-66.

26 Havlícek Jan, Dvoráková Radka, Bartoš Ludek, Flegr Jaroslav. Non-Advertised does not Mean Concealed: Body Odour Changes across the Human Menstrual Cycle. Ethology. 2006;112:81-90.

27 House S.H. Nurturing the brain nutritionally and emotionally from before conception to late adolescence. Nutr Health. 2007;19(1–2):143-161.

28 Porter M., Bhattacharya S. Helping themselves to get pregnant: a qualitative longitudinal study on the information-seeking behaviour of infertile couples. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(3):567-572.

29 Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Rosner B.A., Walter C.W. Diet and Lifestyle in the Prevention of Ovulatory Disorder Fertility. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110:1050-1058.

30 Giommi R., Corona G., Maggi M. The therapeutic dilemma: how to use psychotherapy. Int J Androl. 2005;28(Suppl 2):81-85.

31 Fisher K., Hammarberg H. Baker. Assisted conception is a risk factor for postnatal mood disturbance and early parenting difficulties. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;84:426-430.

32 Cousineau T.M., et al. Online psychoeducational support for infertile women: a randomised controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(3):554-566.

33 Domar A.D., Seibel M.M., Benson H. The mind/body program for infertility: a new behavioral treatment approach for women with infertility. Fertil Steril. 1990;53(2):246-249.

34 Lovell-Smith H.D. Transcendental meditation and infertility. N Z Med J. 1985;98(789):922.

35 Koskimäki J., Shiri R., Tammela T., et al. Regular intercourse protects against erectile dysfunction: Tampere Ageing Male Urologic Study. American Journal of Medicine. 2008;21:592-596.

36 Labyak S., Lava S., Turek F., et al. Effects of shift-work on sleep and menstrual function in nurses. Health Care for Women International. 2002;23:703-714.

37 Kinuta K., Tanaka H., Moriwake T., et al. Vitamin D Is an Important Factor in Estrogen Biosynthesis of Both Female and Male Gonads. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1317-1324.

38 Tiboni G.M., Bucciarelli T., Giampietro F., et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on vitamin E, vitamin A, beta-carotene and lycopene concentrations in human pre-ovulatory follicular fluid. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17(3):389-393.

39 Shiloh H., Lahav Baratz S., Koifman M., et al. The impact of cigarette smoking on zona pellucida thickness of oocytes and embryos prior to transfer into the uterine cavity. Human Reproduction. January 2004;Vol. 19(No. 1):157-159.

40 Wright K.P., Trimarchi J.R., Allsworth J., Keefe D. The effect of female tobacco smoking on IVF outcomes. Human Reproduction. 2006;21(11):2930-2934. Online. Available: http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/21/11/2930 (accessed 19 June 2009)

41 Saleh R.A., Agarwal A., Sharma R.K., et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on levels of seminal oxidative stress in infertile men: a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(3):491-499.

42 Tiboni G.M., Bucciarelli T., Giampietro F., et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on vitamin E, vitamin A, beta-carotene and lycopene concentrations in human pre-ovulatory follicular fluid. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17(3):389-393.

43 Gades N.M., et al. Association between smoking and erectile dysfunction: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:346-351.

44 Bujan Louis, Daudin Myriam, Charlet Jean-Paul, Thonneau Patrick, Mieusset Roger. Increase in scrotal temperature in car drivers. Human Reproduction. 2000;15:1355-1357.

45 Appasamy M., et al. Relationship between male reproductive hormones, sperm DNA damage and markers of oxidative stress in infertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007 Feb;14(2):159-165.

46 Appasamy M, Muttukrishna S, Piszey AR, et al. Relationship between male reproductive hormones, sperm DNA damage and markers of oxidative stress in infertility. Online. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17298717?dopt = Abstract (accessed 19 June 2009).

47 Sanocka D., Kurpisz M. Reactive oxygen species and sperm cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:12.

48 Aitken R.J., Krausz C. Oxidative stress, DNA damage and the Y chromosome. Reproduction. 2001;122(4):497-506.

49 Agarwal A., Gupta S., Sharma R. Oxidative stress and its implications in female infertility – a clinician’s perspective. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;11(5):641-650.

50 Bhatt R.V. Environmental influence on reproductive health. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;70(1):69-75.

51 De Kretser D.M. Declining Sperm counts. Environmental Chemicals may be to blame. BM J. 1996;312:457-458.

52 Irvine S., Cawood E., Richardson D., Mac Donald E., Aitken J. Evidence of deteriorating semen quality in the United Kingdom: birth cohort study in 577 men in Scotland over 11 years. BMJ. 1996;312:467-471.

53 Swan1 S.H., Liu1 F., Overstreet J.W., Brazil C., Skakkebaek N.E. Semen quality of fertile US males in relation to their mothers’ beef consumption during pregnancy. Human Reproduction. 2007;Vol. 22(No.6):1497-1502. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem068

54 Winder C. Lead, reproduction and development. Neurotoxicology. 1993;14(2–3):303-317.

55 Triche E.W., Hossain N. Environmental factors implicated in the causation of adverse pregnancy outcome. Semin Perinatol. 2007;31(4):240-242.

56 Jackson L.W., Zullo M.D., Goldberg J.M. Hum Reprod. 2008 The association between heavy metals, endometriosis and uterine myomas among premenopausal women:. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 1999–2002;23(3):679-687.

57 Jørgensen N., Andersen A.G., Eustache F., et al. Regional differences in semen quality in Europe. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:1012-1019.

58 Palomba S., et al. Structured exercise training program versus hypocaloric hyperproteic diet in obese polycystic ovary syndrome patients with anovulatory infertility: a 24-week pilot study Hum Reprod. 2008;23(3):642-650.

59 Morris S.N., et al. Effects of Lifetime Exercise on the Outcome of In Vitro Fertilisation. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):938-945.

60 Khalsa H.K. Yoga: an adjunct to infertility treatment. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(Suppl 4):46-51.

61 Mendelson J.H. Alcohol effects on reproductive function in women. Psychiatry Letter. 1986;4(7):35-38.

62 Van Thiel D.H., et al. Ethanol, a Leydig cell toxin: evidence obtained in vivo and in vitro. Pharmacol Biochem behave. 1983;18(Suppl 1):317-323.

63 Anderson R.A.Jr., et al. Spontaneous recovery from ethanol induced male infertility. Alcohol. 1985;2(3):479-484.

64 Chew K.-K., Bremner A., Stuckey B., Earle C., Jamrozik K. Alcohol consumption and male erectile dysfunction: An unfounded reputation for risk? Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8, Jan 2009.

65 Casas M., et al. Dopaminergic mechanism for caffeine induced decrease in fertility? Letter. Lancet. 1989;i:731.

66 Homan G.F., Davies M., Norman R. The impact of lifestyle factors on reproductive performance in the general population and those undergoing infertility treatment: a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(3):209-223.

67 Bolúmar F., Olsen J., Rebagliato M., et al. Body mass index and delayed conception: a European Multicenter Study on Infertility and Subfecundity. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(11):1072-1079.

68 Van der Steeg J.W., Steures P., Eijkemans M.J., et al. Obesity affects spontaneous pregnancy chances in subfertile, ovulatory women. Hum Reprod. 2008 Feb;23(2):324-328.

69 Hedley, et al. Prevalance of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents and adults 1999–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2847-2850.

70 Hammoud A.O., et al. Obesity and male reproductive potential. J Androl. 2006;27:619-626.

71 Jensen T.K., et al. Body mass index in relation to semen quality and reproductive hormones among 1,558 Danish men. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:863-870.

72 Aggerholm A.S., et al. Is overweight a risk factor for reduced semen quality and altered serum sex hormone profile? Fertil Steril. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.011

73 Nguyen R.H., et al. Men’s body mass index and infertility. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2488-2493.

74 Hammoud AO et al. Male obesity and alteration in sperm parameters. Fertil Steril [doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.011].

75 Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Rosner B.A., et al. Dietary fatty acid intakes and the risk of ovulatory infertility. AJCN. 2007;85:231-237.

76 Chavarro J.E., Toth T.L., Sadio S.M., et al. Soy food and isoflavone intake in relation to semen quality parameters among men from an infertility clinic. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2584-2590.

77 Juan J., Tarı’n1, Brines Juan, Cano Antonio. Is antioxidant therapy a promising strategy to improve human reproduction? Antioxidants may protect against infertility. Human Reprod. 1998;13:1415-1424.

78 Martin-Du Pan R.C., et al. Is antioxidant therapy a promising strategy to improve human reproduction? Are antioxidants useful in the treatment of male infertility? Hum Reprod. 1998;13(11):2984-2985.

79 Sheweita S.A., Tilmisany A.M., Al-Sawaf H. Mechanisms of male infertility: role of antioxidants. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6(5):495-501.

80 Tremellen K., Miari G., Froiland D., Thompson J. A randomised control trial examining the effect of an antioxidant (Menevit) on pregnancy outcome during IVF-ICSI treatment. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007 Jun;47(3):216-221.

81 Greco Ermanno, Romano Stefania, Iacobelli Marcello, Ferrero Susanna, Baroni Elena, Giulia Minasi Maria, Ubaldi Filippo, Rienzi Laura, Tesarik Jan. ICSI in cases of sperm DNA damage: beneficial effect of oral antioxidant treatment. Human Reproduction. 2005;20(9):2590-2594.

82 Greco Ermanno, Iacobelli Marcello, Rienzi Laura, et al. Reduction of the Incidence of Sperm DNA Fragmentation by Oral Antioxidant Treatment. Journal of Andrology. 26, 2005.

83 Eskenazi1 B., Kidd S.A., Marks A.R., et al. Antioxidant intake is associated with semen quality in healthy men. Human Reproduction. 2005;20:1006-1012.

84 Akmal Mohammed, Qadri J.Q., Al-Waili Noori S., Thangal Shahiya, Haq Afrozul, Saloom Khelod Y. Improvement in human semen quality after oral supplementation of vitamin C. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2006;9(3):440-442.

85 Chen Q., Ng V., Mei J., Chia S.E. Comparison of seminal vitamin B12, folate, reactive oxygen species and various sperm parameters between fertile and infertile males. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2001;30(2):80-82.

86 Eskenazi B., Kidd S.A., Marks A.R., et al. Antioxidant intake is associated with semen quality in healthy men. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):1006-1012.

87 Young S.S., Eskenazi B., Marchetti F.M., et al. The association of folate, zinc and antioxidant intake with sperm aneuploidy in healthy non-smoking men. Human Reproduction. 2008;Vol. 23(No.5):1014-1022. doi:10.1093/humrep/den036. Advance Access publication on March 19, 2008

88 Lenzi A., Culasso F., Gandini L., et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial of glutathione therapy in male infertility. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1657-1662.

89 Anderson M.E. Glutathione: an overview of biosynthesis and modulation. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;111–112:1-14.

90 Witschi A., Reddy S., Stofer B., Lauterburg B.H. The systemic availability of oral glutathione. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43(6):667-669.

91 Keskes-Ammar L., Feki-Chakroun N., Rebai T., et al. Sperm oxidative stress and the effect of an oral vitamin E and selenium supplement on semen quality in infertile men. Arch Androl. 2003;49(2):83-94.

92 Hansen J.C., et al. Selenium and fertility in animals and man – a review. Acta Vet Scand. 1996;37(1):19-30.

93 Tikkiwal M., et al. Effect of zinc administration on seminal zinc and fertility of oligospermic males. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1987;31(1):30-34.

94 International Journal of Andrology, November 2005.

95 Lewis S.E., et al. Nitric oxide synthase and nitrite production in human spermatozoa: evidence that the endogenous nitric oxide is beneficial to sperm motility. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2(11):873-878.

96 Zhou X., Liu F., Zhai S. Effect of L-carnitine and/or L-acetyl-carnitine in nutrition treatment for male infertility: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16(Suppl 1):383-390.

97 Vicari E., La Vignera S., Calogero A.E. Antioxidant treatment with carnitines is effective in infertile patients with prostatovesiculoepididymitis and elevated seminal leukocyte concentrations after treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory compounds. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(6):1203-1208.

98 Balercia G., et al. Coenzyme q10 supplementation in infertile men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia: an open, uncontrolled pilot study. Fertility and Sterility. 2004;81:93-98.

99 Coenzyme Q10 treatment improves sperm motility. Nature Clinical Practice Urology. 2008;5:412. doi:10.1038/ncpuro1163

100 Balercia G., et al. Coenzyme q10 supplementation in infertile men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia: an open, uncontrolled pilot study. Fertility and Sterility. 2008;02:119.

101 Gupta N.P., Kumar R. Lycopene therapy in idiopathic male infertility–a preliminary report. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;34(3):369-372.

102 Rumbold A., Middleton P., Crowther C.A. Vitamin supplementation for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2005. Art. No.: CD004073. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004073.pub2

103 Forges T., Monnier-Barbarino P., Alberto J.M., et al. Impact of folate and homocysteine metabolism on human reproductive health. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(3):225-238.

104 Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Rossner B.A., Willett W.C. Iron intake and risk of ovulatory infertility. Obstetrics Gynecology. 2006;108:1145-1152.

105 Tempest H.G., Homa S.T., Routledge E.J., et al. Plants used in Chinese medicine for the treatment of male infertility possess antioxidant and anti-oestrogenic activity. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2008;54(4–5):185-195.

106 Rowland D.L., Tai W. A review of plant-derived and herbal approaches to the treatment of sexual dysfunctions. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(3):185-205.

107 Lucchetta G., Weill A., Becker N., et al. Reactivation from the prostatic gland in cases of reduced fertility. Urol Int. 1984;39:222-224.

108 Menchini-Fabris G.F., Giorgi P., Andreini F., et al. New perspectives of treatment of prostato-vesicular pathologies with Pygeum africanum. Arch Int Urol. 1988;60:313-322.

109 Clavert A., Cranz C., Riffaud J.P., et al. Effects of an extract of the bark of Pygeum africanum on prostatic secretions in the rat and man. Ann Urol. 1986;20:341-343.

110 Dhar M.K., Kaul S., Sareen S., Gill B.S. Plantago ovata: genetic diversity, cultivation, utilisation and chemistry. Plant Genetic Resources. 2005;3:252-263.

111 Bennett B.C., Hicklin J.R. Uses of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens, Arecaceae) in Florida. Economic botany. 1998;52:381-393.

112 Hong B., Ji Y.H., Hong J.H., et al. A double-blind crossover study evaluating the efficacy of Korean red ginseng in patients with erectile dysfunction: A preliminary report. The Journal of Urology. 2002;168:2070-2073.

113 Mkrtchyan A., Panosyan V., Panossian A., et al. A phase I clinical study of Andrographis paniculata fixed combination Kan Jang versus ginseng and valerian on the semen quality of healthy male subjects. Phytomedicine. 2005;12(6–7):403-409.

114 Salvati G., Genovesi G., Marcellini L., et al. Effects of Panax Ginseng C.A. Meyer saponins on male fertility. Panminerva Med. 1996;38(4):249-254.

115 Roseff S.J. Improvement in sperm quality and function with French maritime pine tree bark extract. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(10):821-824.

116 Suzuki M., Kurabayashi T., Yamamoto Y., et al. Effects of antioxidant treatment in oligozoospermic and asthenozoospermic men. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(9):707-712.

117 Gonzales G.F., et al. Effect of Lepidium meyenii (maca), a root with aphrodisiac and fertility-enhancing properties on serum reproductive hormone levels in adult healthy men. Journal of Endocrinology. 2003;176:163-168.

118 Zenico T., Cicero A.F.C., Valmorr L., Mercuriali M., Berocovish E. Subjective effect of maca on wellbeing and sexual performance in patients with mild erectile dysfunction. Andrologia. 2008;41:95-99.

119 Gerhard II, Patek A., Monga B., et al. Mastodynon(R) bei weiblicher Sterilität. Forsch Komplementarmed. 1998;5(6):272-278.

120 Brooks N.A., Wilcox G., Walkerk K., et al. Beneficial effects of Lepidium meyenii (maca) on psychological symptoms and measures of sexual dysfunction in menopausal women are not related to oestrogen of androgen content. Menopause: Journal of American Menopause Society. 2008;15(6):115-162.

121 Pording C., Fisher L., Papakostas G., et al. A double-blind randomised, pilot dose finding study of maca root (L. meyenii) for the management of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2008;14:182-191.

122 Stener-Victorin E., et al. A prospective randomised study of electro-acupuncture versus alfentanil as anaesthesia during oocyte aspiration in in-vitro fertilisation. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2480-2484.

123 Paulus W.E., et al. Influence of acupuncture on the pregnancy rate in patients who undergo assisted reproduction therapy. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:721-724.

124 Cheong Y.C. Hung Yu Ng E, Ledger WL. Acupuncture and assisted conception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2008. Art. No.: CD006920. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006920.pub2. Online. Available: http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab006920.html (accessed 19 June 2009)

125 Dieterle S., Ying G., Hatzmann W., et al. Effect of acupuncture on the outcome of in vitro fertilisation and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a randomised, prospective, controlled clinical study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(5):1347-1351.

126 Smith C., Coyle M., Norman R. Influence of acupuncture stimulation on pregnancy rates for women undergoing embryo transfer. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;85:1352-1358.